There are no musical "space cadets" in the

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

JAZZ glorifies individuality. Clarinetists develop tricky phrases; pianists grope for strange harmonies; talk is all of a "new sound." Legends of epic heroes such as Beiderbecke, who died pursuing some ineffable lost note, have made jazzmen glamorous. The student who can go "way out" on his saxophone is a campus personality, and in every entering class are quite a few men eager for glory at the cannon mouths of a brass section playing fortissimo.

The music of flute and harpsichord or of a string quartet is more subdued. Yet to some its players are heroic, too, in a wholly different way. For this music - chamber music - compels one to express himself with a closely disciplined unit. His imagination is precious, for without it chamber music would be flaccid and monotonous. Yet he must also have a control, flexibility, and awareness of the whole rarely found among the space cadets of jazz. His reward is music of remarkable richness and expressiveness achieved by joining many parts in a meaningful whole, but he earns it only by hard and often tedious labor. Understandably, not many men come to college hoping to join a string quartet.

Indeed, few colleges that do not award special degrees in instrumental music have student chamber ensembles. In the past, Dartmouth has had brilliant soloists but few such groups, and fewer still that have lasted more than a year. Since 1953, however, four members of the Class of 1957, none of them a music major, have maintained a string quartet capable of giving concerts in the Tower Room and before organizations in Hanover, Lebanon, and other nearby towns. Moreover, they have done it almost entirely on their own, for not until this year have they had professional coaching.

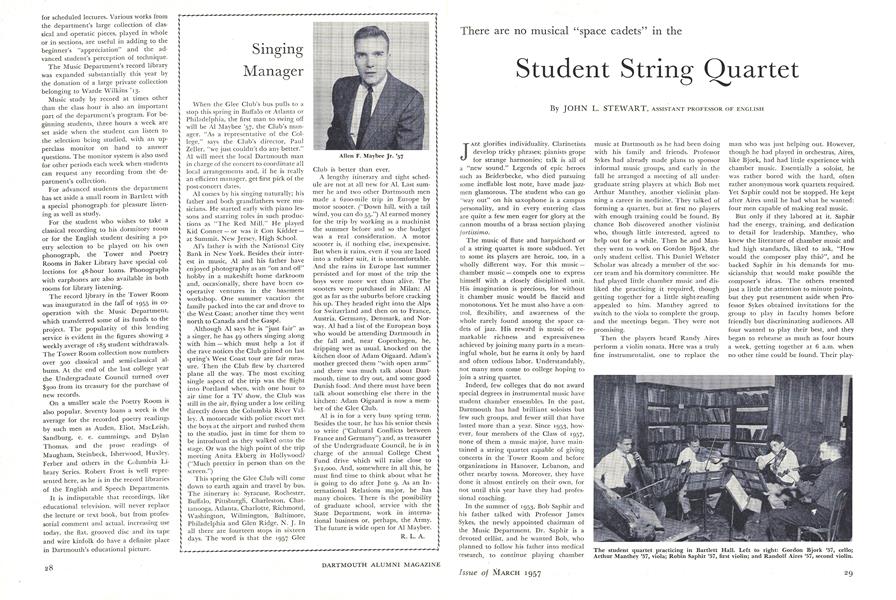

In the summer of 1953, Bob Saphir and his father talked with Professor James Sykes, the newly appointed chairman of the Music Department. Dr. Saphir is a devoted cellist, and he wanted Bob, who planned to follow his father into medical research, to continue playing chamber music at Dartmouth as he had been doing with his family and friends. Professor Sykes had already made plans to sponsor informal music groups, and early in the fall he arranged a meeting of all under graduate string players at which Bob met Arthur Manthey, another violinist planning a career in medicine. They talked of forming a quartet, but at first no players with enough training could be found. By chance Bob discovered another violinist who, though little interested, agreed to help out for a while. Then he and Manthey went to work on Gordon Bjork, the only student cellist. This Daniel Webster Scholar was already a member of the soccer team and his dormitory committee. He had played little chamber music and disliked the practicing it required, though getting together for a little sight-reading appealed to him. Manthey agreed to switch to the viola to complete the group, and the meetings began. They were not promising.

