I WAS sitting in a business office in Boston five years ago when I received a call. It is sometimes said that men receive a call. Life elects them to go one way.

This call asked if I would come to the University of Washington in Seattle and be poet in residence.

At that time I had the notion that poetry cannot be taught, that its mysterious essence eludes explication, defies analysis. I thought that poetry could not be taught by poets. I had no doubt that it could be taught by professors. Had I not learned from them, at Dartmouth, at Cambridge, at Harvard?

Then I thought o£ it as a challenge. Why should one close one's mind on the notions one already has? Why not experiment with life in the act of teaching poetry? Why should not a poet, in fact, be best suited to teach poetry? So with a burgeoning sense of adventure we crossed the country to Seattle.

It should be said for the record, and before trying to come to the nub of some problems of the poet as teacher or the teacher as poet, that the call I mentioned above was, surprisingly enough, followed by four others in four succeeding years. To recapitulate, there were two large state universities, with their special and lively problems: the University of Washington and The University of Connecticut. Then there was a call to be the first incumbent in a new Visiting Professorship at Wheaton College (Norton, Mass.), a century-old college of attractive young ladies. Then there was Princeton, with its preceptorial system, where in addition to teaching poetry I gave a series of Christian Gauss lectures. And now there is Dartmouth, a homecoming after being out in the world thirty years. Marianne Moore has as the title of one of her books "What Are Years?" The longer one lives the more poignant this question becomes.

Actually, I received my first call to poetry when I was about fifteen.

Poetry is being rediscovered. History is swinging back to its ancient magic. And there comes into action the idea that poets can teach it. There is felt to be a need for integration between poetry as an intellectual discipline, a mode o£ teeling, an intuition of the mysterious meaning of life, and the so-called real events of the real world. This action has set within our universities and colleges a dozen or more poets as poets in residence, professors, or lecturers, producing an interesting American phenomenon.

By analogy, this present feeling for the need of integration has occasioned the expenditure of money on the part of businesses and foundations to return to colleges and universities, in California, in Pennsylvania, and this past summer at Dartmouth, business executives to learn from humanistic studies what at forty-odd they may not have been abie to learn at twenty. Or to see things in a different perspective. And to see that business, for instance, is poverty-stricken if it is not understood as an integral part of the cultural life of the nation. Business and culture were poles apart thirty years ago. Now it is seen that each depends upon the other and that they have mutual responsibilities. How fine it would be if our universities and colleges could pay back the compliment and send college teachers into business offices and factories to enlarge their horizons.

Recently I came across an old notebook containing early Dartmouth or post-Dartmouth poems. On one page appears this sentence, probably written shortly after my graduation in 1926: "Life should be lived expending energy in ideas and movements rather than on people." I have copied it just as I found it. First, a word of criticism. There is an ambiguity in "and movements," which suggests some sort of social action, but I apparently intended it in strict apposition to "ideas" and meant intellectual life for its own sake.

May I pay my respects to the Dartmouth of my time in quoting this sentence? I derived the highest respect for intellectual things from my professors. At the peak of a lust for learning was almost a limitless aesthetic delight. But note the sentence. It stands solitary in the little notebook, as if I had tried to put down the essence of a college education. It is significant that before the Crash, before the Depression, before World War II, Americans were secure. One felt no compulsion to expend energy on the people. By now we have a deeper and truer sense of democracy. Perhaps a graduate of last year's class would write that sentence almost in reverse. If you put a new electric washer in your house it will not go (I can attest to this) unless a workman properly connects and adapts it. What would happen in one month if the garbage man and the trash man did not come? Society is an integrated continuum of events and these last mentioned members of it are as important as college professors or bank presidents. It took me at least twenty years to learn this.

Poetry fits into the picture too.

But while I am reminiscing let me recall to your memories a phrase from President-Emeritus Hopkins which in my day became a veritable slogan. It was "An aristocracy of brains." Intellectual values were held before us and as young men we were to go forth to conquer the world by intelligence. It was an arresting phrase and it fired us with vague but powerful ambitions. It appears now to belong to its

time as aptly as certain national slogans, such as the New Deal and the Fair Deal belonged to theirs. The movement of historical processes is complex and mysterious. It seems certain that man does not live by brainpower alone and this observation leads me back to poetry.

POETRY is in the center of life and if I had had the wit long ago I should have used a term which has been employed during the past two decades in schools of criticism. I should have asked for "An aristocracy of sensibility." That would bring to bear the whole personality, its total, potentially rich integration with the world. It would account for varieties of experience and contain the boundaries of both ambivalence and didacticism as modes of thought and conduct.

Now, in my own field, a real and troublesome problem exists. Is poetry aristocratic or democratic?

I wish to deal with this problem and to follow some considerations of it with the entertainment of another major problem, the relation of poetry and science.

Is poetry aristocratic or democratic? By this I mean to ask, does the poet, that is the great poet, or a group of leading poets, dominate the age and bring culture up to the level of the poet or poets, which may be said of Eliot in the first half of this century, or of any leading group you may name, if you agree with the proposition; or is poetry democratic in that it is judged finally by all readers through time and is actually thus an expression of the will of the people, a democratic enactment?

Let me elaborate a bit. I want to have some answers to this problem as it has troubled me for years. Is it chiefly university-bred poets and readers who keep up the standards o£ poetry? Can one make so large a generalization with effect? If this is so, it must follow that poetry is an aristocratic matter, since few minds in the masses of society are sufficiently trained to write or to comprehend the best poetry.

I would like now to take a position for the sake of argument. It is not a matter of total belief. The Higher the mind and the greater the poetry the more esoteric it becomes. Gerard Manley Hopkins is a case in point. He had only three poems of his published during his lifetime, which ended in 1889 at the age of 44. After the publication of his work in 1918 his friend Robert Bridges his value was perceived and there followed for over twenty years an outpouring of books about him. Now the outpouring of books and articles about Hopkins has subsided. He speaks to this century closely, who could not reach the ear of the last.

I love his poetry intensely along with that of Blake. Yet I recognize that even now, although Hopkins is large in textbooks and critical estimation, he is read by probably only a happy number of thousands of readers. He is thus, in my argument, an aristocratic poet. He appeals to trained readers, to sophisticated personalities. Is this a limitation in him or is it a limitation in a society which is so democratic as not to care for what he has to say?

Take another example. Carl Sandburg had a great flair during the twenties. He seemed to speak directly for perhaps a majority of Americans and to exist at the heart of our democratic culture. Sandburg represents an opposite pole from Eliot. He is not read with conviction in the universities or commented upon by the learned because he is too simple, not exciting to the imagination, and because his language is flat. We adore instead the late Wallace Stevens, who incidentally was a vice-president of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Insurance Company. Now if you grant the premise that Sandburg is truly democratic and that we have a democratic culture in America, would you not have to elevate Sandburg and his like, the practitioners of popular art, to a place they do not at present hold?

The opposite has happened. The amorphous, scintillant, radiant, difficult and subtle imagination of Stevens has held many minds in fascination. The subtle and difficult poets have won the recent day, but taste, as we know, is a see-saw, and change is inevitable.

I do not remove the posed question, but dispermit a limitation to an either-or dichotomy. I speak instead for a vigorous pantheon of poets, which we possess in this country, and for a catholicity of taste which embraces widely divergent ideas and styles with discrimination.

ANOTHER concern is the relation of poetry, as an example of the arts, and science. They seem opposite. It seems as if science has made our world what it is and that science controls it. Science makes things happen. It seems, oppositely, that poetry "makes nothing happen," to quote Auden, that it ends in contemplation, often perhaps a beautiful, disinterested contemplation, and seems to be inferior to science.

Art, or let us retain the word poetry, expresses the nature of a time. One does not understand much about the nine- teenth century by going to books to find out how many soldiers were lined up against each other at the battle of Balaclava. One may read Keats, Blake, Tennyson, Whitman, Emerson to derive a feeling of the century. We do not understand the Civil War in terms of logistics, but through, for instance, Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage, in which its main characteristics are revealed. This is a story written by a man who read about the war, but did not fight in it. His imagination has preserved in art a significance of that war.

There is no question o£ inferior or superior in relating art and science. These terms need not be applied. Ultimately they represent the same use of the intelligence, that is, imagination.

In a current book Christianity and theExistentialists (Ed. Carl Michalson, Scribner's) I read on page 61 that Einstein "assures us that science can deal only with the function and interaction of matter,

but can never know or penetrate into the nature of matter." He also said somewhere that in inventing a new theory of the universe the mind "jumps a gap." At some fine point his mind jumped a gap from what was then known to something new. He saw things in a new way and produced his Relativity and Field Theory. It seems easy now to conceive of time as a fourth dimension. Not one of our grandfathers could think of it in that way. This was essentially poetic imagination.

Mr. Eliot, when he wrote The WasteLand, which was published in 1922, in effect threw over the nineteenth century. He invented a new type of poem, he saw things in a new way.

Thus, at their peaks, scientific and poetic imagination are equated as uses of intelligence - sensibility too, if you will. They are branches of the same tree, they have the universal roots of our common humanity.

Science is based on reason; it is limited to measurement. Poetry is often based on intuition, which has a deep, ancient resource yet has its own limitation inasmuch as it depends on a predilection whether one feels that it creates a world-view and whether this world-view engages one. Many intelligent people have got from birth to death without art at all.

I HAVE given only two problems which a teacher of poetry could deal with. If an undergraduate could study, to the limit of his imagination, applying all the agility of a youthful mind, and could he satisfactorily answer, with a battery of scholarly arguments, such questions as these he might not only enjoy himself immensely but he might move toward one end of education which is self-knowledge.

A formulation above does not quite satisfy me. One wishes to avoid special pleading, yet allow me a confessional stance. Auden said recently somewhere something to the effect that when he is in the presence of scientists he feels inferior. He feels out of place in the presence of these rulers of the world. It is an intelligent attitude, but there is a whimsical, crafty undertone in the sentence, as if he did not mean it. If science is responsible, through reason alone, for the twentieth century, with two wars and a depression in only half of it, and with cobalt bombs prepared to spring back at them, and on all of us, scientists ought to feel primal guilt. No doubt some of them do, but they are helpless before their feelings.

In the presence of scientists I feel instinctively superior as a poet. I have announced their limitations in quoting Einstein. I have said above in all fairness that there is no argument between science and art, that imagination works equally in both; yet I feel compelled to say that most poets exalt mankind (sometimes even when condemning it, or satirizing it, or holding it up to ridicule - one may think of Baudelaire, of Swift), that poetry which lasts has perforce moral value, is for the good of man, and that its situation in the depths of consciousness allies it with religious intuitions, and that its ability to speak for the heart as well as for the head gives it a limitless potential power for the shaping of truth.

Men who have lost this vision are be- ginning to see it again. Man cannot live by the bread of executive gain alone, by the bread of factual control over matter, by the proudest boasts of materialism. He must live by inner compulsions, by deep natural drives, by sensitive intuitions, by spiritual realities, by concern with the ineffable, by devotion, by prayer, by humility, by all those dynamic forces which keep the soul alive in struggle and pierce the veil of illusion. Much of this reality may be imbedded in the subconscious. It is from these reaches that art is born and here I am talking of only one art, poetry.

I cannot see that the study of poetry, a serious and a glorious thing from the time of Shakespeare to the time of Dylan Thomas, can harm man and I can see that its moral power can enrich the quality of his life. I thus think that it is valid to study it and to teach it. One writes it if one must.

I OUGHT to end these generalizations on a note about criticism. It may be that the apercu, the unschematized, personal intuition is as good a type as any, maybe better than most or than any.

Students tend to rebel, for instance, at Yeats' hard-won schematization in A Vision which, although fascinating, fails to satisfy due to arbitrariness and straining. Few really love it. Many can admire its conic elaborations but it somehow does not take in all of life while pretending to do so. They give it admiration, along with understanding, but they do not give it love, which it does not invite. It may be that the relatively few, somewhat undisciplined, but thoroughly human and cogent asides, chance perceptions and penetrating remarks made by Robert Frost, whose abundant genius I praise, represent the best criticism about poetry, a criticism not of a school, also not eccentric, but wise flashes of truth thrown off easily, if sparingly, down the decades.

Last spring at Princeton, as an example, Frost said abruptly, "All science is domestic science." That jumped a gap; we relish it. This gives onto one o£ the above arguments. With marked wit and deep wisdom, that is, with a sublime love of truth he related the disinterested men of science, the atom-cobalt dreamers, the earth-shakers, to the man in the street who is the woman in the kitchen and showed that scientists are, after all, only trying as best they may to domesticate the universe. It was a witty, pithy, most humane and lovable statement, at which the crowded house chuckled, and then roared.

We use doing as a kind of escape from being. The scientists are the doers. Business men are doers. What I am really concerned with is being. Poetry is concerned with being. It erects states of being. It is a search for a way to be. We are all trying to be. Science through doing has made us afraid of being. Poetry, as well as the other arts, encourages us in being. Let us not be so burdened with doing that we neglect to see that "Even the thorn bush by the wayside is aflame with the glory of God."

Sir William Haley (center), editor of The London Times, who spoke to the senior class in theGreat Issues course on October 15, is shown with President Dickey and Prof. Robert K. Carr '29,course director, in the Public Affairs Laboratory, Baker Library, where a special display wasdevoted to his world-famous newspaper.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1956 -

Feature

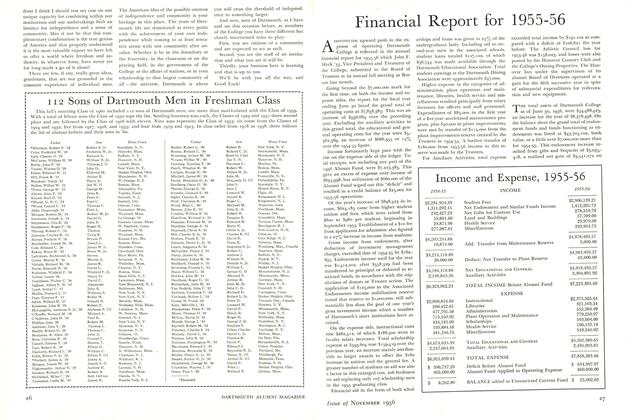

FeatureFinancial Report for 1955-56

November 1956 -

Feature

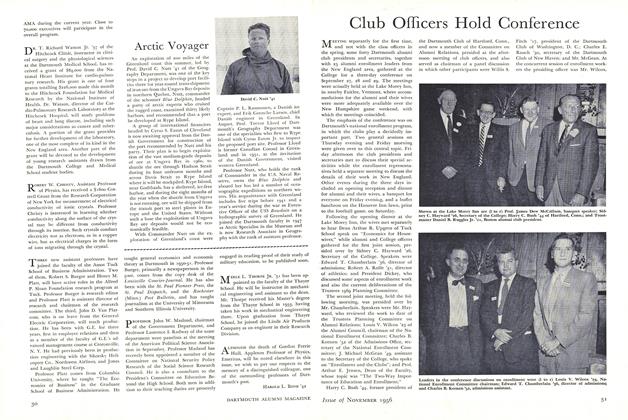

FeatureClub Officers Hold Conference

November 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

November 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

November 1956 By RICHARD C. CAHN, FDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS

RICHARD EBERHART '26

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

April 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

May 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksTHE ISLANDERS.

December 1961 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksSKELETON OF LIGHT.

December 1961 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksDARTMOUTH LYRICS.

NOVEMBER 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26

Features

-

Feature

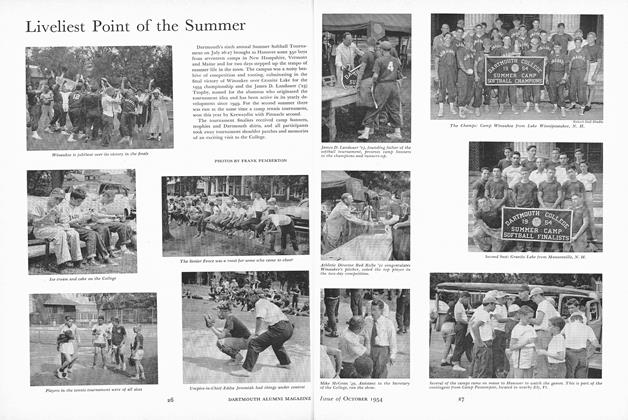

FeatureLiveliest Point of the Summer

October 1954 -

Feature

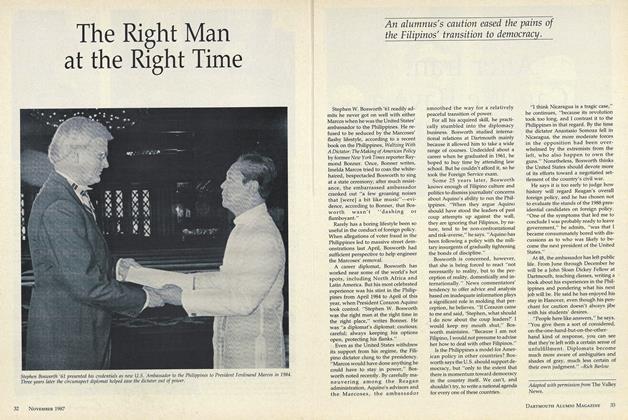

FeatureThe Right Man at the Right Time

NOVEMBER • 1987 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

FEBRUARY 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

JULY 1959 By JOSEPH W. WORTHEN '09 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

DECEMBER • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureA Stimulus to Town Development

MAY 1957 By PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26