Some Reminiscences of Channing H. Cox '01

ALTHOUGH diffident about the achievements of his own career in law, politics, and banking, Massachusetts' former-Governor Channing H. Cox '01 has an obvious pride in the accomplishments of his brothers, all three of whom made their way to the top in their chosen fields. Sitting in the study of his Boston apartment recently, Governor Cox immediately diverted the conversation from himself and began speaking of his celebrated and distinguished older brothers.

The eldest was Walter, who from his earliest years was exceedingly fond of horses and of trotting racing in particular.

"When he got to be twenty-one," his brother remembers, "he decided that that's what he wanted to do, and all his life he lived an outdoor life: training and driving horses and then having stables "

In many ways he was, the Governor feels, "the most successful of any of us." Top money-winner for many years as a driver on the "Grand Circuit," internationally famous as a breeder, and unequalled as a trainer, he was the long-time dean of the American trotting horse fraternity, and even today, eighteen years after his death, Walter Cox remains a legendary figure in the world of harness racing.

Two years younger, Guy Cox '93 was the first of the brothers to go to Dartmouth.

"He was quite a good student," concentrating not only on languages but, also, on mathematics. "He loved both of them, and although he got into law and then into business, all his life his relaxation was reading Latin and some of the old Greek plays and solving technical mathematical problems."

"In college he was musical," Governor Cox declared. "He played the chapel organ and the organ in the church, and he was accompanist on the Glee Club. And he and Willard Segur put together the music for 'The Dartmouth Song.' " (For many years the College's Alma Mater, it is now generally known by the title 'Come, Fellows, Let Us Raise a Song.")

Graduated as valedictorian of his class, Guy next took his law degree at Boston University. "Then he went into practice," his brother continued, "and he got so that he specialized in insurance law and public utilities.. ..

"He represented several of the insurance companies, and finally he became counsel for the John Hancock Company. Then he became president. He was president for several years, and then he was chairman when he retired."

In addition to being the head of one of the nation's leading life insurance firms, Guy Cox maintained a number of other business associations and, in his early career particularly, took an active part in politics, including terms on the Boston City Council and in both the Massachusetts House and Senate.

The third brother, Louis '96, was also graduated from Dartmouth. "He wasn't valedictorian," Governor Cox revealed, "but he was Phi Beta Kappa." Adding with a twinkle, "I was the only one that just got by. I never had any scholastic honors, but I never flunked an examination."

After a year at the Harvard Medical School, Louis Cox, following in the footsteps of his next-older brother, entered the B.U. Law School and, as his brother had done, took his degree with high honors. He practiced briefly in Boston, then moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he has been a prominent citizen over the past sixty years.

Engaged principally in trial work with civil and criminal cases, he pursued private practice there until appointed to the state's Superior Court in 1918. In the meantime, he had served as a member of the Republican State Committee and the Massachusetts Senate, as Postmaster of Lawrence and as a District Attorney.

Among his conspicuous services as a Superior Court Justice, his brother called attention to Judge Cox's instrumentality in the introduction of the "Jury Pooling" system and the "Pre-Trial Plan," both of which have been responsible for vast economies in time and money within the court.

In 1937 the Judge was elevated to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, where he served with distinction until the time of his retirement in 1944.

THE youngest of the four, Channing Cox himself entered Dartmouth with the Class of 1901.

"I really think one of my principal memories of Dartmouth," he reminisced, "was the chapel services Sunday afternoon. Then it was compulsory.. . . When we went over there at half past five in the fall and the winter it would be dark in the shadows there, and then President Tucker always spoke to us if he was in town. For about ten or twelve minutes the whole audience would be spellbound. I mean there was absolute silence. He made a great impression on us. And I can see him there; I don't remember what he said, but I remember that he was challenging us and pleading with us to do the best we could. That's one of the strongest memories of my College course.

"I had a really great affection for some of the professors," he said, speaking in particular of Charles Darwin Adams, then Lawrence Professor of Greek. "He was the most stimulating professor that I ever had. . . . Old 'Charlie D.,' he kept us on our toes, and I remember," he chuckled, "how fortunate I thought I was at the end of one year. He proposed to let a little group of us out of the final exam, and we'd go up to the Bema and sing a Greek chorus, marching around in the new mown hay. That was better than sweating out an examination!

"Then 'Clothespins' Richardson was a lovable character; he stimulated you to read. That's another thing that Dartmouth did for me, stimulated my interest in, I think, good books - good literature and history and biography.

