President Dickey's Convocation AddressOpening Dartmouth's 189th Academic Tear

WE gather this morning in an unusual setting for this ceremony opening another year of Dartmouth's immortal corporate life. A week ago last Saturday night this lower area of. Alumni Gymnasium was filled with an international throng of several thousand people gathered under these 81 decorative flags of the United Nations and under the aegis of this magnificent five-fold emblem, created by John Scotford of the Class of 1938, symbolizing the Dartmouth Convocation on Great Issues in the Anglo-Canadian-American Community.

We are meeting here today rather than in the all-too-limited facilities of Webster Hall in order that as many members of the College community as possible may touch and sense at least momentarily something of the alternating forces of independence and unity which within the context of three wonderful days of creative discussion made history both here and beyond Dartmouth. This special Convocation marked both the tenth anniversary of the Great Issues Course and the mid-point between twelve years of postwar Dartmouth and the twelve years ahead as this College enters a unique period of sustained planning aimed at bringing it to a running start of preeminence in all respects when it enters its third century of educational service in 1969.

Last year on this occasion I spoke with you about the task of achieving your own individual independence while coming to at least tentative terms with one community after another. I suggested to you that "Dartmouth is where you will cross the threshold of independence to something larger." This morning I want to move across that threshold and suggest to you that the largest realization of all independence is a creative man, a man who one day leaves behind him a sum greater than the total of his inherited qualities and fortuitous fortunes.

The aim of all true education is to give man a creative relation to life. It is creativity alone that enlarges understanding, multiplies the wealth of nations, improves the weapons of war, fashions the ways of peace, and endows man with his civilizing hallmarks - a love of beauty and a will to truth.

We often hear it said that training is not education. Have you ever paused to ask yourself whether and why this is true? It is a useful thing for both a teacher and his students to be clear about. For my part I believe the essential difference between training and education is that training seeks reactions in a man which will reproduce images, beliefs and ways of doing a thing, whereas education seeks to kindle capacities in a man for producing a creative relation to his life and work.

This is not to say that training is not a useful and necessary thing in making one's way. There are many points in any life where life itself may turn on a man's having learned how to reproduce a thing. Being able to make a fire was not the least of such things for ages and ages and yet there would be quite a few cool corners in this gymnasium come January if man had never risen above reproducing fire from the sticks which kept Wheelock's log cabins liveable - most of the time. We hardly dare speak of the latest things but the need of good training and its place in education is made painfully real by asking how many of us today can reproduce electric fire, let alone the nuclear fires of atomic fission and fusion?

WHAT can usefully be said here about the nature of the creativity at which education aims? We may do well to begin by admitting that in any form creativity is rarely prescribed as a tranquilizer. It is the enemy of sustained repose in a man or a society.

It put buggy whip manufacturers into bankruptcy; it turned wagon makers into automobile dealers; it periodically turns upside down the learning and practice of the ancient profession of medicine; it performs endlessly the miracle of the loaves and fishes to supply an exploding world population with food and energy in ever more fantastic forms and portions; it provides the means whereby that world in its snarling quarrels over this same food and energy will some day either produce enforcible peace or a deathly quiet earth; it puts nice people at other people's throats over politics, philosophy, religion, music, art - even architecture. And redemptively it contributes to the fun and sanity of life by providing fresh jokes about the advantages of leaving your mind alone.

These things and all else like them were produced not by the word progress but by the creative ferment of restless minds. Creativity may not always produce progress, but granting the possibility of progress, as most Americans surely do, is there any progress that in the plainest and most literal sense was not created? Surely, if it is progress or a true enlargement of human experience it was not copied.

A creative relation to life is not limited to those few men and women who have it in them and whose good fortune it is to accomplish one of the great discoveries of human experience. This sort of breakthrough is creativity with a capital "C" and all of us, in our Walter Mitty moments, can at least imagine the thrill that comes to a man who lives to know that he has created something important that was not a part of the human heritage before he came along. The point I want to leave with you this morning, however, as we begin another year of Dartmouth's work is that the bet of education is not merely or even mainly on the great ones. They usually set a pace of their own and the problem of the College is to give such front runners their head without having everyone else conclude either resignedly that things of the mind are only, as the phrase goes, "for the brains" or, worse, are to be left in contempt "for the birds." Gentlemen, either of these attitudes is at best a denial of a man's right to be here and at worst it is a betrayal of self that is likely to bedevil a man the rest of his life until even the birds turn up their beaks at his shriveled soul.

