THE Dartmouth campus is a quiet, peaceful scene at 2 a.m. on a Wednesday morning. The buildings are darkened and except for the dim light in Baker Tower the landscape around the green is looked upon only by the cold starlight of a New Hampshire night. The conspicuous light still burning in the second floor of Wentworth Hall would suggest merely that someone forgot to turn it off. To the men working inside, however, it is indicative of the last-minute work of a Dartmouth Debating Team preparing to leave for another tournament.

The Forensic Union has had a long and often exciting history. Its records over the years have seemed to reach heights that could not be surpassed, but today it has attained the highest rating nationally it has ever enjoyed. A debater would not make such an assertion without trying to substantiate it, so allow me to examine briefly some of the key statistics of last year's results.

In 1956-57 the Forensic Union traveled 25,000 miles to compete in thirty tournaments against schools from 34 states plus the District of Columbia and Canada. We met 150 different schools in intercollegiate competition in these various tournaments and emerged victorious in 74 per cent of the 327 rounds of competition.

The season was climaxed by an unprecedented victory in the District Tournament, in which no ballots were cast against the Dartmouth team in eight rounds of competition; and then a fifth place in the National Championships at West Point against the top teams from the entire nation.

These few facts I put before you to set the stage for my major purpose in this article. That is to try and point out why public speaking has become an important "competitive sport" at Dartmouth. In other words, what has made it possible for the College to become nationally recognized in speech.

The attempt to isolate reasons for the success or lack of success of a program is obviously a subjective thing, and I hasten to add that this is my personal interpretation. It is based on three years of participation in speech here at Dartmouth.

The first category which immediately presents itself is the students who are involved in the program. In order for any team to win consistently there has to be a desire by the members of the group to be the best and also a willingness to make the necessary sacrifices which make a good season a reality. It is a common misconception that debating constitutes nothing more or less than a facility with words or, as the expression goes, having ample amounts "of hot air." Anyone who has ever been connected with a forensic program or has heard good intercollegiate debating will testify that this is not true. It is my honest belief that debating here in the College is the equivalent at least of carrying another course. This is a very conservative statement, and an examination of the topics debated each year proves this point. A person just does not begin to speak on a subject such as the "Guaranteed Annual Wage" or the problems of "Foreign Aid" without extensive study and preparation.

Success in debate is proportional, in large extent, to the amount of knowledge and understanding that a man has of his subject, and the fact that Dartmouth has been consistently successful indicates to me that the participants have done a lot of hard work. This, coupled with the fact that students get no extra credit for all this research, further emphasizes the interest they have and the enjoyment they must receive from this type of activity.

Another factor contributing to the victories year after year is the number of men involved in debate each year. People with whom I talk around the country are often surprised that the debate team is composed of more than just ten or twelve students. Actually, we usually have forty men competing in the varsity and novice divisions. This makes it possible to have a well-balanced team. We may have four or five top debaters graduating in June, but there are always other good men who have been able to get experience in actual competition and are therefore ready to fill the gaps created by departing seniors. As a matter of fact, we often find freshmen who are good enough by the end of their first year to hold their own with the best debaters. The object, then, of our program is not to let four men do all the debating but rather to give as many as are interested a chance to take part actively. This is the reason why the College is able to send teams to so many tournaments. Different men are traveling each week, and on one weekend last fall I remember that we had 24 men in five different cities on the same day.

Another closely related factor in the national recognition Dartmouth has received is the attempt by the Forensic Union to send its members to the better tournaments so as to give the student the best possible competition. There is an old saying that a man performs best against the best, and the record over the last six or seven years bears this out. The schedule has become more impressive each season and the won-lost record has remained outstanding. Examples of tournaments of the finest quality that were added recently are the Heart of America Tournament at the University of Kansas, which has 32 invited schools each year based on their records in their districts, and the Xavier Tournament which we plan to attend in Cincinnati, Ohio.

