Edited and with an introductory essay byProf. Richard Taylor (English). Universityof Illinois Press, 1969. 382 pp. $1O.OO.

The subject of Mr. Taylor's book, Frank Pearce Sturm (1879-1942), was one of the more improbable minor figures in early twentieth-century literature. Indeed, he belonged to the literary world only tangentially, for he was at once a scientist, medical doctor, student of Eastern mysticism, Buddhist, editor of Baudelaire, literary critic, and poet. He is memorable to literary historians chiefly because he was a long-time friend of, and correspondent with, the major poet of our century, William Butler Yeats.

Much of one's admiration for Mr. Taylor's book is generated by an awareness of the skill with which the author avoids one of the common pitfalls of contemporary literary scholarship. Conceived under the gun of academic pressures to publish, exhaustive studies of minor figures who, like Sturm, clustered around our literary giants have become, unfortunately, standard scholarly fare. Trailing their blizzards of learned footnotes and extensive bibliographies of minutiae, such books usually make dreary reading. Their besetting sin is over-inclusiveness; as an eminent literary scholar once complained, "They tell me more about the subject than I want to know."

But not so with this book. By a deft balancing of his roles as biographer and editor, Mr. Taylor escapes the trap of over-assiduous scholarship. Wisely he does not attempt a full-scale biography; to have done so would have been to create a too massive pedestal for an uncomfortably small statue. After a concise biographical sketch the author turns editor and allows Sturm to speak for himself. He reproduces the Yeats-Sturm correspondence, excerpts from Sturm's diary, and Sturm's collected works (poetry and prose).'

A unique repository of information, this book deserves the attention of everyone seriously concerned with early twentiethcentury literature. The scholar will be particularly interested in Mr. Taylor's demonstration of the similarities between the imagery of Sturm's poetry and that in several of Yeats's major poems, and in the influence which Sturm may have exerted on Yeats's exegesis of his own mystical metaphysic in A Vision. The general reader may perhaps be more attracted by the excerpts from Sturm's diary. In a confessional vein, they reveal something of the spiritual history of a paradoxical, tormented human being, a Buddhist mystic who practiced medicine in industrial Lancashire but who would have been better fitted, by his own admission, to "a moonlit cell of a lonely monastery high up on Adam's Peak" in Ceylon.

Mr. Taylor's conclusion that Sturm's major contribution to literature lay in his editing Baudelaire surely cannot be disputed. In any event, it most emphatically does not lie in his poetry. A reading of Sturm's poems, indeed, convinces one anew of the ineluctable genius of Yeats. For although both poets share some common themes, even common images, although both strive to express their mystic insights, and although both demonstrate a few of the same "influences" (e.g., the Symbolistes), Yeats's poems sing on the golden bough or soar precisely balanced on the wings of intellect and passion. Sturm's often flutter ineffectively amid prettified fin de siècle cliches or flounder in the nets of versified prose. The long poems are particularly fragmented and opaque; nowhere does one encounter anything even approaching Yeats's architectonic sense. As Yeats wrote Sturm in 1918, in the longer works "you let your imagination drift on from image to image. The binding thread is often so weak that the beads before the end lie scattered on the ground. That is perhaps why I like you best in poems . . . where the short lines and the corresponding energy of rhythm holds all together." Yeats was, as usual, right.

Mr. Ross is author of The Georgian Revolt, 1910-1922, Professor of English, and Director of English Graduate Studies, Washington State University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

October 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe Transcending Great Issues

October 1969 -

Feature

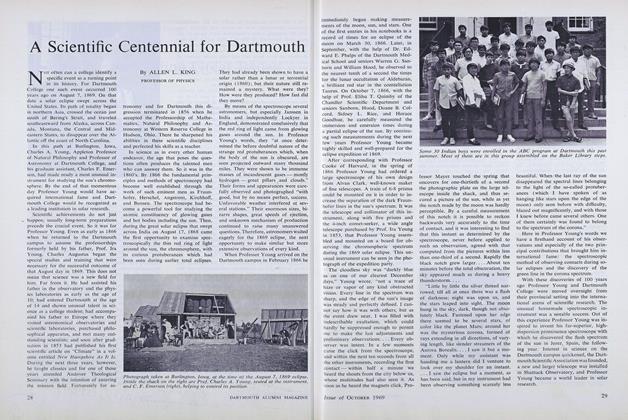

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

October 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureWhitewater Racing Gains New Status

October 1969 By JAY EVANS '49 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Draws Unusual Gifts

October 1969 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1969

ROBERT H. ROSS '38

-

Books

BooksTHE FOUR SEASONS OF SUCCESS.

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFacing the Great Issues

MARCH 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTelling Tales

APRIL 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksGalaxies

November 1979 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksValedictory

DECEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Notes

October 1947 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

OCTOBER 1967 -

Books

BooksOUTPOSTS OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL

April 1939 By Highly Recommended, Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksTHE TRANSPORTATION ACT OF 1958.

APRIL 1970 By MARTIN L. LINDAHL A.M. '40 -

Books

BooksOLD QUOTES AT HOME.

JANUARY 1968 By MAUDE FRENCH