PRESIDENT OF SOCONY MOBIL OIL COMPANY

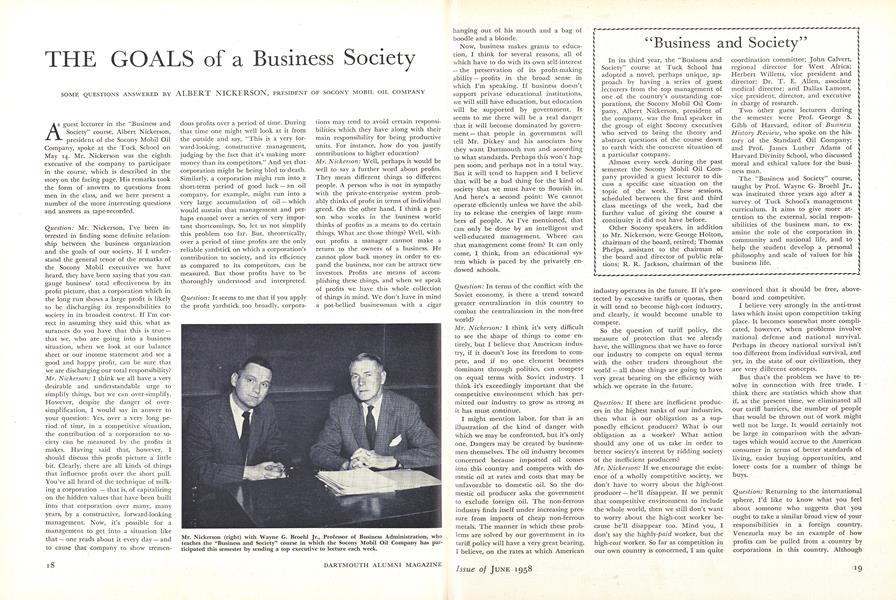

As guest lecturer in the "Business and Society" course, Albert Nickerson, president o£ the Socony Mobil Oil Company, spoke at the Tuck School on May 14. Mr. Nickerson was the eighth executive of the company to participate in the course, which is described in the story on the facing page. His remarks took the form of answers to questions from men in the class, and we here present a number of the more interesting questions and answers as tape-recorded.

Question: Mr. Nickerson, I've been interested in finding some definite relationship between the business organization and the goals of our society. If I understand the general tenor of the remarks of the Socony Mobil executives we have heard, they have been saying that you can gauge business' total effectiveness by its profit picture, that a corporation which in the long run shows a large profit is likely to be discharging its responsibilities to society in its broadest context. If I'm correct in assuming they said this, what assurances do you have that this is true - that we, who are going into a business situation, when we look at our balance sheet or our income statement and see a good and happy profit, can be sure that we are discharging our total responsibility? Mr. Nickerson: I think we all have a very desirable and understandable urge to simplify things, but we can over-simplify. However, despite the danger of over-simplification, I would say in answer to your question: Yes, over a very long period of time, in a competitive situation, the contribution of a corporation to society can be measured by the profits it makes. Having said that, however, I should discuss this profit picture a little bit. Clearly, there are all kinds of things that influence profit over the short pull. You've all heard of the technique of milking a corporation - that is, of capitalizing on the hidden values that have been built into that corporation over many, many years, by a constructive, forward-looking management. Now, it's possible for a management to get into a situation like that - one reads about it every day - and to cause that company to show tremendous profits over a period of time. During that time one might well look at it from the outside and say, "This is a very forward-looking, constructive management, judging by the fact that it's making more money than its competitors." And yet that corporation might be being bled to death. Similarly, a corporation might run into a short-term period of good luck — an oil company, for example, might run into a very large accumulation of oil - which would sustain that management and perhaps enamel over a series of very important shortcomings. So, let us not simplify this problem too far. But, theoretically, over a period of time profits are the only reliable yardstick on which a corporation's contribution to society, and its efficiency as compared to its competitors, can be measured. But those profits have to be thoroughly understood and interpreted.

