of Alphonso Converse Stuart Dartmouth 1809

ILLINOIS was rough country in 1819, a part of the westward-moving frontier. Its towns were inhabited by sturdy and determined people; men from New England and New York, from New Jersey, Pennsylvania and the South; families that had packed their belongings into covered wagons and set off alone or in wagon trains to seek the opportunities of the West.

Belleville in the southwest portion of the state, fifteen miles from the Mississippi, was such a town. A settlement of log houses sheltering something under 300 souls, it was the seat of St. Clair County. Its life, like that of the other outpost villages, was simple, if not primitive, and seems generally to have been both peaceful and serene.

But on the eighth of February, 1819, Belleville, Illinois, must have been anything but peaceful and serene. Indeed, there would have been great clamor and activity as the town became electrified by the news that quickly spread through it the news that Timothy Bennett had just shot and killed Attorney Alphonso Stuart and under circumstances as incredible as one could conceive.

The dead man, Alphonso Converse Stuart, had been born in Claremont, New Hampshire, on March 13, 1785, the son of Jonas and Mary (Grimes) Stuart. He was graduated from Dartmouth with the Class of 1809, following which he entered the law. It has been reported that he was licensed to practice in Pennsylvania in 1812 and that he lived in Reading just prior to emigrating from the East.

He settled at Belleville in 1816 and is said to have been admitted to the Illinois bar during the following year. He was a married man, and he and his wife, Rachel, had three sons, the oldest of whom was not yet fourteen at the time of his father's death.

Stuart's trouble with Timothy Bennett, which was to end in such startling tragedy, had its origin in a seemingly trivial matter. Bennett owned a horse, a "breachy" animal, that repeatedly broke into Stuart's cornfield. This greatly angered the lawyer, who warned Bennett that unless he curbed its vagrant tendencies, he would shoot the beast.

Bennett, however, chose to disregard the warning and made no effort to restrain the horse, which, oblivious to the growing illwill being caused by its repeated visits, continued to break into the field. One day Lawyer Stuart determined to put up with it no longer. A gun was loaded with powder and coarse salt (one account says beans), and his hired man, whom he had induced into acting in the capacity of executioner, sallied forth to do the deed which sent the animal galloping for home, bleeding and smarting with pain.

The horse was a favorite with Bennett, and although the wound inflicted was slight, he became enraged over the incident and was "disposed to seek revenge."

"While in this frame of mind," records James Affleck, a citizen of Belleville at the time whose reminiscences contain what appears to be the most accurate account available, Bennett met with Jacob Short and Nathan Fike, "a pair of young Bacchanalians, who made their haunt, and hibernated, at Tannehill's tavern, which then occupied the southwest corner of the public square. . ."

(James Tannehill's tavern, one may properly deduce, was the center of some segment - albeit perhaps the more bibu- lous part - of Belleville's social life, and it figures prominently in the Stuart-Bennett melodrama. It has, in fact, been suggested of Attorney Stuart in connection with this establishment that "his practice was more frequent at Tannehill's bar than at that of Judge Reynolds." Although this statement may or may not have been founded in fact, it must in fairness be observed in the young lawyer's favor that none other than this same Judge John Reynolds in his Pioneer History of Illinois characterized him as "a fine classic scholar and a well-read lawyer," whose death "put an end to his usefulness and promise.")

"Short and Fike," continues Mr. Affleck's narrative, "thinking to have some sport out of the affair, advised Bennett to seek satisfaction from Stuart by challenging him to mortal combat. They told him that Stuart had grievously injured and insulted him, and that the only proper course for him to pursue was to challenge him to fight a duel. Bennett readily assented to this, and the challenge was sent.

"In the meantime Short and Fike saw Stuart and told him of their plan to have some sport out of Bennett, and they at once arranged for a sham duel. Short and Fike, who were to act as seconds, promised Stuart that the guns should be loaded with powder only."

It appears that everyone in Belleville, except Timothy Bennett himself, was soon aware that the forthcoming duel was to be a fraud and that Bennett was to be made the butt of the mockery that had been conjured up by the two seconds.

Undoubtedly exchanging winks and knowing glances, "The young men of the town teased and plagued Bennett a good deal...." They told him that when the time came he would "take the 'buck ague,' " implying that because of nervousness he would not be able to fire..

To the suggestion that he could not shoot with accuracy, Bennett on one occasion proved himself a marksman by loading his gun and blowing the head off a chicken in a nearby yard. But this, of course, must only have increased the great glee of his tormentors, who very likely could visualize Bennett's astonished countenance and the hilarious scene on the duelling ground when his deadly aim would be accompanied by nothing more than a loud noise and a puff of smoke.

