1713.1759. By Arthur M. Wilson. New York:Oxford University Press, 1957. 346 pp.$10.50.

This is the biography of Denis Diderot, "the mind and the heart of the eighteenth century" in the words of Paul Hazard, the "sanguineous, vehement, volatile mortal" in the words of Carlyle, the "seer" who saw "perhaps further and deeper than any other man of his century save Goethe" in the words of Arthur Wilson himself. Diderot is the man most responsible for the Encyclopedic or to give its American name the Methodical Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts,and Trades consisting of 28 volumes, 1751-1772, with a supplement of five volumes, 1776-1777, and an analytical index in two volumes, 1780. Professor Wilson's volume carries us only to the time the Encyclopedic, with volume VIII in the press, was suppressed, with financial loss of $400,000 in modern money facing the publisher, and with Diderot going underground in an attempt to escape arrest and to continue his forbidden work.

The biography should be praised first for its admirable brevity. In only 346 pages it leads us through all the early ramifications of Diderot's life to that central crisis in 1759- Aged 46, at the height of his powers, he was so harassed by authorities that, like a Hitchcock character, he had to slink down alleys by night with forbidden manuscripts and by day hide from the fetters of jailers ready to let them settle permanently on his profane hands. Repudiated by his literary collaborators, he was driven, almost a victim of Rousseauesque persecution mania, to consider hiding in some savage jungle. The final blow came when he was damned by the King sitting in benign confabulation with his council at Versailles. The revocation of the license to publish the Encyclopedic was a dagger blow to the heart of eighteenth-century enlightenment.

To Diderot the wound might have proved fatal if he had had the heart of only an intellectual predatory hawk or of a lonely eagle on a remote philosophical mountain range. Fabulously protean, Diderot proved his phoenix nature by rising from the ashes of persecution which his contemporaries, fatalistic ravens, called cold and dead.

A reviewer may also praise the kinds and usefulness of the footnotes inserted modestly in some 53 pages at the end of the book where they do not intrude on casual readers. That Professor Wilson is learned may be surmised by a reader informed of the following facts. The smallest number of footnotes for a chapter is 36; the largest, 70. There are 25 chapters. The total number of footnotes is 1,327. Every scrap of information about Diderot has been checked and properly accredited. And still the quest goes on. On leave of absence from Dartmouth, Professor Wilson, accompanied by his indefatigable research assistant, the invaluable Mrs. Wilson, has just finished his penetrations into the inner bastions of Soviet Russia to examine the Diderot library sold to Catherine the Great, now housed in a city once known to Tolstoy and others as St. Petersburg.

Lest such geography narrow the vista, in his preface Professor Wilson thanks 16 libraries (his greatest debts, he says, are to the Dartmouth College Library and to the Bibliothèque Nationale) and some 13 scholars (among them our own Charles R. Bagley and Francois Denoeu). Bibliographies run to another five pages of fine print.

This book, however, was written as much to satisfy the desires and curiosity of general readers as those of scholars. Hollywood would hardly dare film Diderot's life and loves. Difficult family problems leading to Freudian father fixation; Diderot (of all men!!) becoming an abbe; a clandestine marriage in Paris and clandestine children - the young wife parsimonious, tough-minded, and narrow, and the young husband reckless, enthusiastic, and cosmological; books so shocking that prison was thought the only place for so wicked an iconoclast and heretic; two mistresses (Madame de Puisieux and Sophie Volland) added to a wife, with rambunctious and name-calling jealousies; successful plays at the with attendant thrills about casting and production and charges that Diderot plagiarized from Goldoni And at the center of everything leading to emancipation and revolution is the Encyclopedic with its brilliant thinkers, loving and gesticulating, hating and hissing, Gallic style with Parisian overtones.

Diderot is the leading light, but about him flash the great names of the era. With delightful humor and erudition Professor Wilson comments on them: d'Alembert, Montesquieu, Buffon, Condillac, Voltaire and Frederick the Great, Grimm and Madame d'Epinay, Saint-Lambert and Madame d'Houdetot and Rousseau, Rousseau and Therfese Levasseur and Therise's mother, Helvétius and John Wilkes and Baron d'Holbach, at whose house every Sunday and Thursday sumptuous dinners with costly wines were served to 15 or 20 leading intellectuals, French and foreign.

Professor Wilson writes as if he had been present at every Baron d'Holbach dinner.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

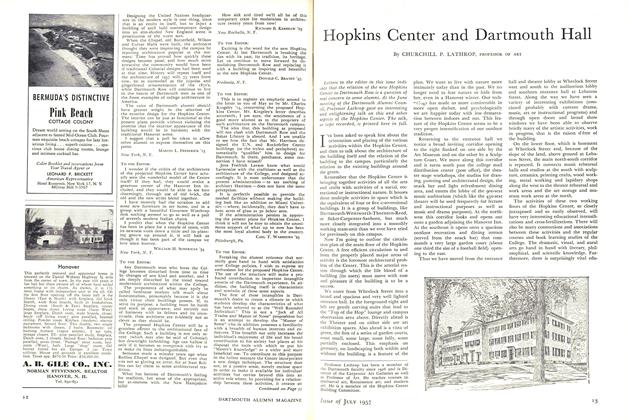

FeatureHopkins Center and Dartmouth Hall

July 1957 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

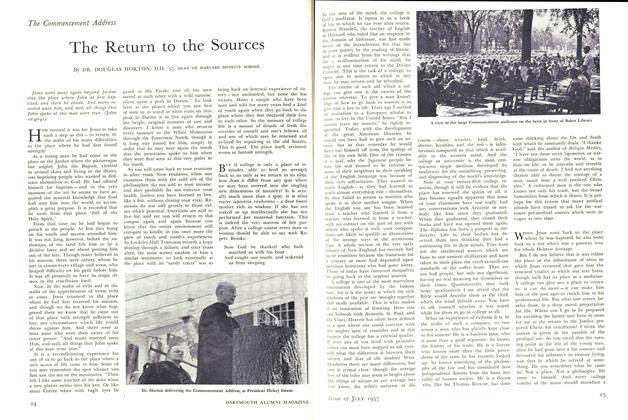

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1957 By DOUGLAS HORTON, D.D. '57 -