Question: It seems to me that if you apply the profit yardstick too broadly, corporations may tend to avoid certain responsibilities which they have along with their main responsibility for being productive units. For instance, how do you justify contributions to higher education? Mr. Nickerson: Well, perhaps it would be well to say a further word about profits. They mean different things to different people. A person who is not in sympathy with the private-enterprise system probably thinks of profit in terms of individual greed. On the other hand, I think a person who works in the business world thinks of profits as a means to do certain things. What are those things? Well, without profits a manager cannot make a return to the owners of a business. He cannot plow back money in order to expand the business, nor can he attract new investors. Profits are means of accomplishing these things, and when we speak of profits we have this whole collection of things in mind. We don't have in mind a pot-bellied businessman with a cigar hanging out of his mouth and a bag of boodle and a blonde.

Now, business makes grants to education, I think for several reasons, all of which have to do with its own self-interest - the preservation of its profit-making ability - profits in the broad sense in which I'm speaking. If business doesn't support private educational institutions, we will still have education, but education will be supported by government. It seems to me there will be a real danger that it will become dominated by government - that people in government will tell Mr. Dickey and his associates how they want Dartmouth run and according to what standards. Perhaps this won't happen soon, and perhaps not in a total way. But it will tend to happen and I believe that will be a bad thing for the kind of society that we must have to flourish in. And here's a second point: We cannot operate efficiently unless we have the ability to release the energies of large numbers of people. As I've mentioned, that can only be done by an intelligent and well-educated management. Where can that management come from? It can only come, I think, from an educational system which is paced by the privately endowed schools.

Question: In terms of the conflict with the Soviet economy, is there a trend toward greater centralization in this country to combat the centralization in the non-free world?

Mr. Nickerson: I think it's very difficult to see the shape of things to come entirely, but I believe that American industry, if it doesn't lose its freedom to compete, and if no one element becomes dominant through politics, can compete on equal terms with Soviet industry. I think it's exceedingly important that the competitive environment which has permitted our industry to grow as strong as it has must continue.

I might mention labor, for that is an illustration of the kind of danger with which we may be confronted, but it's only one. Dangers may be created by businessmen themselves. The oil industry becomes concerned because imported oil comes into this country and competes with domestic oil at rates and costs that may be unfavorable to domestic oil. So the domestic oil producer asks the government to exclude foreign oil. The non-ferrous industry finds itself under increasing pressure from imports of cheap non-ferrous metals. The manner in which these problems are solved by our government in its tariff policy will have a very great bearing, I believe, on the rates at which American industry operates in the future. If it's protected by excessive tariffs or quotas, then it will tend to become high-cost industry, and clearly, it would become unable to compete.

So the question of tariff policy, the measure of protection that we already have, the willingness that we have to force our industry to compete on equal terms with the other traders throughout the world - all those things are going to have very great bearing on the efficiency with which we operate in the future.

Question: If there are inefficient producers in the highest ranks of our industries, then what is our obligation as a supposedly efficient producer? What is our obligation as a worker? What action should any one of us take in order to better society's interest by ridding society of the inefficient producers? Mr. Nickerson: If we encourage the existence of a wholly competitive society, we don't have to worry about the high-cost producer - he'll disappear. If we permit that competitive environment to include the whole world, then we still don't want to worry about the high-cost worker because he'll disappear too. Mind you, I don't say the highly-paid worker, but the high-cost worker. So far as competition in our own country is concerned, I am quite convinced that it should be free, aboveboard and competitive.

I believe very strongly in the anti-trust laws which insist upon competition taking place. It becomes somewhat more complicated, however, when problems involve national defense and national survival. Perhaps in theory national survival isn't too different from individual survival, and yet, in the state of our civilization, they are very different concepts.

But that's the problem we have to resolve in connection with free trade. I think there are statistics which show that if, at the present time, we eliminated all our tariff barriers, the number of people that would be thrown out of work might well not be large. It would certainly not be large in comparison with the advantages which would accrue to the American consumer in terms of better standards of living, easier buying opportunities, and lower costs for a number of things he buys.

Question: Returning to the international sphere, I'd like to know what you feel about someone who suggests that you ought to take a similar broad view of your responsibilities in a foreign country. Venezuela may be an example of how profits can be pulled from a country by corporations in this country. Although the standard of living of the Venezuelans is immediately increased, ultimately they know that the profits are being taken back to the United States. Is there any solution to this? Can a company continue these international relations without being at cross-purposes to the foreign policy of our country?

Mr. Nickerson: All right, let's think in terms of the oil industry's operations in Venezuela. Bear in mind, now, that a natural resource used to be locked in the earth. Nobody was aware of the fact that it was there. It was of no value. Now, that resource has been located; it has been exploited; it has been brought to market. It's important to realize there that in order to capitalize on it you not only have to find it but you have to make it available; you have to convert it into products, and you have to carry it to the consumer.

But, in respect to Venezuela, bear in mind that the relationship which exists between the oil company and the country itself is that the total profits of the enterprise, in Venezuela, are divided 50-50 with the Venezuelan government, which happens to be the landowner in that case. And that's only part of the benefits which accrue to Venezuela. The other part results from the fact that the oil company is a very large and a very enlightened employer of local labor. Oil companies have participated greatly in terms of the development of the region and in terms of the construction of roads, and houses, and hospitals, and schools. So I feel that a clear understanding of exactly what has happened in Venezuela in relation to the oil companies' participation in the growth of that country reveals that these benefits, which have been very great indeed, have devolved on both parties approximately equally.

Now, in relation to the money that is taken out of Venezuela, that isn't all bad for Venezuelans either, because it encourages a relationship between other industries in the United States and Venezuela. Following the experience of the oil companies, we have the illustration of the U. S. Steel Company which could observe the oil companies' experience. U. S. Steel has made a colossal investment in the iron-ore reserves in Venezuela. Well, there are lots of iron-ore reserves in other countries and the fact that the oil companies had a good experience in Venezuela, I think, encouraged other companies, not only from the United States, but from other countries in the world, to make investments in Venezuela, with concomitant advantages to both sides.

Question: Can a country such as Venezuela realize its own natural potential for higher civilization and for a maximum standard of living of the natives, if the dominant enterprises continue to be U. S. Steel and U. S. oil companies? Mr. Nickerson: Well, I think I have discussed the concept that the benefits of foreign enterprise in Venezuela have been great and have been shared substantially. Now let's look a little further. The oil companies have found, as have the steel companies, that the most undesirable thing from everybody's point of view would be for them to participate in the politics of the country. I dare say there were some experiences in the early days of the developments when they did participate. But they found that it was something which just paid reverse dividends very substantially. So there is a genuine understanding on the part of all our operations, and so far as we know, all other American companies of a substantial nature, that the politics of the local country is something that they must keep their hands clearly off.

Secondly, there was necessarily in the early years a large element of paternalism in these developments. Some years ago, the company built the houses for its employees. They weren't, perhaps, the kind of houses that the people wanted. They were much better houses, of course, than the people had ever lived in, but they weren't used to them, and they didn't have too much to say about them. Employees had to buy their food in company-operated stores. Their children went to company-operated schools. Well, as time has gone on and the standard of living has increased, a standard of education has developed which is significant. The oil companies now tend to back away from that kind of development. In respect to housing, they set up arrangements whereby the employee can set aside a part of his funds in a kind of savings plan; he can borrow funds: he can have his choice of a host of building plans; he can buy all his building materials at cost; he con- structs his own house. As time goes on, he participates more in the management of these projects and American expatriates become greatly reduced in numbers. He serves as a doctor in his own hospital, and he teaches in his own schools.

If you compared pictures of Venezuela in 1910, in the go's, and in the 50's, I think you would realize that this dominance, this impression of a foreign personality on a local country, which perhaps was necessary in the beginning, has tended to change very drastically. The company towns have disappeared except in the very remote areas where there is no alternative. The Venezuelans are running their own enterprises.

Question: Take a small foreign country in which you are a principal capitalist. What is your broad obligation to ensure security for your profits over, say, the next twenty years because you have heard that this country will probably fall to the communists?

Mr. Nickerson: Are you asking to what extent we are willing to fight Communism? It wasn't too clear to me just what you were driving at. We operate private enterprises; we are entrepreneurs; we take risks; we take calculated risks. We don't take risks where we don't think that the rewards are in keeping with the chances that we take. We will go into - in fact, we are in - countries that are all around the communist perimeter and are threatened to greater or lesser degrees by infiltration of one kind or another. We operate in most of them - for instance, most of the countries in South and Southeast Asia, such as Indonesia, which is currently in such a state of doubt and uncertainty. We have just completed an $80 million investment program in Indonesia over the last five years. Actually, we own half of the company, so that's $40 million. We are doing this all the time. But we never do it without resorting to a very careful analysis and evaluation of the risk and the rewards. We may lose everything, as we frequently do. We have an investment program in the Netherlands New Guinea, where we have, in joint operation with two other companies, invested over $75 million. We're drilling one last well, and if that well is a nonproducer as we expect, we are going to walk away from the whole thing. Now that was a geological risk which we took over a period of 15 or 20 years, and which has completely failed to pay off. It was in a country in which there was a considerable measure of political risk. What I want to illustrate is that risk-taking is greater in some industries than in others, and that it's particularly spectacular in the oil industry. The penalties for guessing wrong - and in many cases all investment is a guess - can be very severe.

The rewards can be equally tempting when these arrangements pay off. But this is a characteristic of the total free enterprise system. Every businessman, small or large, takes a risk almost every month, or week, perhap every day that he operates. People must be willing to take risks and this is why they must have the rewards available to them that are commensurate with the risks they take. And this is the particular danger in our society posed by the graduated income tax. If we should ever get to the point - I don't say that our income tax system has gotten to that point yet, but it's probably very close to it - when people don't take risks because they can't get rewards commensurate with them, then our free enterprise loses some of its vitality.

If it loses much of its vitality, then those people who are critical of the enterprise system will have more grist for their mill. They'll have more reason to say, "Well, private enterprise won't do it; the government must do it." The govern- ment takes over more and more and further and further and this question of regimentation and conformity, which bothers you as it does me, becomes a greater and greater menace. This, to me, is the danger of our modern society.

Question: Should a corporation justify its responsibility to the public - to society at large - on the selfish grounds that it can attain some personal gain. Or should it justify its responsibility on the grounds that it returns to society something that it took from society. In other words, isn't a corporation paying for the privilege that it has of operating within the society? Mr. Nickerson: I agree with that. But you see the picture that I am trying to project - and perhaps little by little it's coming out - is that in my judgment the free enterprise system and a free society are not separate things. They are wholly integrated with each other, and one cannot really exist without the other. If something should happen to our society which resulted in the restriction of the freedom of business initiative, then - I think unavoidably - individual freedom as we know it would end. I think all of us in this country are dedicated to the preservation of our free society. I think those of us in business can do most to preserve that society by fighting for freedom of private initiative.

ANOTHER Socony Mobil guest speaker in the "Business and Society" course was Dr. Theodore E. Allen, associate medical director of the company, whose topic was "Job Pressures and the Executive." The following excerpt provided the basis for a widely printed newspaper story:

Looking through the Dartmouth College Bulletin, I notice that the objective of The Amos Tuck School of Business Administration is to "prepare men to assume, after the requisite years of practical experience, responsible supervisory, managerial or administrative positions . . . (and) to improve the capacity of future executives. . .

That is a laudable purpose. But if students of the school read and accept the ideas contained in the bulk of current literature on the subject of job pressures and executive health, it would seem that they are also preparing for a working life in which the hazards to heart, stomach and psyche are approximately the same as those faced by the soldier in combat. The numerous books, magazine articles, and speeches on the subject almost universally offer a future in which you will (1) "suffer a crack-up" (2) "get promoted and then enjoy your coronary" (3) "accept a position advancement and develop a neurosis" (4) "reach the top and never enjoy an hour of relaxation again" or (5) "become a vice president and develop an excellent case of discontent" - and so on, without enjoying a single week's good health.

