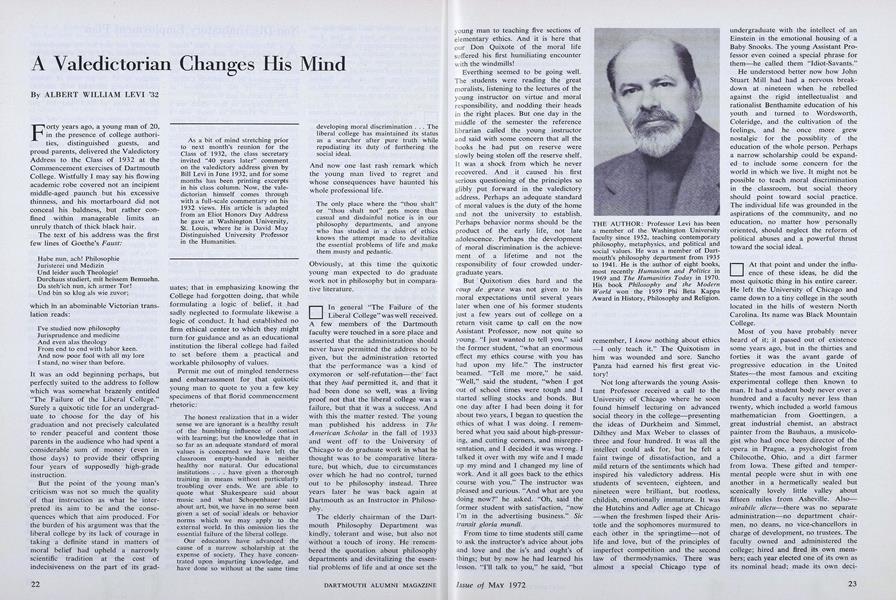

Forty years ago, a young man of 20, in the presence of college authorities, distinguished guests, and proud parents, delivered the Valedictory Address to the Class of 1932 at the Commencement exercises of Dartmouth College. Wistfully I may say his flowing academic robe covered not an incipient middle-aged paunch but his excessive thinness, and his mortarboard did not conceal his baldness, but rather confined within manageable limits an unruly thatch of thick black hair.

The text of his address was the first few lines of Goethe's Faust:

Habe nun, ach! Philosophic Juristerei und Medizin Und leider auch Theologie! Durchaus studiert, mit heissem Bemuehn. Da steh'ich nun, ich armer Tor! Und bin so klug als wie zuvor; which in an abominable Victorian translation reads: I've studied now philosophy Jurisprudence and medicine And even alas theology From end to end with labor keen. And now poor fool with all my lore I stand, no wiser than before.

It was an odd beginning perhaps, but perfectly suited to the address to follow which was somewhat brazenly entitled "The Failure of the Liberal College." Surely a quixotic title for an undergraduate to choose for the day of his graduation and not precisely calculated to render peaceful and content those parents in the audience who had spent a considerable sum of money (even in those days) to provide their offspring four years of supposedly high-grade instruction.

But the point of the young man's criticism was not so much the quality of that instruction as what he interpreted its aim to be and the consequences which that aim produced. For the burden of his argument was that the liberal college by its lack of courage in taking a definite stand in matters of moral belief had upheld a narrowly scientific tradition at the cost of indecisiveness on the part of its graduates; that in emphasizing knowing the College had forgotten doing, that while formulating a logic of belief, it had sadly neglected to formulate likewise a logic of conduct. It had established no firm ethical center to which they might turn for guidance and as an educational institution the liberal college had failed to set before them a practical and workable philosophy of values.

Permit me out of mingled tenderness and embarrassment for that quixotic young man to quote to you a few key specimens of that florid commencement rhetoric:

The honest realization that in a wider sense we are ignorant is a healthy result of the humbling influence of contact with learning; but the knowledge that in so far as an adequate standard of moral values is concerned we have left the classroom empty-handed is neither healthy nor natural. Our educational institutions ... have given a thorough training in means without particularly troubling over ends. We are able to quote what Shakespeare said about music and what Schopenhauer said about art, but we have in no sense been given a set of social ideals or behavior norms which we may apply to the external world. In this omission lies the essential failure of the liberal college.