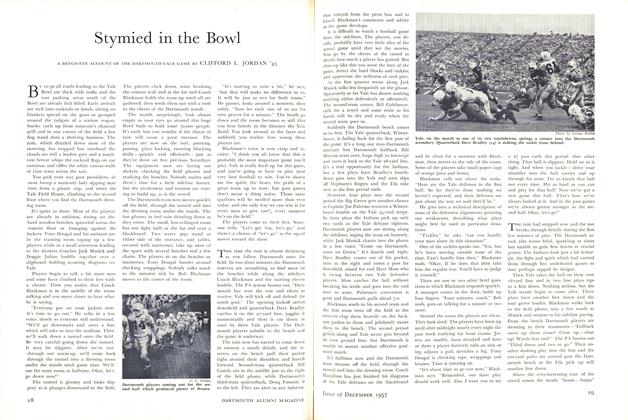

The previous comments concerning the reasons for the success of debating at the College have been personal interpretations. My final point is not one peculiar to my way of thinking, and I'm sure I speak for past and present students of Dartmouth in making it. The most important factor in our debate success is a shy, mid-western bachelor by the name of Herbert L. James, the coach of the Forensic Union for the last five years. Professor James, or "Herb" as he prefers to be called by his students and debaters, received his A.B. at the University of Wichita in 1949. He took his Master's degree at Ohio State in 1951, and has continued graduate work in speech at the University of Florida. The dates indicate that he is still a young man, but my association with coaches throughout the circuit in the last three years convinces me that they consider him one of the top debate coaches in the country. There is no more accurate way to determine a man's rating than by the words of the coaches themselves.

I could heap up adjectives but that wouldn't increase his prestige among those who don't know him, and comments of this type are superfluous to those who have come in contact with him. Instead I'd like to advance his theory of coaching debate and let you judge for yourselves. It is his contention that a debater should be thoroughly familiar with the basic principles of argumentation and debate, and as he is an authority on this subject, he insists that the entire squad be, first of all, good, reasoning thinkers. He feels just as strongly, however, that the program, to be worthwhile, must permit the students to use their own ideas of expression and thought in their arguments. In a nutshell, he wants the man to do some thinking on his own but to keep it within a logical framework.

This is a simple philosophy to state but few people realize its implications. What it really means is that he spends all his time during the debate season with the debaters. When you have forty men with forty different ideas on a topic and you have to talk to all of them at different times and discuss their problems, it is an unbelievably time-consuming and exhausting job. For example, from the first week in February to the middle of May, we have a team debating somewhere every weekend. Professor James, therefore, is traveling with one of his teams almost all of his free time.

Before you all break down and weep in protest at this cruelty, let me add that "Herb" loves this type of life; and the bond of personal friendship which has grown between him and many men has been a tribute which is hard to surpass.

It is not just coincidence that his de- baters are regularly leaders on the campus and many are scholars in foreign graduate schools. If I were to summarize the worth of this program in one sentence, it would be that the values and benefits of speech, organization of thought, and logic begin here at Dartmouth and never end.

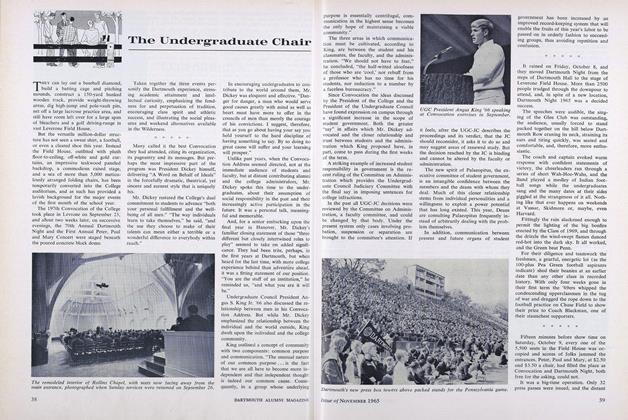

Prof. Herbert L. James of the Speech Department, who coaches Dartmouth's debate teams, and Ron Snow '58, Forensic Union president, who writes about debating as a student activity in this month's "Undergraduate Chair." Snow lives in Laconia, N.H., and attended high school there. He is president of Palaeopitus this year and is a member of Delta Upsilon and of Casque and Gauntlet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

