The Return to the Sources Jesus went away again beyond Jordaninto the place where John at first baptized;and there he abode. And many resorted unto him, and said, all things thatJohn spake of this man were true. (John 10:40-41).

DEAN OF HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL

How natural it was for Jesus to take such a step as this - to return, in the midst of his many difficulties, to the place where he had first found strength!

As a young man he had come to the place on the Jordan where the picturesque but mighty John the Baptist, clothed in animal skins and living in the desert, was baptizing people who wanted to dedicate themselves to God. He had offered himself for baptism - and in the very moment of the act he seems to have acquired the mystical knowledge that God had sent him into the world to accomplish a great purpose. It is recorded that he went from that place "full of the Holy Spirit."

From that time on he had begun to preach to the people. At first they hung on his words and success attended him. It was not long, however, before the authorities of the land felt him to be a divisive force and set about putting him out of the way. Though many believed in his mission, there were others, whom he met in almost every village and town, who heaped difficulty on his path before him. It was all presently to have its tragic climax in the crucifixion itself.

Now, in the midst of evils and in the midst of the apprehension of worse evils to come, Jesus returned to the place where he had first received his mission, and though we do not know what happened there we know that he came out of that place with strength sufficient to face any circumstance which life would throw against him. And there were at least some who were then aware of his inner power: "And many resorted unto Him, and said, all things that John spake of this man were true."

It is a reconditioning experience for any of us to go back to the place where a new access of life came to him. Some of you may remember the spot whence you first saw the sea or the mountains: "Then felt I like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into his ken. Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes he gazed at the Pacific and all his men stared at each other with a wild surmise, silent upon a peak in Darien." To look later at the planet which you saw first of men or to stand in after years on that peak in Darien is to live again through the bright, original moment of awe and discovery. I know a man who returns every summer to the White Mountains through the Franconia Notch, though it is long way round for him, simply in order that he may hear again the words that the mountains spoke to him when they were first seen at this very point in his youth.

So you will come back to your reunions in after years. Now reunions, when one examines them with the cold eye of the philosopher, do not add to your income; and they probably do not enhance your health (unless you have learned to live, like a fish, without closing your eyes). Reunions do not add greatly to those values which practical Americans are said to live for, and yet you will return to this campus again and again because you know that the entire environment will conspire to kindle in you once more the glow of youth and youth's experiences. In Locksley Hall Tennyson records a hope shining through a failure; and sixty years after, the same scenes awaken in him a similar sentiment: to look externally at the place with its "sandy tracts" was to bring back an internal experience of victory - not unclouded, but none the less victory. Many a couple who have been man and wife for many years find a kind of youth again when they go back to the place where they first declared their love to each other. So the memory of college life is a mosaic of details of fresh discoveries of oneself and one's fellows, all and any of which may be renewed and re-lived by repairing to the old haunts. This is good. The place itself, revisited, seems to furnish strength.

BUT if college is only a place of reminder, able to feed its strength back to us only as we return to its elms, how does it differ from any spot where we may have entered into the tingling new dimensions of maturity? It is actually much more than a spot: it is almamater sapientia exuberans - a dear foster mother rich in wisdom. If she has not waked us up intellectually she has not performed her maternal function. This is indeed the very marrow of her purpose. After a college course every man or woman should be able to say with Rupert Brooks:

Now God be thanked who hath matched us with his hour And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping.

In the area of the mind, the college is God's mediator. It opens to us a book of life to which we can ever after return. Barrett Wendell, the teacher of English at Harvard who ruled like an emperor in the domain of literature, was first made aware of the incandescent fire that lies in pure poetry by the reading of Dante; and it is evident from his writings that for a re-illumination of his mind, he might at any time return to the Divine Comedy. This is the task of a college, to open one to sources to which at any time he may return and be refreshed.

The extent of such aid which a college can give one is the extent of the known universe. To give a man knowledge of how to go back to sources is to give him a key to life. Years ago I carried an invitation to a European scholar to come to live in the United States. "But I cannot leave my sources," he rightly responded. Today, with the development of the great American libraries, he would not have had to give such an answer, but in that yesterday he would have cut himself off from the springs of life in his own field. One of the reasons, it is said, why the Japanese people before the war seemed to be inferior to some of their neighbors in their speaking of the English language was because of their very self-reliance. They wanted to teach English - as they had learned to teach almost everything else - themselves. So they failed to return to teachers who spoke it as their mother tongue. When the English you use has been learned from a teacher who learned it from a teacher who learned it from a teacher, with no contact on the part of any with others who spoke it well, your compositions are likely to qualify as illustrations of the strange ways of the mysterious East. A whole section of the very early history of New England has recently had to be rewritten because the historians for a century or more had depended upon previous historians who had gone astray. Those of today have corrected themselves by going back to the original sources.

A college is one of the most marvelous instruments developed by the human race, for it is the point at which the rich wisdoms of the past are brought together and made available. This is what makes it an institution of learning. Here you can hobnob with Aristotle, St. Paul, and Da Vinci. Heaven has often been defined as a spot where one could converse with the mighty men of yesterday and in this respect the college has a celestial quality. If ever any of you lived with primitive tribes you must have stopped to ask yourself what the difference is between their society and that of the modern West. Doubtless there are many differences, but one is crystal clear: though the average boy of the tribe may seem as bright about the things of nature as any average boy you know, the tribe's universe of discourse - about weather, food, drink, shelter, loyalties, and the rest - is infinitesimal compared to that which is available to the western mind. And the college or university is the most conspicuous single medium developed by modernity for the assembling, preserving, and dispensing of the world's knowledge.

Now at your twenty-fifth college reunion, though it will be evident that the place has renewed the spirits of all, it may become equally apparent that some of your classmates have not really had any conversations with Aristotle or anybody like him since they graduated. When they graduated, they closed their books and have not opened them again. The diploma has been a passport to mediocrity. Life in their bodies has deceived them into thinking they had a continuing life in their minds. They have left the intellectual sources which are basic to our western civilization and have taken in their place the catch-as-catch-can standards of the coffee hour. They are not bad people, but only not significant, having no real meaning for themselves or their times. Quantitatively they bulk large: qualitatively I am afraid that the Bible would describe them as the chaff, which the wind driveth away. You have to ask yourself whether it was worth while for them to go to college at all.

What an experience of richness it is, in the midst of such a company, to run across a man who has plainly kept close to his sources! He is a business man, who is more than a good organizer: he knows the history of his trade. He is a lawyer who knows more than the little precedents of the cases he has recently looked up: he knows something of the philosophy of the law and has considered how jurisprudence flowers from the basic morality of human society. He is a doctor who, like Sir Thomas Browne, has done some thinking about the life and death with which he constantly deals. "I thanke God," said the author of Religio Medici, "I have not those strait ligaments, or narrow obligations unto the world, as to dote on life, or be convulst and tremble at the name of death: I find not anything therein able to daunt the courage of a man, much lesse a well resolved Christian." A cultivated man is the one who knows not only his trade, but the broad humanities from which it draws. It is perhaps for this reason that many medical schools have ceased to ask for the narrower pre-medical courses which were in vogue at one time.

WHEN Jesus went back to the place where he was baptized, he also went back to a rite which was a gateway into his whole Hebrew heritage.

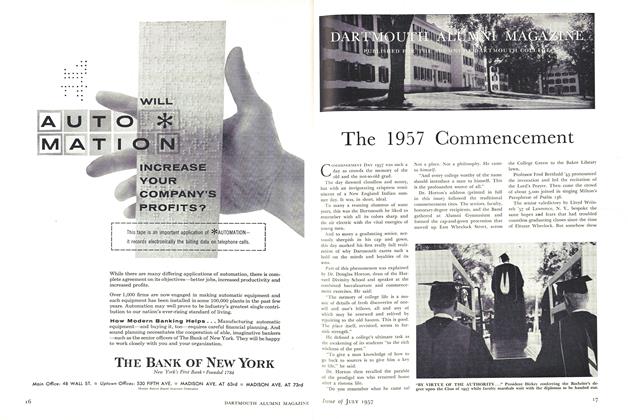

But I do not believe that it was either the place or the inheritance of ideas to which Jesus returned that gave him the renewed vitality at which our text hints, though each has its place as a medicine. A college can give one a place to return to: it can do more — it can make him heir of the past ages to enrich him in his professional life. But what one craves, besides these, is a deep moral preparation for life. Where can I go to be prepared for anything the future may have in store for me as the return to the Jordan prepared Christ for crucifixion? I think the answer is given in the parable of the prodigal son: do you recall that the turning point in the life of the young man, after he had gone into a far country and devoured his substance in riotous living, was that in which he arrived at something. Do you remember what he came to? Not a place. Not a philosophy. He came to himself. And every college worthy of the name should introduce a man to himself. This is the profoundest source of all.

The greatest sages of all the ages keep telling us with Socrates to go back to this source: "Know thyself." You have it on the Greek side: "There are many wonderful things in life, but none so wonderful as the soul," and on the Hebrew side: "What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?" One needs something more than happy and enlivening memories, something more than repositories of learning to which he may repair. By these means one does not necessarily achieve nobility of character. Polonius' advice to his son was not to be true to his memories, nor to his ideas: "To thine own self be true, and it will follow as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man."

This implies getting back to one's real self. And what is that? Are you, as the Marxists seem to say, a physical organism caught in a nexus of cause and effect from which nothing can deliver you? If that is really the ultimate description of yourself, why have the thinkers made such a to-do about so essentially meaningless a matter? And why and whence comes your own strange suspicion that you are really something more? Recall for a moment the most famous cartoon of the First World War. The Kaiser, whose armies have overrun Belgium, in spite of a treaty guaranteeing against this, is shown pointing out the ruins of the country to the king of the Belgians, who has resisted in the name of decency and human freedom, "So, you see, you've lost everything," says the emperor. "Everything but my soul," says the king. There is something deeply right about the reply, as the millions who responded to the cartoon throughout the free world attested. But if the soul is simply a physical factor, the reply is obviously silly.

But now suppose that your self is something you cannot describe at all because it can never be quite objectified but that it has the faculty (which it seems quite clearly to have) of being the point at which you become creative, at which you draw something from the unseen world into the seen, at which you carry out the will of an invisible God in a concrete world, at which you respond existentially to standards which are not of this world? If that is your real self and you stay close to it, you can actually achieve the power to decide not to remain quietly behind in Nazareth, where the food is good and the work plentiful, and some girl might even consent to love you, but to show the world something of the love of God, through the desperate expedient of being crucified. This kind of courage is given to those who discover that this kind of self is the one they really are, and return to it.

Suppose your self has the ability to see things not only as they appear but with a sense sublime of something far more deeply interfused? Suppose it has the quality of seeing a flower and seeing in it the handiwork of God? "Consider the lilies of the field. Even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Wherefore, if God so clothed the grass of the field, which today is, and tomorrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith?" Paul Tillich the theologian will not allow anyone in his class to say "only a symbol" - for symbols are what we live by. How did the thought of God ever enter the mind of the human race? He has never been seen, never been heard, never once to any man or woman appeared in the world of sensory perception and yet many have known that the thought of him is the greatest that the human mind can entertain. This is because we are able to see life sub specieeternitatis, to look beyond the symbol to the invisible reality, to see life sacramentally, undergirded with meaning.

There is never a situation which is not more than it appears to be. St. Augustine stood once with his mother by a window, "the invisible world wrapping them around," as he said. The invisible world wraps us around all the time. There are overtones of heavenly meaning in every choice of our life, and the true self is that which is aware that these overtones exist and seeks after them. To go back to that soul is to go back to a source of unfailing strength.

So Jesus returned "into the place where John at first baptized." There he came to his true self. That was the beginning of his power.

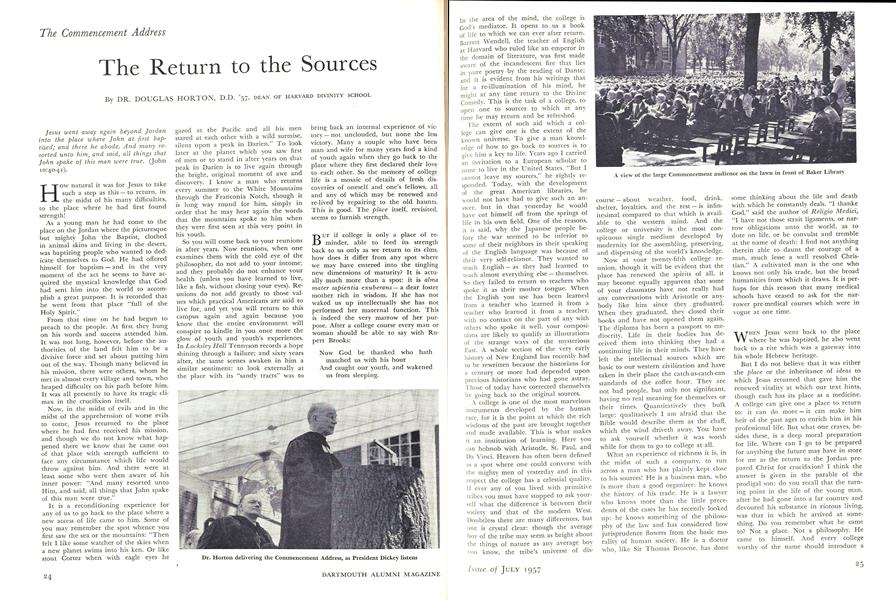

Dr. Horton delivering the Commencement Address, as President Dickey listens

A view of the large Commencement audience on the lawn in front of Baker Library

Thomas E. O'Connell '50, who has resigned as executive assistant to the President to take a post with the New York State Budget Division, poses with President Dickey just before the start of the academic procession.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHopkins Center and Dartmouth Hall

July 1957 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1957 By JAMES M. O'NEILL '07 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1957 By LLOYD L. WEINREB '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1957 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54

Features

-

Feature

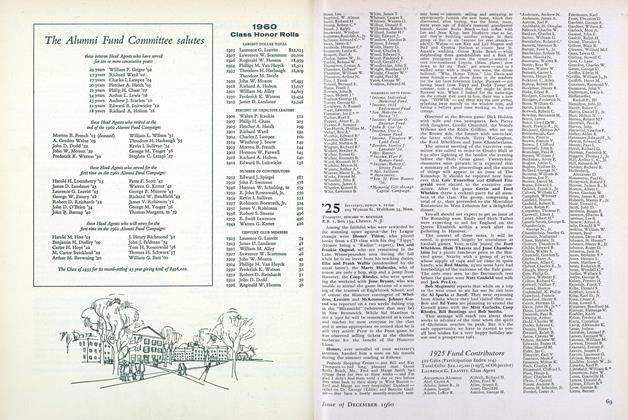

Feature1960 Class Honor Rolls

December 1960 -

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Cover Story

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Feature

FeatureIs Vietnam Still Claiming Some of Us?

December 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

Feature"Turn Our Penitence Into Dedication"

NOVEMBER 1963 By Reverend Richard P. Unsworth.