Our educators have advanced the cause of a narrow scholarship at the expense of society. They have concentrated upon imparting knowledge, and have done so without at the same time developing moral discrimination ... The liberal college has maintained its status as a searcher after pure truth while repudiating its duty of furthering the social ideal.

And now one last rash remark which the young man lived to regret and whose consequences have haunted his whole professional life.

The only place where the "thou shalt" or "thou shalt not" gets more than casual and disdainful notice is in our philosophy departments, and anyone who has studied in a class of ethics knows the attempt made to devitalize the essential problems of life and make them musty and pedantic.

Obviously, at this time the quixotic young man expected to do graduate work not in philosophy but in comparative literature.

In general "The Failure of the Liberal College" was well received. A few members of the Dartmouth faculty were touched in a sore place and asserted that the administration should never have permitted the address to be given, but the administration retorted that the performance was a kind of oxymoron or self-refutation—the fact that they had permitted it, and that it had been done so well, was a living proof not that the liberal college was a failure, but that it was a success. And with this the matter rested. The young man published his address in TheAmerican Scholar in the fall of 1933 and went off to the University of Chicago to do graduate work in what he thought was to be comparative literature, but which, due to circumstances over which he had no control, turned out to be philosophy instead. Three years later he was back again at Dartmouth as an Instructor in Philosophy.

The elderly chairman of the Dartmouth Philosophy Department was kindly, tolerant and wise, but also not without a touch of irony. He remembered the quotation about philosophy departments and devitalizing the essential problems of life and at once set the young man to teaching five sections of elementary ethics. And it is here that our Don Quixote of the moral life suffered his first humiliating encounter with the windmills!

Everthing seemed to be going well. The students were reading the great moralists, listening to the lectures of the young instructor on virtue and moral responsibility, and nodding their heads in the right places. But one day in the middle of the semester the reference librarian called the young instructor and said with some concern that all the books he had put on reserve were slowly being stolen off the reserve shelf. It was a shock from which he never recovered. And it caused his first serious questioning of the principles so glibly put forward in the valedictory address. Perhaps an adequate standard of moral values is the duty of the home and not the university to establish. Perhaps behavior norms should be the product of the early life, not late adolescence. Perhaps the development of moral discrimination is the achievement of a lifetime and not the responsibility of four crowded undergraduate years.

But Quixotism dies hard and the coup de grace was not given to his moral expectations until several years later when one of his former students just a few years out of college on a return visit came to call on the now Assistant Professor, now not quite so young. "I just wanted to tell you," said the former student, "what an enormous effect my ethics course with you has had upon my life." The instructor beamed. "Tell me more," he said. "Well," said the student, "when I got out of school times were tough and I started selling stocks and bonds. But one day after I had been doing it for about two years, I began to question the ethics of what I was doing. I remembered what you said about high-pressuring, and cutting corners, and misrepresentation, and I decided it was wrong. I talked it over with my wife and I made up my mind and I changed my line of work. And it all goes back to the ethics course with you." The instructor was pleased and curious. "And what are you doing now?" he asked. "Oh, said the former student with satisfaction, "now I'm in the advertising business." Sictransit gloria mundi.

From time to time students still came to ask the instructor's advice about jobs and love and the is's and ought's of things; but by now he had learned his lesson. "I'll talk to you," he said, "but remember, I know nothing about ethics —I only teach it." The Quixotism in him was wounded and sore. Sancho Panza had earned his first great victory!

Not long afterwards the young Assistant Professor received a call to the University of Chicago where he soon found himself lecturing on advanced social theory in the college—presenting the ideas of Durkheim and Simmel, Dilthey and Max Weber to classes of three and four hundred. It was all the intellect could ask for, but he felt a faint twinge of dissatisfaction, and a mild return of the sentiments which had inspired his valedictory address. His students of seventeen, eighteen, and nineteen were brilliant, but rootless, childish, emotionally immature. It was the Hutchins and Adler age at Chicago —when the freshmen lisped their Aristotle and the sophomores murmured to each other in the springtime—not of life and love, but of the principles of imperfect competition and the second law of thermodynamics. There was almost a special Chicago type of undergraduate with the intellect of an Einstein in the emotional housing of a Baby Snooks. The young Assistant Professor even coined a special phrase for them—he called them "Idiot-Savants."