Then the players heard Randy Aires perform a violin sonata. Here was a truly fine instrumentalist, one to replace the man who was just helping out. However, though he had played in orchestras, Aires, like Bjork, had had little experience with chamber music. Essentially a soloist, he was rather bored with the hard, often rather anonymous work quartets required. Yet Saphir could not be stopped. He kept after Aires until he had what he wanted: four men capable of making real music.

But only if they labored at it. Saphir had the energy, training, and dedication to detail for leadership. Manthey, who knew the literature of chamber music and had high standards, liked to ask, "How would the composer play this?", and he backed Saphir in his demands for musicianship that would make possible the composer's ideas. The others resented just a little the attention to minute points, but they put resentment aside when Professor Sykes obtained invitations for the group to play in faculty homes before friendly but discriminating audiences. All four wanted to play their best, and they began to rehearse as much as four hours a week, getting together at 6 a.m. when no other time could be found. Their playing improved and their repertoire grew. When they returned for their sophomore year, they knew they would go on.

Still it was not easy. Strong-willed, they often clashed over how a piece should be played. They had 110 authority to guide them, and sometimes they disagreed so vigorously that a rehearsal would end with each refusing to speak to the others. But the whole meant far more than their parts, and they worked out compromises which balanced separate tastes against the need for coherence and unity. In the past year they have been helped by Mr. Gaston Elcus, a former member of the Boston String Quartet and for 26 years a first violinist with the Boston Symphony. His assistance has come at a good time, for Aires, now in his first year at Tuck School, has had to withdraw. He has been replaced by Adam Oigaard, an exchange student from Copenhagen, who brings to the music a European background similar to Mr. Elcus's own.

Their rewards? First has been that always startling delight that comes when four voices, threatening to break free, maintain a perilous equilibrium and come at last to rest in untroubled concordance. No amount of familiarity can diminish this pleasure. Then there have been new, hard-won insights into the music. Though its public repertoire is conservative ("We haven't really cracked 1850"), privately the quartet has explored Debussy, Ravel, and late Beethoven and gained new horizons of taste and understanding. Perhaps most important has been learning to work together on projects of great difficulty toward which each man has felt deep personal commitments. Few undertakings require more maturity, and in talking with these men one is impressed by their adult view of themselves and their experience.

They are not the only gainers. Officials at other Ivy League colleges have envied Dartmouth for having such a group, as well they might. For the quartet has done more than share its pleasure in music through its concerts. It has furnished the core for small chamber orchestras that accompany the Glee Club; it has performed music written by Benjamin Franklin for the New England Historical Society and for a class in early American literature; and it has been invaluable in building up good will for the College and in unobtrusively but profoundly modifying for the better some people's conception of the Dartmouth Man. Not all students know about the quartet, but those who do are not inclined to call it sissy stuff. One reason is that the players are not at all apologetic about it. Another is that one cannot easily dismiss something that Bjork, now a Senior Fellow in History and soon to be a Rhodes Scholar, takes so seriously. (He now thinks the group should practice more than it does.) It is hard to say just what effect the quartet has had upon the attitude of the students toward the fine arts, always regarded with a little suspicion at a men's college, but this effect may turn out to be its greatest contribution to Dartmouth.

When the Hopkins Center comes, Dartmouth will have the setting for creative work. Students will be able to watch it and perhaps catch some of the electric excitement that hovers about men making music or painting. The big question is the men themselves: will there be those with enough skill and dedication to

charge the atmosphere about themi Throughout their four years, the mem bers of the quartet have felt the need for companionship and friendly competition. Now, with June, their group will disband. Will there be another? Will there even be a time when chamber music players have to sign up for a place to rehearse because others need practice room too? Will a good violist have some of the prestige a hot trumpeter now enjoys? Those who know what these four men have done for themselves and their college hope the answers will all be "Yes."

