CONSIDER their fortunes at the Edinburgh Festival in 1973. They arrived in Scotland with little more than a listing (along with 120 other events) in the official program of the Fringe Festival and an assurance that a performing space had been reserved for them (to rent at their own expense). They found themselves in a school gymnasium with no stage. They trucked a stage from Glasgow. Unknown but undaunted, they rehearsed in the public parks by day and posted bills by night. They printed their own tickets and took them at the door. When they opened, the house was only half full. Within a week, however, the press had discovered "one of the most unusual and promising dance groups to visit this country in some time" (Daily Telegraph), and more seats had to be shipped from Glasgow. Princess Margaret, on holiday nearby, made a surprise visit to town to see their show. Like a fairy godmother among elves, she stayed to share a basket of refreshments with the dancers and to approve their projects. On the night of their final performance, their 18th in 20 days, Pilobolus Dance Theater, from Vermont, U.S.A., was awarded TheScotsman's coveted Fringe First Prize. They had come as a sideshow from the boondocks and had almost stolen the circus at Europe's greatest arts festival. Astounding. But for Pilobolus, not unusual.

When Pilobolus returns to the Hopkins Center for two performances this month, Dartmouth will be able to take, as no other audience can, the full measure of its success. A dance with the curious but prophetic title "Pilobolus" had its world premiere on the stage of the Hop's 12:30 REP series of student performances six winters ago. The three Dartmouth seniors who choreographed and danced it, Moses (Robb) Pendleton, Jonathan Wolken, and Steve Johnson, all members of the Class of '71, had been studying dance at Dartmouth for only one term.

In Alison Becker Chase's studio course in modern dance, students had to work from whatever movement backgrounds they brought to the class. "She made us use our bodies creatively right from the start, made the greenhorns dance," says Pendleton. "There's a limit to how much technique can be taught to a group of muscle-bound beginners. But anyone can try his hand at choreography, right boys?" explains Chase with a glance at the former students whose troupe she joined in 1973. As their term project, Pendleton, an English major, Wolken, a philosophy major, and Johnson, bound for medical school, decided to create a dance together. Uncertain how to go about it, they began by leaning on each other, as if to support one another's inexperience. Then they locked arms. Over the back of one went the feet of another. And another. Four legs unfolded in the air. Drawing on what they knew of yoga, mime, music, and dance, and what they soon discovered about building shapes with three linked bodies, the trio produced "Pilobolus," 11 minutes long. Those who lingered over lunch instead of taking in "Choreographic Collections" at the Hop at term's end missed out on history.

Alison Chase chose "Pilobolus" to represent Dartmouth at a modern dance performance symposium at New York University in the spring. There New York choreographer Murray Louis saw the piece and was so taken with it that he arranged a special performance before his own company. Louis and his dancers encouraged the visitors to keep on dancing. Johnson went on to medical school, but Pendleton and Wolken persuaded two fellow Chase students, Robbie Barnett '72, a visual studies major, and Lee Harris '73, a math and computer science major, to join what was then little more than a dance and a name.

What's in the name? "At first, it was just sound, just bubbling syllables," says Wolken, who recalled the word from research he had done in photobiology. Pilobolus (in real life) is the name of a genus of vigorous, light-loving fungi (which thrives on horse manure) known to mycologists for its ability to hurl its spores vast distances around the barnyard. "Later, we realized just how appropriate it was."

One of Pilobolus' first professional appearances took place at Smith College. Both offbeat rock star Frank Zappa and the crowd of 3,000 that had turned out to hear him play were surprised to see, in place of a local warm-up band, three men clad head to toe in leotards and wearing aviation goggles walk out on stage. There were catcalls. Then, as three bodies unfolded their time-lapse flower, silence, save for the eerie electronic score created for the piece by Dartmouth composer Professor Jon Appleton. Eleven minutes later, wild applause. On the spot Zappa asked the dancers to warm up all his concerts, beginning with one the following evening at Carnegie Hall. With the cheers of 3,000 throats still sounding in their ears, and a prior engagement at Hampshire College the following night, Pilobolus turned Zappa down and elected to go its own way.

The four Piloboli settled across the river from Hanover in Norwich. While Barnett and Harris led double lives as dancers and full-time students, Pendleton and Wolken devoted their energies to nursing an undergraduate enthusiasm into a professional career. Dartmouth provided after-hours rehearsal space in Webster Hall and Rollins Chapel. As the night watchman made his rounds, "Spirogyra," "Ocellus," "Walklyndon," and "Geode" took form.

When Pilobolus made its New York debut in December of 1971, at the LouisNikolais Dance Theater Lab, the New York Times was watching. A long review praised the group's physical fearlessness, humor, and inventiveness: "amazing," "astounding," "extraordinary." Those adjectives led to bookings throughout the East on weekends and between school terms. Harris's Senior Fellowship in dance enabled the group to tour more widely the following year, and success toured with it. In 1973, Pilobolus decided to increase its numbers and (like Dartmouth) to admit women. Alison Chase left her faculty position to join her progeny. Martha Clarke, wife of sculptor Philip Grausman, Dartmouth artist-in-residence in 1972, was also asked to join. Both women had had previous experience dancing professionally. Soon "Ciona," for six, was in repertory, and Pilobolus was flying to Edinburgh.

The dancers have since toured Europe five times, with several side trips to Africa and the Middle East. They have made only one change in personnel. When Lee Harris left to return to computer work, the company was fortunate in finding Mike Tracy '73, yet another Chase student and a Senior Fellow in social psychology, to replace him. In 1974, the group made a film, Pilobolus and Joan, for PBS's experimental video series. PBS cameras will record Pilobolus' Hanover homecoming for a special to be aired in April. In 1975, Pilobolus won the Berlin Critics' Prize. Last year they filled the Espace Cardin in Paris for an entire month. One evening, as they came out to take their bows before a standing, clapping crowd, they recognized ballet star Rudolph Nureyev in the front row. To the delight of the dancers and the audience, Nureyev returned their bows. Last July, Pilobolus was the rage of Italy's Spoleto Festival. In the program notes for the festival, Clive Barnes of the New York Times called them "the most original company of the decade," an opinion he confirmed in December when he listed Pilobolus among America's leading dance troupes for 1976.

Dance companies do not normally spring up and flourish like mushrooms. But Pilobolus (in addition to being named for a mushroom) is an anomaly among dance companies. Ordinarily dancers spend years, not months, acquiring technique before going professional. It is unheard of for dancers to receive their training exclusively in the Ivy League. (Incidentally, Dartmouth in 1969 was the first of the Ivy schools to offer studio dance courses for academic credit.) Almost never do they choreograph all their own material. New groups are usually born in New York, not in New Hampshire. Men rarely outnumber women. But Pilobolus has made its dances and its name by turnins convention on its head.

"In a way, we invented Pilobolus by accident. like the vulcanization of rubber. But we'd all been working toward it without knowing it," says Barnett, who had been an Outward Bound instructor and sculptor Grausman's assistant. Wolken was a fencer and had led community classes in folk dance. Pendleton had been a skier and a Dartmouth Player. Johnson was a pole vaulter, Harris a diver and a gymnast. Tracy could walk up stairs on his hands and juggle (though not at the same time). It was natural that, especially in its early stages, the Pilobolus style should draw on the dancer's muscular strength and athletic coordination. Even their relative ignorance of classical and modern dance worked in their favor. By beginning almost ab ovo, Pilobolus was able to be radically innovative in its approach to movement. "We were like an isolated population free to develop its own mutations, like Darwin's finches," comments Barnett.

The particular strain of movement that Pilobolus has evolved is emphatically physical. In "Ciona," for instance, three of the men lock right arms and turn rapidly about an axis. From the wings of the stage bound the three other dancers, who leap headlong for the free elbows. of the spinning group at the center. As they latch on, they are swung off into orbit and are kept whirling like propeller blades by centrifugal force. Suddenly the pinwheel flies apart to become a whip and a sling which sends Clarke soaring like a shuttlecock. The company is not always so hyperkinetic. The four men dance "Ocellus" as a frieze of flowing statuary. In some dances they are content to grow like embryos or sprouting seeds or to root themselves like polyps on the ocean bottom.