"When I entered College, my first two years I roomed at Crosby Hall, and it was then one of the newest dormitories," he said as his mind ran back to that initial period of his undergraduate career. "There were only about six of us 1901 men, freshmen, and the rest was given over to 1900. They were the roughest, meanest crowd that ever was assembled, and they visited us almost every night the whole first fall. We used to be afraid to go to bed," he laughed; "they were terrible.

"I've come to find that some of them are good friends now, but we did hate them that first fall. They were rough on us. Perhaps they put us in our place all right."

Another, more solemn memory of his freshman year was the wild, snowy night when he heard the beating of a drum, and voices outside his windows announced the startling news that, "The battleship Maine has been sunk by the Spaniards." Excitedly he joined the group, "and we went around to the various dormitories and ended up in the snowstorm down on the campus." There they held an impromptu "Down with Spain" patriotic rally.

The shock of that night was an unforgettable experience: "We hadn't," he commented, "got used to wars in those days."

'Of course," he continued, referring to his classmate and Dartmouth's future President, Ernest Martin Hopkins, "I remember Hop very well when he was an undergraduate; I can see him now. . . .

"Hoppy had two sides: he was always serious, and yet he liked a good joke and saw the funny side of things.

"Of course, he was the editor of TheDartmouth the last year. That took so much of his time that we didn't see quite so much of him as some of the other fellows, but we always knew that he was out of the ordinary mold - a little 'something on the ball' that the rest of us didn't have."

Although he modestly maintains that for the most part his college life -was "fairly uneventful," he was as an undergraduate on the editorial board of the Aegis and, like his brother Guy, was very active musically. A member of both the chapel and church choirs, he was also a member and the accompanist of the Dartmouth Glee Club.

Going on, Governor Cox spoke of an amusing incident that occurred during the winter of one of his Dartmouth years.

"We had a professor that we all liked very much, Herman Home. He came there to teach philosophy. It was a very interesting course, and he was a great fellow.

"We used to have a big meal at noon in those days, and," he remembers, relative to the time in question, "after lunch I went down on the river and skated for half an hour or so and then went to his class at two o'clock.

"Right near the first part of the afternoon he called on me to recite, or asked me some questions and so forth, and I did. Then I sat down, and between the food and the heat in the room and no air and thinking my chore for the day was all done, I went fast asleep, . . .

"I was having a peaceful time, until finally I heard a 'Wah-hoo-wah' and 'Chan,' 'Chan,' 'Chan.' The whole class had sneaked out, and in the rear of the room they gave this yell that woke me up.

"Well,, that happened then," he said with evident relish as he went on to tell of the sequel to that episode in Dr. Home's philosophy class of long ago.

"When I was first elected Governor, I got a very nice letter from him speaking nicely about it. He said when he looked back he was relieved to think that he had not kept me awake long enough to sap my health. I knew what he meant."

ONE of the most important things in my four years at College, and for that matter the three years at law school, were my summers. I was a newspaper correspondent up in the White Mountains. I was up there seven summers, one after the other.. . .

"At that time the White Mountains was one of the oldest summer resorts. It was an old one. People didn't have summer homes in those days the way they do now, and a lot of prominent men and their families used to spend the whole summer up there .. ~ and I had contact with them one way and another, going for interviews and so forth. .. .

"This might be of a little interest," he went on. " 'Uncle Joe' Cannon was up there at the Mount Washington. He was then the Czar and had as much to say about legislation as the President did.

"I remember in the summer of 1901 there was a little panic down in Wall Street, and the paper wanted me to have an interview with him to see if he had any statement to make. So I waited for him there at the Mount Washington Hotel one night when he was comingout of dinner.

"I made up to him and told him that I was a reporter for the Boston Globe and the Associated Press, and they wanted to know if I'd get a statement from him.

"He says, 'Young man, do you know the reputation I have with the Washington correspondents?'

"I said, 'I know they think you're a very interesting character.'

" 'Well, I have the reputation that they never get anything out of me. I keep my mouth shut.'

" 'Well,' I said, 'it would be a great feather in my cap. I'm just a college student up here working this summer, and it would help me quite a lot.'

" 'Well, that's nice,' he said; 'I approve of that.'

"Walking along with me he stopped at the cigar counter, and he bought two great big cigars all wrapped up in fine paper. He took one and unwrapped it and lit it, and he gave the other one to me; and he said, 'Now you've got more out of me than any of the Washington correspondents, and,' he says, I'll have to go and join my friends now.' "

Had he at any time during this period felt that he might go on with journalism professionally?

"No," responded the former Governor, "I always thought I'd want to follow my brothers into the law."

Although they had both entered the Boston University Law School, Channing, along with some of his college classmates, decided on Harvard. "I, like most Dartmouth men of that time," he chided with mock seriousness, "didn't see a thing that could possibly be good about Harvard. But I had three fine years out there and made very good friendships with a lot of boys. ... I've kept contact with many of them all these years."

On leaving law school, he spent two years in the office of his brother Guy before forming a partnership with Davis B. Keniston, Dartmouth 1902, who in later years became chief judge of the municipal court of Boston. The two men practiced together, along with subsequent partners, until Governor Cox retired from the law, and they continued their close personal friendship over all the succeeding years.

The senior partner of the firm began at an early stage to take something of an interest in politics. "We used to have a Good Government Association that investigated candidates for the city govern- ment," he said, "and then made reports on them. Fellows volunteered for that work, and I got into that a little bit. Then I got interested in the ward committee work, getting people on the lists and getting them out to vote.

"First thing I knew, some of the boys thought I ought to go to the Common Council here in Boston . . . , so I was elected to that two years. And then there came a vacancy in the district for Representative, and I went there.

"I thought it would be a great thing to be in the legislature a couple of years. It might help me in my law practice. Before I knew it, I had been up there on the Hill fifteen years!"

He served nine years in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the last three as its Speaker. Then in 1918, he was elected Lieutenant Governor, when Calvin Coolidge moved up from that post to the governorship, succeeding Samuel W. McCall, Dartmouth 1874.

After having been re-elected to that office in 1919, he was, during the following year, elected to succeed Mr. Coolidge; and, due to a change in the state constitution, became the first man to serve as Governor for a two-year term. Elected again in 1922, he held the office a total of four years.

One of the many interesting' features of his years at the State House immediately after World War I was the arrival during that period of a series of famous visitors from abroad. Usually these distinguished guests were formally welcomed by the state with official functions in their honor.

He spoke particularly of the coming of King Albert and Queen Elizabeth of Belgium and with them Cardinal Mercier.

"... I was Lieutenant Governor," he recalls of that event of forty years ago, "and Coolidge was sick, so I had to take it all over, the whole entertainment, without much preparation.

"But, accompanied by the Governor's staff, I met the King and Queen at the station.... We took them to the hotel, and then we went back a little later after they had had their breakfast, and we went to the Catholic cathedral for mass.

"They had put up a throne on the altar for the King and Queen, and Cardinal Mercier was there and Cardinal O'Connell on the other side. I suppose it was the most impressive Catholic service they have ever had here... .

"The King was a very nice fellow," he declared, as he related one of the anecdotes connected with his brief association with Belgium's monarch.

"He said to me after we had got going. ... (It was a fall day, a beautiful, warm, sunny day; and the women most of them had fur stoles on.) He says, 'l'm rather surprised that the ladies would be wearing their furs on such a lovely day.'

" 'Well,' I said, 'I don't think you realize that it's rather the style to wear them, and even on a very hot day in the summer you'll see women with any possible excuse wearing them.'

"He says, 'I suppose furs are very cheap, aren't they?'

"I said, 'No, they're far from cheap.'

"'Oh,' he said, 'I should realize that nothing is cheap except Belgian bonds.' "

This amusing exchange had occurred as the Lieutenant Governor and King were driving back from the cathedral to attend a luncheon that was to be given by the state.

"He was going to be their guest for the day," Governor Cox explained, "and there had been quite a lot in the papers about what a suitable gift would be for Boston to commemorate his visit." A golden bean pot was finally decided upon: "When it came time for the bean course, they were to serve him out of the gold pot and then leave it with him."

At the luncheon, to everyone's horror, however, these well-laid plans seemed suddenly to be thwarted, for when the intended gift was brought before him, and with every eye in the room fixed upon him, the King, after inspecting the contents of the gleaming container, waved it aside with his hand, and said, "No, thank you."

"Well," laughed the official host of the royal occasion, "it was up to Channie to step to the front, and I told him then the story.

"'Oh,' he says, 'oh, yes, I should have some.' And he called the waiter back, and he ate some o£ them."

After Albert had thus sampled the famous Boston delicacy from the golden pot, the Lieutenant Governor inquired, "How do you find them?"

To which the King replied, "I like them, but I think they're very filling."

ALTHOUGH disinclined to talk about - what he scornfully referred to as "what a wonderful Governor I was and all the great things I did," Mr. Cox did take pleasure in summoning up several memories of his gubernatorial years.

He felt his experience in the House was a great help to him in the Executive Office, for having been a legislator himself he knew, he said, "what their side of the fence looked like; and I think I had pretty good luck in getting along with them. In fact, I never had a veto overridden, and I put in a few now and then.

"I think one of the things," he continued, "that gave me most satisfaction, I could call on the very best men in this state for any sort of voluntary work."

He mentioned James J. Storrow, who "gave a whole year, practically, of his time studying the railroad conditions here in New England." And he spoke, too, of Edwin S. Webster: "I got him to head a commission to study the whole state set-up of doing business.. . , and as a result of that we recommended something which was one o£ the great reforms here, the establishment of a commission on administration and finance. And that's still held It's been a great improvement."

"Another thing," he stated, "I think any fair-minded man would say that my appointments were pretty good. I tried to get the best and in most instances I did."

As an example of one of the prominent citizens who at his urging accepted posts even at considerable personal sacrifices, he recalled a time when the courts had removed a corrupt district attorney. "I had to appoint his successor," he stated.

"Well, I prevailed on Leverett Saltonstall's uncle to take the job. He was a leading lawyer, Endicott Peabody Saltonstall; and he had a lucrative practice. If he accepted he had to give it all up. . . .

But I wanted to restore confidence in the court.

"I kept at him; and he finally said, 'Well, I wish you'd give me a good reason why I should do all this.'

"I said, 'I can give you three reasons.'

" 'Well, what are they?'

"I said, 'Endicott - Peabody - Saltonstall.'

"He said, 'I don't know.' "Well, he took it," the Governor concluded; and not only that, with Governor Cox's consent he brought into his office as an assistant his young nephew who was in later years to become the state's senior U. S. Senator.

The duties and functions of the Governor of Massachusetts are a varied mixture, and among them is the pleasant responsibility of membership on the board of trustees of M.I.T.

While he was in office, the former Governor relates, the Institute elected as its new president in 1928 Ernest Fox Nichols, who had earlier been at Dartmouth, first as a teacher and then as president. And it happened that Channing Cox back in his Dartmouth undergraduate days had, in fact, been in Doctor Nichols' first physics class there.

Now, as ex-officio trustee he was asked to welcome the new head of Technology. "And," he smiles, "I had a little fun by telling them that I had sat at his feet and now he was to sit at mine. He liked it, and they all did!"

ONE of the most interesting and valued of the many associations of his long career was, Governor Cox feels, that with Calvin Coolidge.

"Of course," he began, "I knew him all through the years. When he was a member of the Senate, I was in the House of Representatives; and when he was President o£ the Senate, I was Speaker of the House - we worked together; and then I was Lieutenant Governor while he was Governor. So that I followed him along all through that time, and my relations with him were always the most pleasant. He was a good friend.. . .

"But I might just tell you some of the personal things that happened with him," he suggested; and he went on to speak of an incident dating back to that period when he and Mr. Coolidge headed the two houses of the Massachusetts legislature.

"When you're getting near the end, the Speaker and the President get together and sort of decide which matters of legislation shall have precedence, so to be sure you're coming to an end sometime. We were doing that one time, and there was a Boston Senator, Dennis Horgan. He was a pretty good fellow, affable most of the time and all that, but he had some bill that affected his district he was bound was going to get action that session.

"Coolidge kept saying, 'Senator, I don't think that's important enough in this rush hour.'

"Well, then he'd go in on him.

"And he'd say, 'Senator, I don't think we can do it.'

"And this went on for a little while.

Finally, the Senator said to Coolidge, 'You can go to hell.'

"Coolidge says, 'Senator, I've looked up the law and I find I don't have to.'

"I've told that to other people, so that's been in the prints, I think. But it's true...."

"My wife's family came from down at Wellfleet, down on the Cape," he said, thinking of another incident. "I was down there a good deal and my wife's family had always lived there, and the first time that I ran for Lieutenant Governor, I got the unanimous vote of the town of Wellfleet, every vote in the town. And it made quite a lot of talk. (Almost always somebody's got it in for 'that old so-and-so.') It really went around the country. . . .

"Well, the next year," he recalls of his second campaign for the Lieutenant Governorship, "we were up at the Touraine Hotel getting the returns. I was up in the Governor's room.

"He was getting them direct from the Western Union . . . , and it came into the vote from Wellfleet; Cox, so many and so forth; and James Jackson Walsh, one.

"And," he reported with a grin, "Coolidge says, 'Lookout, Governor, they're colonizing on you down there.'"

As he talked, Governor Cox walked to his desk and picked up a folder from which he drew a letter dated September 25, 1918, the day after the primary election in which he had first won the Republican candidacy for Lieutenant Governor. Written on the stationery of the incumbent of that office, Mr. Coolidge, it is one of the most remarkable of Calvin Coolidge's letters, for he was not a man ordinarily given to epistolary facetiousness. The note, never before published, reads:

MY DEAR MR. Cox:

Having held the office for which you are nominated for three years, I desire to commiserate you on your prospects. It is one of the most disagreeable offices I ever had anything to do with and I have a good deal of doubt as to whether a man of your ability and imagination can make it into anything that is satisfactory to yourself.

As this is not the general opinion, I do not wish to be understood as suggesting that the vote you received yesterday was intended by your fellow-citizens as a mark of disapproval or an attempt to punish you.

Yours very truly, CALVIN COOLIDGE

Holding in his hand another Coolidge letter, Mr. Cox remarked by way of preamble that in Massachusetts when a new Governor takes office his successor does not attend the inauguration, but he does participate in a small private ceremony in the Executive Office beforehand which includes the handing over of certain traditional symbols of authority. This done, the outgoing Governor leaves the State House alone; while the new one "parades" down the hall to his inaugural.

In January 1921, Mr. Coolidge impassively went through the motions of fulfilling his part in these preliminary exercises, then, at his successor's request, he selected a bouquet for Mrs. Coolidge from among the huge banks of flowers that crowded the office and quickly departed.

It was not until some days later that the secretary, changing the large blotter on the Governor's desk discovered tucked under it a note that in terse Coolidge fashion gave expression to those sentiments he had left unspoken on inauguration day:

MY DEAR GOVERNOR Cox:

I want to leave you my best wishes, my assurance of support and my confidence in your success.

Cordially yours CALVIN COOLIDCE

January 6 1921

"A little trick he played," laughed the recipient. "He knew I'd find it sometime...."

"After President and Mrs. Coolidge were installed in the White House, they gave a dinner for their Cabinet," Governor Cox recalled. "They usually invite a few friends from the outside, and they invited Mrs. Cox and me to come and stay with them and to attend the dinner.

"They were just like a young married couple. It was the first big family dinner and exhibition socially. Everything went fine, and after dinner they had music in the big Blue Room; and the men were upstairs in what they call the Spanish War Treaty Room where the treaty was signed. (By the way, I sat beside Secretary Hughes, Charles Evans Hughes, while we were having a cigar and so forth.)

"Well, we went down, and then music was all over . . . , the guests all went home, and then we went up in the upstairs sitting room. President and Mrs. Coolidge sat around just like a young married couple and wanted to know, 'What did you hear?' What did he say?' Just as natural and homey, you know.

"Well, we were their guests there once or twice besides that.... One of the most interesting nights I ever had with him was after I got through at the State House. I was in the bank, and I had to go down to Washington on some business with the Federal Reserve Bank. So, I got into Washington and went to the Mayflower Hotel.

"Along about ten o'clock, after I'd got cleaned up and washed up and ready . . . I called up the White House office and asked for Ted Clark, who was the President's personal secretary.

"He answered, and I told him I was in Washington for a couple of days and wondered if there would be a time when I could see the President conveniently.

"He said, 'Well, of course; but,' he says, 'hold the line a minute.'

"Pretty quick the President came right on the line, and he says, 'Where are you?'

"'l'm over to the Mayflower Hotel.'

"'What are you doing over there?'

"'Well,' I said, 'l'm here for a day or two, and so I thought I'd like to drop in.'

"'I want you to come over and stay with me.'

"'Oh,' I said, 'you've got enough trouble.' (He had just got back the day before from his father's funeral.)

"He says, 'I really wish you would come over. I can send over and get your things, and you can do your business from here just as well, perhaps better, than you could there. But I want you.' He says, 'We'll be alone for lunch and we'll be alone for dinner tonight. Grace came home from Vermont and has gone to bed sick, and I'm here all alone.' He said, 'I want you. .. .'

"So, I went over and we had a lunch and we took a little ride after lunch. Then I went about my business, and we got together for dinner, just he and I. Afterwards we went upstairs to the room he liked best.

"He wanted to talk with somebody about his father. He went back and told me the whole story of his father....

"He said, 'l'm so glad, father was down here a year ago, and I had a bust made of him.' He said, 'l'm so glad I've got it.' And he went to a closet and brought out this bust all wrapped up in a cloth and put it on a table, and we sat there and he told me about the things his father had told him.

"I like to flatter myself to think he wanted to talk to me, and he could let go."

Governor Cox also spoke of the now- celebrated occasion on which President Coolidge gave him some indirect advice:

"I went down one time," he began, "to see him in Washington in his office, and his desk was all clean and all tidied up. He didn't seem to have anything worrying him.

"I said, 'With all the people you have to see all over the country and all the communications you have, you don't seem to be pressed for time at all. Now, back home in Massachusetts I'm trying to fight all the time to get ahead, get ahead, and get through so I can do some real work.' "

To this complaint on his guest's part that so much of his time as Governor was taken up in seeing people the President responded laconically, "Channing, the trouble is you talk back to them."

After Mr. Coolidge left the White House, the two old friends would occasionally encounter one another:

"He came here once in awhile. Some friend would give a little private dinner, and I would see him. And he always wanted to know how I liked the bank and all that, just as interested as any friend would be."

The last time the two men saw one another was in Vermont shortly before the ex-President died. It was during the depression, and Mr. Coolidge was having some work done on the old family farm. A single carpenter could be seen busily laboring on the roof, and as Mr. Coolidge greeted his visitor he .solemnly quipped, with reference to the repairs, "You see what I'm doing trying to relieve the unemployment situation here in Plymouth."

WHEN Channing Cox left the State House in 1925, he had as Representative, Speaker, Lieutenant Governor, and Governor, served the Commonwealth for a decade and a half without interruption.

During those years on Beacon Hill his attention had been devoted, of course, to political affairs, rather than to legal or business pursuits that would have proved financially more rewarding. "I thought," he recalls of that period, "it was about time I'd better lay a little ground for the future. So, I think I can say without being questioned, that at a time when certainly the leaders of the party wanted me to go to the Senate, I decided I was going to quit.

"After I had been away from my law practice so long I knew that I couldn't pick it up. I'd lost track of the decisions and all that sort of thing. So a great opportunity, as I thought, came to me to join the First National Bank.

"I went down there, and I hadn't been there but a few years before the Old Colony Trust Company was taken over by the same owners, and I became president of that. I kept that up until I retired at the retirement age. It has been a

very pleasant association. . . ." With the coming of the Second World War, the former Governor was called back into public service once more: "Governor Saltonstall urged me to be chairman of the Public Safety Committee for Massachusetts and organize it. I did, and we headed all the civilian activities during the war. It was a tremendous job.

"Oh, we had thousands and thousands of volunteers out on the hills watching this, that, and the other, and preparing to evacuate the cities. Fortunately, it wasn't called into operation, but the organization was there. And," he said, care- fully giving generous credit to the able workers who staffed the organization, "Mayor LaGuardia and people like that came here to see our setup."

Following his retirement from active banking, Governor Cox continued several other of his business connections, but these, too, he has now largely curtailed. Today, approaching his eighty-first birthday, he leads a quiet, but by no means isolated life. In their Back Bay apartment high up overlooking the Charles, he and Mrs. Cox continue to enjoy their wide social contacts and varied interests.

The Governor takes a special pleasure in carrying on his long-time service as a vestryman of Boston's famous Trinity Church, and his Dartmouth ties, both with the College itself and with his many Dartmouth friends, are, he affirms, as strong as ever.

Reaching out to his desk as he talked, he picked up a letter from his college roommate, Robert French Leavens '01 of Berkeley, with whom he still corresponds periodically. He spoke, too, of having as neighbors in the same building there on Beacon Street both Carl F. Woods '04 and Edward S. French '06, former Trustee of the College.

"I think the thing that surprised me most and pleased me as much as anything that ever happened to me," he said as our conversation drew to a close, "was two years ago when the Council gave me the award for service to Dartmouth.... That," he declared emphatically, "was a grand night."

