By Martin Meisel. Princeton:Princeton University Press, 1963. 477 pp.$7.50.

Martin Meisel has written a book about Bernard Shaw that tells us far more about him and the theatre that surrounded him than any number of the biographies that have appeared since his death in 1950. Any great man is always the sum of all the elements of his generation and properly to understand him we need to know the roots of his genius. Working patiently with the records of the theatre of Shaw's time from his earliest years in Dublin through the major portion of his life in London, Professor Meisel has discovered, or recovered, for us all of the dramatic fare now available to us in manuscript, photograph, and book to show us that Shaw's genius was imbedded in the theatre of the 19th Century. The book that emerges from these studies is a fascinating and exciting adventure, and one that no student of Shaw can possibly ignore.

We tend to forget that Shaw's genius was a cleansing one. That he came upon a theatre which was dominated by the great actor-manager. The artistic productions of that day were primarily the actor-manager's arrangements of Shakespeare's plays, always as starring vehicles. Beyond these the theatre offered farce, melodrama, and extravaganza. In his work as playwright he touched all these forms with his brilliant mind and created new forms out of old. His versions of these forms are so instinct with incisive wit that we are prone to forget the older base and consider Shaw as a vast innovator. Professor Meisel reminds us that he was noth- ing of the kind. Shaw himself constantly stated in his writings, especially in the prefaces to the individual plays, that he was an admirer of these forms, and that it was the substance of the older plays that needed life-giving sense applied to them. Thus Barrett's hackneyed melodrama "The Sign of the Cross" became the inspiration for the brilliant "Androcles and the Lion." Victorian melodramas paved the way for "The Devil's Disciple" and "The Shewing-up of Blanco Posnet" (both, incidentally, with American locales).

Bernard Shaw once said that he preferred to stand in the apostolic succession from Aeschylus rather than the Papal succession, which he described as being founded on a pun. This book makes it quite clear that he does stand in the succession of the great comic dramatists of the English 19th Century. As Mr. Meisel points out, the growth of the line from John Maddison Morton through Planchet to Tom Robertson and, supremely, William Schwenck Gilbert is obvious in many ways, particularly in the use of paradox. There are echoes of all of his predecessors in his work, and yet the final work is Shaw all compact.

Here is a man whose work as a dramatist has the individuality of genius not because of great originality (which he would have been the first to admit), but rather because of great clarity of mind and incisive wit. In this manner he was able to cleave through the stuffy shibboleths of his time. His inborn religious fervor which grew from a literal understanding of the works of great religious figures was expressed through Christian paradox which demands the seriousness of comedy. Mr. Meisel has done us tremendous service in reminding us of this exciting background to the work of Shaw, and further he has presented us with a sympathetic portrait of the 19th Century theatre that makes excellent reading. I can only reiterate that any future writer who tackles Bernard Shaw or his work will bypass this book at his peril.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

November 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

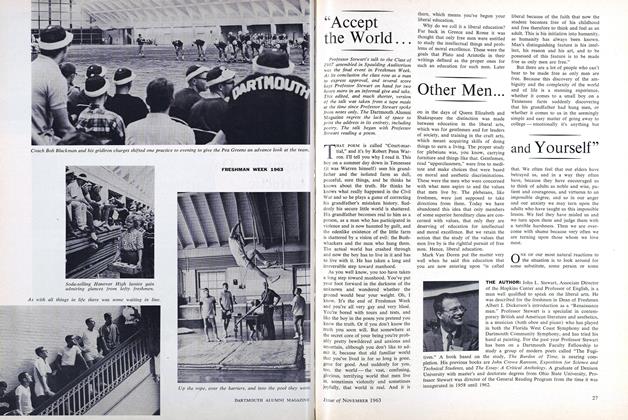

Feature"Accept the World..., Other Men...and Yourself"

November 1963 -

Feature

FeatureA TASTE FOR CHANGE

November 1963 -

Feature

Feature"Turn Our Penitence Into Dedication"

November 1963 By Reverend Richard P. Unsworth. -

Feature

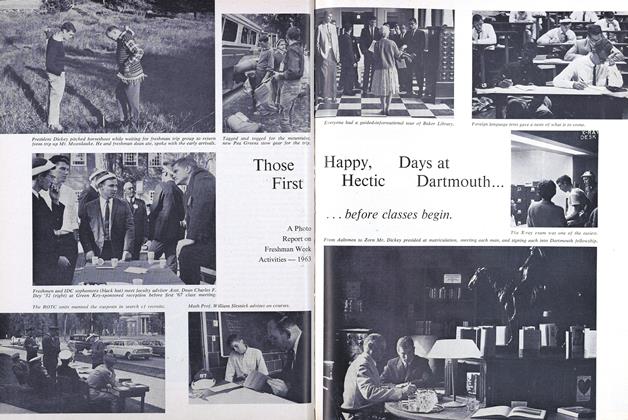

FeatureThose First Happy, Day at Hectic Dartmount

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1963

HENRY B. WILLIAMS

-

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE

January 1939 By Henry B. Williams -

Books

BooksWATERFRONT.

January 1956 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE LONDON STAGE 1600-1800, PART 4, 1747-1776.

JULY 1964 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksPRIVATE.

DECEMBER 1970 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE TRINIDAD CARNIVAL, MANDATE FOR A NATIONAL THEATRE.

APRIL 1972 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

DEC. 1977 By Henry B. Williams

Books

-

Books

BooksHenry Bailey Stevens '12

May 1929 -

Books

BooksTHE GREAT CONSPIRACY,

March 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26. -

Books

BooksENGINEERING: ITS ROLE AND FUNCTION IN HUMAN SOCIETY.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksThe Eye of the Beholder, Squinting

April 1975 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksGUIDE TO PEDAGUESE.

APRIL 1965 By RICHARD G. JAEGER '59 -

Books

BooksTHE STRUCTURE OF POLITICAL THOUGHT, A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF POLITICAL IDEALS.

JULY 1968 By VINCENT E. STARZINGER