FeatureStymied in the Bowl

December 1957 -

Feature

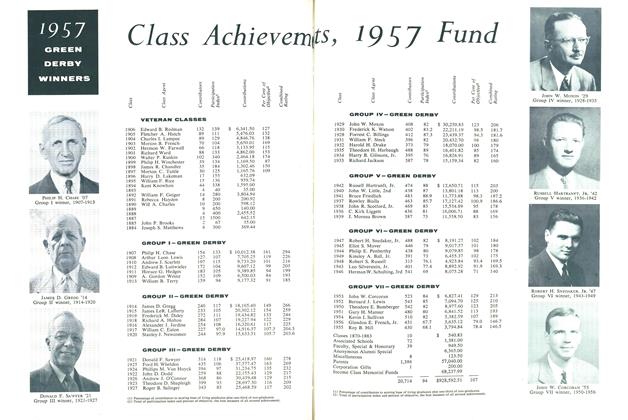

FeatureClass Achievemts, 1957 Fund

December 1957 -

Feature

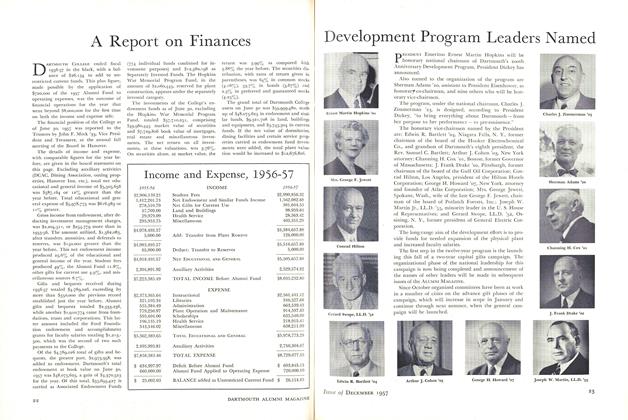

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1957 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

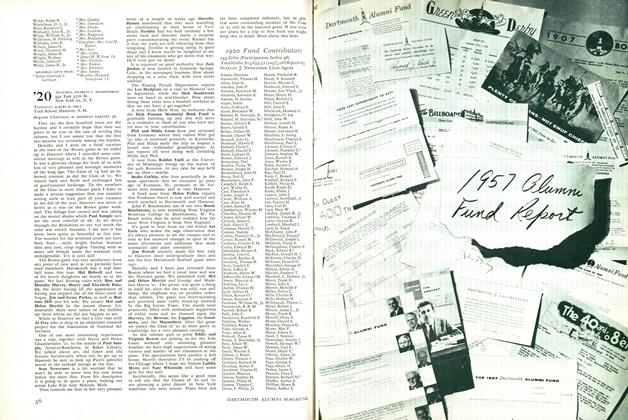

FeatureDevelopment Program Leaders Named

December 1957 -

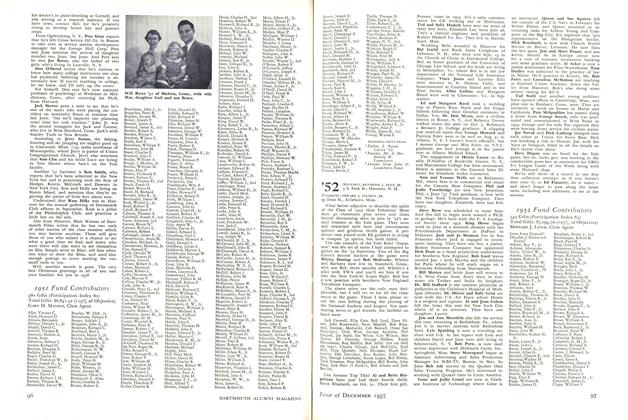

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

December 1957 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR., EDWARD J. FINERTY JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticleRECEPTION TO MAJOR REDINGTON "61 IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

December, 1923 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1940 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

December 1949 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

MAY 1986 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1965 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleStudent Scene

NOVEMBER 1993 By Nancy Davies