THE GODS THAT MADE NEW Hampshire, having served their apprenticeship in carving out the lesser peaks to the east, decided, before slanting down to the Connecticut, to fashion a final masterpiece to demonstrate once and for all what a White Mountain should be.

HEIGHT FOR STARTERS over 4,800 feet worth, placing an alpine summit in the clouds. Shape bold and dominant, with a six-mile axis all to itself. View wide and distant to every point on the compass. Treeline a broad one, fringed by krummholz, with those lichen-covered boulders that give the Whites their characteristically rough-hewn, unfinished feel. Ghosts friendly ones mostly, with the ruins of a summit house, a restored carriage road, the aura of long human involvement and wonder. Weather—brutal enough to complain about having to face and take pride in the facing. Slides great deep ones, unmistakable from afar, lying aslant the mountain like proud check marks the gods made in finishing it off.

Moosilauke, by any measure, is the classic White Mountain, the one you would steer your friends to if they had time to explore just one New Hampshire summit. Even the name contributes to the allure, sounding as it does like a reference from Longfellow or the name of a Swiss breakfast cereal, and yet perfectly appropriate. You couldn't imagine something so large and massive being called Deerilauke, or for that matter, Moosi less. Accessible enough that you can be on it, engaged with it, immediately, situated in a part of the Whites not yet spoiled by the tides of commerce, protected by wise stewardship, devoted to learning as much as to enjoyment, Moosilauke more than any other mountain in New England is a mountain for all ages a mountain to hurl your youth against, to measure your maturity upon, and, for those whom the mountain gods favor, to recapture that youth again in a final valedictory climb.

It's youth and maturity this time parents and kids teaming up for a hike along the Gorge Brook Trail on the last day of a cold, wet July whose passing no one will regret. The dampness is so pervasive it seems to be generated from the rocks, oozing up rather than down; in an ironic kind of turnabout, the brook seems, in its happy flashing, the driest place in sight. I've always been lucky with the weather on Moosilauke, have bored my kids with my own lavish descriptions of the views that await us on top. It's a bit difficult to switch gears, assure everyone that fog, mystery, and coziness are among the most satisfying of the mountain's virtues. We've decided to hike an hour, take an M&M break, reevaluate the weather conditions, then take a family vote up or down.

At least a good, solid part of our trip is already behind us. We've spent the night at the DOC's Ravine Lodge, which is to say safely within the welcoming heart of the Moosilauke experience. For the lodge seems inhabited by the same classic spirit of which the mountain partakes; you get the feeling, seeing the giant ridge pole, the unshakable rafters, sensing the many lives that have found shelter here during its 60 years of life, that this is the precise shape and form the mountain would take on if it wished to reconstitute itself as a base lodge. This is satisfying, but hardly surprising. The spruce logs that frame it were hewn on the mountainside; the wood that burns in the massive fireplace is salvaged off its slopes; the boot soles that have weathered and smoothed the floor have themselves been weathered and smoothed by the mountain's schist.

Away from the Ravine Lodge, Gorge Brook is as gentle a lead-in to the mountain as any, but as usual it takes a good stretch of walking before I shift from second gear to third. It's a quirk of these New Hampshire mountains that each seems to exert its own brand of gravity, and there's a wide variation depending on which one you happen to be on. Cardigan, a few ridges to the south, seems hardly to exert any gravity at all a quick rush and you're there on the open summit. Tripyramid, over to the eastward, seems to exert a gravity ten times that of earth; it's a trudge

worthy of Sisyphus. Moosilauke's gravity seems to lie in the upper part of the middle range; yes, your heart, lungs, and legs know they're up against a mountain, gravity's telling you this with each new step. But the mountain is willing to yield gracefully when confronted with a decent expenditure of energy. In similar fashion, gravity seems shaped differently over Moosilauke than any other White Mountain peak. It creates a different endomorphy, a different style of force not just a vertical pull, drawing intimately inwards, but a pulling extrovertedly outwards as well, an irresistible tug that can be felt on clear days as far away as the Upper Valley (where tire sight of snow on the distant summit is always the first sign of winter and the last), and even farther, transforming itself, through a fine atmospheric trick, into a force composed of the memories of those who knew it in their younger days and are drawn continually back, in recollection often, in person when they can. Sloppy physics, but, coming from one who has spent a lot of time walking these hills, the hard pragmatic truth.

I KNOW MOST OF THEM NOW, the Moosilauke trails. The Glencliff trail starting near the old TB sanitarium then winding through those high overgrown pastures that speak so eloquently of the old self-sufficient mountain life, intersecting, after a good, stiff climb, the Carriage Road, which speaks in turn of the genteel and gently adventurous tourists who flocked to the Whites in the years after the Civil War. The Beaver Brook trail, steep as steep can be, passing up, around, and through what in White Mountain parlance is always referred to as cascades. The Hurricane Trail, which I badly underestimated one October afternoon, and so almost spent a night out in the woods, realizing I was back in civilization only when my boots stumbled into the soft yielding flank of a sleeping cow. The old ski trails, reminders of the time when Moosilauke was the center of Northeast skiing a heritage that is now being exuberantly rediscovered by the telemarkers and those disdaining chairlifts as effete.

Spend much time on the mountain and you realize these are not the only trails, either, not if you define the term to include definite paths or channels, literal and metaphoric both. The watersheds, for instance, the various flowages that make just a few square rods of mountain a generator of rivers. Lost River, the Wild Ammonoosuc, Tunnel and Oliverian brooks, and of course the Baker, flowing past the Ravine Lodge, boulder-hopping down which to Warren being, for my money, one of the giddiest, happiest hikes the mountain offers.

And still more trails in the larger sense, connections made in the memories of the mountain's devoted fans. I think of my neighbor Tim Caldwell 76, Olympic skier, remembering with a rueful shake of his head the infamous late-October ritual of the ski team's ran up to the summit. Or Lyme's Kevin Peterson '82, trail-builder extraordinaire, recalling the October weekend when the remnants of Hurricane Hugo struck the mountain, and a tropical rain on Saturday turned into a midwinter snowstorm on Sunday. Or my friend Syd Lea, poet and essayist, nostalgically rubbing his shoulders as he remembers carrying successive children to the summit on his back.

godparents of Moosilauke skiing; Ross McKenney, builder of the Ravine Lodge and for decades the personification of Dartmouth outdoors; ski coach A1 Merrill, who did so much to resurrect the lodge when it fell into disrepair during the seventies; Put Blodgett '53, restorer of the Carriage Road, worthy successor to those men and women who have worked so hard to protect the mountain in years past. Trails, too, in the names of those who have become Moosilauke legends over the years. J.H. Huntington and A.F. Clough, pioneering meteorologists, spending a winter of research on the summit in 1870; Ira Whitcher of Warren, a homegrown lumber baron; Sherman Adams '20, DOC president and logger; Ford '33 and Peggy Sayre,

And then there are the paper trails found in dusty secondhand bookstores, the library shelves of the Ravine Lodge, mildewed copies of Appalachia, well-thumbed AMC guides from years past, the mountain of good/bad verse Moosilauke has always generated ("Moosilauke! Moosilauke! Mountain sagamore! Thy brow/The wide hill-splendor circles!") Beside me as I write is The History of Warren; a Mountain Hamlet Located Among the White Hills of New Hampshire, by one William Little, class of 1859, with Moosilauke rising in bold and open prominence on the cover above a neat nineteenth-century village. So fresh is Mr. Little's prose, so vigorous its atmosphere of thriving life, that reading it is very much like climbing the mountain itself, only with the added dimension of time, the effect being of plunging through a thicket and coming out in the open of Moosilauke circa 1854.

"Reader, (begins a chapter called "On a Delectable Visit to Moosehillock and What Can Be Seen There the Weather Permitting") let us go on to Moosehillock. The Indians called it Moosilauke from mosi, bald, and anke, place 'Baldplace.' There has been a great storm, but it has cleared off now. We cross Berry Brook where Samuel Knight had a fight with a bear, pass a remarkable flume in the rocks where McCarter was said to be hid when he was murdered....The forest is deep and dark. Deer yard in these woods every winter; bears prowl all summer along, and it washere that Joseph Patch, his son, and Captain Flanders killed the last moose that was ever found in this region....Halfa mile further on and we are at the Prospect House on the bald summit. Chase Whitcher, the first- white settler, thought it a cold place. But Mrs. Daniel Patch, the first white woman who ever stood upon this summit, thought it quite pleasant. She brought her tea-pot with her and made herself a good cup of tea over afire kindled from the hackmatacks."

There is much in Mr. Little's history about witchesand Moosilauke has always attracted its share of these otherworldly erworldly spirits, including the notorious Doc Benton, he of the ungodly R&D. It's worth recalling that Robert Frost, class of 1896, a genius when it came to nuance of place, made his "Pauper Witch of Grafton County" a Warren resident, letting her brag about the secret sights and signs she knows on the mountain: "And I don't mean just skulls of Rogers Rangers/On Moosilauke, but woman signs to man.

Two things are obvious reading all these. First, that perhaps only Washington among the Whites has a richer and more extensive literature than Moosilauke, such a long history of human engagement. Second, that there has always been a definite if undefined sense of mystery about the mountain, strange events which have long since been distorted and enhanced by fiction, which accounts for one of Moosilauke's other defining traits: that wonderful gravity, not just the physical pull this time, but the kind my dictionary defines not only as "solemnity or earnestness of manner" but "the quality of danger or menace as well."

OUR LONG BREAK AT the Ross McKenney monument has paid dividends: the sky is just light enough now that we're persuaded to continue on. After a good fast stretch of walking, the hardwoods begin looking a little scrappy, and as always my legs feel stronger the thinner the trees become, to the point where, encountering the first stunted firs, my joints feel positively reborn. Every hiker in the Whites knows this feeling, the intoxication that comes when the trees drop away and you're suddenly out into another world altogether, as the mountain that s been there all along, albeit subtly, almost invisibly, becomes the naked and inescapable fact. ,

Above treeline, in a landscape that can only be described in these conditions as hypothermia-actic, the fog widens from gray-gray to gray-yellow; it's obvious the sun is up there, but equally obvious that, at least for today, it's no match for the mountain s introspective funk. I drop behind the others to search for some of those mountain cranberries that used to form a welcome if sour addition to Summit House dinners, and when I catch up again with the rest of my family, each of them is wrapped and enlarged by a halo of mist, mythic in their own light now as they wind back and forth along the ridge to the summit proper.

There's no view today, nothing besides the rums of the old Summit House (the burning down of which, in a thunderstorm inside a fog in the autumn of 1942, remains one of the mountain's oddest mysteries) and the usual jumbled collection of rocks. Me, I've been up here before when the outlook is spectacular, and so I'm pointing in all directions as if the fog were transparent, pointing out invisible wonders.

But here, let Mr. Little take up the description, with his glorious joi de view.

"Nearest the north-east is Mt. Kinsman, theprofile moun tain, and above and over it is Mt. Lafayette, its sides scarred and jagged where a hundred torrents pour down in spring. Just to therightisMt. Washington, dome shaped andhigher than all the rest. A little to the south is Carrigain, black and sombre, symmetrical and beautiful; the eyes turn away to turn to it again and again. Forty ponds and lakes are sparkling under the setting sun; the Pemigewassett, the Ammonoosuc, the Connecticut, from their wooded valleys are flashing. To the southwest is Ascutney and wheeling north and directly west is Camel's Hump, and then beyond are counted nine sharp peaks of the Adirondacks. In the northeast is Jay Peak and to the right of it a hundred summits rising from the tableland of Canada...Moosilauke's view is the most magnificent to be had on this side of the continent, far surpassing that from any other great peak in New England because of its isolated position and its great height, and no other mountain near to hide the prospect."

Magnificent in 1854 and magnificent today though my kids will have to take this temporarily on faith. Still, if anything, they can sense the brooding presence of Moosilauke more when it's shrouded in clouds than they can when it's clear and open. All through our hike I've been trying to identify what makes Moosilauke unique, and, looking through their eyes, I think I have it now: its sense of isolation. No, not isolation, self-containment. Mountains merge into mountains in the Whites, steep slopes blend into soft, so they rise and fall in indiscriminate bunches—and yet Moosilauke stands unadulter ated and alone, purely itself, among the largest tracts of New Hampshire land that you can truthfully identify as this mountain and this mountain alone.

BUILT IN I 938, THE RAVINE LODGE (ABOVE) MAKES A BASE FOR FRESHMAN TRIPS. A FOOTBRIDGE ACROSS THE BAKER RIVER (RIGHT) LEADS HIKERS INTO THICK STANDS OF BALSAM (PRECEDING PAGES)

Doc BENTON'S TORMENTED GHOST HAUNTS TRAILLESS MT. BLUE (LEFT) JUST NORTH OF SUMMIT. GORGE BROOK TRAIL (ABOVE), HOME OF THE ANNUAL SKI-TEAM RUN, FALLS OFF TO THE EAST.

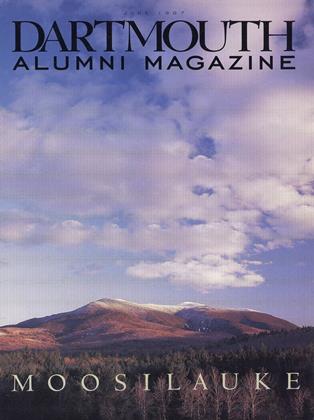

MOOSILAUKE'S 30 SQUARE MILES OF MOUNTAIN RISE TO A BARREN 4,802-FOOT ELEVATION (ABOVE) FRIGID HEADWATERS OF THE BAKER (RIGHT) SCULPT GRANITE BEFORE RUSHING DOWN TO WARREN.

Novelist W.D. WETHERELL'S books include Chekhov's Sister andWherever'That Great Heart May Be. His essays on the Connecticut River and Smarts Mountain have appeared in previous issues of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

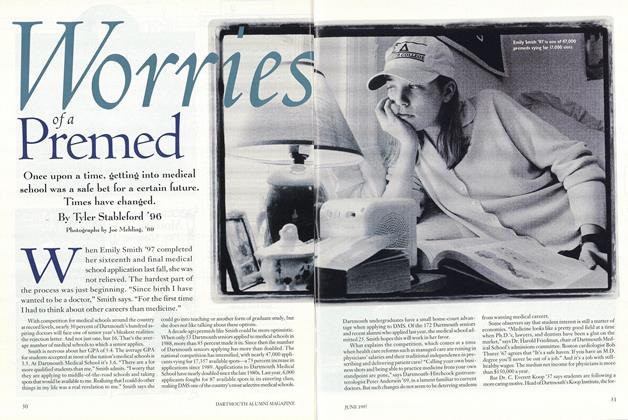

Cover StoryWorries of a Premed

June 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

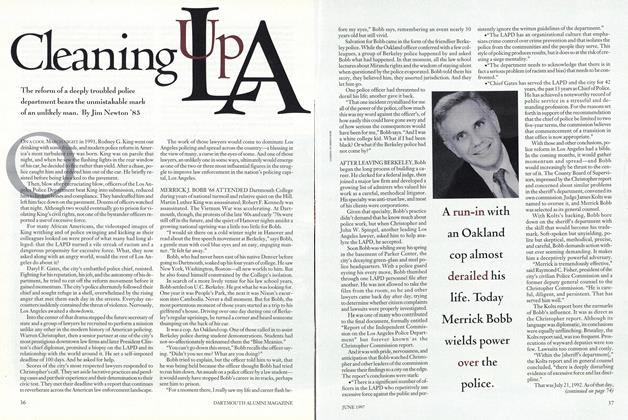

FeatureCleaning Up La

June 1997 By Jim Newton '85 -

Article

ArticleOf Appointments and Disappointments

June 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleA Cubicle of One's Own

June 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

June 1997 By Christopher K. Onken -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

June 1997 By Brooks Clark

Features

-

Cover Story

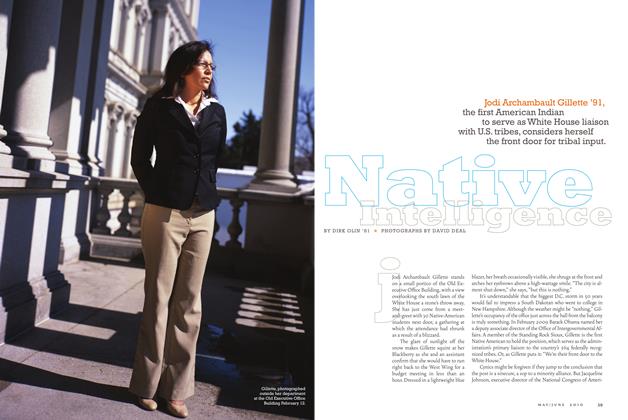

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureBraving the Alps

MARCH 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

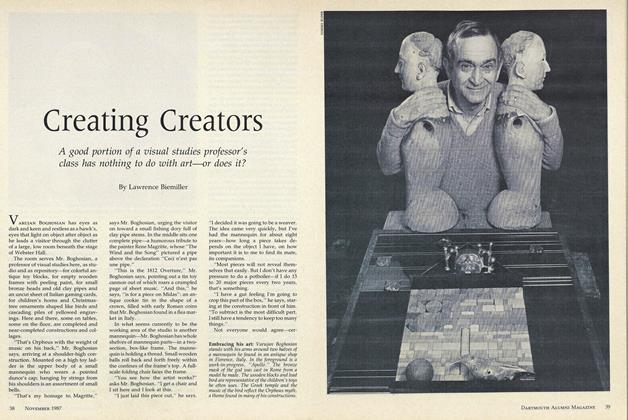

FeatureCreating Creators

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

FeatureArt Imitates Life

MAY | JUNE 2017 By LISA FURLONG -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R.