EVEN in a liberal arts college, it is a brutal assignment.

The Trustees have long known that Webster Hall with its flat floor, caverns under balconies, dead spots, and draughts is a lecture hall something less than perfect. A faculty lecturer dreads the place where if he moves a few feet from the microphone, his voice sounds absurdly falsetto and, when key words come up, becomes inaudible.

What Webster Hall itself lacks in vitality and resonance is made up by 750 freshmen. Many come from the best homes, and, singly, they have delightful manners. But Webster Mausoleum invites audible deviltry, stimulates vocal flippancy, foments noisy irreverence, and, eventually, induces slouchy sleepiness.

Nor is this all. The particular assignment for the new freshman course TheIndividual and the College is "The Aesthetic Life," a topic loaded with suspect terms. An inexpert lecturer just because he loves beauty has about as much chance to move gracefully and effectively before a Dartmouth freshman audience as an inexpert skier has when he points his skis straight down the Nose Dive on Mount Mansfield. An Assistant Professor of English, Dartmouth College, was given the assignment.

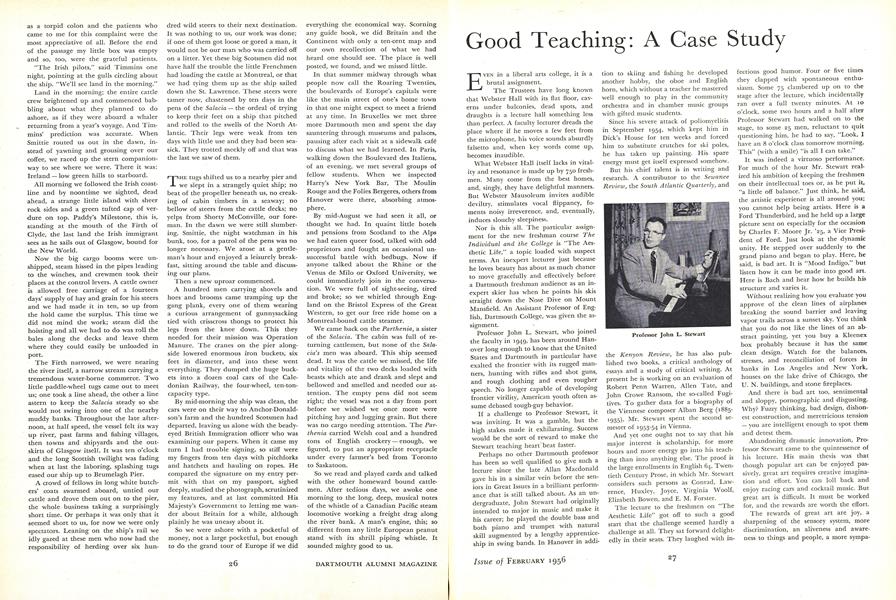

Professor John L. Stewart, who joined the faculty in 1949, has been around Hanover long enough to know that the United States and Dartmouth in particular have exalted the frontier with its rugged manners, hunting with rifles and shot guns, and rough clothing and even rougher speech. No longer capable of developing frontier virility, American youth often assume debased tough-guy behavior.

If a challenge to Professor Stewart, it was inviting. It was a gamble, but the high stakes made it exhilarating. Success would be the sort of reward to make the Stewart teaching heart beat faster.

Perhaps no other Dartmouth professor has been so well qualified to give such a lecture since the late Allan Macdonald gave his in a similar vein before the seniors in Great Issues in a brilliant performance that is still talked about. As an undergraduate, John Stewart had originally intended to major in music and make it his career; he played the double bass and both piano and trumpet with natural skill augmented by a lengthy apprenticeship in swing bands. In Hanover in addition to skiing and fishing he developed another hobby, the oboe and English horn, which without a teacher he mastered well enough to play in the community orchestra and in chamber music groups with gifted music students.

Since his severe attack of poliomyelitis in September 1954, which kept him in Dick's House for ten weeks and forced him to substitute crutches for ski poles, he has taken up painting. His spare energy must get itself expressed somehow.

But his chief talent is in writing and research. A contributor to the SewaneeReview, the South Atlantic Quarterly, and the Kenyon Review, he has also published two books, a critical anthology of essays and a study of critical writing. At present he is working on an evaluation of Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, and John Crowe Ransom, the so-called Fugitives. To gather data for a biography of the Viennese composer Alban Berg (1885-1935), Mr. Stewart spent the second semester of 1953-54 in Vienna.

And yet one ought not to say that his major interest is scholarship, for more hours and more energy go into his teaching than into anything else. The proof is the large enrollments in English 64, Twentieth Century Prose, in which Mr. Stewart considers such persons as Conrad, Lawrence, Huxley, Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bowen, and E. M. Forster.

The lecture to the freshmen on "The Aesthetic Life" got off to such a good start that the challenge seemed hardly a challenge at all. They sat forward delightedly in their seats. They laughed with infectious good humor. Four or five times they clapped with spontaneous enthusiasm. Some 75 clambered up on to the stage after the lecture, which incidentally ran over a full twenty minutes. At 10 o'clock, some two hours and a half after Professor Stewart had walked on to the stage, to some 25 men, reluctant to quit questioning him, he had to say, "Look, I have an 8 o'clock class tomorrow morning. This" (with a smile) "is all I can take."

It was indeed a virtuoso performance. For much of the hour Mr. Stewart realized his ambition of keeping the freshmen on their intellectual toes or, as he put it, "a little off balance." Just think, he said, the artistic experience is all around you; you cannot help being artists. Here is a Ford Thunderbird, and he held up a large picture sent on especially for the occasion by Charles F. Moore Jr. '25, a Vice President of Ford. Just look at the dynamic unity. He stepped over suddenly to the grand piano and began to play. Here, he said, is bad art. It is "Mood Indigo," but listen how it can be made into good art. Here is Bach and hear how he builds his structure and varies it.

Without realizing how you evaluate you approve of the clean lines of airplanes breaking the sound barrier and leaving vapor trails across a sunset sky. You think that you do not like the lines of an abstract painting, yet you buy a Kleenex box probably because it has the same clean design. Watch for the balances, stresses, and reconciliation of forces in banks in Los Angeles and New York, houses on the lake drive of Chicago, the U. N. buildings, and stone fireplaces.

And there is bad art too, sentimental and sloppy, pornographic and disgusting. Why? Fuzzy thinking, bad design, dishonest construction, and meretricious tension - you are intelligent enough to spot them and detest them.

Abandoning dramatic innovation, Professor Stewart came to the quintessence of his lecture. His main thesis was that though popular art can be enjoyed passively, great art requires creative imagination and effort. You can loll back and enjoy racing cars and cocktail music. But great art is difficult. It must be worked for, and the rewards are worth the effort.

The rewards of great art are joy, a sharpening of the sensory system, more discrimination, an aliveness and awareness to things and people, a more sympathetic and deeper appreciation of others and especially of one's own self.

But be warned. There are penalties attached to the appreciation of great art. Because of it, educated men experience self-doubt and discontent, the shock of ugliness, an awareness of human cruelty and injustice, and a passionate desire for self-improvement and social bettermefit.

And you must also realize, Professor Stewart said, that art is not a substitute for usefulness, religion, and philosophy. Art will bring you nonetheless excitement and a kind of creative happiness.

His lecture, he hoped, would be only a beginning of the aesthetic experience. To help the freshmen realize themselves, he passed out a mimeographed statement of five pages, single-spaced, in which he made suggestions about ways to explore the arts and to enjoy the pleasures coming with them. He had concrete suggestions and notes about particular novels, poems, essays, recorded and live music, the visual arts, the Orozco frescoes, art reproductions and prints, travel posters, modern houses in Hanover, industrial design, and advertising in the better magazines. He enumerated particular book stores, galleries, music houses, and periodicals where they could be easily obtained.

All in all, the challenge turned out to be not Professor Stewart's, but the freshmen's and few failed to meet it. They had considered a Ford Thunderbird from an aesthetic point of view and learned what it could and could not do for them. They had heard schmaltz played humorously and Bach expertly on a grand piano by an English professor. They had looked at abstract paintings, one by Professor Richard E. Wagner of the Art Department and one by Professor Stewart himself, though he was too modest to tell the students who did it. They had listened to a tough ballad by Robert Penn Warren far removed from the prissiness of roses-and-moonlight sentimentality of freshman stereotypes of poetry. They were surprised that an English teacher should consider Pogo good art. They weighed the evidence for and against "culture-vultures." The decorations in some college rooms and married men's dens seemed now somewhat corny. They viewed a distorted piece of sculpture without snorting contempt. They thought gravely about the tensions involved in an elongated El Greco painting of Jesus Christ.

In short, they took account of themselves in the United States and at Dartmouth, and of new frontiers, aesthetic frontiers, capable of giving them new horizons and a new growth.

It was a good evening.

Professor John L. Stewart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCATTLE BOAT

February 1956 By CHARLES F. HAYWOOD '25 -

Feature

FeatureAUTOMATION

February 1956 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

February 1956 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

February 1956 By THOMAS E. BYRNE, PAUL MERRIKEN

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksWINDOW IN THE SEA.

December 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE BULLS AND THE BEARS: HOW THE STOCK EXCHANGE WORKS.

DECEMBER 1967 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSELECTED WRITINGS OF OSCAR WILDE.

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureEleazar: The Man Behind the Myth

DECEMBER 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Books

BooksFEEL FREE.

DECEMBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE VISIONARY UNIVERSE PROPHECY.

June 1974 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

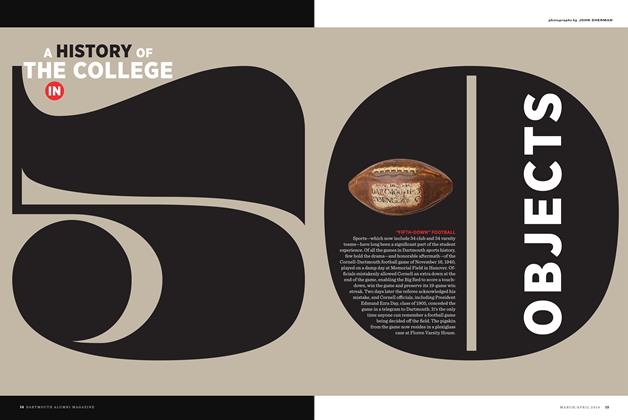

Cover Story

Cover Story"FIFTH-DOWN" FOOTBALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Matchmakers

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71 -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

DECEMBER 1965 By R.B. -

Feature

FeatureThe Past Is Prologue

JULY 1963 By T. DONALD CUNNINGHAM '13