Panacea to some, bogey-person to others

DEPENDING on where you sit, it's glacier-like progress toward a worthy ideal, a minor nuisance, or nit-picking harrassment that distracts busy people from problems of real significance. Some see it as a breath of fresh air into the inbred insularity of the Dartmouth community, others as an instrument for the dilution of quality and the destruction of tradition within these ivied halls. Few are openly hostile, but hardly anyone is indifferent to the phenomenon called "Affirmative Action."

However you look at it, affirmative action is here, an unavoidable condition of doing business with the government. Uncle Sam wants to know not only how you plan to counteract any inequities that may have existed in the past, but how you are getting on with the job of insuring equal opportunity. In the third annual report to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, affirmative action officer Margaret Bonz finds Dartmouth making progress toward the goals enunciated in the 1974 plan. Is she satisfied? "In general, yes - with lots of buts."

Coming to the College two years ago from the University of Maryland, with an extensive background as a counseling psychologist and an educational ad- ministrator, Bonz is Dartmouth's first fulltime affirmative action officer. She succeeded Gregory Prince, assistant dean of the faculty, and Drama Professsor Errol Hill, who served part-time between 1972 and June 1975.

Dartmouth's plan, drafted originally, in 1972 and revised in 1974, received final approval from HEW late the following year. It was entered into voluntarily, without government pressure, Bonz points out, as a manifestation of a commitment dating back at least to the 1968 McLane Report on equal opportunity at Dartmouth. Viewed as a model, simple and straight-forward, it is only five to ten per cent of the actual bulk, for instance, of Harvard's or Yale's plan. If the College saw the handwriting on the wall, at least it saw it clearly and succinctly.

Confusion abounds about what affirmative action is and what it is not, what it requires and what it does not. President Kemeny has called it "one of the most controversial and misunderstood activities at universities today." Bonz says that what resistance she encounters comes from two sources: those few who automatically resist change of any sort; and, a far greater number, people who suffer from misconceptions about the principle, the practice, or both.

To use an analogy appropriate to hospitality, affirmative action is not merely opening the door heretofore effectively closed to certain groups; it is opening that door and issuing a loud, unequivocal call for them to enter and compete on an equal footing. Leaving the door slightly ajar and whispering the invitation whilst welcoming friends and neighbors in by the family entrance simply won't suffice. Affirmative action requires just what its title implies: positive steps to insure that positions on every level of employment - and graduate-school admissions - are available equally to all candidates, regardless of their race, sex, age, creed, or national origin; and that, once here, employees receive equal treatment in rank, pay, and opportunity for promotion and students have equal access to instruction, financial aid, and facilities. (Colleges like Dartmouth are specifically exempt from providing women, equal opportunity for undergraduate admission, that part of the law having been amended after intensive lobbying efforts by private colleges, with Dartmouth in the forefront, Bonz notes.) Colleges receiving federal funds, in the form of government-guaranteed student loans as well as grants, are under obligations to take affirmative action in a number of areas. Dartmouth, for instance, is required to recruit women and minorities for graduate-school and - with the exemption noted above - undergraduate admissions. It is obliged to broaden the pool of job applicants to include persons for all practical purposes excluded from consideration in the past by virtue of their race or sex. Once the applicant pool for a specific job has been conscientiously accumulated, there is no requirement that preference be given to. a woman or a minority candidate. To the contrary, hiring any but the most qualified candidate - be it minority or white, male or female - is, for the time-being at least, a violation of affirmative action. Only last month HEW Secretary Joseph Califano cast some doubt on this premise when he said, in a New York Times interview, that it was possible and necessary to endorse preferential hiring for jobs and admissions policies in higher education. In the wake of the furor caused by his advocacy of quotas, Califano conceded lamely that he was in error. What he really meant, he said, was equal opportunity for all.

IF today's Dartmouth provides a model plan for affirmative action, yesterday's serves equally well to, explain the raisond'etre. One need only glance back at the way it was and, until very recently has been, at the College to understand the rationale behind affirmative action. Of the 66 administrative officers here in the fall of 1950, for example, 58 were white males -48 of them alumni, and another seven either recruits from the faculty or officers teaching part-time. The eight female officers were tending to what must have been considered womanly duties; they included, in all, the President's secretary, the freshmen registrar, an assistant librarian. the alumni recorder, the managers of the Dartmouth Dining Association and the Outins Clubhouse, the assistant manager of the Inn. and the housemother/administrator at Dick's House. No women were listed as members of the faculty of either the undergraduate College or any of the associated schools. Hannah Croasdale, who had been at the College since 1935, achieved faculty status in the early '50s. She was at Dartmouth for 28 years before promotion to the tenured ranks, and she was made full professor of biology in 1968, only three years before retirement.

