There is something about the quiet good men that makes them difficult to properly praise. You sense, most of all, that they really don't want the attention.

So it is with Clifford L. Jordan '45. He doesn't talk about himself much, and is quick and deftly practiced at turning the spotlight to others. But when Cliff retired from his sweetsmelling, pipe-smoky corner office in the Blunt Alumni Center this June, just a few days shy of his 62nd birthday, he had completed 34 years of service to the College, a full 30 of them in the Alumni Fund Office. There are those who will tell you that when it comes to Dartmouth alumni relations, Cliff Jordan helped write the book.

"I think he's probably the best nuts and bolts professional in fundraising I've ever known, and I mean that as the highest compliment," says Ort Hicks '21, himself one of the guiding lights of Dartmouth affairs for many years. "He's a man who knows what you should do, when you should do it, and how. Cliff Jordan is tops."

Another Jordan fan is Allan Dingwall '42, an associate of Jordan's for the past 14 years. Dingwall credits Jordan with being the prime architect of what is currently the most successful alumni fund among all American colleges and universities.

"More than any other individual, Cliff can claim responsibility for establishing the basic structure of the Dartmouth Alumni Fund/' Dingwall said. "It was his care and attention to detail, plus enormous creative ability, that has given structure to the Alumni Fund. His is a masterwork."

Jordan, of course, won't hear any of it. He points to classmate Nick Sandoe, to George Colton '35 and to his personal hero, John Sloan Dickey '29, as the muscle and brains that made the Fund work. As far as his own accomplishments are concerned, Cliff's summary is characteristically modest. "I've survived and I've had fun," he says with a laugh. "And I've met so many good people along the way."

The way to Dartmouth was by no means a certain thing for young Cliff Jordan. At the Roxbury Latin School in Massachusetts, where Jordan prepped, the tradition was for its graduates to enter Harvard. As the son of an accountant father and poet/housewife mother who early on fired her son's literary desires, Cliff was a good student, an editor of the school magazine and a third-place finisher (at 145 pounds) in the state wrestling tournament. When his class of 23 entered college, 17 followed the well-worn path to Cambridge. Jordan chose Dartmouth.

"I don't really know why," he says now. "I guess I just didn't want to follow the crowd."

At Dartmouth Cliff played freshman football, wrestled, worked at the D, and then enlisted in the Army Air Corps during World War II. By V-J day, he had made staff sergeant, serving as a flight radio operator and aerial gunner aboard B-255. The war years did not pass without interest for Jordan. As a combat crew-instructor at Selfridge Field outside of Detroit, Jordan helped train the very first Negro bombardment group ever assembled.

"These fellows are all fine, earnest students," Jordan wrote on USO stationery to his class newsletter editor back in Hanover, "and they should make a cracker-jack record in combat."

Another matter of consequence for Jordan was his marriage to Roberta Elizabeth Meade of Portsmouth, Ohio. "I met Betty while I was stationed at Godman Field in Louisville and she was working in a war plant in Cincinnati," Cliff remembers. "We'd been going out for 18 months, a war was going on, and we were in love. So we got married. That was almost 40 years ago, and she is still the best thing that ever happened to me."

Cliff and Betty returned to Hanover in 1946 with newborn son Richard. Jordan finished his A.B. at Dartmouth in 1948 and took a job with the Peddie School in Hightstown, N.J., as a history teacher. But teaching just wasn't in the cards. "I'd been hired to teach, and that was what I thought I most wanted to do," Cliff says. "But the development director discovered I could write, and he moved me into public relations. I found I liked it."

Jordan not only liked PR, he was good at it . . . good enough for Dartmouth to hire him in the fall of 1950 as assistant director of News Services. That job branched out quickly to include press releases for the DCAC, and Jordan's skill at that task landed him the position of director of sports information in 1951. "Back in those days, Winter Carnival was a big deal all over the country," Jordan explained. "Those were also the same years that television was coming into its own. The very first TV crew that ever came to Hanover came up to film some footage of Carnival, and it was part of my job to help them out. Of course, it didn't help much that I didn't know a thing about television!"

Jordan learned fast. Partially as a result of his efforts, the very first national broadcast of an NCAA football game in the fall of 1953 featured Dartmouth versus Holy Cross, live from the Manning Bowl in Lynn, Mass. Unfortunately for Dartmouth, a big slashing back named Omanski led the Crusaders to victory that day. But history had been served.

Back on the Hanover Plain, Cliff's career took another decisive turn. In 1953, he became an associate of the annual Alumni Fund, in 1955 an associate in the Office of Development. The die, as they say, was cast.

To recount 30 years of work with the Dartmouth Alumni Fund in any detail would require the addition of another stack at Baker Library. But it is safe to say that Jordan either helped implement or personally directed just about every major change in the College's annual giving effort. Jordan came on board when the Fund raised less than $1 million, and has had the satisfaction of retiring after playing an important role in helping the 1984 campaign shatter the $10 million mark. Cliff was there when the first capital gifts campaign raised over $17 million between 1957 and 1960, and he was one of the linchpins in helping the Third Century Fund reach its goal of $51 million.