Feature

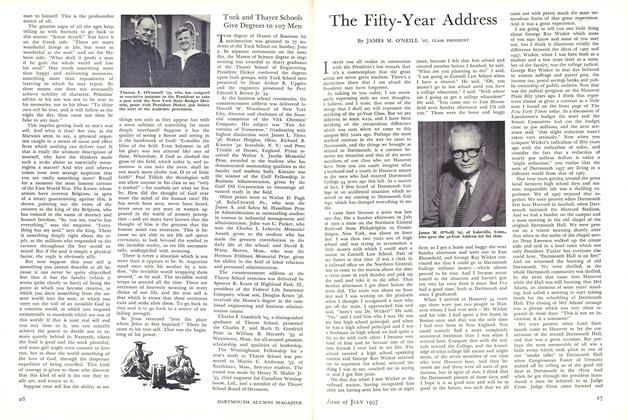

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1957 By JAMES M. O'NEILL '07 -

Feature

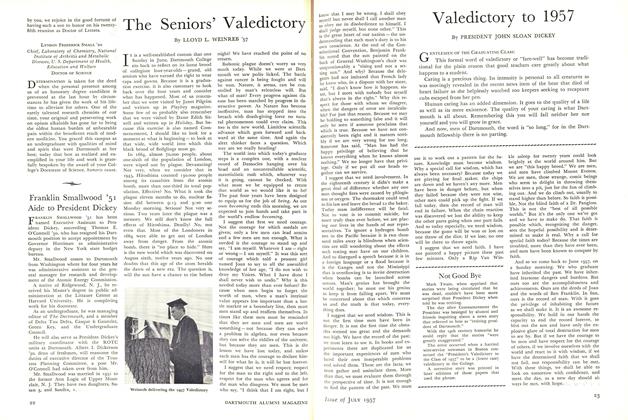

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1957 By LLOYD L. WEINREB '57 -

Feature

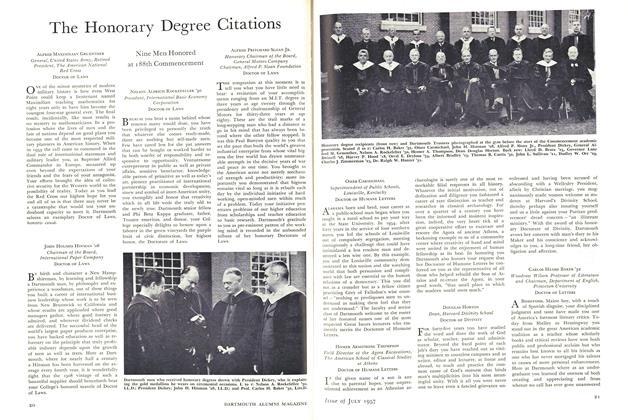

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

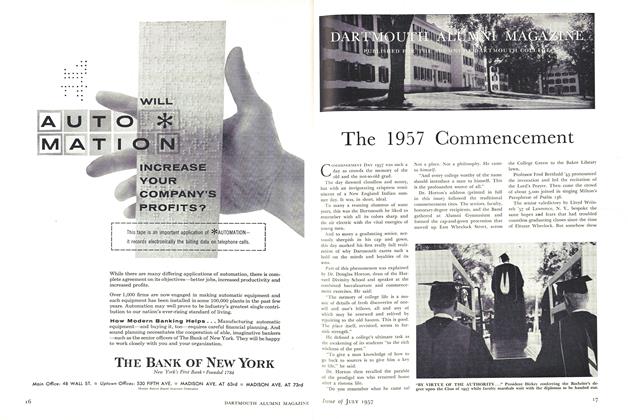

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksENGINEERING: ITS ROLE AND FUNCTION IN HUMAN SOCIETY.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSCENERY OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS.

MARCH 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleGREEN HIGHLANDERS AND PINK LADIES.

MARCH 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN INCLUDING PUERTO RICO AND THE VIRGIN ISLANDS.

JULY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOHIO AN ARCHITECTURAL PORTRAIT

October 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE VISIONARY UNIVERSE PROPHECY.

June 1974 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksSamuel W. McCall, Governor of Massachusetts

November, 1916 -

Books

BooksREBEL THOUGHT

June 1953 By Armstrong Sperry -

Books

Books"THE PRESTIGE VALUE OF PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT,"

FEBRUARY 1930 By Charles Leonard Stone -

Books

BooksFragmentary Future

JAN./FEB. 1979 By ELISE BOULDING -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January, 1923 By ERVIIXE B. WOODS. -

Books

BooksTHE STRUCTURES OF THE ELEMENTS.

December 1974 By ROGER H. SODERBERG