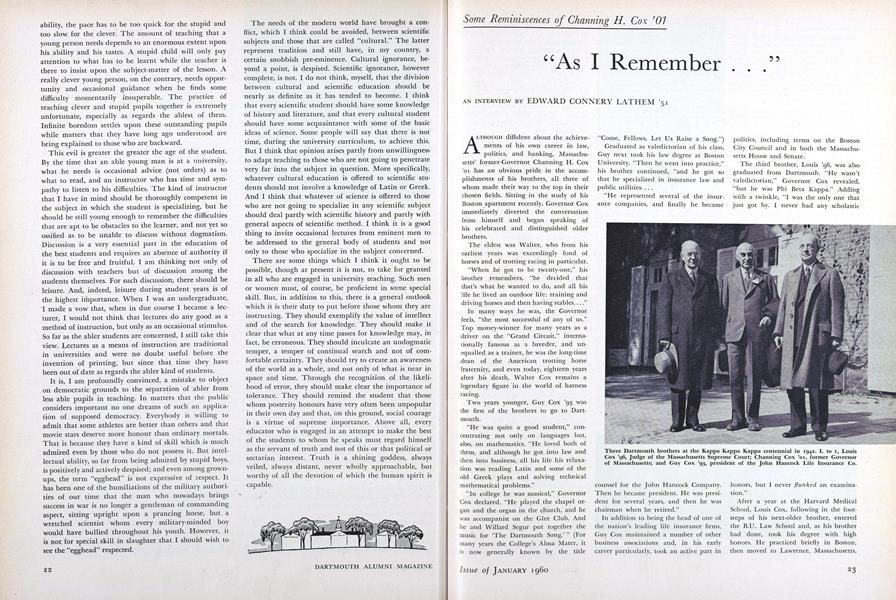

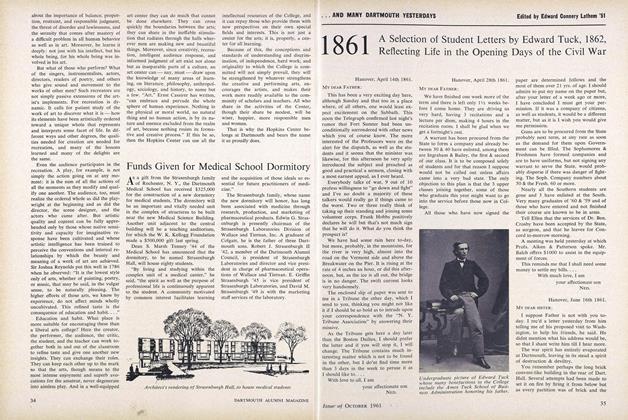

Three Dartmouth brothers at the Kappa Kappa Kappa centennial in 1942. L to r, Louis Cox '96, Judge of the Massachusetts Supreme Court; Channing Cox '01, former Governor of Massachusetts; and Guy Cox '93, president of the John Hancock Life Insurance Co.

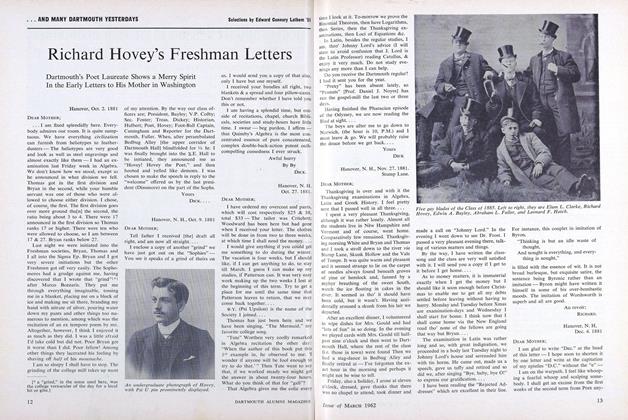

This photograph of the 1901 Aegis Board shows Channing Cox at the right end of the second row. Ernest Martin Hopkins, editor, later Dartmouth's President, is sitting first row, center.

Governor Cox shown in 1922 with Vice Presi- dent Calvin Coolidge, whom he succeeded as Governor of Massachusetts and with whom he maintained a friendship over the years.

Governor Cox (r) with Thurlow Gordon '06 (c) and George Howard '07 when they receivedDartmouth Alumni Awards in 1957. Mr. Cox was honored not only for his distinguishedcareer but for service to the College as class secretary, secretary and president of the BostonAlumni Association, and president of the General Alumni Association of Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDemocracy's Influence on University Education

January 1960 By BERTRAND RUSSELL -

Feature

FeatureA Basic Classical Library

January 1960 By PROF. ROBIN ROBINSON '24 -

Article

ArticleA Famed Collection and How It Grew

January 1960 By EVELYN STEFANSSON -

Article

ArticleReligion in the Soviet Union

January 1960 By HENRY S. ROBINSON '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

January 1960 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

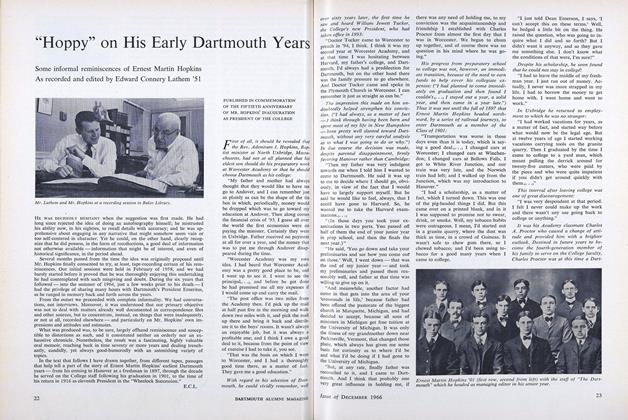

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

DECEMBER 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

FEBRUARY 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

Features

-

Feature

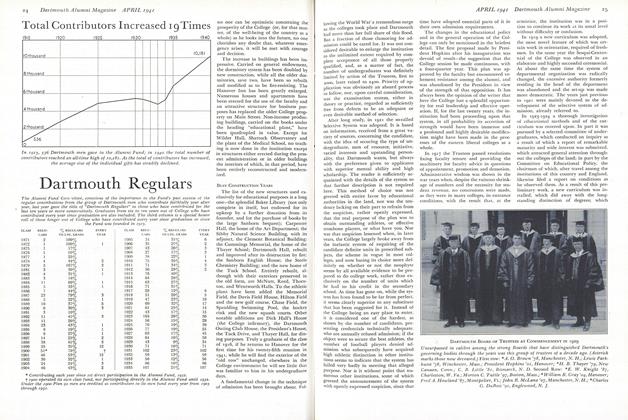

FeatureDartmouth Regulars

April 1941 -

Feature

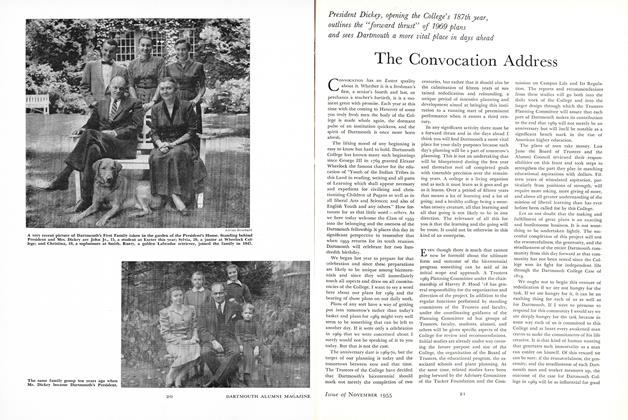

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1955 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTen Perfect Shots From The Seuss Canon

December 1991 -

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Cover Story

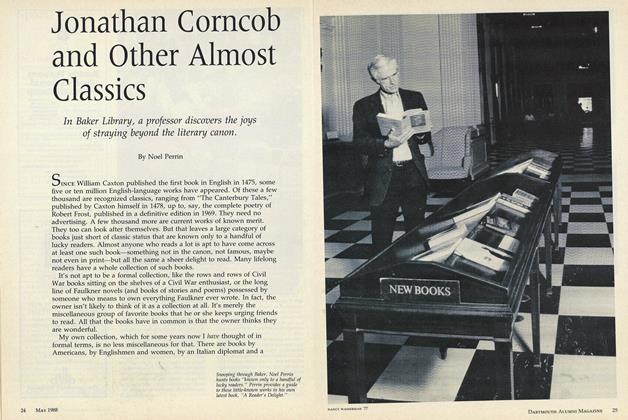

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

MAY • 1988 By Noel Perrin -

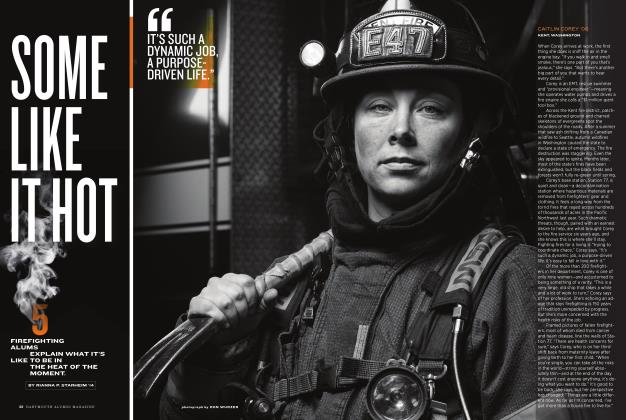

Cover Story

Cover StorySome Like It Hot

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM '14