By Thomas Vance.Chapel Hill: University of North CarolinaPress, 1961. 56 pp. $3.50.

It is the pain that pricks out the true song, But the joy that guides the notes to melody

writes John Wain, English poet and novelist, in "A Boisterous Poem about Poetry." He also writes in the same poem

Nothing is beautiful until it has reality, And art is the apprehension of the real: Facts are too heavy to hold in the thin tackle of knowledge - Only the muscles of art can lift them to the light.

These lines may serve as pointers toward Thomas Vance's poems.

Vance's Skeleton of Light, his first book of poems, shows him to be highly subjective, deeply speculative, and nervously alive to showers of ideas of his inner concern: how to turn painful knowledge of self and world into works of satisfying objective reality. He is trying to do the impossible, a persistent poetic attempt among poets, in him to arrive even at the imaginary skeleton of light.

Using our Wain text, he gives the impression of being able to write endlessly of the complexities beyond facts, throwing out ideas of rich metaphysical relationships, but he has "muscles of art" to redeem abstractions and reduce them to pleasing orders.

His deep, inward struggle is toward the ethereal; he keeps febrile images and tones coming on and on. He invites the reader to a turbulence, which is expressed with a peculiar originality and style of his own. He is in the heady Shelley camp, rather than in that of the earthier Keats.

"Love's End" is a good example of the psychological type of poem central to his vision. Note lines from various poems. His taste "is mortal yet / mysterious beyond nature." "... silence sings beyond / The sudden daffodil." "Rich weddings give themselves and go." "... vision pierced my blood / with incandescence, then / Failed with the darkening wood." His thrust is toward "the still impossible / The pure transparence at the shadow's heart."

There is the Shelleyan Vance but part of him is earthier, where "muscles of art" rather than skeletons of light produce poems rooted in the objective world. "Striking a Balance" is notable among these, as are two poems after early Swedish ballads, "The Maiden Shrouded as a Deer" and "Kerstin and the Bridegroom," both delightful, yet even these well told tales have metaphysical meanings.

Thomas Vance's intellectual subtlety is more concerned thus far in his writing with advancing communications of labyrinthian interiors of the mind than with extending control to the exterior world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

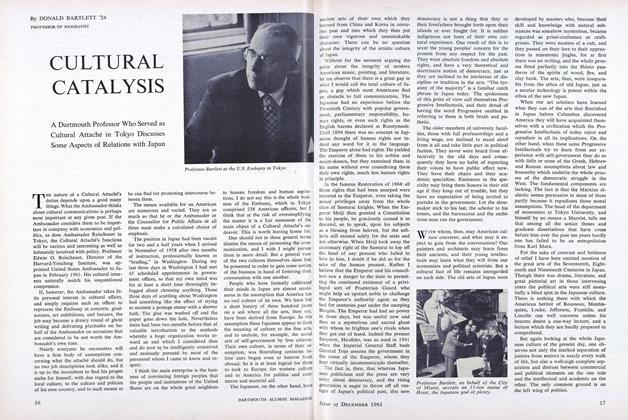

FeatureCULTURAL CATALYSIS

December 1961 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Feature

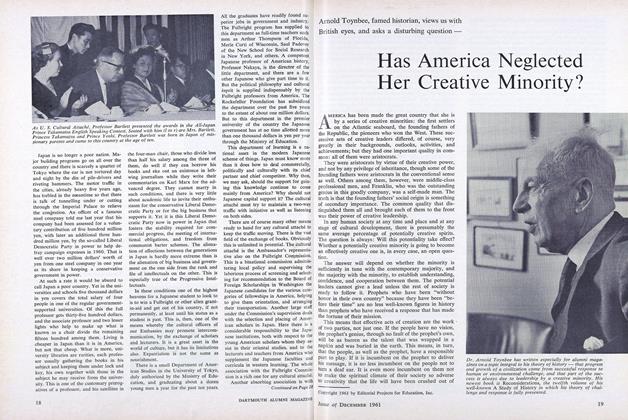

FeatureHas America Neglected Her Creative Minority?

December 1961 -

Feature

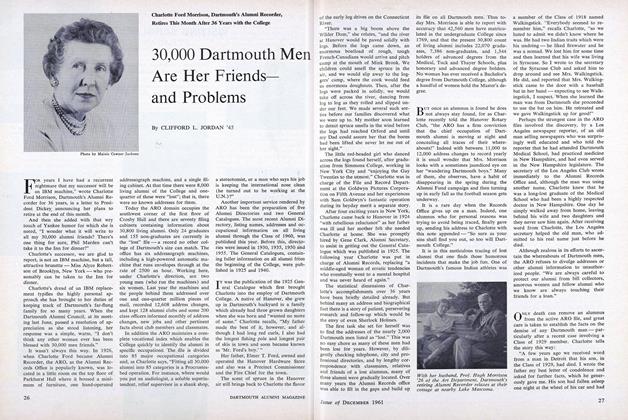

Feature30,000 Dartmouth Men Are Her Friendsand Problems

December 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

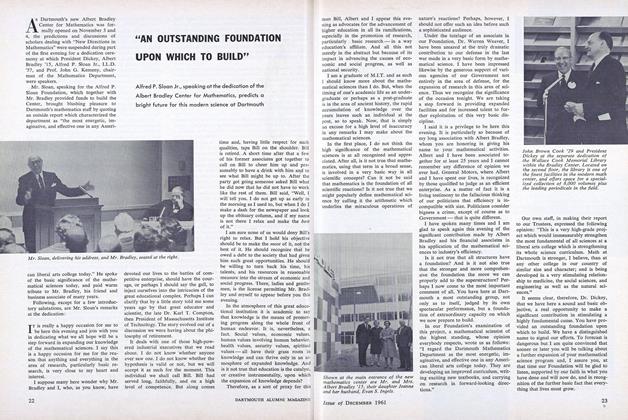

Feature"AN OUTSTANDING FOUNDATION UPON WHICH TO BUILD"

December 1961 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

December 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, JAMES L. FLYNN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1961 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HENRY S. EMBREE, JOHN F. RICH

RICHARD EBERHART '26

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Books

BooksSPUN SEQUENCE.

July 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksDARTMOUTH LYRICS.

NOVEMBER 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

April 1977 By Richard Eberhart '26 -

Books

BooksTalking to Oneself

April 1981 By Richard Eberhart '26

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

May, 1922 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

JUNE 1965 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

FEBRUARY 1970 -

Books

BooksHOGARTH ON HIGH LIFE. THE MARRIAGE A LA MODE SERIES FROM GEORG CHRISTOPH LICHTENBERG'S COMMENTARIES.

DECEMBER 1970 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLOGIC AND SCIENTIFIC METHODS

June 1948 By Maurice Picard -

Books

BooksDizzying Truths

September 1978 By WALTER W. ARNDT