According to these disease-happy authors, you can look forward to no prospect which pleases you. You cannot hope to find happiness, job contentment, and good health. On the contrary, these authors insist, the day you become an executive, you abdicate your right to pursue happiness, and undertake an assignment which bodes only misfortune - physical, mental, and marital.

If the above quotations contained even a small measure of truth, my aim in addressing you would be clear. In all good conscience, I would urge you to run, not walk, to the nearest exit, and find jobs as experimental jet pilots, professional movie stunt men, or positions in some other such tranquil fields.

However, I am able to state without fear of contradiction that the medical profession in general - and particularly men in industrial medicine - do not in any way subscribe to the ideas on executive health currently being circulated for popular consumption. In reviewing the literature, I was immediately impressed with the fact that most, if not all, of these treatises were written by non-medical people. They make good, even amusing, reading, and no doubt they sell by the thousands of copies. But they are far from accurate.

There is no conclusive evidence to show that executives of Socony Mobil or any other company are any less healthy than day laborers, clerks or any other employees in comparable age groups. Indeed, we have every reason to believe that executives thrive on their responsibilities, and derive tremendous psychological satisfaction - fun, that is - from their work. A recent survey conducted by Industrial Relations Counselors, Inc., reports: "While it is known that the stresses and strains to which an executive is subjected can affect his physical health, statistics compiled by the National Office of Vital Statistics show that persons in the usual management category have a lower than average mortality."

Most physicians feel that the same statement can also be made in terms of sickness. Executives can cope better with these health problems than others who may have different yet equivalent stress from other sources. No clear-cut evidence exists which suggests that the working environment of management or executive personnel has any unique hazards.

Only recently have physicians closely associated with industry begun to discount the "scare" stories on executive health. No published medical data can or does substantiate the conclusions of the nonmedical press. Like other people, executives are susceptible to disease. But they should not be singled out as "museums of pathology" simply because they are or have become executives. Disease processes or entities do not inquire into the business status of a patient before they begin to impress their signs and symptoms on him. The exact time when degenerative processes begin varies with individuals, but physicians have observed that from a practical viewpoint the years between 40 and 45 seem to be the most likely age period. These processes, unless interrupted by the sound medical and health procedures currently available, will continue at an accelerated rate until death. This is just as true for a laborer as it is for an executive. No disease entity can be termed an "executive" disease.

It is the considered judgment of my department that the whole problem of executive health should be handed back to the medical profession, where it properly belongs.

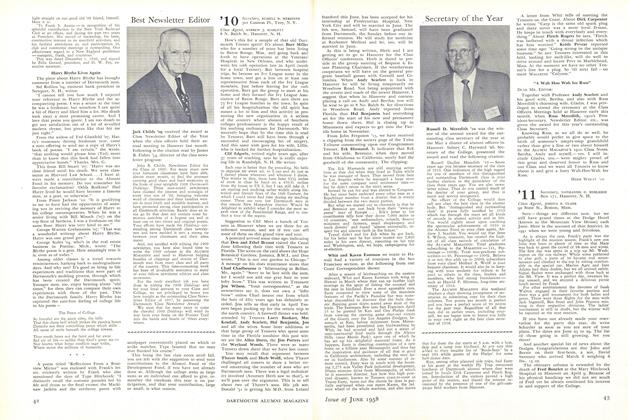

Mr. Nickerson (right) with Wayne G. Broehl Jr., Professor of Business Administration, who teaches the "Business and Society" course in which the Socony Mobil Oil Company has participated this semester by sending a top executive to lecture each week.

Mr. Nickerson answers more questions at TuckSchool after the formal class session ends.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

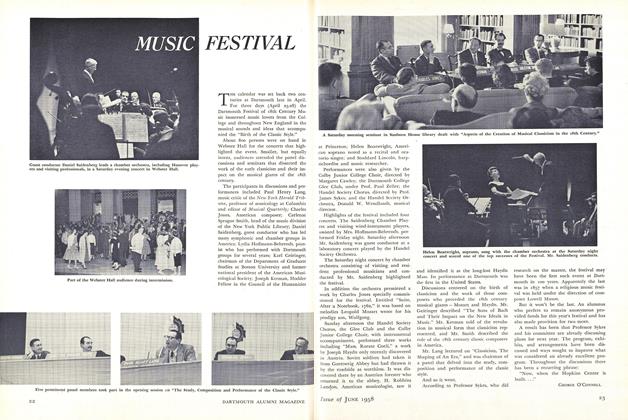

FeatureMUSIC FESTIVAL

June 1958 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

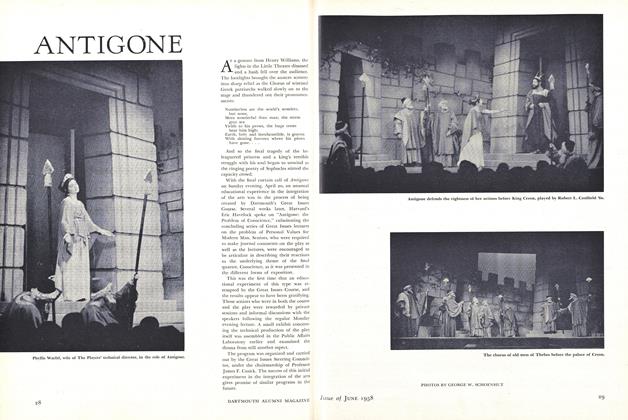

FeatureANTIGONE

June 1958 -

Feature

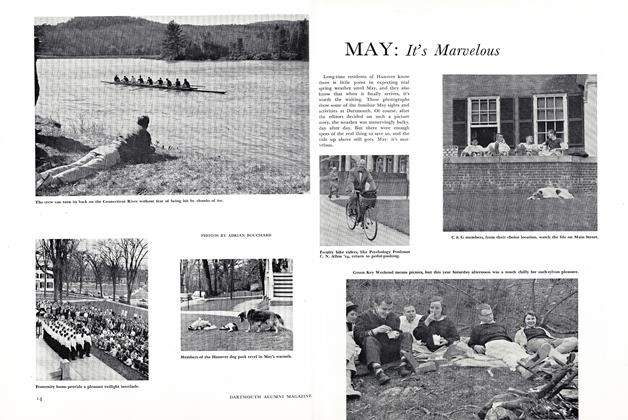

FeatureMAY: It's Marvelous

June 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910

June 1958 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, ANDREW J. SCARLETT, HERB WOLFF '10 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

June 1958 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

FEBRUARY 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDiseased With Poetry

MARCH 1995 By Everett Wood '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureRisky Business

Mar/Apr 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni College Retrospective

MAY 1983 By Jean Dalury -

FEATURE

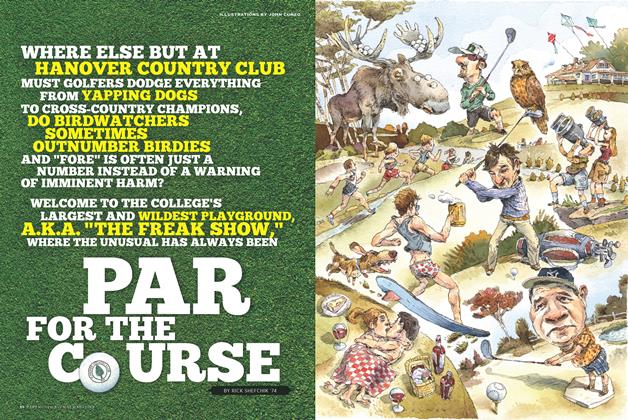

FEATUREPar for the Course

July | August 2014 By RICK SHEFCHIK ’74