By Errol Hill, (Professor of Drama andChairman of the Drama Department).University of Texas Press, 1972. 139 pp.with eight color plates and twelve black-and-white plates. $10.

To many Americans the word "calypso" means a song which entered the United States about 1943; it hymned the praises of Rum combined with Coca Cola and ended with the fact that the singer was "workin" for the Yankee Dollar!" The tune, in lieu of stirring war songs, had a rollicking rhythm and was a fair antidote to "Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition!" With this song as our only background for Caribbean music, it will come as some surprise to learn from Professor Hill's book on the Trinidad Carnival that calypso singing has a long history. Its roots go back into the 18th century, and it is an art form which stems from the combined musical backgrounds of one of the most polyglot settlements in the New World. Its development is based not alone on the merging of native songs but also as an accompaniment to a far more basic activity which has been part of human existence since history began: the celebration of the rites of rebirth.

The Island of Trinidad throughout its known history has absorbed many cultures. The Indian aborigines were joined by the Spaniards in the early 16th century, and this culture was supplanted by the French, who imported African Blacks for slaves. In the 18th century the Island was taken over by the British and slavery was continued until emancipation in the early 19th century. The importation of East Indians and Chinese during that century added to the melting-pot atmosphere of the island. All these separate peoples formed enclaves under the overlordship of the upperclass French families and later under the British, and thus established a group that Mr. Hill designates as the "Plantocracy."

As in every other tightly governed classstructured civilization, at least one time during the year the underdogs were permitted a steam-valve period, during which they took over the island and indulged in revelry. The Catholic tradition established by the Spaniards and continued under the French had long prescribed the period prior to Lent as the time for festival. From the beginning on the island this period was known as Carnival. The word "carnival" itself means a wistful farewell to meat before abstinence. Mardi Gras and Fastnacht are French and German variants of this seasonal "last fling." On the island of Trinidad the tradition was well established before the British assumed control, and wisely they did little to discourage it. Essentially a folk festival in perhaps a truer and more exuberant form than many other folk survivals, it has suffered less depredation from interested outsiders who always insist on sophistication, order, and decorum.

Any indigenous folk festival, irrespective of the object it celebrates, is always in the process of evolving. The Medieval Church in permitting the populace to "take over" on the yearly "day of Asses" or the "Day of Fools" had used it as a steam valve and little realized that these revels would one day blossom into the magnificent drama and theatre of the 16th and 17th century Europe. Professor Hill has watched the Trinidad celebration from his childhood and is convinced that this Carnival contains the possibilities of a National Trinidad Theatre. His book is most convincing on this and, to prove his contention, he presents us with a thoroughly documented pageant of the historical development of this event.

In this very brilliant study we are shown the gradual adoption by the revelers of the whole panoply of theatre art to aid their parades and shows, for literally the whole Island is in Carnival. Costumes and masks of unbelievable intricacy and design along with settings and floats are pictured not only in the text but in the well-selected illustrations. The invention of "steel bands," fabricated from discarded oil drums and tempered and tuned, is only one of the exciting accomplishments by the populace. Above all, the singing which accompanies the unconventional instrumentation is filled with comic satire and sharp political commentary. The pervading note of the Carnival is one long bacchanalian cry of joy.

Mr. Hill is certainly justified, on the basis of parallel evidence, in hoping that this will grow into great indigenous theatre. Already some native Trinidadians, himself among them, have used Carnival-inspired material for plays. Last year, Dartmouth College had the opportunity to see one of these plays presented in Hopkins Center directed by Mr. Hill. This was Ti Jean and His Brothers by Derek Walcott, and it was obvious in this that the Carnival spirit prevailed throughout the evening. Mr. Hill's own play, Man BetterMan, which also stems from the Carnival, was presented in New York recently by the Negro Theatre Ensemble. And yet, as Professor Hill admits, these efforts are a halt step toward a national theatre, for they are based primarily on a European style of presentation. Something more creatively indigenous should emerge from an Island populace composed of people from four continents, each bringing to the celebration his own traditions. Already the art of song in Calypso has been developed as a unique contribution. Perhaps Trinidad is farther along on the road to true theatre than we are aware. Who knows how long after the comic song of the Komus and the tragic stanzas of the Dithyramb were perfected, did Thespis or Aeschylus come along?

The Trinidad Carnival is an exciting book which affords a glimpse not only into a neighboring culture but also into a developing art form. Had we had such an account of the Greek stage before Aeschylus we would be blessed beyond measure.

Dartmouth Professor of English and Directorof the Experimental Theatre, Mr.Williams with Mr. Hill teaches the Historyof Theatre and Drama, and by himself PlayDirecting and American Drama.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

April 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

April 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAdvocate for the Aging

April 1972 -

Feature

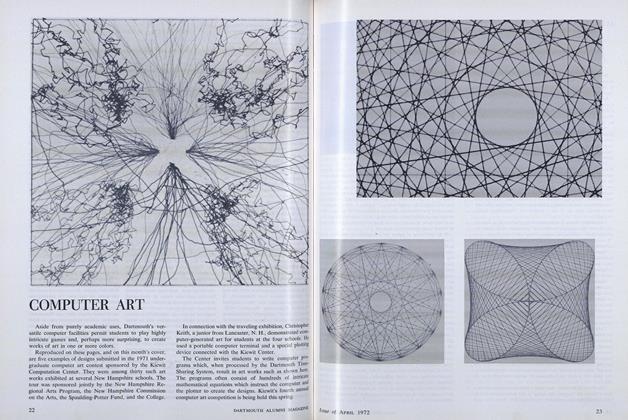

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

April 1972 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

April 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

HENRY B. WILLIAMS

-

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE

January 1939 By Henry B. Williams -

Books

BooksTHE STAGE MANAGER'S HANDBOOK.

January 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

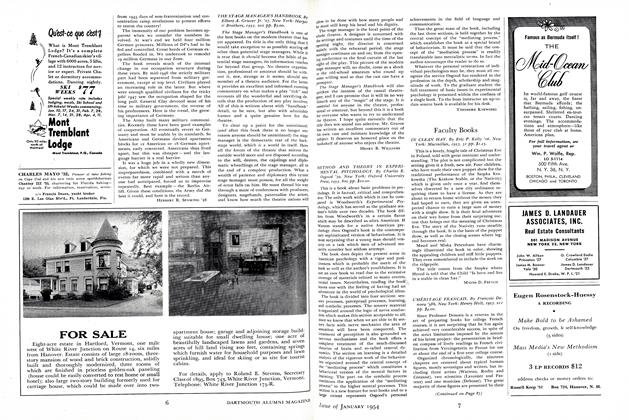

FeatureTHE EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

June 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksWATERFRONT.

January 1956 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHEATRES AND AUDITORIUMS

JUNE 1965 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksPRIVATE.

DECEMBER 1970 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

November, 1924 -

Books

BooksHenry Holt and Company, New York

FEBRUARY 1930 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

December 1960 -

Books

BooksASBESTOS PHOENIX.

DECEMBER 1968 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksTHE TELEPHONE BOOTH INDIAN

May 1942 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksTRANSACTIONS: THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN INDIVIDUAL, FAMILY, AND SOCIETY.

JUNE 1972 By MARTIN D. MERRY, M.D