PRESIDENT Dickey, faculty, members of the Class of 1955, parents and guests. We are meeting here today in these Commencement exercises to recognize the successful completion for seniors of four years at Dartmouth. During the past few days this recognition has taken many forms - we have celebrated with our families and our friends, we have talked and laughed and probably grinned a little at the congratulations we are not quite sure we deserve, we have made farewells and promises, and perhaps have paused to reflect and to wonder about the future. There has been an element of finality in all these forms of recognition, a finality which stems from the simple and sobering fact that we are at the end of sixteen years of formal education, a finality which is symbolized in the ceremony of the diploma.

But this element of finality has been accompanied by one of release and genesis, a growing awareness of the deeper meaning of that which we acknowledge today, our commencement. We have been told that we are being sent to the plate to take our initial swing at the ball of life, that this is the launching of the ship of ourselves, and we listen and understand without really knowing. Intellectually we accept the promises and responsibilities of the future, but emotionally we cannot. Until we have had to work for the money which pays for our food and housing, until we have admitted our need of the ones we love, until we have waited and worried while our wife gives birth to a child, we cannot fully understand the meaning of this beginning, this commencement. The capacity for compassion and sympathy which is at the core of every truly educated man can develop only from a long process of experience piled upon experience. The most we can expect from the past four years is to have taken our first confident strides along the path of this process.

And how are we to tell if this expectation has been fulfilled. It is not easy, for each man must determine his own criteria. Today I would like to suggest that one way in which the length of these strides can be measured is by the yardstick of the family. To many of us, this commencement symbolizes the realization of a fuller and richer relationship between the parent and the child, a realization which has grown from an involved, often painful, but thoroughly natural and healthy contrast in attitude and opinion. Just as we, looking back on the past four years, may have considered you, our parents, a barrier in the pathway of our development, I somehow suspect that when we ignored the speed-signs you placed along this pathway, you felt we were the ones increasing the tensions on the bonds between us. And yet it is only because of these tensions that a strength and maturity of understanding may have resulted.

Somehow the proud and lonely high school graduate who hastily kisses the air beside his mother's cheek in the fall of his freshman year grows away from his parents while in college. He may deny many of the intellectual, moral and religious teachings of his parents, and if he does not deny them, at least he doubts them. If he lives by the creed that it is impossible to know whether something is indispensable unless it has been dispensed with for a while, it is only because he is convinced of the truth of the creed. And don't think this is an easy process; this business of doubting, of chopping away at the foundations upon which one's life is constructed, is as perplexing and frustrating as it is healthy and edifying.

But if we have had the courage to stagger into the forest of intellectual examination here, we have at least subjected ourselves to the possibility of emerging more experienced, enthusiastic and responsible individuals. And whether or not the blazes we have discerned on the trees of insight are the same ones our parents predicted we would find here, our struggles have provided the source from which a true appreciation of family emanates.

Kahlil Gibran speaks as the prophet to the families of Orphalese:

Your children are not your children, They are the sons and daughters of life's longing for itself.

They come through you, but not from you, And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love, but not your thoughts.

For they have their own thoughts....

You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

Education is a mutual process between parent and child. If these four years have helped you, the parents, to love your children as they are, as products not solely of your own teaching, but of the teachings of others as well, then you have gained an understanding of the nature of education which may enrich and solidify your family. And if we, by observing ourselves as participants in this same process, have gained this same insight, then not only will our present family lives be on a more wholesome footing, but when in the future we send our own children away, we may have the intelligence and compassion to allow them what we have demanded for ourselves.

Commencement has a different meaning for every individual who participates in it. The thoughts I have expressed today have been limited to but one element of the educational process which these ceremonies conclude, but to me they are thoughts whose importance cannot be overestimated.