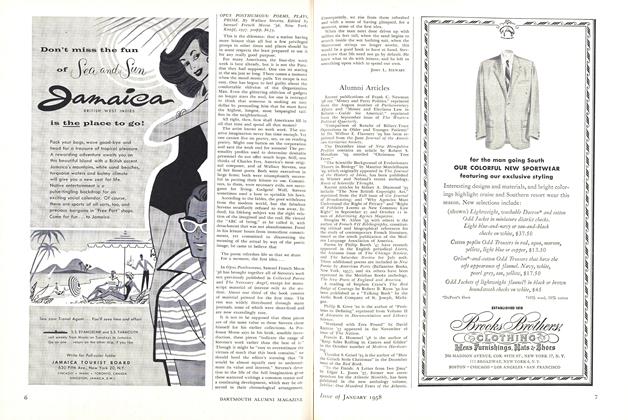

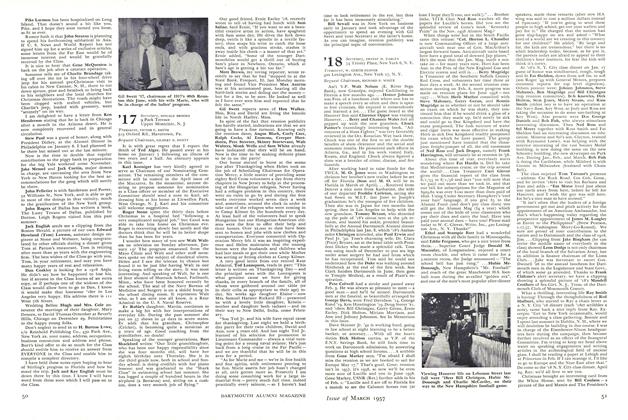

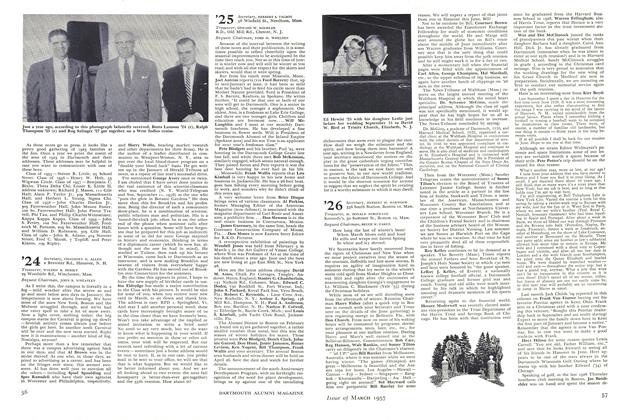

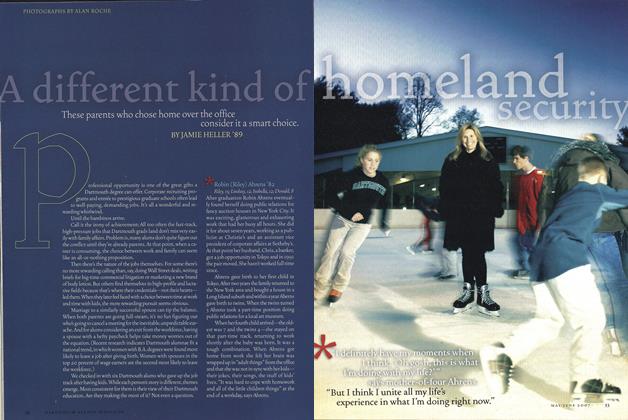

The student quartet practicing in Bartlett Hall. Left to right: Gordon Bjork '57, cello;Arthur Manthey '57, viola; Robin Saphir '57, first violin; and Randolf Aires '57, second violin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