ON February 8, the parties to the duel met at the courthouse, where the details were agreed upon. (The weapons - quite appropriate to the frontier - were to be rifles.) Then, with final arrangements made and suitable fortification for the ordeal having been provided by ample quantities of Tannehill's whiskey, the group repaired to the site selected for the contest, a vacant area outside of town, where there was but a scattering of trees.

The two men were placed about twenty-five paces apart and when both were ready the word "Fire" was cried. Hardly had it left the speaker's lips when the report from Bennett's gun was heard. But instead of this producing the burst of merriment and raillery that the spectators had expected to enjoy, to the great horror of all present Alphonso Stuart fell, face downward, mortally wounded in the region of the heart. He died instantly as he struck the ground.

Before, perhaps, anyone had recovered from the shock of this unexpected and grotesque turn of events, Fike, Stuart s second, -went to the body, turned it over in order to seize the dead man's gun, and fired it into the air. Thus, it was never known whether Stuart's rifle had also contained a ball or merely the harmless powder charge that had been agreed upon.

Under Illinois law a fatal result in a duel was murder and all the participants principals to the crime. The body of Alphonso Stuart, buried only a hundred yards from where it had fallen, gave mute but eloquent testimony that here clearly was a case within the meaning and intent of the law. Accordingly, Short, Tike, and Bennett were immediately arrested and placed in the Belleville jail to await a trial at which it might be determined which of them would be accorded the dubious distinction of being the object of the first legal execution in the State of Illinois.

The duel had taken place only two months after Illinois had been admitted to the Union, and the state appears to have had no established legal machinery in St. Clair County adequate to deal with the Stuart murder. Fortunately, however, the legislature was at the moment in session at Kaskaskia, and the necessary bills were enacted with dispatch. A special term of the circuit court was authorized, and the proper officials appointed.

Certainly there were many questions to be answered. It has been said that Alphonso Stuart had no intention of firing at all, thinking thereby to heighten still further the ludicrous effect of the farce. But why had Nathan Fike shown such anxiety to discharge the dead man's gun? Had it too been loaded with a rifle ball? (There were those who suspected "that the crack of the gun was that of one containing a ball.") If so, who had placed it there?

And who was responsible for loading Timothy Bennett's rifle with the bullet that had killed Attorney Stuart? Had Bennett, as some accounts have it, also been aware of the hoax? And had he through malice added the ball to the powder charge prior to going onto the field? Or, unaware of the joke, had he suspected the seconds, checked the chamber of his rifle, and added the ball, thinking that he was being tricked?

Or had Short and Fike conspired to bring about this end, and had one of them placed the deadly charge in Bennett's gun?

ON March 8, 1819, just a month from the day of the fatal "mock duel," the grand jury presented a bill of indictment against Bennett and the two seconds (the latter in the meantime had been released on bail), and the clerk issued a process directing Sheriff William A. Beaird to bring Bennett into court. The sheriff, however, was forced to reply: "The within named Timothy Bennett has made his escape by breaking the jail of St. Clair County; therefore, I cannot bring his body in the court as I am commanded."

The building that served as the Belleville jail was a log structure, and on the eve of the trial Bennett had gained his freedom by boring a series of holes in one of the logs and forcing it from its place. He fled Illinois, crossing the Mississippi, and disappeared into the wilds of the Arkansas Territory.

The escape caused a postponement of the proceedings, and it was not until the next term of the court in June that Short and Fike were brought to trial. With Timothy Bennett still at large, the case got under way. The two men pleaded 'not guilty' and were quickly acquitted, chiefly on the strength of the testimony of Rachael Tannehill.

A girl of nine or ten years, Rachael revealed that she had been looking out of an upper-story window in the Tannehill tavern when the group left for the duelling field. Bennett, she said, had come around the courthouse, at a distance of about seventy or eighty feet from where she watched, and had placed in the chamber of his rifle an object which she "construed to be a bullet."

With the seconds freed, authorities continued to seek apprehension of Bennett. Two years passed, throughout which time there stood a reward for his capture, before he was heard of again. It was then learned that the outlaw was in St. Genevieve, Missouri, just across the Mississippi, nearly 40 miles south of Belleville. He had communicated with his wife and planned to have her and their children join him. Also, he sent a team and wagon to carry the family to where he would meet them.

With this intelligence, a group of townsmen followed the wagon when it left town, and upon reaching the river they found Bennett awaiting its arrival. He was placed under arrest and brought back to answer for the crime with which he was charged.

On July 26, 1821, Bennett was indicted once more by the grand jury. With the speed that is supposedly characteristic of old-time frontier justice, the trial jury was impaneled, made its "patient investigation of the cause," returned its verdict and on July 28th the prisoner was sentenced "to be hanged by the neck until dead."

Little more than a month later, on Monday afternoon, September 3, 1821, all appeals for a stay of execution having been rejected, the sentence was carried out. Timothy Bennett was led to the gallows west of town, and there, protesting his innocence to the end, was hanged for the strange murder of Alphonso Converse Stuart, frontier lawyer and member of the Dartmouth Class of 1809.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Hopkins Center Concept

April 1956 -

Feature

FeatureELECTION-YEAR CONFERENCE

April 1956 By ROBERT H. GILE '56 -

Feature

FeatureA Tuckerman Tradition

April 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1956 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, JOHN W. MOXON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

April 1956 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Feature

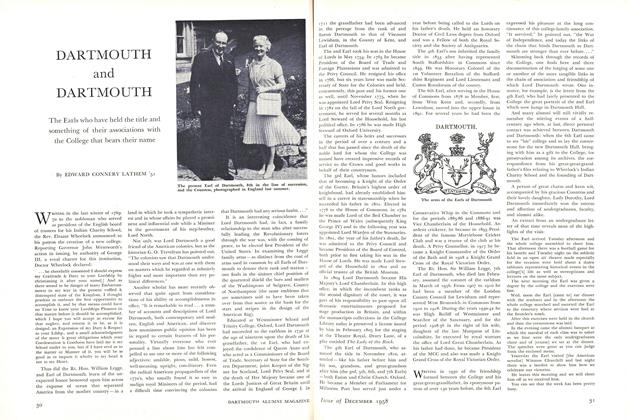

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

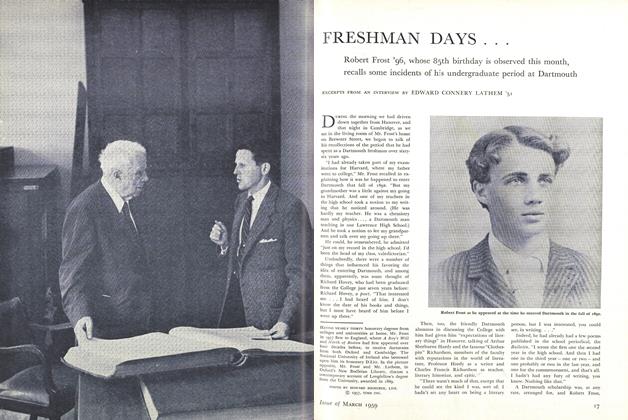

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

MARCH 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

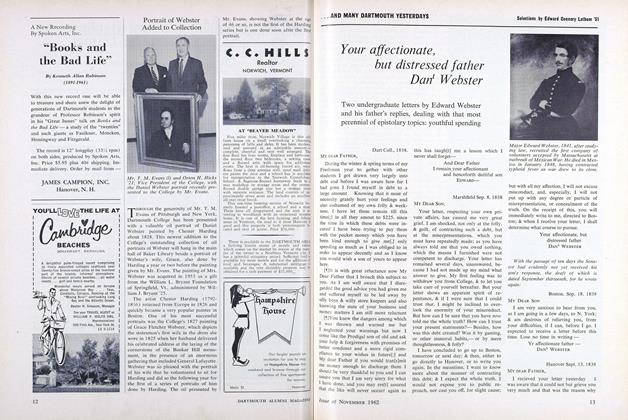

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Article

ArticleYour affectionate, but distressed father Dan' Webster.

NOVEMBER 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

FEBRUARY 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Feature

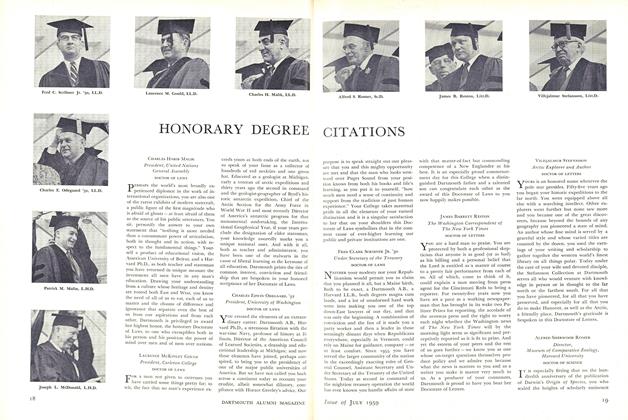

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureA Student View of the Crisis, 1816-19

FEBRUARY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureGISH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Changing and Unchanged

JULY 1967 By DR. WALTMAN WALTERS '17 -

Feature

FeatureOpening Assembly

October 1951 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY