PROFESSOR OF GREEK AND LATIN

FROM the point of view of a Dartmouth teacher whose work will be affected by the Hopkins Center, I write this brief account of (a) what I now try to do as a teacher, (b) what effects the Center seems likely to have on what I now do, and (c) what new things the Center will enable me to do - things that I cannot do now and should be doing.

(a). The first two courses in our historical sequence are Origins of the ClassicalTradition and The Classical Traditionand Rome. In these I try to introduce our men to the architecture, sculpture, painting and other visual arts of such ancient peoples as the Sumerians, Persians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Hittites, Cretans, Greeks, and Romans. In selecting material from this range, so tremendous geographically and historically, I exclude specimens with limited life and meaning for us here and now and confine discussion to works of ancient art which have dominated the taste of some or all later epochs in western civilization including most particularly our own. This is also the policy in our other historical courses with the result that we all use as illustrative material works from all periods of art. The practical problem in this plan is obvious: we find that our collections of such illustrative materials as original works, models, casts, films, slides, prints, etc., are often needed by several of us at the same time. Our present space for illustrative displays is limited to our classrooms, all of them used by other courses as well as our own. If the members of this department were not the courteous company of gentlemen which we are, we should present the disconcerting spectacle of placid scholars forced to pilfer materials from the classrooms of others and eventually inflicting nasty flesh wounds on each other.

(b). So, one effect of the Center will be, we hope, to permit use of the present galleries for departmental displays of teaching materials, arranged in a series designed to meet the rightful needs of our students and to restore some degree of equanimity in the minds of us teachers. This is such an obvious pedagogical necessity that I will not labor the point. Use of the present galleries for this purpose, also, will make an incalculable difference in the time and physical effort demanded by preparation for lecture-discussions. As you know, the proper teaching of art requires that the student be exposed to illustrative materials, not merely as a supplement to reading a textbook but as the very stuff of which instruction consists. Such materials are difficult to assemble, bulky to transport, and infuriating to display effectively. When the necessity of doing all this in a classroom is added, plus the flurry of getting it done after one class ends and before the next begins, then just tearing it all apart again because of a third class coming up, one wonders why he teaches art anyway when he might teach English out of a textbook which he carries under his arm.

(c). Down home in Maine we often say, in our crude way, that fish-balls are the best part of the fish. Now, the best part of the fish under discussion is that we shan't teach art at all as we now do. We have all always believed that aesthetic experience arises either from creation or contemplation of art and that self-respecting teachers of art should encourage both approaches. The department presents courses to sub- stantiate this thesis and this cross-fertilization of the urge to understand art and the itch to participate in it is the most rewarding aspect of our work, in my judg- ment, both to students and to teachers. At present, however, the practice of art and its study are separated by our physical limitations, and this should not be and will not continue in the Center. There the synthesis of seeing, feeling, and understanding objects of art with the related experience of creating them will be possible. The instruction can move, as it should, from illustrative display to studio and shop without break and loss of continuity. It seems to me that this well-at-tested trend in the teaching of art, now becoming nationally recognized, may lead to important changes in educational philosophy during the next decade or two. The traditional concept of the liberal arts has not been based upon doing as a component of the process of learning. If the logic of events to come, however, should require that the basis of the A.B. degree be widened to include more doing and less reading, instruction in art would not, in my opinion, be hurt by this shift of emphasis. It seems likely that such a shift in art is inevitable anyway and almost as likely that the trend in art may spread to other disciplines. If this is true, Dartmouth may be, with its Center, in a strategic position to pioneer in such changes as circumstances demand.

As natural with a teacher, I have discussed first the contributions which the Center will make to teaching. I admit, however, that not all students at Dartmouth study art and that many a boy gets his aesthetic training informally. To me this is the most significant potential of the Center, for I believe that the unquestionable increase in consciousness of art among Americans of all kinds makes a gallery-studio imperative if Dartmouth is to fit men for intelligent participation in modern life. This impressive widening of interest in art, although not so commonly talked about as popular interest in good music, seems to me one of the really seminal aspects of this generation's viewpoint. I think this interest in art and music is probably the biggest difference between my classmates and my students.

Professor John B. Stearns '16

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

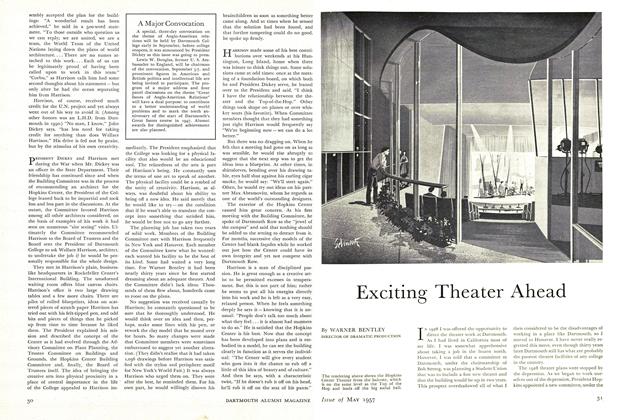

FeatureExciting Theater Ahead

May 1957 By WARNER BENTLEY -

Feature

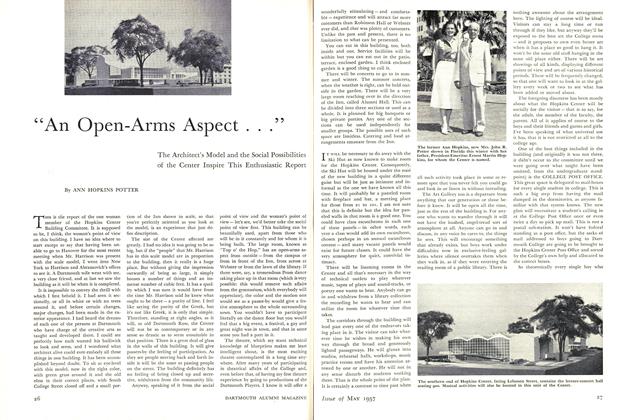

Feature"An Open-Arms Aspect ..."

May 1957 By ANN HOPKINS POTTER -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Who Designed the Center

May 1957 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureDramatics

May 1957 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

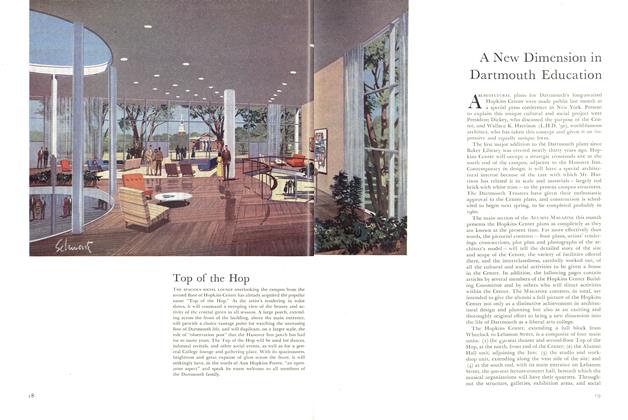

FeatureA New Dimension in Dartmouth Education

May 1957 -

Feature

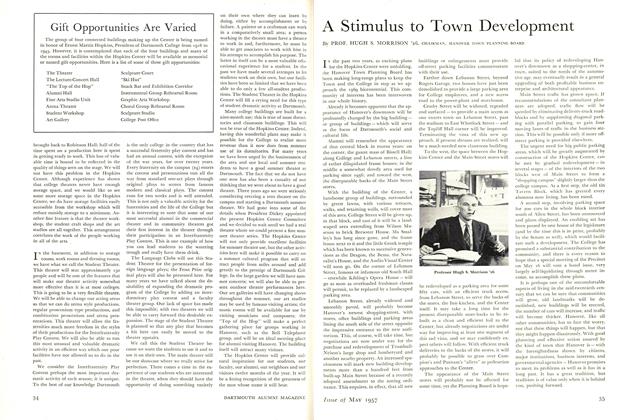

FeatureA Stimulus to Town Development

May 1957 By PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26,

JOHN B. STEARNS '16

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleGEORGE DANA LORD

August 1945 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

March 1952 By John B. Stearns '16 -

Books

BooksOUR FLIGHT TO ADVENTURE.

January 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE POETRY OF GREEK TRAGEDY.

July 1958 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE THREAD OF ARIADNE: THE LABRYINTH OF THE CALENDAR OF MINOS.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16

Features

-

Feature

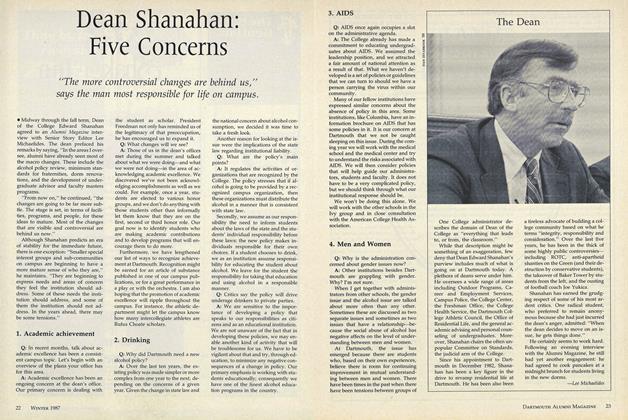

Feature2. Drinking

December 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJames Forrestal 1915

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

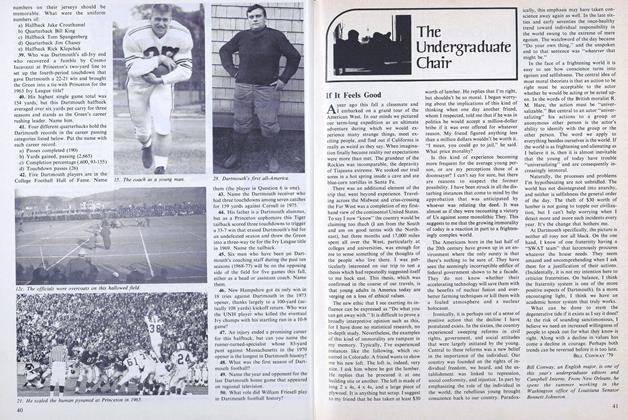

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Cover Story

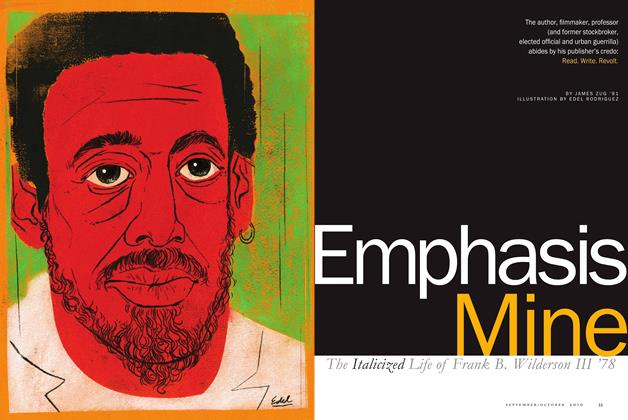

Cover StoryThe Italicized Life of Frank B. Wilderson III ’78

Sept/Oct 2010 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobinson's Undoing

MARCH 1995 By Pam Kneisel '76 -

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

NOVEMBER 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44