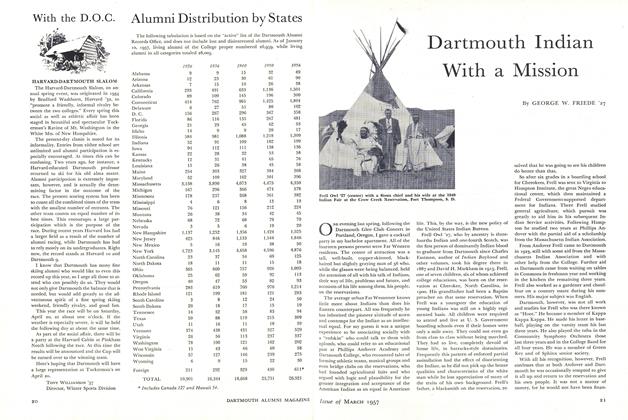

FeatureDartmouth Indian With a Mission

March 1957 By GEORGE W. FRIEDE '27 -

Feature

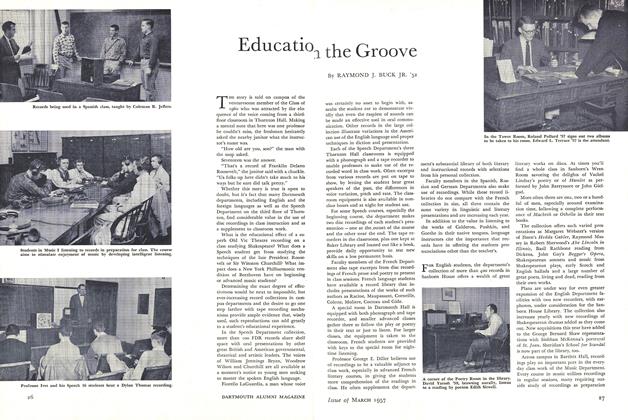

FeatureEducation the Groove

March 1957 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR. '52 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, BRUCE W. EAKEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1957 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES, TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

March 1957 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE

JOHN L. STEWART

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

OCTOBER 1965 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPIECE OF WOOD FROM MOLLY BLACKBURN HALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

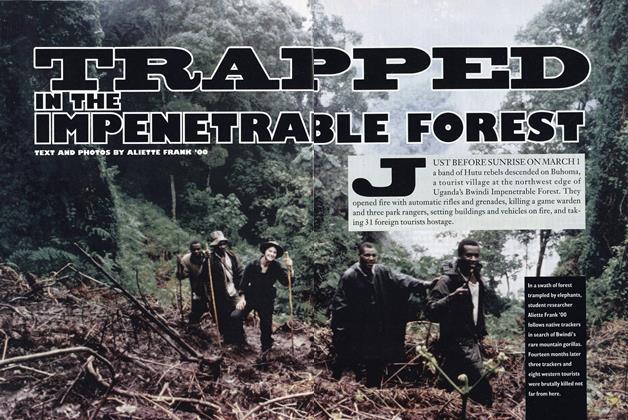

Cover StoryTrapped in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

MAY 1999 By ALIETTE FRANK '00 -

Feature

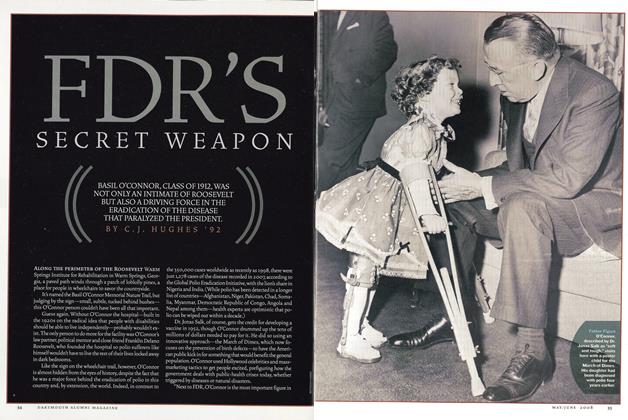

FeatureFDR’s Secret Weapon

May/June 2008 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureA Sluggo's Sister Chooses Dartmouth

MARCH 1997 By Gail Sullivan '82, T'87, and Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May/June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89