No, the truth is that while creativity spelled with a capital "C" is rare, the opportunities for lower case creativity are potentially unlimited in every life and it has been the historic function of education in the liberating arts to free men, one by one, for the fullest possible enjoyment of these opportunities.

The great creators sometimes seem to stand alone and unexplained like Monadnocks surrounded only by plain, yet the more we know about such discoverers, the clearer it is that they like the rest of us are standing on the shoulders of those who went before. Whether one of you will someday be such a great one none can now know, but this we do know: for the sake of your own life, that it may have its own great moments of meaning and joy, even the least of us must turn himself toward the sun. And after all, what mortal dare measure the difference in deep satis-faction between two men's best? The words of Mr. Justice Holmes provide each of us with enough of a foothold for the climb ahead: "When a man realizes a truth he feels as if he had discovered it."

Whatever you may or may not produce for others, do remember this - to appreciate is to create for yourself.

I trust it is not necessary for me to labor the point that the creativity of which I speak is not talent reserved only to the world of writers and artists. The quality of mind and of doing of which I speak is found in every walk of life, it lights up the lives of businessmen, statesmen, teachers, preachers and football coaches as well as artists, scholars, musicians and writers. And lest I am still misunderstood by some, it might be added that the world today usually (not always to be sure) pays for creativity in coin of the realm, sometimes very well and almost always eventually in honor, the coin of history.

Robert Frost talks about it when he counsels all of us to "get something up for yourself." The teacher sees it in the student who gradually builds up his own muscles of understanding and enjoyment by straining to lift the knowledge created by others. After all is read and said and all the blue books are written and marked only that which has been wrestled by you into your own experience has been learned. The rest is that kind of pseudowrestling well described as "throwing the bull" - a boring spectacle although regrettably not a notably tiring exercise.

A N enterprise engaged in the business of educating men for a creative relation to life has especial need to be creative in its own outlook and work. During the past two years Dartmouth has been engaged in a comprehensive review of her educational program. The objective of this review has been to bring our curriculum, our teaching and our facilities to a fully concerted impact on the main purpose of the College - your education.

There is no need to review here the details of the projects to this end which were announced last fall and spring. The full impact of these projects will not be realized for some years yet, but in the very real sense that every today is in part both yesterday and tomorrow the influence of these undertakings will be felt immediately and increasingly from here on.

The new three-term, three-course arrangement of the curriculum will go into effect a year from now and already faculty members are at work planning revisions of many courses. It is certain that indirectly, if not directly, these plans will often be reflected in this year's classroom work.

But I am sure most of my colleagues in the faculty would want me to say that important as the new arrangements and course revisions may prove to be, the most important feature of the new program is its pervasive concern for shifting the emphasis in college from a student's dependence upon teaching to his reliance upon independent learning. All else in the new program is anchored by this principle.

It hardly needs saying that here is an aspect of tomorrow's plans which ought to go into effect today wherever it was not in effect yesterday. Progress in giving effect to this fundamental principle will require the utmost in creative responsiveness from both student and teacher. Manifestly it means harder work for the student who has been leaning too heavily upon the teacher and doing no more than the minimum necessary for "getting by," but paradoxically it also means more work for the teacher. It is usually easier to instruct a student than to stimulate and lead him to independent learning. And any good teacher will tell you that keeping out in front of a pack of really hungry students is about the best exercise there is for the mental waist line.

An educational program designed for learning requires first-rate facilities as well as the best in teaching and a curriculum. We have all heard the phrase "bricks and mortar" used with an easy contempt, and so long as the reference is not to the roof over our own head, we usually nod with an equally easy agreement. Whether the agreement be easy or not, I am unequivocally clear that whenever choice must be made in education or elsewhere as between facilities and men, the decision must be in favor of the human element, if for no better reason than that men produce facilities, but there is no viceversa here as in the case of chickens and eggs.

Would we not also all agree, however, that any man or any enterprise that must choose between essential ingredients of strength is not a candidate for true greatness, let alone preeminence? The college that must long make choices as between men and facilities will soon find it has done so at the ultimate expense of both. The price of greatness is never stated in one or the other of two essentials. For us it means both first-rate men and first-rate facilities. In a word this is why Dartmouth today asks all who care deeply for her greatness to stand shoulder to shoulder in her first Capital Gifts Campaign as an essential part of her 200th Anniversary Development Program.

Yes, men produce facilities and the goal on this side of things is to create facilities which will themselves be creative in advancing our educational purposes and in compounding our teaching and learning efforts. Dartmouth's superb Baker Library is such a facility and our aim must be to gird the other aspects of the College's life and work with comparable strength. On the fronts of faculty and student housing and eating facilities we have made solid advances the past two years. During the coming year we will bring into use four new dormitories specifically planned to make a positive educational contribution as well as house three hundred students from what I trust will soon again be a series of truly ancient old-fashioned winters.

The group of four major building units which are embraced in the over-all concept of the Hopkins Center project will go far to meet our most acute educational plant needs for instruction, creative arts work and fellowship purposes. These units will give us two critically needed classroom-lecture facilities with modern visual presentations for groups up to 900 and 450 respectively. They will meet perhaps the most long-standing and serious educational deficiency of this liberal arts campus - first-rate theatre facilities. They will give a home to our chronically peripatetic musical groups for both practice and performance. They will bring together in useful proximity and central focus Virgil Poling's student and faculty workshop (now facing its last year in its perilously disintegrating attic quarters of Bissell Hall), the painting and design classes of Paul Sample and Richard Wagner, and the graphic arts workshop of Ray Nash activities which together annually touch and enrich the educational experience of several thousand students, faculty and townspeople of the Dartmouth community. They will bring the College's art collections from their third floor hideout to ground-level accessibility, free the old space for instructional work and make it possible for Dartmouth in the future both to avail itself of rich travelling exhibits and to build up its needed permanent collections. Finally, this Center will provide students, faculty, alumni and other visitors with fellowship facilities for informal sociability, meetings, dances, dinners, receptions, reunions - needs which I know you will agree have become dangerously acute on this outpost campus within the past decade.

These dozen or more specific uses will be tied together within an over-all educational arrangement and a planned integration of the major units which both our people and outside educators believe will make this Center one of the most creative physical facilities ever devised to extend and enrich the daily educational impact of a liberal arts college on all of its constituencies, teachers and learners alike and together. Here, as in the Agora of ancient Athens, there will be a physical focus for bringing together in daily life the work and the significance and the joy of an existence fully realized in independence because it is creative.

GENTLEMEN, all experience teaches that the joyful moment is the created one but let us never forget that it is an earned joy because as the Book of Genesis makes clear, even the Lord found the creation of things rather strenuous work.

To the men of the Class of 1961, within whose college careers these things will be most fully realized, I extend the Dartmouth greeting: You are more than welcome, you are now one of us. To all of you I pass on for its creative perpetuation the accolade spoken from this spot by the Prime Minister of Canada in tribute to the embracing creativity of this educational enterprise: "Dartmouth College has become a cathedral for freedom."

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

The opening exercises this year were held in Alumni Gymnasium, in the flag-decked setting of the Dartmouth Convocation on Great Issues in the Anglo-Canadian-American Community.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHanover in the Ice Age

November 1957 By RICHARD J. LOUGEE '27 -

Feature

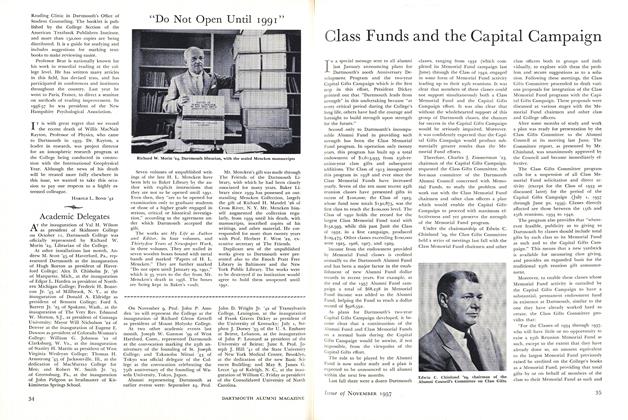

FeatureGlass Funds and the Capital Campaign

November 1957 -

Feature

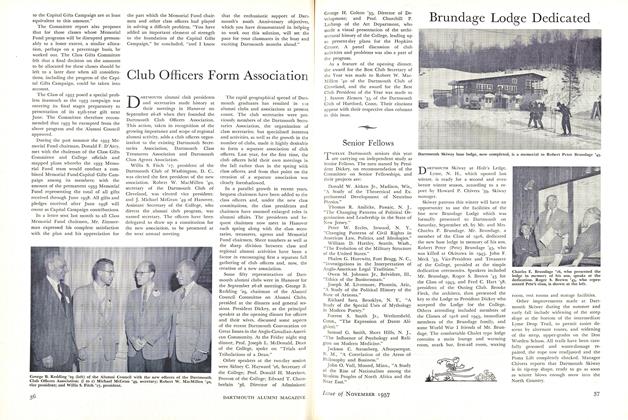

FeatureClub Officers Form Association

November 1957 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

November 1957 By WILLIAM L. CLEAVES, F. STIRLING WILSON, RODERIQUE F. SOULE1 more ... -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1957 By DONALD BROOKS, VICTOR C. SMITH, GILBERT N. SWETT

Features

-

Feature

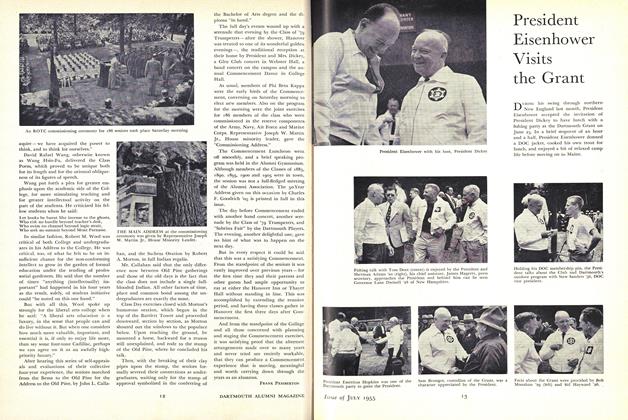

FeaturePresident Eisenhower Visits the Grant

July 1955 -

Feature

FeatureRevival of the M.D. Degree

APRIL 1970 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's 214th

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Doug Greenwood -

Feature

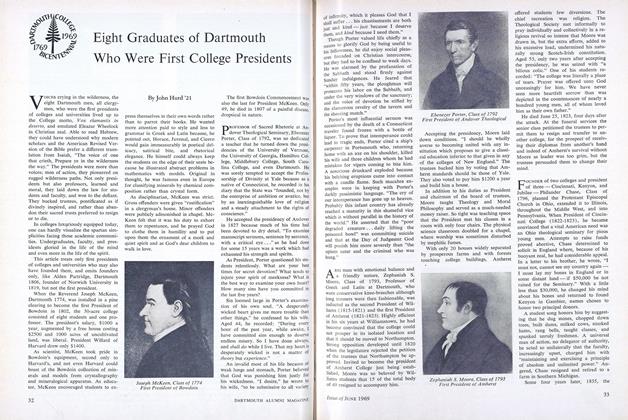

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

JUNE 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Cover Story

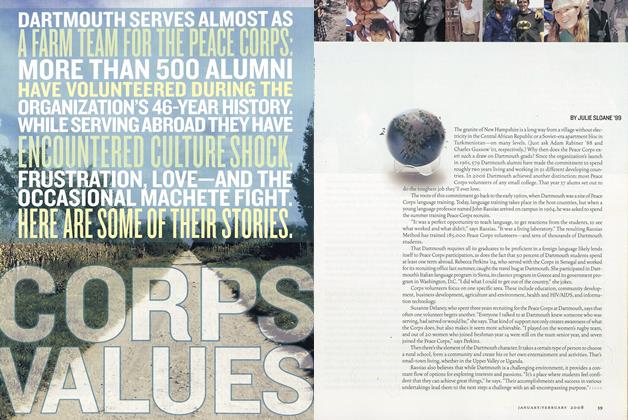

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Cover Story

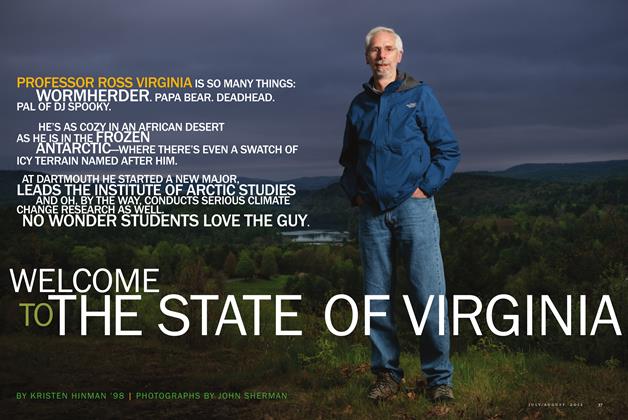

Cover StoryWelcome to the State of Virginia

July/August 2012 By KRISTEN HINMAN ’98