He understood better now how John Stuart Mill had had a nervous breakdown at nineteen when he rebelled against the rigid intellectualist and rationalist Benthamite education of his youth and turned to Wordsworth, Coleridge, and the cultivation of the feelings, and he once more grew nostalgic for the possiblity of the education of the whole person. Perhaps a narrow scholarship could be expanded to include some concern for the world in which we live. It might not be possible to teach moral discrimination in the classroom, but social theory should point toward social practice. The individual life was grounded in the aspirations of the community, and no education, no matter how personally oriented, should neglect the reform of political abuses and a powerful thrust toward the social ideal.

At that point and under the influence of these ideas, he did the most quixotic thing in his entire career. He left the University of Chicago and came down to a tiny college in the south located in the hills of western North Carolina. Its name was Black Mountain College.

Most of you have probably never heard of it; it passed out of existence some years ago, but in the thirties and forties it was the avant garde of progressive education in the United States—the most famous and exciting experimental college then known to man. It had a student body never over a hundred and a faculty never less than twenty, which included a world famous mathematician from Goettingen, a great industrial chemist, an abstract painter from the Bauhaus, a musicologist who had once been director of the opera in Prague, a psychologist from Chilocothe, Ohio, and a dirt farmer from lowa. These gifted and tempermental people were shut in with one another in a hermetically sealed but scenically lovely little valley about fifteen miles from Asheville. Alsomirabile dictu—there was no separate administration—no department chairmen, no deans, no vice-chancellors in charge of development, no trustees. The faculty owned and administered the college; hired and fired its own members; each year elected one of its own as its nominal head; made its own decisions about educational policy, financing, and direction by majority vote; lived closely with its students; cooperated with them in academic courses, creative work in the arts, and manual labor in the fields of the college farm. If the University of Chicago, thought our young Assistant Professor, was big and bureaucratic and impersonal, Black Mountain College was small and democratic and intimate. He viewed the transition as the romantic Barsodi enthusiasts of the time viewed the flight from the city to an idyllic rural life—from the big-city brain factory to an organic educational community.

Alas! it was not to be quite that idyllic. "Everything," a famous Chinese sage has said, "has lumps in it."

So ambitiously experimental, so utopianly conceived an educational system was bound to be limited and inharmonious in its results. A faculty which both teaches and administers is fated to discover that problems of policy engage it more and more, leaving less and less time for the classroom and for personal research. An education which devotes itself to artistic creativity, manual labor and the intellectual life will necessarily attract those who are more interested in community than in the cultivation of the mind, more concerned with the arts and crafts than with facts, principles, and intellectual methods. But one of the most serious difficulties was inherent in the very instability of an experiment without tradition, without guideposts except in the fleeting intuitions of the individual self, without any guarantee of permanence other than whim and the good will of one's associates. The average faculty member remained at Black Mountain no more than two to three years, the average student between a year and eighteen months, and the consequences for educational continuity were devastating.

But the most disillusioning fact of all was the way that at Black Mountain the political process was transformed into a communal fever. The young Assistant Professor had been attracted by the hope that the aspirations of the community would purify social practice, that educational idealism would flower in a small society capable of responsible self-government. What he was completely unprepared for was the bitter personalization of politics, the dogmatism of faction, the way the community at the slightest excuse suspended classes, seminars, laboratory periods, and gave itself up to weeks of uninterrupted feuding. Partly this was seasonal. In precisely the same way as an economist would chart the rise and fall of the level of prices, so a sociologist might have constructed a chart registering the Black Mountain political fever. Tempers rose and the feuding began with the falling of the oak leaves in the autumn and the flowering of the dogwood in the spring.

And what was worse, the political labels of the outside world—far away as it sometimes seemed from the isolation of this magic valley—took on a particularly dark and bitter coloring in this unusual setting. The claims of Labor were debated as by the Spanish Inquisition, gentle Quakers grew apoplectic with rage as they argued the merits of pacifism to the unbelievers, proponents of the class struggle were prepared to liquidate their more conservative opponents then and there. Sometimes, not often, this produced a philosophic impulse or a creative idea. One spring an instructor far far to the left was not reappointed, and the college gave itself up to petitions, protest meetings, sulking, and the suspension of classes for a full six weeks before normal life was resumed.

But out of the entire episode came one memorable poem by a gifted member of the community. It was entitled "The Way A Man Eats Is Political," and went as follows:

The way a man eats is political.

For political reasons is for human reasons, confidence vote is not entirely politic.

We fired a man from our faculty one year And students of course asked why. For political reasons?

If for political reasons unfair.

If for political reasons then unjust, was it for political reasons?

Yes if politics are in the house, if they live across the cove then no No if politics is party, if the way a man governs himself yes only then.

I find it hard to answer honestly with care those who ask is it for political reasons because I think about it differently.

I don't think politics when a man intimidates, I think human; what he conceives politically grows face and hands, image of government is self-portraiture. I don't see departments, I see whole and I see features some of them maybe political, pressing it outward.

Fruit grows on a tree, unless my eyes deceive me.

If I don't trust a man, his politics are not the cause, Though they too stem from roots. So all I finally say is Yes and no. And I find more and more that I say more and more yes and no when I am asked if I think something is true, because I don't think of what is true as any phrase one safely keeps.

I don't think ever so well chosen words are likely to do the trick or knowledge is now our homing-pigeon home.

I think of continually circling about and edging in, But I wouldn't care much for a truth that was "for political reasons." It would be smaller than a man.

The Black Mountain experience was remarkable for the way in which out of the thorns and nettles of conflict and absurdity one could from time to time pluck a bloom of human truth. Still, the day came when our protagonist found that a few memorable poems were not enough. He began to long for conventional courses and credits, a fixed schedule, an uninterrupted semester, quiet hours in a library unhaunted by the claims of labor, pacifism, or the class struggle. He began to feel a warm glow at the thought of a department chairman, a dean, a trustee, even a vicechancellor in charge of development! And on that day the demon of Don Quixote was forever dead in his bosom, and Sancho Panza had won the final, the conclusive, the ultimate victory.

Forty years, as I have said, now separate that Dartmouth valedictory address, "The Failure of the Liberal College," from today's thoughts on "The Success of the Liberal University," about which, paradoxically enough, I have so far said nothing. But if what I have said sounds somewhat autobiographical—more like a chapter out of the Confessions of St. Augustine than a directive from the war manual of some educational Bismarck or Hindenburg, the reason is this: all solemn pronouncements about education, all statements of principles, all enunciations of an educational credo are but the paper currency or promissory notes which must be backed up by the gold coin, the treasury reserves, so to speak, of personal experience which gives them solvency and fiduciary weight. My own convictions of what constitutes the success of the liberal university are very simple—and they can be stated with great brevity—only, it is important to have indicated, the bias from which they spring, and the life experience which is their foundation.

Already from the experiences themselves, the main outlines of the credo must be apparent. Unlike Socrates I do not believe that moral virtue can be taught—not at least at the university level. Like Plato, I believe that politics takes away from the life of the mind—at least I believe this to be true for the average undergraduate and his professors. It therefore follows that I am not in sympathy with J. Edgar Hoover's proposal that the American University should be a chief ally in the fight against "Godless Communism and crime" nor, to speak on a very different level indeed, with the suggestion of my friend Mr. Harold Taylor, made some time ago, that "It is the function of the university to encourage social change and to find within itself the instruments of social change both for the world and for its own society." This sounds to me very much like megalomania, and it leads, I think, to that kind of political activism in which the university usurps the duties and prerogatives which belong elsewhere. Mr. Taylor was very explicit as to his meaning. "The Liberal Arts College of Washington University," he said, "is the place where students should be taught how to improve the quality of American democracy by working on the race issue, where they should be directly taught how to engage in political controversy by knowing where the people are who are doing the things which are antidemocratic and where the people are who are themselves democratic in instinct and are trying to move the upward to higher levels of achievement." The statement is by itself a veritable mare's nest of ambiguity and confusion, and it confidently asserts much more than it can possibly prove. If we took it seriously we should have to design a new course for the Political Science Department. Its description would read as follows: "Political Science 627, Political Clairvoyance. The aim of this course is to identify the people who are doing the things which are antidemocratic and to locate those who are democratic in instinct. Prerequisites for taking the course: Unassailably certain knowledge of the meaning of the words 'democratic' and 'undemocratic' (see Philosophy 480, Semantics) and twelve hours of Advanced Mind-reading. Note: Graphology and Phrenology may be substituted for Mind-reading by special permission of the instructor."

I address myself to Mr. Taylor's remarks because, as one of the most enlightened representatives of the optimistic, activistic, liberal mentality of our age, they are peculiarly characteristic of a tendency which I find profoundly dangerous to the success of the liberal university—the desire to abase the values of knowledge and appreciation before the values of action. It is a symptom of our disease that some of the most remarkable apostles of the modern mind, to a man pragmatists in education, clamor for "politics first"- for they have a fixed idea concerning social reform, and they see the need to put it into action. Speaking in the name of the most exalted moral values, they have succumbed to political passions and social resentments. This is only what a generation ago M. Julien Benda called "La Trahison des Clercs"—the treason of the intellectuals—their tendency to forsake the realm of mind in order to superintend "the intellectual organization of political hatreds"—and it has only multiplied and expanded in the years since Monsieur Benda wrote.

The custodians of learning in the university should be precisely those whose activity is essentially not the pursuit of practical aims, but whose joy is in pure speculation or in the learned tradition or in creating a new organization and structure of the arts and sciences—men whose influence and whose life is in direct opposition to the insane "practicality" of the political arena and the misguided "realism" of the multitude.

For this approach to the modern university there is a long and vital tradition. Men like Goethe and Newton, Leonardo da Vinci and Copernicus were supremely indifferent to politics and the passions it engenders. Setting an unparalleled example of attachment to the purely disinterested activity of tHe mind in science and in art, they created belief, almost amounting to mystic vision, in the supreme value of this mode of existence. And even men like Erasmus or Immanual Kant, gazing almost with horror upon the conflict of human passions and the political fanaticisms of which they were engendered, preached in the name of a universality transcending nationality, religion, race or economic system abstract principles superior to these passions and directly opposed to their cruel and unenlightened progress.

The success of the liberal university is shown not when it is a mirror of the passionate confusion without, but when it is the tender mother—the almamater—of the potentialities for excellence within; not when it teaches students, as Mr. Taylor suggests, "how to engage in political controversy," but when rather it devotes itself to the development of their sensitivities and the promotion of their intelligence. For in the end my quarrel with Mr. Taylor's aims are not that they are wrongheaded or immoral, but that they are too limited, too modest, too specific, too adhoc, too momentary. Voltaire and Zola and Sartre are writers who have written within the context of current social problems, who were in Sartre's own terms engage—politically committed to the hilt; Montaigne, Flaubert, and Proust are writers who were not—who deplored the accessibility of the artist to merely political passions, and who were devoted rather to the inner culture of the mind and "le mot juste." It is the former who too often seem forced and dated, and the latter to whom we return perennially for the evanescent traces of the eternal in man. It is from their example that the modern university may learn its profoundest lesson.

In closing, permit me to draw upon the wisdom of that Black Mountain poem of long ago. The success of the liberal university is greatest when it makes its students aware of life and sensitive to the qualities which it offers for their appreciation, when it trains them to understand the works of the mind, to analyze ideas and arguments, weave them together with order and coherence, make sense out of experience. But in this enterprise it can never capture truth with finality; it can never secure knowledge once and for all - "our homing pigeon" finally home. The university is the place where we are "continually circling about and edging in," where the spirit of free inquiry holds sway, and where we need never feel ourselves under the compulsion of discovering and propagating a truth which was merely "for political reasons." For such a truth would be an affront to the innate dignity of the human mind. It would shame the living adventure of the intellect. "It would be smaller than a man."

THE AUTHOR: Professor Levi has been a member of the Washington University faculty since 1952, teaching contemporary philosophy, metaphysics, and political and social values. He was a member of Dartmouth's philosophy department from 1935 to 1941. He is the author of eight books, most recently Humanism and Politics in 1969 and The Humanities Today in 1970. His book Philosophy and the ModernWorld won the 1959 Phi Beta Kappa Award in History, Philosophy and Religion.

