By Marshall A. RobinsonHerbert C. Morton, and James D. Calderzoood. Washington: Brookings Institution,1956. 335 pp. $3.00.

As indicated by its contents and favorite reference work, this is predominantly an introduction to introductory economics as conceived by Paul Samuelson, who "Keynesian" approach is prescribed for' most American beginners. However, it is a bit less Keynesish, and it puts more stress on the"" "weigh the alternatives" technique recommended by President Calkins of the Brookings Institution. A sort of quick lunch for hurried laymen, it aims not at dietary balance but at providing energizers that will stimulate diners to seek the more body-building principles for themselves. Accepting its aim, it is attractive. Serious, well-written, and interesting, it helpfully suggests how one might reason about such problems as government revenue, government spending, government debt, and other cases of "political" economics.

The shortcomings of the book are such as it is logical to expect from its general kind. Scope: Of some six fundamental problems - level of employment, personal distribution of income, rationing of products (adjustment of demand to supply), regulation of relative outputs (adjustment of supply to demand), increase in per capita production, and an organization friendly to personal freedom - four are rather slighted in favor of the first and fifth. This follows almost automatically from neglecting the determination and equilibrium of specific prices. Method: Writing that is tailored to impatient readers entails fuzziness concerning basic concepts - averages and marginals, capital, profit, monopoly, etc. From this, apparently, comes some vague or questionable analysis. Just a few illustrations:

While telling readers not to think the whole is like its parts (and vice versa, presumably), the writers do not clearly adhere to their own advice. Thus, they occasionally refer to a whole economy's money and its "purchasing power" (power to purchase) as if the two terms were interchangeable, which

they are not. Again, to get an "accelerated" demand for one kind of capital good, they treat replacement demand, which really belongs to consumption, as if it were capital demand. As for the whole economy, there must be monetary inflation if the money demand for both capital and consumption goods is to increase; but in that case the inflation would seem to be the cause rather than the effect of "acceleration," if any. Once more, a part is likened to the whole by leaving the impression that a hike in the monopoly price of union labor "might" increase total demand as much as total cost. This is not so for any one firm or industry that uses mostly union labor. If it were, we should find

ourselves defending other monoply prices, too, on the astonishing ground that they maintain "purchasing power." Further, if laborers as a whole are to be subsidized, the subsidy should go chiefly to the poorer and more numerous unorganized workers, and it should not take the form of artificially high wage rates.

I hope it not unfair to believe this "a good book of a bad kind." A bad kind because short popularizations foster the harmful delusion that there is a royal road to economics.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reynold Scholars

June 1956 By PROF. JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureLEARN AMERICAN

June 1956 By EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16 -

Feature

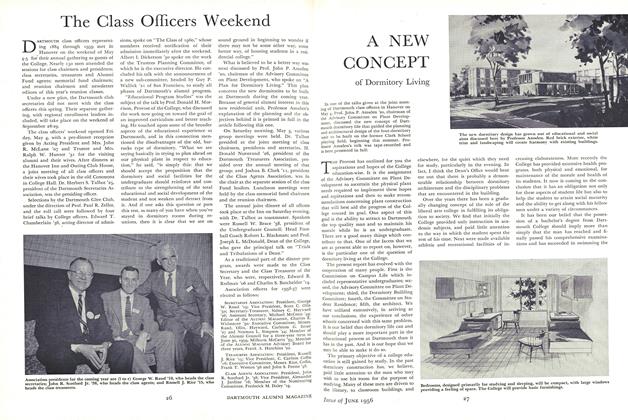

FeatureA NEW CONCEPT of Dormitory Living

June 1956 -

Feature

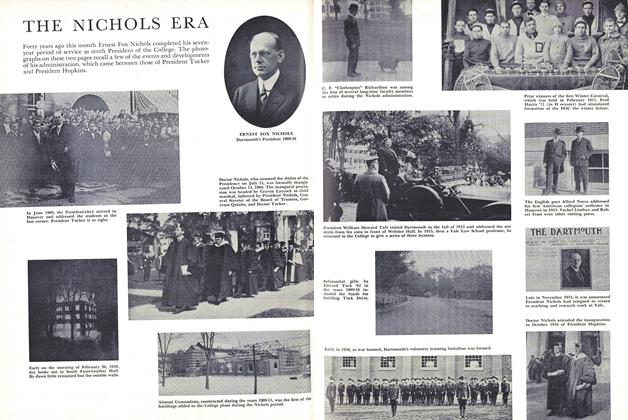

FeatureTHE NICHOLS ERA

June 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

BRUCE W. KNIGHT

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Books

BooksMOBILIZING CIVILIAN AMERICA

July 1940 By Bruce W. Knight -

Article

ArticleThe Coming "Boom and Bust"

October 1946 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT -

Article

ArticleOUR GREATEST ISSUE

December 1949 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT -

Books

BooksTHE RETURN OF ADAM SMITH

April 1950 By Bruce W. Knight

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

August 1924 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

December 1941 -

Books

BooksVARIETES MODERNES

July 1952 By Francois Denoeu -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY IN THE CONNECTICUT FRONTIER TOWN OF KENT.

October 1961 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksCITIZENSHIP AND CIVIC AFFAIRS,

May 1940 By Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksTHE IROQUOIS EAGLE DANCE AN OFFSHOOT OF THE CALUMET DANCE.

February 1954 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25