But there is much more to the measure of Jordan's successes at Dartmouth than a mere rehashing of numbers. He has worked intimately with some of the finest men the College has ever produced, including Trustees Charlie Zimmerman '23, Rupert Thompson '28, Ralph Lazurus '35, Sandy McCulloch '50, and Dick Lombard '53. Cliff fondly recalls the efforts of individuals like Al Louer '26, a head agent for 25 years; Ford Whelden '25, originator of the Century Club and founder of the bequest and estate planning program; and Fran Fenn '37, perhaps the most well-traveled volunteer on behalf of Dartmouth in the College's long history. Jordan counts them and many others as friends, then begins adding names such as Winship, Breed, and Eberhardt. The list, it seems, is endless.

And through all of this dedicated and highly successful work, Jordan has silently displayed the sort of courage that marks the truly strong. For since 1972, Cliff Jordan has been legally blind. He suffers from a hereditary disease Retinitis Pigmentosa a condition doctors discovered he had when he returned to Dartmouth in 1950. This rare disease, which causes a gradual degeneration of the retina, skips every other generation and is transmitted through females. "I had three sons," he says gleefully, "so the damn thing ends with me."

It is, however, just a matter of time before Jordan's world becomes completely dark. Even now, he has an extremely limited cone of vision through the left eye. Yet to watch him do his work and banter about the halls of Blunt, you realize that his handicap is a thing that Cliff Jordan spends precious little time worrying about.

"I've been fortunate to be at Dartmouth while all this was happening, among my friends and in a familiar place," Jordan says. "I'm sure my near-blindness has been more trouble for others than it has for me at times, and I can't thank the people who've helped me enough. No, I don't like it. But things could be a lot worse."

Cliff and Betty are planning on taking some extended trips after Dartmouth, visiting family and friends. Hanover will always stay a center "Gee, two of my sons went to Dartmouth, and this has been our home for so long" but the Jordans are eager to expand their horizons.

In the admissions files of Clifford Leslie Jordan, Jr. is a letter dated March 12, 1941 from Philip Fowler '27 of Boston commenting on the credentials of the freshman candidate. In understated candor, Fowler wrote on behalf of his committee: "He is the type of boy who will fit and wear well at Dartmouth, and we feel his acceptance should be recommended."

Forty-three years later, Mr. Fowler's assessment has been thoroughly borne out.

Cliff Jordan '45

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor John Stearns '16: Rara Avis Una

June | July 1984 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

June | July 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

June | July 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureThe Best Part of My Academic Life Here

June | July 1984 -

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

June | July 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

June | July 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Young Dawkins '72

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June • 1985 By Charles T. Wood -

Features

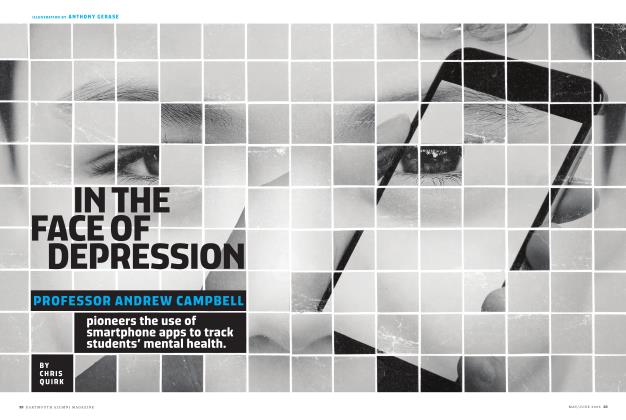

FeaturesIn the Face of Depression

MAY | JUNE 2025 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

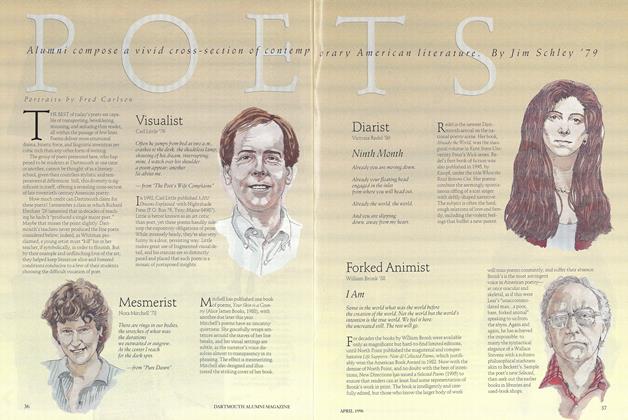

FeaturePOETS

APRIL 1996 By Jim Schley '79 -

Feature

FeatureLove and War Among the Ivies

Jan/Feb 1981 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureEducation the Groove

March 1957 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR. '52 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74