Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr., '37. New York:Columbia University Press, 1963. 194 pp.,notes, index. $4.50.

The theme of this volume is at once comprehensive and elusive. To establish the genesis of American views on the relationship between man and nature, the task undertaken here, involves perplexing difficulties. Not least is the need to define popular attitudes, and in his effort to meet this need the author uses evidence as diverse as the Lowell factory system, the New Deal's Resettlement Administration, and post-1945 defense budgets. Equally difficult is the selection of individuals whose writings or policies require attention: Prof. Ekirch's decisions to discuss Andrew Jackson's view of the American Indian but not the views of missionaries (even of Eleazar Wheelock), and to consider Thoreau but not Audubon, illustrate the problem. And once having selected the articulate spokesmen whose ideas play in counterpoint against mass attitudes, the question of semantics quickly intrudes itself. For example, in expounding Emerson's ideas, the author admits that to the Concord sage "nature was many things" - among them "a physical fact or commodity, ... beauty and idealism, as well as discipline and language, . . . the spirit of the present and a prospect for the future."

Having indicated that Prof. Ekirch has plunged into a semantical jungle, let me add at once that he cuts his way through it deftly enough. In 19th Century America, he asserts, popular opinion fully sanctioned the devastation of a rich wilderness, for "obliteration of the American landscape" was the accepted price of material progress. Only a few, notably the Transcendentalists, dared criticize either this assault on American resources or the scheme of values that supported it. (And, as Stewart dall notes in his Quiet Crisis, the Transcendentalists committed to their private notebooks many of their most eloquent conservationist structures.)

Prof. Ekirch traces the stirring of American interest in conservation in the late 19th Century, when artists and scientists drew public attention to the wondrous Rocky Mountain region. Then, amidst the great degression of the 1890s, the General Land Office announced that the frontier had closed (only a half truth, as time proved), evoking concern about eventual land and food shortages. Meanwhile, such expert conservationists as Gifford Pinchot began to press for a businesslike policy of careful resource manaoement. The author treats conservationist ideology as "one of the component parts of the idea of a planned society," centering his discussion of planning on the 19305.

One of the chief contributions of this book is its analytic summary of, and extensive quotation from, recent American debate on broad questions of resource use and conservation. The quickening pace of technological change has produced renewed careless optimism about man's capacity to provide for growing resource needs. At the same time, the very complexity of this technology—, and the capacity for destruction that it gives us have forced reappraisal of the relationship of man to his environment. Prof. Ekirch makes his own position clear on such critical issues as population growth, nuclear power, and government consumption of resources; and the provocative character of his study is sharpened by his contention that among all nations historically "only the American people could afford to be improvident."

Assistant Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

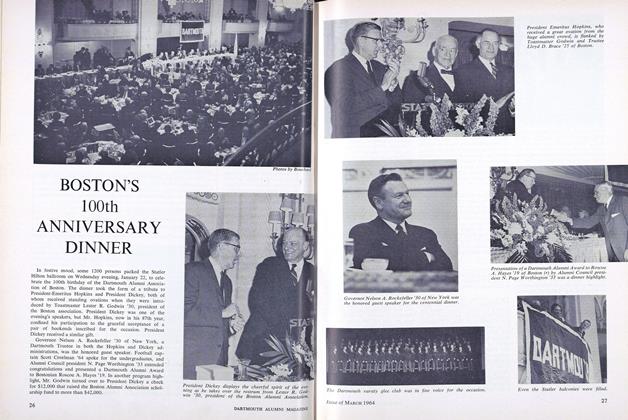

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

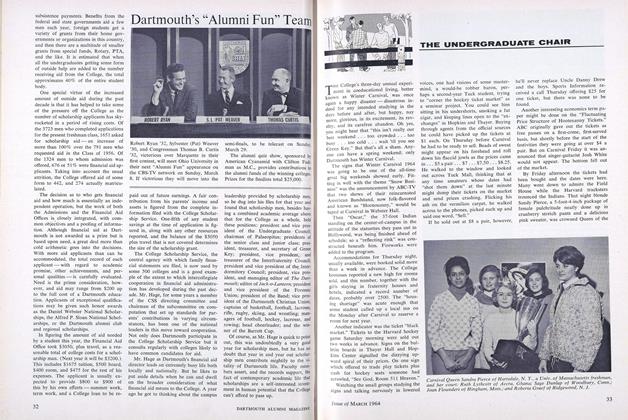

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

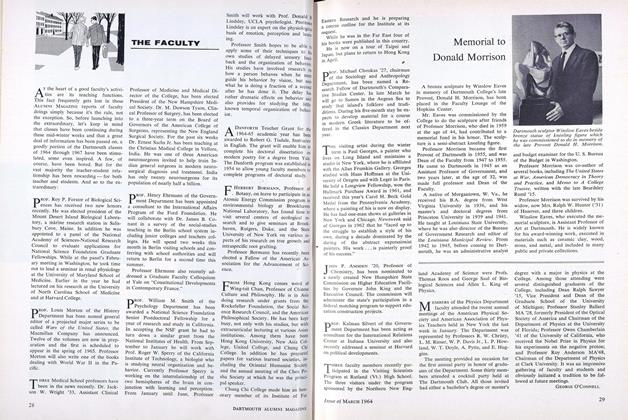

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

HARRY N. SCHEIBER

Books

-

Books

BooksUnmet Hope

MAY 1978 By DAVID DAWLEY '63 -

Books

BooksSOCIAL PROBLEMS ON THE HOME FRONT,

April 1948 By GEORGE F. THEIUAULT '33. -

Books

BooksHELPING YOUTH IN CONFLICT.

JULY 1965 By GEORGE H. KALBFLEISCH -

Books

BooksTHE ENJOYMENT OF MANAGEMENT.

MAY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksGREAT SOUL; THE GROWTH OF GANDHI

July 1949 By Philip Wheelwright -

Books

BooksTHE JAPANESE VILLAGE IN TRANSITION

March 1951 By TREVOR LLOYD