JERE R. DANIELL II '55

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

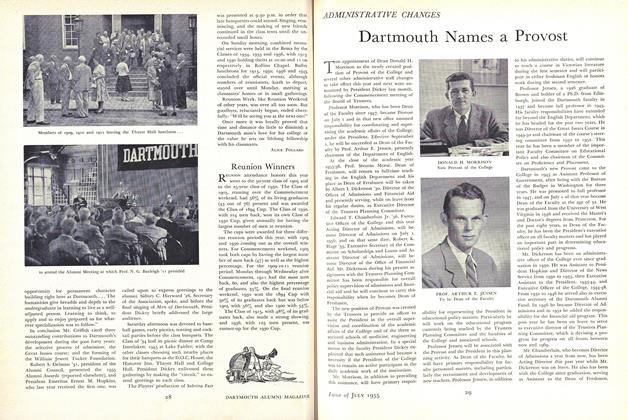

FeatureADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES

July 1955 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Tops $760,000

July 1955 -

Feature

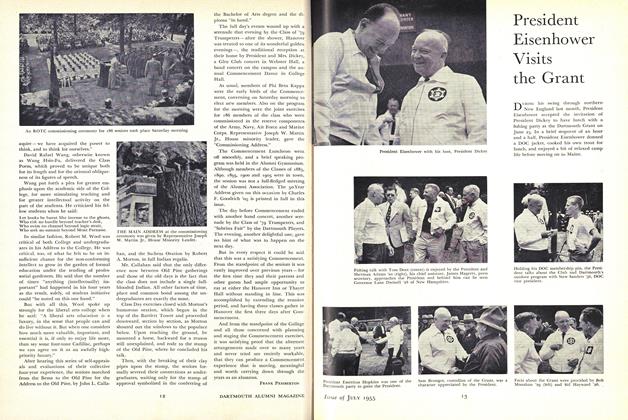

FeaturePresident Eisenhower Visits the Grant

July 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930's History-Making 25th

July 1955 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN '30 -

Article

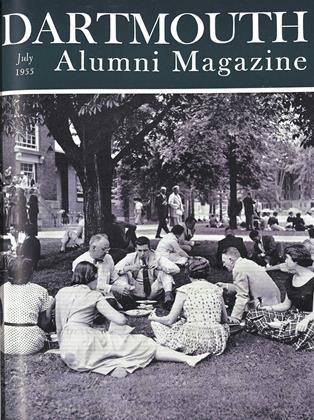

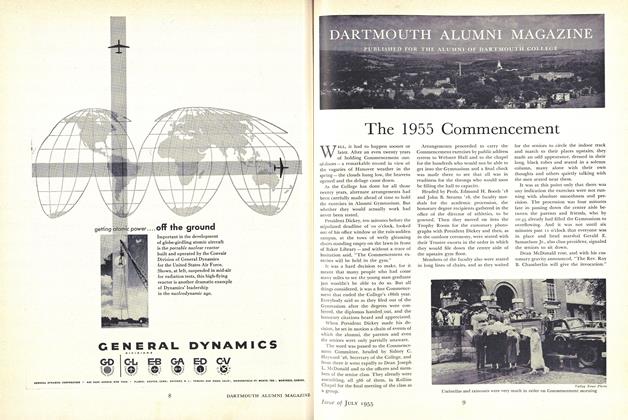

ArticleThe 1955 Commencement

July 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Class Notes

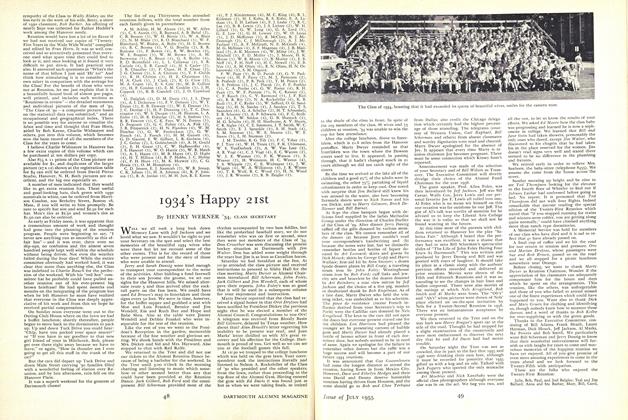

Class Notes1934's Happy 21 st

July 1955 By HENRY WERNER '34