To compensate for the exclusivity of the past, Dartmouth's affirmative action plan states the equal opportunity philosophy, sets goals for future hiring of women and racial minorities, and specifies procedures which must be followed before job vacancies are filled. It spells out policies on such matters as nepotism, child care, and maternity leaves; calls for continuous monitoring; and establishes grievance procedures. It deals also with student affairs in the realm of admissions, financial aid, placement, counseling services, student activities, and housing.

The failure to distinguish between "goals" and "quotas" has been the source of greatest confusion about affirmative action, according to Bonz. Whereas quotas are declared to be in clear violation of civil-rights laws - except in rare court-ordered instances - goals are targets set in an attempt to approximate, within the limits of qualified women and minority-group members available, what the racial and sexual mix might have been had discrimination not existed in the past. For example, Dartmouth's goal of hiring 25 per cent women and ten per cent minority persons in faculty positions and 50 per cent women and ten per cent minority-group members in administrative positions within ten years takes into account the relative proportions of men and women of different races receiving Ph.D.s in academic disciplines or qualified to under-take administrative responsibilities. On the other hand, given the character of the local labor pool and the nature of jobs unlikely to attract applicants from beyond the area, the target for minority technical and clerical staff members and service employees is only two per cent, and the aim for the staff, where women already constitute the great majority, is to upgrade them to higher-level positions.

The current report indicates considerable progress, in overall numbers at east, although results vary widely among different segments of the College. Faculty and administrative personnel hired for this academic year, in numbers and percentages of new employees, include the following:

Women Minorities Arts and sciences, engineering 16 (46%) 6 (17%) Medical School 3 (21%) 0 (0%) Tuck School 1 (33%) 0 (0%) Administration 16 (41%) 3 (8%)

This year's new personnel brings the over-all totals to:

Women Minorities Arts and sciences, engineering 55 (17%) 25 (8%) Medical School 26 (21%) 5 (4%) Tuck School 1 (4%) 0 (0%) Administration 71 (26%) 17 (6%)

Comparable totals five years ago were:

Women Minorities Arts and sciences, engineering 12 (4%) 4 (1%) Medical School 20 (10%) 2 (1%) Tuck School 0 (0%) 0 (0%) Administration 37 (15%) 5 (2%)

Among academic departments, art, chemistry, and romance languages were cited for special effort; earth sciences, engineering sciences, geography, and religion for having no female or minority representation (religion has since hired a woman); English, classics, and psychology as having under-representation according to national availability data. Parts of the Medical School have been relatively unresponsive, Bonz says, particularly in regard to recruitment among blacks. "It's a different world up there, and they are preoccupied with problems many of them consider much more crucial." But she is not convinced the Medical School is looking hard enough or that some department chairmen are seriously committed.

Progress is similarly spotty among administrative departments. Of the 17 minority administrative officers within a corps of 276, 12 are clustered in student affairs. Among the areas lagging most in female and minority employment are general administration and development-alumni affairs. In the latter case, a continuing practice of hiring almost entirely alumni in responsible positions dictates a heavy preponderance of white males, at least for the time being. Many argue that the alumnus' familiarity with the College and its traditions is an invaluable asset in working with other alumni and that "old-boy" status should therefore be a legitimate criterion for employment. It is, however, one which has no standing under affirmative action requirements. "Dartmouth alumni are unquestionably a very able lot, but they have no corner on ability or the ability to do a good job at Dartmouth," Bonz suggests. "Conversely, people from outside can bring fresh attitudes and fresh approaches that might counteract the somewhat inbred nature of the Dartmouth establishment."

As a result of the institutional selfevaluation required under the law, College publications and the Athletic Council come in for special attention as needing "additional corrective action," the former in eliminating use of sex-linked pronouns, the latter in several areas: publicity, facilities for women coaches and women students; equal physical-education responsibilities for men and women coaches; support staff for women's athletics; additional full-time women coaches and better salaries for part-time; inconsistent funding for men's and women's programs; enrollment activities, training table, and equipment; and salary inequities. Athletic Director Seaver Peters '54 and a DCAC affirmative action sub-committee have drawn up goals and timetables for full compliance by the July 1978 deadline. "There has been enormous improvement in the DCAC," Bonz comments, "but the change in attitude is not across the board!"

Peters counters by citing the special problems peculiar to a sports program. The hiring procedures, which he concedes are helpful in forcing careful examination of a large pool of candidates, thereby preventing costly mistakes, can also cause agonizing delays in filling coaching positions. "When the head basketball coach resigns on April 1, as Marcus Jackson did [in 1975], and you have to spend two months looking at candidates, you've lost a whole recruiting year." He claims too that the law is not applied nationally, that places like UCLA and Notre Dame somehow are able to fill coaching positions within days. He sees some of the targets for his department, even though they were approved by the DCAC, as unrealistic and the goals becoming quotas - or "gotas," as he calls them. The plan aims at four or five minority coaches, a formidable goal in Peter's view, considering the difficulty of attracting blacks to a rural, mostly white community. He wonders about equal pay for women coaches "who don't have to spend half their lives recruiting," but he's all for better facilities for women athletes - and men, to boot. He feels "the burden of the federal government," exemplified at the moment by the paperwork involved in proper consideration of some 900 applications prompted by the required advertising of a vacancy in sports information. President Kemeny too, in his five-year report, has commented that "the greatest burden imposed by affirmative action is the vast amount of red tape."

Ahead count of women and minorities alone is not necessarily a reliable measure of a department's commitment, in Bonz's opinion. She's convinced, for instance, that the Tuck School, which has until this year had a 100 per cent white male faculty, has made a genuine effort against a real availability problem and that Thayer often beats the bushes in vain because of a dearth of women and minority males qualified in engineering. She is abundantly aware, on the other hand, that availability is frequently used as an excuse for half-hearted recruiting, in compliance with the letter of the law but without a serious attempt to seek out women and minorities to broaden the applicant pool. Sometimes the pro forma search is deliberate: with the candidate the employer wants already identified, he or she merely goes through the motions; occasionally, it is self-dejuding: the employer really thinks all avenues have been explored, even though the casting of nets has been perfunctory.

Tucker Foundation Dean Warner Traynham '57, to the contrary, believes the numbers tell the tale. "You can gauge commitment by counting how many women and minority men have been hired. Where there is commitment, something is going to happen; where they have tried, they have succeeded. It may not be kind, but it's true."

A high turnover, particularly among blacks who have come to Dartmouth in recent years, is a subject of concern. Despite a hiring rate that has climbed as high as 20 per cent of new personnel, the report notes that "the total number of minority officers has remained almost constant for the past five years." Since the appointments are at lower levels of faculty and administrative staffs, when the people are just starting their careers and are thus upwardly mobile, many tend to spend a short time at Dartmouth and go on to better jobs elsewhere. Bonz suspects that the trend is no greater among minority officers, that their small numbers just make their departures more visible. But lack of opportunity for advancement, the high demand Generated by affirmative action plans at other institutions, and Dartmouth's relatively uncompetitive pay in the lower ranks unquestionably contribute to the high attrition rate. It is probably a fair surmise that women are more likely to be "captive," with their husbands settled in the area, whereas men, white as well as minority! are more easily lured away by higher salaries and more responsible positions.

The major point of concern with Traynham and Bonz and many others in the College community remains the scar-city of either women or minorities in high-level jobs, a specific goal of Dartmouth's affirmative action plan toward which little or no progress has been made. The current report notes that no women are department or program heads; that following Vice President Ruth Adams' retirement in June no woman or minority will hold an academic deanship or vice-presidency; that, of a tenured faculty of 171, only six are women and just two are black men (two more blacks have been granted tenure this spring); that there are no women Trustees. Only two of the 17 minority administrators and seven of their 71 women colleagues hold grades higher than five on a scale of eight. With Adams retired and her job phased out, no woman or black will sit on the highest policy-making boards or committees: the Planning Board, which decides on all buildings and facilities, or the Committee on Administration, which passes on all jobs. Representation is minimal on other powerful committees.

Their concern is the greater in that, with the recent promotions from within the College of Addison Winship '42 and Paul Paganucci '53 to vice presidencies and of Ralph Manuel '58 to the beefed-up deanship of the College, the situation is effectively locked in. Barring unforeseen resignations, there will be no top-level openings for some time to come.

Traynham, whose dismay at what he termed "circumvention of affirmative action" in Manuel's promotion was reported here last month, calls the tight hold of white males, predominantly alumni, on the decision-making structure of the College "the cosiness of power." "It's not that they're bad people," he says, "but that they're all the same. They tend to have the same backgrounds; they work on the same assumptions." He sees the custom of filling top-level vacancies from inside the institution. though in compliance with the letter of affirmative action, as violating the spirit by perpetuating white male control. It is not enough to fill from within," he contends. "Affirmative action requires lateral movement of blacks and women. There are simply not enough in the lower-echelon pool for equal access to top positions."

Hanover and Dartmouth together, Traynham says, constitute "a self-selected community. How well it is run is testimony to the graciousness and benevolence of the institution. There is much that is valuable here, but the College is out of step. It needs reality-testing. Dartmouth ought to be given credit. It has done something - and it hasn't been easy - but it could do better if it really had the mind for it." He attributes the slow progress toward affirmative-action goals to "lack of imagination and the absence of pressure. For a few years now, there has been a tranquil response to everything that happens here. People need pushing."

When it comes to hiring minorities and women for high-level positions, Traynham works from an "if-we-can-put-a-man-on-the-moon-we-can-attract-a-black-to-Dartmouth" stance. "Things get done when people say 'By God, we're going to do it!" That's the way to make social change." He finds it interesting on search committees to watch "very capable people suddenly become woefully ignorant and thoroughly incompetent about how to seek out qualified women or minority applicants. Then they fall back on 'we need an insider.'" It has come to the point that he has decided not to serve on any more search committees. "Until the searches become more exhaustive, my black face won't be at the table to legitimize the actions." Bonz agrees that in some of the top-level searches there has been something less than "real intent to give women and minorities a fair opportunity."

If the affirmative action procedures are not followed to the letter, Bonz has the authority to block an appointment, a measure she has used on rare occasions. But commitment to the principle, defying measurement, cannot be dealt with directly. Where she is skeptical as to whether a genuine effort has been made, through lack of either will or way, she can do little but accept the fait accompli. If she observes patterns emerging within a department or administrative area, she calls it to the attention of President Kemeny, to whom she reports directly. She does not make the decisions on whom to hire; the choice of the best qualified candidate remains within the jurisdiction of the department.

As Bonz carries out her charge of seeing that Dartmouth lives up to the commitment of its affirmative action plan, she runs into fine cooperation from some sources - particularly academic departments - and very little outright hostility from any, and then only to the principle, not to herself as a person. She sees herself not as an adversary, but in a helping capacity working with departments to keep the College square with the law. "Most people will go along," she says, "because they understand that the institution is in jeopardy otherwise. Their attitudes may remain unchanged, but they will take action." Where hostility does exist, it is rarely revealed outright. "They've been so cooperative, so interested - all those good things - talking to me, and then the comments made elsewhere filter back later."

Most of the 50 grievances noted in this year's annual report were settled by consulfation, with only 11 requiring formal investigation and one coming to a committee hearing and recommendation to the President for his final disposition. Two were complaints of reverse discrimination, both resulting from denial of tenure. "The national hue and cry over reverse discrimination" Bonz believes to be out of proportion to the problem. In general she attributes it to "the inability of white males to accept the fact that women and minorities can compete on an equal basis or to concede that they really can be better." To the contrary, she is apprehensive lest, "in our anxiety to avoid the charge of reverse discrimination, we perpetuate a 'super-woman, super-black' mentality. When a white male is promoted, we don't have to spend all the time in justification that we do in the case of a woman or a black. Because of the national hue and cry, we may find ourselves bending over backwards to be so sure we aren't discriminating against a white man." As a result, where women or blacks once had to be ten times as good as white men to get similar jobs, Bonz thinks that now they only have to be nine times as good.

You've come a long way, baby - maybe.

"The greatest burden imposed by affirmative action is the vast amount of red tape."

"It's not that they're bad people but that they're allthe same ... they work on the same assumptions."

This is the second in a series of articlesbearing on the condition of women atDartmouth. The first, a survey by KelleyFead '78 of attitudes held by recent alumnae, appeared in the November issue. Nextmonth: a report on the women faculty atthe College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTopeka Takes On the Hun

April 1977 By NICK SANDOE '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

April 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., LOUIS N. PERRY

MARY ROSS

-

Article

ArticleYankee Editor

MARCH 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

APRIL 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1960 -

Feature

FeatureDrama Critic

MARCH 1968 -

Feature

FeaturePLATT

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

FeatureThe Green Curve of the Future

JANUARY 1969 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

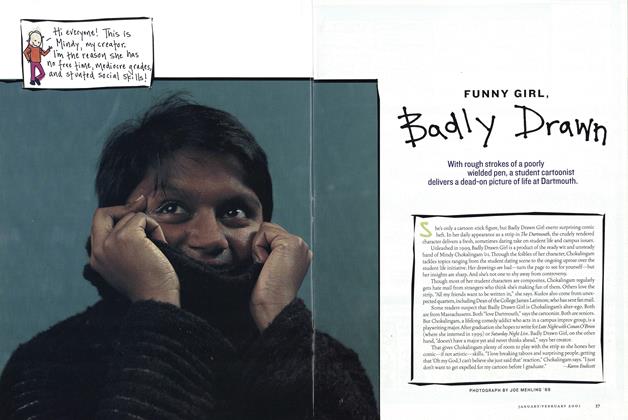

FeatureFunny Girl, Badly Drawn

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott