By Budd Schulberg '36.New York: Random House, 1955. 320 pp.$3-95.

From the very beginning of motion pictures a successful movie has invariably bred a "novelized version" which rode on the picture's popularity as a sort of "hitch hike." I cannot recall offhand that any of these novelized versions were very palatable and most of them were a distinct letdown after the original motion picture. This was because the writers of these novels were hacks, unfamiliar with the basic material of the movie and had only the film itself for their second hand inspiration. The cold fact remains that they were in general bloodless recountings of a once thrilling story.

Waterfront, by Budd Schulberg, is the novelized version of a highly successful film, but any similarity to earlier novelized versions of other films ends there. Budd Schulberg wrote the script for the movie. The research, the creation of the script, as well as the actual making of the movie on the waterfront locations, added vividness to this later retelling of the plot. Thus this impetus for the movie was transferred - still fever hot —to the novel.

The atmosphere of place and sight and sound and smell are horrifyingly vivid through out the novel. It has a ring of authenticity that almost removes it from even a tinge of fiction. But Waterfront is not merely a report. There is art in the telling. The long shadows of Lincoln Steffens and Upton Sinclair are cast across it. Even more artfully, in the wonderful conversations of Irish dock workers, there are overtones of Sean O'Casey. All of these various elements are astonishingly well blended into the story itself.

Any attempt to recount the plot would work a grave injustice to the novel, for it would necessarily omit most of the wonderful little characterizations and conversations which are the lifeblood of the story. They weave in and out of the plot like silver and gold thread against a leaden background. Terry Malloy, the ex-pug, and his fancy brother, Charlie the Gent; the Doyle family, Pop, Joe, and Katie, who reap the whirlwind of the corruption on the docks; Father Barry, the Roman Catholic priest who has a conscience; and, most supremely, Runty Nolan. There are literally a hundred other characters all well conceived and warmly understood that lift the melodramatic story far beyond muckraking to real human values.

Only in the case of Father Barry does the tale falter slightly. In the face of open and shut corruption, murder, and violence, as antiChristian as black is from white, that cries aloud like Abel's blood from the earth, he hesitates, and refers to the precepts of the Fathers of the Church before he acts. The jacket of the book says that he seeks First Century Christianity, but in the story he runs the gamut from Pius XII clear on back, settling finally on St. Francis Xavier as his model. But convinced, he and the plot press forward with very human anger and justifiable righteous indignation.

At this point I must confess that I am one of that small minority who did not see the motion picture. On reading the book it was never apparent that this material had been used in another medium. Waterfront stands on its own two feet as a novel. It is incisive, cruel, sentimental, and thrilling. Best of all it is always human.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStretching the Classroom To Washington—and Michigan

January 1956 -

Feature

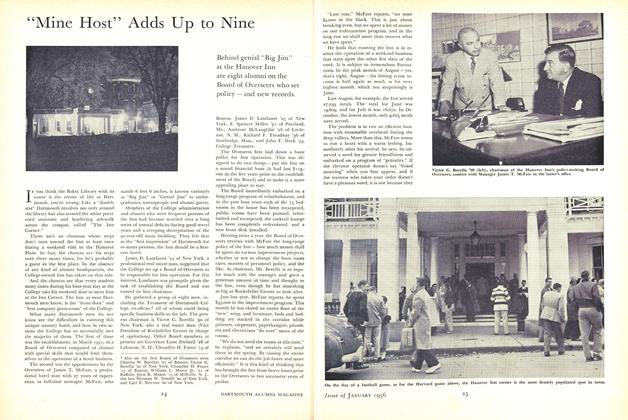

Feature"Mine Host" Adds Up to Nine

January 1956 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureMt. Washington Pathfinder

January 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

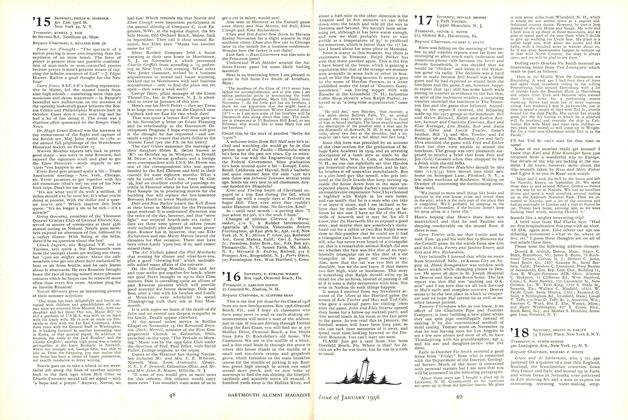

Class Notes1926

January 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

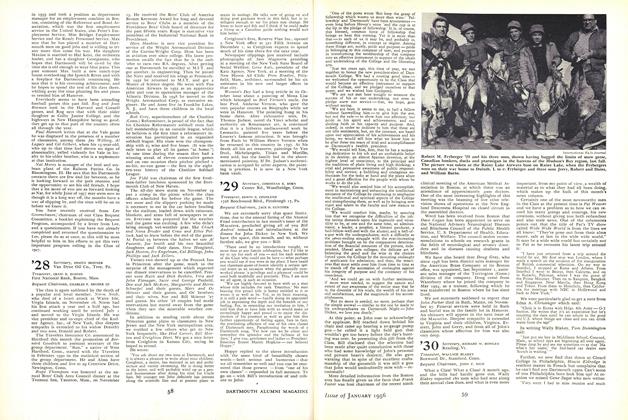

Class Notes1930

January 1956 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH

HENRY B. WILLIAMS

-

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE

January 1939 By Henry B. Williams -

Article

ArticleA Players' Report

June 1947 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE STAGE MANAGER'S HANDBOOK.

January 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksPRIVATE.

DECEMBER 1970 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE TRINIDAD CARNIVAL, MANDATE FOR A NATIONAL THEATRE.

APRIL 1972 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

DEC. 1977 By Henry B. Williams

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1920 -

Books

BooksThe Stephen Daye

March 1935 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MAY 1969 -

Books

BooksREVIEWS OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS BY ALUMNI AND FACULTY TORY TAVERN

August 1942 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksCOMBAT MISSILEMAN.

June 1962 By HOWARD F. EATON -

Books

BooksShelf Life

Mar/Apr 2004 By Matthew Feinstein '04