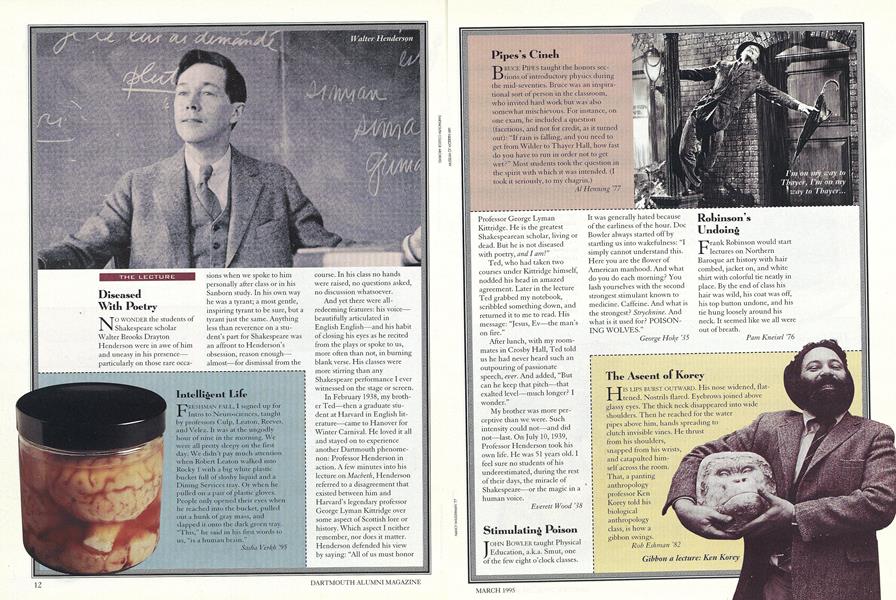

NO WONDER the students of Shakespeare scholar Walter Brooks Drayton Henderson were in awe of him and uneasy in his presence-particularly on those rare occasions when we spoke to him personally after class or in his Sanborn study. In his own way he was a tyrant; a most gentle, inspiring tyrant to be sure, but a tyrant just the same. Anything less than reverence on a student's part for Shakespeare was an affront to Henderson's obsession, reason enough— almost—for dismissal from the course. In his class no hands were raised, no questions asked, no discussion whatsoever.

And yet there were allredeeming features: his voice-beautifully articulated in English English—and his habit of closing his eyes as he recited from the plays or spoke to us, more often than not, in burning blank verse. His classes were more stirring than any Shakespeare performance I ever witnessed on the stage or screen.

In February 1938, my brother Ted—then a graduate student at Harvard in English literature came to Hanover for Winter Carnival. He loved it all and stayed on to experience another Dartmouth phenomenon: Professor Henderson in action. A few minutes into his lecture.on Macbeth, Henderson referred to a disagreement that existed between him and Harvard's legendary professor George Lyman Kittridge over some aspect of Scottish lore or history. Which aspect I neither remember, nor does it matter. Henderson defended his view by saying: "All of us must honor Professor George Lyman Kittridge. He is the greatest Shakespearean scholar, living or dead. But he is not diseased with poetry, and I am!"

Ted, who had taken two courses under Kittridge himself, nodded his head in amazed agreement. Later in the lecture Ted grabbed my notebook, scribbled something down, and returned it to me to read. His message: "Jesus, Ev—the man's on fire."

After lunch, with my roommates in Crosby Hall, Ted told us he had never heard such an outpouring of passionate speech, ever. And added,' But can he keep that pitch—that exalted level—much longer? I wonder."

My brother was more perceptive than we were. Such intensity could not—and did not—last. On July 10, 1939, Professor Henderson took his own life. He was 51 years old. I feel sure no students of his underestimated, during the rest of their days, the miracle of Shakespeare—or the magic in a human voice.

Walter Henderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryGetting Things Right

March 1995 By Donald Goss '53 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Tasting

March 1995 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

March 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryQuite Good

March 1995 By Abner Oakes IV '81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPoesis

March 1995 By David Bradley '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRousseau Cops an Exam

March 1995 By Philippa M. Guthrie '82

Everett Wood '38

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI TRY THEIR WINGS

January 1941 By Everett Wood '38 -

Books

BooksDistant Drum

December 1980 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Parkhurst Elm

OCTOBER 1998 By Everett Wood '38