Student enterprise today has no chance to operate as it did when Dartmouth men started "le grand tour" by -

A BIG gang of us left Hanover that June evening and headed for White River Junction to catch the night mail to Montreal. Some had gone on ahead, others would follow, but every one of us had a letter from the Dartmouth Outing Club directed to a man named John Storen down on St. Antoine Street, near the riverfront. We were the cattlemen; extra crew for the ships that carried wild steers raised in the Canadian Northwest across the ocean to England.

That first night was a rough one. To save money we purchased one berth for each two men and when the northbound night mail came chuffing into the Junction in the small hours, with two Moguls on the head end, we stowed ourselves away and tried to go to sleep. In my half of an upper berth I squirmed around and cursed Ed and Ed cursed me and we asked each other what time it was, and where the train was now, and why we had paid money for this miserable little shelf. However, we slept some as the train rumbled up the White River Valley of Vermont, dozing to the rhythm of wheels clacking over the rail joints and the steady beat of the steam locomotives horsing the heavy train over the grades.

The night ended; in the dawn the train raced across the French Flats toward the St. Lawrence, while we gratefully dressed. By breakfast time we were trooping out of St. Bonaventure Station, headed for the Hotel Windsor to set up our base and reconnoitre. At the hotel we managed to save some more money. Two of us hired a large room, and with well-placed tips the chambermaids were persuaded to show us where spare cots and blankets were kept. By careful conserving of space and a couple of extra mattresses on the floor, the room accommodated eight of us.

Our headquarters set up, we held a short conference in the Windsor Tap Room, before starting for the harbor front to find out from John Storen where our ship was and when we sailed. There we had bad news.

Three of us were to ship aboard the Alan Line's Devonian, due to sail at midmorning of the next day and three more were to join White Star's Cornishman, which was to depart by noon at the latest. They were all ordered to report at the Quai Alexandria immediately after breakfast. As for Ed and me, we were assigned to Anchor-Donaldson's Salacia, time of departure unknown. "Just keep in close touch with me," said John Storen, leaning on the counter of his little waterfront shop and scribbling in his big ledger.

Early next morning our room at the Windsor was in an uproar. The lucky six who were to be sailing down the St. Lawrence by dinner time packed their street clothes carefully away and hauled out their ski outfits, which for Dartmouth men of 1925 were mostly clothing purchased from firms that supplied lumber camps. Dressed for the cold voyage across the North Atlantic, they picked up their bags and tramped down to the lobby, and a hard-looking lot they were.

Ed and I dashed after them, rode with them in their taxi to the waterfront and watched them go aboard. Both vessels had taken on their cattle in the early morning hours and were ready to sail, whistles blew, lines were cast off and the ships backed out into the river, headed downstream and were off for England.

Staring until they were out of sight, we stood on the pier wondering how many days we must hang around waiting for our ship to sail. Idly we drifted from one wharf to another, watching the work of the waterfront and at noon we again reported to John Storen's office. He shouted at us as we crossed his threshold.

"Get your gear and get aboard the Salacia," he roared. "Cattle will start running at one o'clock. Hurry, boys, hurry."

We raced back to the Windsor in a taxi and changed into our sea-going outfits. Again the clerk stared wide-eyed at two hard-looking tickets checking out of his hotel, but we tarried for no explanations. We paid and ran, and in another taxi we headed for the Quai Alexandria, shouting at the driver for more speed.

We need not have hurried. Alongside the pier lay the Salacia, deserted, no smoke rising from her single stack, no cattle, no crewmen except a big stoker viewing a huge pile of coal on deck and vehemently expressing himself with obscene British participles. The vessel had no railings. The upright stanchions were in place, but the steel cable that should have been rove through the eyes lay snaking about the deck in rusty confusion. Odd pieces of lumber lay scattered about; flies buzzed around a heap of garbage beside the galley door; her sides and superstructure were marked with big patches of rust like the map of a group of unlovely islands. This was the British Merchant Marine, and we were horrified.

We had not stood long gazing upon this miserable and apparently abandoned tramp steamer when a little gray-headed man with a red nose, a lush mustache and a hatchet came stumping down the pier.

"Are you boys cattlemen?" he queried, when he spied us.

"Yes," I said. "When do we " "Follow me," he ordered, "and hurry."

Hurry? Why? It certainly looked as if tomorrow or next day would be soon enough. But we followed him, along the pier, up a narrow flight of stairs, into a room crowded with men and over to a counter where a clerk presided over a big ledger.

"Ordinary seamen," grunted the little man with the hatchet to the man with the ledger. "These coves are the last two. I've a crew now."

We scratched our names in the big book, rounding out a list of twenty men signed on as extra crew to feed the cattle on the long voyage to the British Isles. The little red nosed man waved his hatchet at the roomful of men.

"Listen. I'm Shorty McConville, cattle foreman. You've signed up for hard work and a free passage to the old country. Only one thing to remember and don't ever forget it. England this day expects every man to do his duty. Now get down to the ship. Cattle will be running any minute now."

Down the deserted pier we tramped with our luggage, aboard the dingy tramp, along the cluttered deck to the stern, where cattlemen stay, a ship's length from the regular crew in the forecastle. While we scrambled for bunks and stowed our dunnage the old Salacia began to come to life. She trembled, the staccato beat of a steam donkey engine on deck boomed through the empty 'tween decks like a bass drum; over and above the hollow rumbling rose the voice of Shorty McConville.

"Lay on deck. Tumble out. The cattle are running. 'England this day expects every man'.

The rest of it was drowned out by the deep-throated whistle of a freight locomotive on the pier not twenty feet from the cabin porthole and the rush of men "tumbling out." We surged through the door of the cabin, clambered up the stern companionway and poured out onto the after deck. Seamen were reeving the wire cables through the eyes of the stanchions so that the ship had railings. From the stack billowed thick, black smoke and from the fire room below came the metallic clang of shovels and slicing bars and slamming furnace doors as the black gang hurried to build up a head of steam. At a 45-degree angle from the foremast hung a boom, a seaman sat at a steam winch and snatched great sling-loads of boxed 90-pound Canadian cheeses from the pier and lowered them into the forward hatch. From the mainmast another boom reached out toward the wharf, another seaman worked the levers, the winch chattered as it swung cargo aboard. Wide metal pipes led from the grain elevator down into the ship; from them came the whispering, rustling, rushing sound of wheat pouring into the hold.

Yet all this activity was background - taken in with a glance. The cattle trains on the pier alongside were our business; long strings of cars loaded with bellowing steers from the plains. Dozens of stevedores - little Frenchmen - manhandled a big gangplank to the door of the first car; they fitted together sections of fence to enclose the narrow cleated runways that led all the way to the lower deck. Then the door of the car slid open, the Frenchmen yelled and poked at the beasts with broomsticks sharpened to a fine point; the steers bellowed some more and began to trot down the gangplank, slipping, sliding, stumbling. Any who hesitated were goaded by men posted along the fenceways; harried and prodded until they moved on into the darkness below decks.

When the last steer in the car had been rounded up by the shouting stevedores and chased down the gangplank, the yard locomotive gave a few puffs and the long line of cattle cars moved ahead a little. Another car door slid open, more wild yelling from the drovers and forty more steers trotted and slid and stumbled down into the Salacia's cattle pens.

Peering through the open hatch at the stream of cattle pouring down the runway, we saw Shorty McConville. And Shorty saw Ed and me.

"You two school boys lay below and git to work," he shouted, "What the bloody hell do you think this is? An excursion boat?"

Suddenly we realized we were alone on deck. While we had watched, fascinated, the other men had gone to work below. Britishers, Scots and Irishmen taking this opportunity for a free summer visit home, they were men of Canada accustomed to such scenes. Without an order, they had turned to the work of tying up the animals, leaving us on deck, staring. We hurried down the companionway into the maelstrom below. Shorty glared at us, waving us toward a pen where Ellis and Paddy struggled with thirty steers milling around inside.

The pens were like horse stalls varying in capacity from an enclosure of a size to hold a single beast to some three times as big as the largest box stall in a millionaire's barn. The pens ranged down the B deck from bow to stern; most of them along the sides of the ship, but some in the center to use advantageously the space not taken up by the fore and after hatchways and the engine and smokestack spaces. Cattle boats were ordinary small ocean-going cargo carriers of five thousand tons and upwards with the. conventional forecastle, forward well deck, amidships structure with pilot house, bridge, officers' quarters and radio shack, then an after well deck and poop or stern castle.

Between the forecastle and the amidships, the well deck was covered with a temporary wooden housing to provide more room for cattle pens. The after well deck was covered over in the same way, so that every spare foot of deck space in the ship was used for cattle.

Every part of both decks was an uproar of shouting men and bellowing steers as the Canadian drovers prodded the stream of cattle into the pens. When each enclosure was full, they slammed the gate, rearranged the fencing and guided the animals into the next empty space. We had no time to watch them; nothing concerned us except the steers milling around in this pen.

Each one had a length of half inch rope about four feet long tied around the base of his horns. Who fastened the ropes to these wild beasts of the plains I never knew, nor did that concern us. Our duty was to catch the loose end dangling between the steer's fore legs, slip it through a hole bored in the horizontal plank across the front of the pen and tie a knot. When we had done this thirty times, we would be ready to move on to the next pen.

The four of us leaned on the belly-high plank gazing at the huddled animals. Paddy turned to me and grinned.

"Well, boy, want to go in there and bring one o' them beasties up front here so I can grab the rope an' tie him up?

I stared at the long-horned steers huddled at the back of the pen. It seemed to me that every one of the thirty were glaring at us, hostile, malevolent, ready, the instant a man ventured anywhere near, to give one quick swing of the head and plunge a two-foot-long, needle-sharp horn into his vitals. Those horns fascinated me. Their whole spread was over four feet, they were like none I had ever seen around New England; more like the horns on some trophy on the wall of a banquet hall. Again I wondered how any mortal man had ever managed to tie a rope around them.

"I'm not blaming you school boys for not doing this," observed Paddy, slipping under the horizontal head plank. "This you can learn from no book."

With a quick motion he had one of the steers by the nose, fingers up both nostrils. With his right hand he had the beast's tail and he commenced to wind it with a crank-like motion. With tremendous bellows the animal edged to the front of the pen, with Paddy's iron grip on the nose guiding him and his strong tail twisting furnishing the motive power.

Reaching under the head board, I seized the dangling rope, slipped it through the hole and tied a knot. This steer was secure. Then Paddy reached for another animal, and Ellis, who had lived for years in Alberta, started working at the other end of the pen, bringing them up to the head board so Ed could reach the rope and tie the knot.

This sort of thing went on and on. Up and down the decks our team ranged, with Paddy and Ellis doing the tail twisting, while Ed and I tied them up. Sometimes we saw other groups near us; but often we seemed to be alone in these murky decks, endlessly struggling with steers, always looking ahead and more to be done.

And then we suddenly discovered it was accomplished; 635 beeves were securely fastened in their pens. During it all, Shorty McConville was up and down the decks, exhorting, advising, occasionally laying down his hatchet to assist with a difficult one. When he saw all his cattle safely in place, he produced a half a dozen hatchets from a bag and with appropriate remarks as to what England this day expected, he conferred them upon the six most likely looking of his men. This made them foremen of a particular section of the deck and the rest of us were briefly instructed as to the proper attitude toward our superiors.

The hatchets were to chop the wires on the bales of hay, as well as serving as the insignia of office. We gave the cattle plenty of hay and a measure of grain, we watered them and bedded them down with straw. Somewhere along in here we heard shouting on deck, and short bursts of action from the steam winches. The ship trembled and shook, from amidships we heard the slow rhythmic beat of the reciprocating steam engine - a three-cylinder triple expansion job. Moving further aft we could feel the motion of the propeller shaft and the steady muffled thump of the Salacia's single screw. We were under way; we had not been on deck to witness the scene of departure. But it did not matter. There had been no one on the pier to wave to us.

WHEN at last all the cattle were fed we were allowed to go on deck and look around. Far astern, silhouetted against the June sunset, lay the skyline of Montreal, the Sun Life Building, the church spires, the rectangular bulk of the grain elevators along the river front, all very small in the distance. We were in the middle of the broad St. Lawrence; the distant banks were verdant green, dotted here and there by white farmhouses and occasionally one of the villages of French Canada with its big church looming above the close clustered buildings.

We sent two men to the galley amidships and before long they returned with two buckets containing our supper and a big kettle of tea. In the dusk we sat on the poop deck eating from the tin plates issued to us, watching the St. Lawrence widen into La© St. Pierre. Seamen rigged hoses, the ship's pumps started filling the huge tanks with enough lake water to last over six hundred cattle for ten days to two weeks. For a while we watched the foaming, wake of the ship; a line in the placid waters of the lake reaching far astern toward the last glow of the setting sun. Then we lay below and turned in.

The Anchor Donaldson Line, in conformity with British Merchant Marine regulations, did well by us. The bunks were boxes, coffin size, a bit more shallow, and, of course, no lid. A mattress of fresh straw in clean new gunny sacking lay neatly fitted into each bunk. These mattresses, we. learned, were burned after, one roundtrip to Britain; a measure which greatly reduced the normal vermin population of a ship's cabin. A few of us were fortunate enough to have small straw pillows and we each drew two blankets apiece, redolent with carbolic acid odor, but clean. So we took off our hats and our shoes and tumbled in. Beyond the cabin door lay the first of a long line of steers that reached to the bow, beneath, us the steady beat of the propeller, and a rushing, churning sound as the blades bit deep into the waters of the St. Lawrence. We soon slept.

In the gray dawn we were awakened by Smittie, a little Cockney selected from our group to be night watchman. Through the hours of darkness he had trudged up and down the dimly lit aisles between the pens of sleeping steers. His orders were to turn out the cattle crew if anything went wrong, and at 4:30 to get a kettle of coffee from the galley and rout the men out of their bunks.

Smittie executed his orders. Nothing wrong during the night out among the pens, so he had to bother no one. As for waking up the cattle crew, he could have done it in the immemorial usage of the sea with wild shouts, lush profanity and tremendous poundings on the bulkheads. But Smittie had put in years in the employ of a fine London hotel.

"Time to get up, sir." I felt some one gently shaking my arm.

"Coffee's 'ot and on the tyble, sir."

As soon as I sat up and yawned, he moved on to the next bunk to wake up die next gentleman. By the time we had put on our hats and our shoes and gath- ered around the cabin table with our tin cups we heard Shorty McConville descending the after companionway, shouting as he came.

"Up, you beggars. Tumble out. Hit the deck. Rise and shine. There's cattle to be fed."

He barged through the cabin door, flourishing his hatchet.

"Swill that bloody coffee and get out there on the decks. This ain't no excursion steamer. England this day expects..."

In the gray dawn light every man did his duty; we forked hay and lugged water until all 600-odd animals were fed. Then we sent a man to the galley to bring back our breakfast - a two-course affair; oatmeal in one bucket, pancakes in the other. The Salacia was passing Quebec as we ate, sitting on the after hatch. Above us loomed the great steel bridge over the river and we stared at that awful middle span that fell so many years ago as they were trying to fasten it into place and carried a whole construction crew to death in the waters a hundred feet below.

The morning we spent hoisting bales of hay from the forward hatch with a block and tackle and manpower; no steam winch for this job. After that we fed the cattle again and ate our dinner and cleaned the aisles between the pens and lugged water and fed the beasts their supper and got our supper from the galley and ate all of it that was fit to eat and hove the rest over the side. The shores of the great river ever widened as the Salacia's engine steadily beat out her thirteen knots, black smoke poured from the stack and cinders were gritty under foot on the after deck. A long wake trailed astern; ahead the eastern sky darkened - sundown was not far away.

At dawn we had been off Quebec - the head of tidewater. We had steamed down river through all the hours of daylight of a long June day and now we made ready to drop the pilot. The engines stopped, the ship waited for the little pilot-boat making out from Father Point. When he had gone over the side and his boat had cleared away, the Solatia's engine again started its slow beat, the thump of the screw made our cabin tremble and shake, but it was a rhythm to help tired men sleep. We tumbled into our bunks; soon we were snoring, but in the few minutes before I dropped off I could feel under me the long heave of the ocean swells as the ship headed out into the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The next day was straight seafaring out of sight of land; pitching, rolling, spray over the bows and a wildly racing, vibrating, screw as she put her nose into it; then, as the stern settled and the bow pointed upward, the slow steady stroke of a propeller biting water, thrusting ahead. In this seaway men were sick and beasts were sick. The men had the better of it; they need only be sure it was the lee rail they leaned over. But beef creatures are not made so they may quickly be rid of whatever sets heavy on the stomach. They lay moaning, eating nothing, too miserable to eat or drink or move.

THE day we crossed the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the ship was full of rumor and speculation. Were we to go south of Newfoundland, through the Cabot Strait, leaving Nova Scotia's Cape Breton starboard? Or had the ice cleared sufficiently from the Strait of Belle Isle so the Salacia might take this narrow passage between the Labrador and the northernmost reaches of Newfoundland? For less than three months in summer this route, saving a day, is available to shipping. The rest of the year it is choked with ice floes and bergs, unsafe for any vessel but an icebreaker or a government cutter.

We went to bed still guessing, but by the time Smittie brought the morning coffee and waked us, we knew.

"We're in Belle Isle," he whispered. We tumbled out and raced up the companionway for a look. We saw nothing; the fog walled us in, thick white, cold and clammy - so heavy we could not see the bow and the smokestack amidships was but a dim and vague shape. The tempo of the steadily thumping propeller slowed down now to the cautious, timid beat of half-speed; every man of us felt as if we were shuffling through a dark room, feeling ahead lest we slam into a solid object. The Salacia's whistle sounded; then, from far away in the fog came the bass tones of another vessel's whistle, and, from a different quarter a third ship's warning, and then a fourth, from ahead.

By noon the fog was burning off, the sky lightened, through the mist the sun showed vaguely, no brighter than an old tin plate. In minutes the fog was gone; miles to the northward lay the bold shores of the Labrador - bleak, cold and forbidding. To the south lay Newfoundland's northern shore, a pleasant place of green fields and little white houses shining in the sun.

It was cold in Belle Isle. When we turned in, not long after eight, some of the old hands said we were near an iceberg. From the deck we had not been able to see it, but a numbing chill penetrated everything. The two thin blankets Anchor-Donaldson had issued to us were not enough, even though we lay in our bunks fully clothed, with our hats on.

"I've had a bloody 'nuff of this," announced old Timmins, swinging his legs out of his bunk. "I'm going to see the bleedin' engineer and get some steam."

The engineer, - too, must have felt the nearby presence of the bergs, for he made no argument and the steam pipes in our cabin were snapping and sizzling before Timmins returned. Cozily warm, we fell asleep to the beat of the ship's propeller thumping steadily beneath us. By the dawn, when we were turned out to commence feeding our cattle, we were in open sea.

Now every day was like every other day; an unbroken expanse of water, far horizons and near-at-hand problems. The work was hard and monotonous; an endless purveying of hay, grain and water to the steers.

Sometimes I have wondered how many hundred tons of fodder we put in front of those 635 cattle. We hoisted the bales of hay from the forward hold, rolled them down the deck, chopped the baling wire with our hatchets and then went to work with our pitchforks. Each bale weighed as much as a man, each sack of grain nearly as much. Occasionally we tried to sneak a little rest, but Shorty McConville kept an eye on us all and no man could sit down, or lie down for long without being told what England this day expected.

As many times as I have told of these days of hard farm labor aboard the ship Salacia, never yet has any one failed to ask me what we did with the manure. This invariable question may be the result of the American passion for cleanliness, or possibly where so many are interested in gardens, there was a thought of such vast quantities of fertilizer idle aboard one tramp steamer. The answer is that we did nothing about this detail. Our duties con- sisted only in laying food before these animals, watering them, and seeing to their straw bedding. Fortunate that this was so, for we always tumbled into our bunks, exhausted, not long after supper. We had not time or strength for further duties. Although our cabin door opened directly upon one of the rows of cattle pens and the nearest big bullock lay not two feet from our door, we never noticed any odor. Clean sea air, always moving down the big canvas ventilators and along the lower decks, took good care of that.

The food was fair; only occasionally was it so bad that we hove it over the lee rail. At Dartmouth Ed and I had attended an informal lecture for those who were planning to make "le grand tour" of Europe and there was special advice for those of us who were to be cattlemen. We were instructed to have in our sea bags some emergency rations to use when the cook issued a bad meal. A bottle of ketchup was recommended. This, we were told, was to use whenever the cook allowed British ideas of seasoning food to run away with him, or on occasions when he was too busy to use any seasoning at all. The ketchup bottle did a lot for us.

On Thursdays and Sundays we had sailor's plum duff and the Salacia's cook did a wonderful job with it. We were each entitled to one square of it and the cook, wise from years of experience at sea, counted off the exact number before he handed the pan to our man at the galley door. Thus he avoided a fight in the cabin as to who would get an extra piece.

The crew were a good-natured lot. Happily, we had no one who felt he had to show what a manly fellow he was. One thought was always uppermost in their minds: they were going "home" after a long, long stay in Canada, home for a short visit in the old country, a time when they would be with mother and father and the rest of the family, boyhood friends. They would drop in for a beer at the pub and be accepted as an authority on what it is like on the plains of Saskatchewan or in the mines of Ontario. They talked constantly of what they would do when they got home, of how they missed it and of hard Canadian winter weather and how they hated it. Yet all except one planned to return to Canada before summer's end.

AFTER taking our departure from Labrador's dark rocky coast, at Belle Isle, we were seven days on the high seas. The sameness of the days made us feel as if we had been at sea as long as we could remember; feeding cattle, hoisting hay from the hold, cutting baling wire with our hatchets, eating, sleeping, looking forward to the day we had plum duff.

I was physician for the cattlemen. My uncle, a doctor, had presented me with a little leather case containing medicines and I had added to my supply in Montreal. For a cold, I dispensed aconite pills, for mal de mer I handed out Mother Sill's Seasick Remedy and I did some bandaging of cuts, using my iodine bottle freely. I had a small box of licorice powder, a good old remedy for what today is known as a torpid colon and the patients who came to me for this complaint were the most appreciative of all. Before the end of the passage my little box was empty and so, too, were the grateful patients.

"The Irish pilots," said Timmins one night, pointing at the gulls circling about the ship. "We'll see land in the morning."

Land in the morning; the entire cattle crew brightened up and commenced babbling about what they planned to do ashore, as if they were aboard a whaler returning from a year's voyage. And Timmins' prediction was accurate. When Smittie routed us out in the dawn, instead of yawning and grousing over our coffee, we raced up the stern companionway to see where we were. There it was: Ireland - low green hills to starboard.

All morning we followed the Irish coastline and by noontime we sighted, dead ahead, a strange little island with sheer rock sides and a green tufted cap of verdure on top. Paddy's Milestone, this is, standing at the mouth of the Firth of Clyde, the last land the Irish immigrant sees as he sails out of Glasgow, bound for the New World.

Now the big cargo booms were unshipped, steam hissed in the pipes leading to the winches, and crewmen took their places at the control levers. A cattle owner is allowed free carriage of a fourteen days' supply of hay and grain for his steers and we had made it in ten, so up from the hold came the surplus. This time we did not mind the work; steam did the hoisting and all we had to do was roll the bales along the decks and leave them where they could easily be unloaded in port.

The Firth narrowed, we were nearing the river itself, a narrow stream carrying a tremendous water-borne commerce. Two little paddle-wheel tugs came out to meet us; one took a line ahead, the other a line astern to keep the Salacia steady so she would not swing into one of the nearby muddy banks. Throughout the late afternoon, at half speed, the vessel felt its way up river, past farms and fishing villages, then towns and shipyards and the outskirts of Glasgow itself. It was ten o'clock and the long Scottish twilight was fading when at last the laboring, splashing tugs eased our ship up to Brumelagh Pier.

A crowd of fellows in long white butchers' coats swarmed aboard, untied our cattle and drove them out on to the pier, the whole business taking a surprisingly short time. Or perhaps it was only that it seemed short to us, for now we were only spectators. Leaning on the ship's rail we idly gazed at these men who now had the responsibility of herding over six hundred wild steers to their next destination. It was nothing to us, our work was done; if one of them got loose or gored a man, it would not be our man who was carried off on a litter. Yet these big Scotsmen did not have half the trouble the little Frenchmen had loading the cattle at Montreal, or that we had tying them up as the ship sailed down the St. Lawrence. These steers were tamer now, chastened by ten days in the pens of the Salacia - the ordeal of trying to keep their feet on a ship that pitched and rolled to the swells of the North Atlantic. Their legs were weak from ten days with little use and they had been seasick. They trotted meekly off and that was the last we saw of them.

THE tugs shifted us to a nearby pier and we slept in a strangely quiet ship; no beat of the propeller beneath us, no creaking of cabin timbers in a seaway; no bellow of steers from the cattle decks; no yelps from Shorty McConville, our foreman. In the dawn we were still slumbering, Smittie, the night watchman in his bunk, too, for a patrol of the pens was no longer necessary. We arose at a gentleman's hour and enjoyed a leisurely breakfast, sitting around the table and discussing our plans.

Then a new uproar commenced.

A hundred men carrying shovels and hoes and brooms came tramping up the gang plank, every one of them wearing a curious arrangement of gunnysacking tied with crisscross thongs to protect his legs from the knee down. This they needed for their mission was Operation Manure. The cranes on the pier alongside lowered enormous iron buckets, six feet in diameter, and into these went everything. They dumped the huge buckets into a dozen coal cars of the Caledonian Railway, the four-wheel, ten-ton-capacity type.

By mid-morning the ship was clean, the cars were on their way to Anchor-Donaldson's farm and the hundred Scotsmen had departed, leaving us alone with the beadyeyed British Immigration officer who was examining our papers. When it came my turn I had trouble signing, so stiff were my fingers from ten days with pitchforks and hatchets and hauling on ropes. He compared the signature on my entry permit with that on my passport, sighed deeply, studied the photograph, scrutinized my features, and at last committed His Majesty's Government to letting me wander about Britain for a while, although plainly he was uneasy about it.

So we were ashore with a pocketful of money, not a large pocketful, but enough to do the grand tour of Europe if we did everything the economical way. Scorning any guide book, we did Britain and the Continent with only a ten-cent map and our own recollection of what we had heard one should see. The place is well posted, we found, and we missed little.

In that summer midway through what people now call the Roaring Twenties, the boulevards of Europe's capitals were like the main street of one's home town in that one might expect to meet a friend at any time. In Bruxelles we met three more Dartmouth men and spent the day sauntering through museums and palaces, pausing after each visit at a sidewalk café to discuss what we had learned. In Paris, walking down the Boulevard des Italiens, of an evening, we met several groups of fellow students. When we inspected Harry's New York Bar, The Moulin Rouge and the Folies Bergeres, others from Hanover were there, absorbing atmosphere.

By mid-August we had seen it all, or thought we had. In quaint little hotels and pensions from Scotland to the Alps we had eaten queer food, talked with odd proprietors and fought an occasional unsuccessful battle with bedbugs. Now if anyone talked about the Rhine or the Venus de Milo or Oxford University, we could immediately join in the conversation. We were full of sight-seeing, tired and broke; so we whirled through England on the Bristol Express of the Great Western, to get our free ride home on a Montreal-bound cattle steamer.

We came back on the Parthenia, a sister of the Salacia. The cabin was full of re- turning cattlemen, but none of the Salacia's men was aboard. This ship seemed dead. It was the cattle we missed, the life and vitality of the two decks loaded with beasts which ate and drank and slept and bellowed and smelled and needed our attention. The empty pens did not seem right; the vessel was not a day from port before we wished we once more were pitching hay and lugging grain. But there was no cargo needing attention. The Parthenia carried Welsh coal and a hundred tons of English crockery - enough, we figured, to put an appropriate receptacle under every farmer's bed from Toronto to Saskatoon.

So we read and played cards and talked with the other homeward bound cattlemen. After tedious days, we awoke one morning to the long, deep, musical notes of the whistle of a Canadian Pacific steam locomotive working a freight drag along the river bank. A man's engine, this; so different from any little European peanut stand with its shrill piping whistle. It sounded mighty good to us.

The author, in rope-suspendered workingclothes, aboard the cattle boat "Salacia."

A 1925 "Jacko" cartoon, by Ray Ring '27, gives a fanciful picture of what the cattle boat trip to Europe was like.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAUTOMATION

February 1956 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

February 1956 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

February 1956 By THOMAS E. BYRNE, PAUL MERRIKEN

Features

-

Cover Story

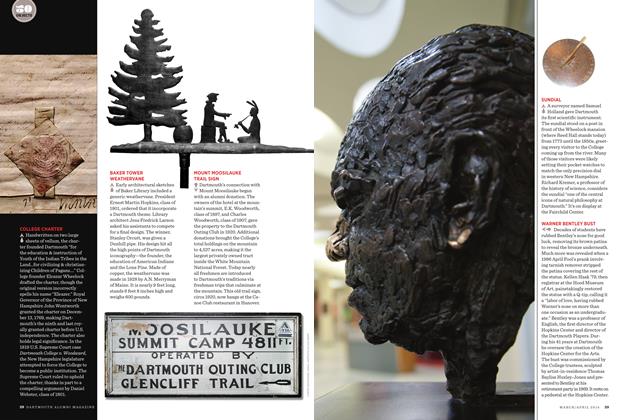

Cover StoryCOLLEGE CHARTER

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Feature

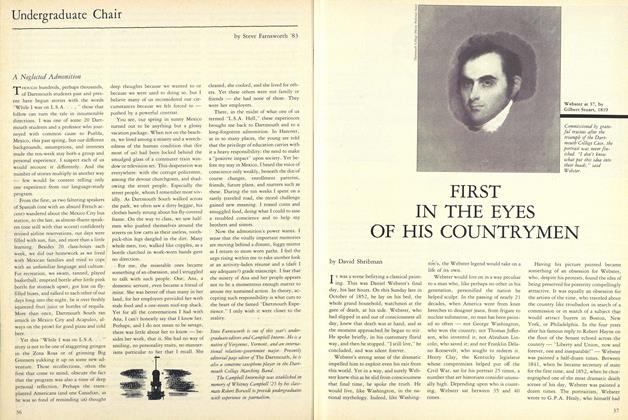

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

SEPTEMBER 1982 By David Shribman -

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Cover Story

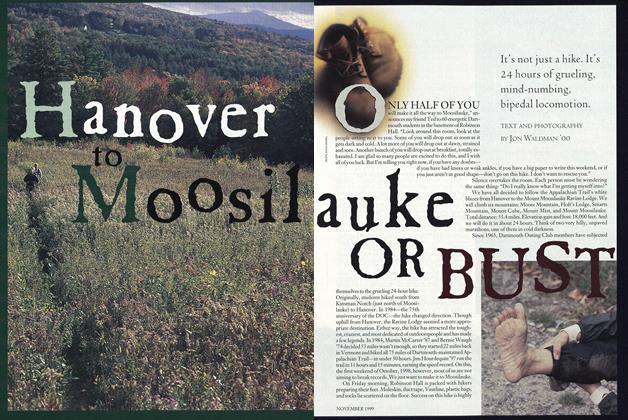

Cover StoryHanover to Moosilauke or Bust

NOVEMBER 1999 By Jon Waldman ’00