As a bit of mind stretching prior to next month's reunion for the Class of 1932, the class secretary invited "40 years later" comment on the valedictory address given by Bill Levi in June 1932, and for some months has been printing excerpts in his class column. Now, the valedictorian himself comes through with a full-scale commentary on his 1932 views. His article is adapted from an Eliot Honors Day Address he gave at Washington University, St. Louis, where he is David May Distinguished University Professor in the Humanities.

ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32

Features

-

Feature

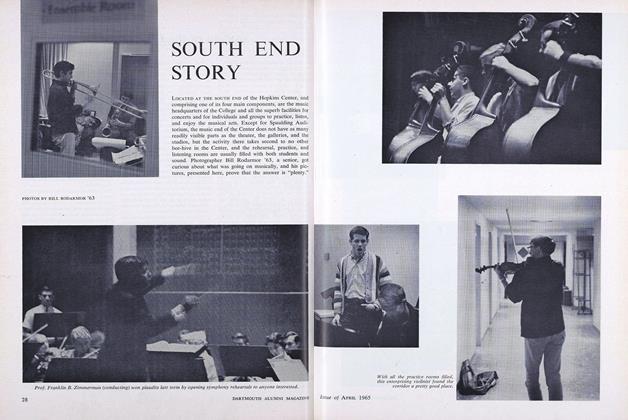

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

APRIL 1965 -

Feature

FeatureClass Association Delegates Meet to Discuss Coeducation

JULY 1971 -

Feature

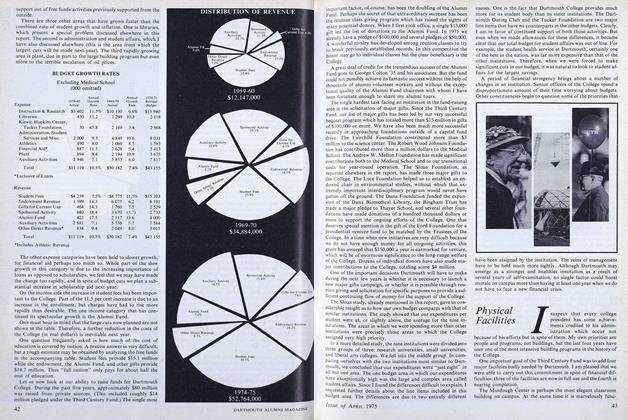

FeaturePhysical Facilities

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureSHUE HAPPENS

DECEMBER 1996 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

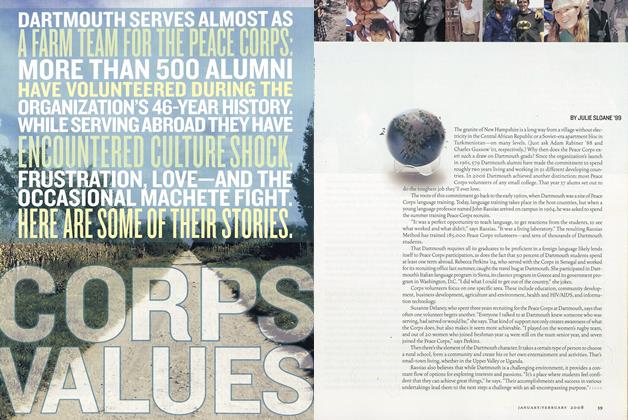

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

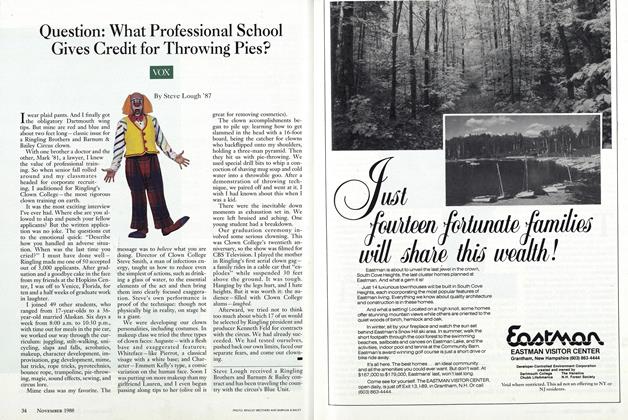

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

NOVEMBER 1988 By Steve Lough '87