All dance is more or less physical, of course. What distinguishes the Pilobolus style from that of conventional dance is not just the degree of physical power involved, but the way in which bodies are linked together to harness it. "A plane surface is convenient to stand on, but not always interesting to move from. So we try to work off each other instead of from the floor," explains Wolken. "They are human tinkertoys," wrote a Boston reviewer. Centaurs, fountains, Grausman grasshoppers, catapults, airborne bicycles, colonial algae, giantesses (in full-length dresses), London Bridges (falling down), the Beast of Revelation: there is no end to their tinkering.

Classical ballet grants to the body a certain integrity. Pilobolus takes the body apart limb from limb, so that even a solo may give the impression of being danced by a group. Pendleton performs a remarkable section of "Monkshood's Farewell" while standing unshakably on one leg. His arms, his torso, and his other leg seem to move independently of the pedestal that supports them. Pilobolus undoes the traditional hierarchy of bodily parts. In Barnett's "Geode," for instance, the great toe (unpointed) and the belly (protruded) play leading roles.

When its particular idiom is compared to the learned languages employed by ballet and by some contemporary companies, Pilobolus seems to speak in the vulgar tongue. However demanding in execution, the dancers' movement is always suggestive of universal human motions. They have brought to the often hermetic world of dance the discursive approach of the liberal arts: nothing human is alien to them. One college reviewer called them "demigods"; the critic for The NewYorker noted in them a certain "goatishness." Like the universal man of Pico's famous Renaissance oration, Pilobolus even appears able to express the brutal and angelic natures.

Thus the sublime does not exclude the ridiculous. "Walklyndon" is a very funny dance based on the everyday encounters of passersby — in a street where Keaton and Chaplin have also walked. Other dances seem to represent the movements of the breast or of the mind. In Pendleton and Chase's "Alraune," the heart beats at arm's length. In "Hedgemustard's Rhume," three dancers dream up enigmatic images mounted by the other three. For the imagination itself, that faculty of the mind which classicly joins unlike shapes together and causes dreams, Pilobolus' coupling techniques supply a precise metaphor. The dancers themselves sometimes seem to represent the animal spirits at play.

It is hard to say at what point dance becomes mime. In any case, Pilobolus has never bothered about the distinction. In "Pilobolus," the dancers seem to explore an alien world, another planet or a drop of pond water. At moments they assume vaguely familiar shapes or poses, then retreat into the safety of geometric abstraction. As the company has matured, however, particularly through the addition of the women, it has increasingly given play to free dramatic fantasy. "Monkshood's Farewell," for example, is a carnival of medievalia. Knights joust with exaggerated ceremony. Queens are borne in on the backs of elephants. A winged creature kills with its look, like the mythical basilisk. Pilobolus' plots and images are as elusive as they are suggestive. It is impossible to fix them without spoiling the riddling or figurative character they have in performance. "Dance metaphor thy name must be Pilobolus," exclaimed Clive Barnes.

E pluribus unum: Pilobolus has twelve legs but one soul. The intensity of their conceptions and the rapport the dancers exhibit among themselves in performance are directly attributable to their unorthodox methods of choreography. The group has no artistic director. They create their works collectively, relying on each other's comments and on videotape to polish them. Decisions are made only by acclamation. Says Tracy: "Rehearsals are often emotionally trying. Six imaginations collide. At first, there's a chaos of selves, but it ends in interdependence within a group."

When I visited the Piloboli recently in Washington, Connecticut, where they now live and work, they were putting a new piece together. A section was being choreographed for Chase and Wolken. It sounded something like this:

"Let's run through the dolmens."

"Try the step-up. Crane your neck, Finn."

"Goose goose goose."

"Take it easy, Queen, head back."

"But we're putting that in the Blatant Beast."

"No, that's out."

"Jump up and then perch."

"I don't like it. You've both got to be off balance."

"A monolith off balance?"

"This whole section is absurd. Back to the rockpile."

"Let's run through it again." Pilobolus is anything but a clone of identical individuals. "Like it or not," says Tracy, "we always begin with human relations. We resolve our differences — and celebrate our affinities — in a group personality." "It's like parenthood," says Martha Clarke, mother of an eight-year- old son who is himself a seasoned bit performer with the group. The result is dances that are always emotionally plausible and dancers who appear perfectly cast for their parts.

The excitement that Pilobolus' public performances generate is another matter. "In the late sixties," says Pendleton, "many theater ensembles left the proscenium in order to come into closer contact with the public. But audiences were not always prepared for the assault, and art was often sacrificed to politics. We decided to remain on stage but to project our energy very consciously outward in the hope that audiences might feel the intensity of participation simply by being present." On stage or off, the Piloboli are natural showmen. So infectious is their enthusiasm for their art that virtually anyone who sees Pilobolus, catches it. Their wit engages the intellect. Their contortionist's tricks involve the viscera. Their exuberance and festival good humor draw the audience to them, naive and sophisticated alike. Like a court revel or the Great Nature Theater of Oklahoma, Pilobolus includes everybody. One leaves a performance with spring in one's step, an agreeable giddiness in one's head, and generosity in one's spirit.

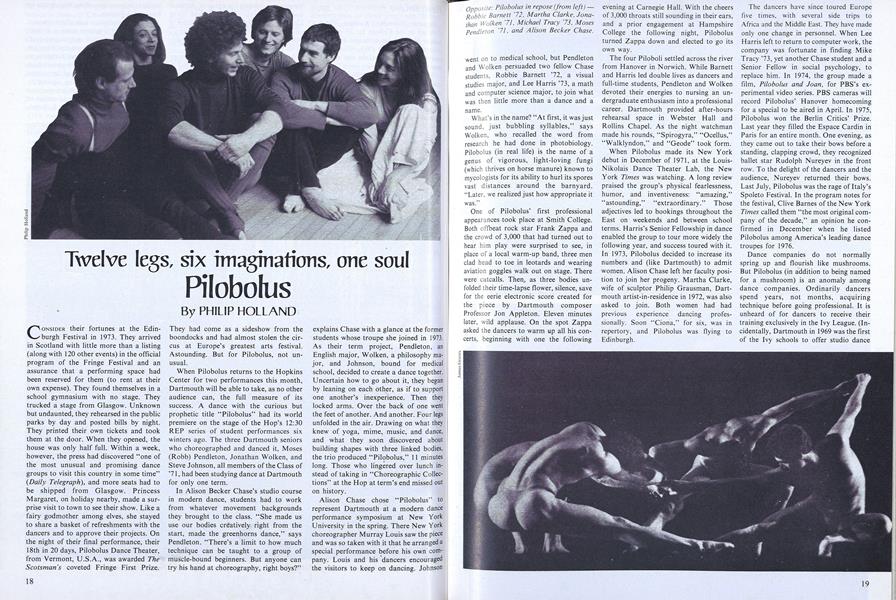

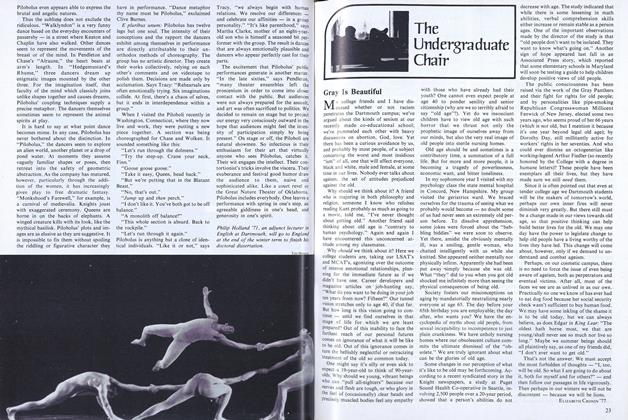

Opposite: Pilobolus in repose (from left)- Robbie Barnett '72, Martha Clarke, Jona-than Wolken '71, Michael Tracy '73, MosesPendleton '71, and Alison Becker Chase.

If you miss Pilobolus in Hanover, yoube able to see it in Paris, London,Istanbul, and Australia in the comingmonths. PBS will devote an entireprogram of its Dance in America series toPilobolus for broadcast the 27th of April.

Philip Holland '71, an adjunct lecturer inEnglish at Dartmouth, will go to Englandat the end of the winter term to finish hisdoctoral dissertation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

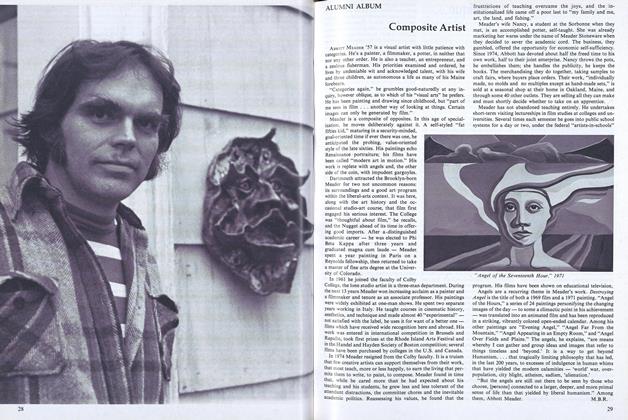

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77 -

Article

ArticleBittersweet Memories

February 1977 By ROBERT J. ZOVLONSKY '58

Features

-

Feature

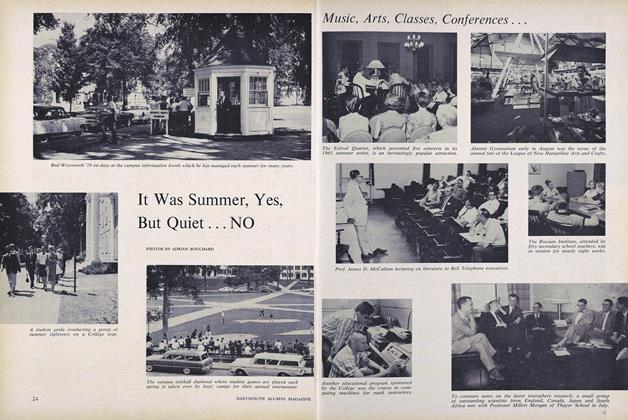

FeatureIt Was Summer, Yes, But Quiet... NO

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

OCTOBER 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

DECEMBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

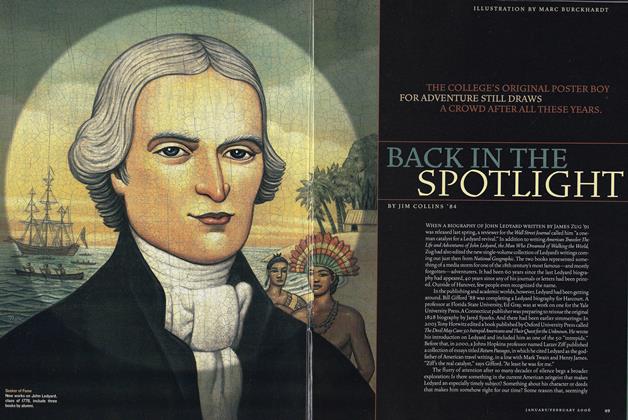

FeatureBack in the Spotlight

Jan/Feb 2006 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

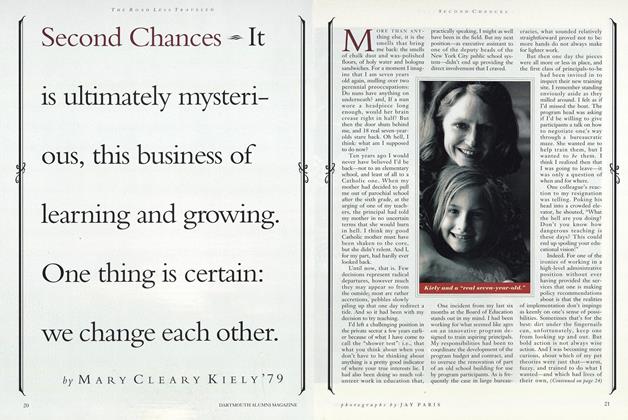

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79