President Dickey's Convocation AddressOpening Dartmouth's 190th Academic Year

IT is not yet a year since man hung his first exhibit in the heavens. Just a few days ago perhaps man's most ancient figure of speech passed into the oblivion of reality; "aiming at the moon" is no longer an opprobrium to be borne by visionaries. Scientists are now paid down-to-earth money to do just that as their daily work.

Lest we mistake these wondrous things for the sudden coming of a very adult world, there is still the nightmare of this past summer when the child of all our hopes, peace, once again teetered and tottered between the perils of summit and brink - both of them poor places for raising children.

And yet somehow here we are once again gathered together as a community of learning much as this community for nearly two centuries now has gathered annually under the aegis of Dartmouth.

Two years ago on this occasion I spoke of Dartmouth as a place, of the lessons of independence that are uniquely built into this adventurous place and are now here at hand for each man's learning. Last year our discussion moved across the threshold of institutional and individual independence into the limitless domain of creativity wherein alone man's lot becomes personal to each man and human experience is enlarged idea by idea.

Today as we face forward into one of the newer years of this College's history I want to speak with you about that marriage of place and men that we call a community. There are many kinds of communities and all of us are born into the first ones we know - family, home town, religion and nation. These first communities come into our lives, so to speak, ready-made. They come readymade for us not because they came in the same package with the hills but rather because men and women out ahead of us created and re-created them out of their individual lives.

A community is the product of purposeful men and women. Any community lives only as each day its life-giving atmosphere of common cause is created and replenished out of the personal purposes of its members. No community rises higher than the quality of common cause in its atmosphere.

Common cause is a synthetic in the literal sense because it is a put-together and built-up compound created by the union of its elements. It is a difficult synthesis to achieve in any human situation and yet it is indispensable to the working of democracy.

I sometimes wonder whether we all do not minimize or even at times dangerously disregard the difficulties that must be met in making the common cause out of which a community o£ learning is created and re-created. There is even a form of romanticism that goes to the extreme of picturing academic communities as immune to all the tribulations, trifling and otherwise, that arise wherever two or more human creatures are gathered together - for long.

In truth a community of learning such as ours has all the problems of any other community plus those that are peculiar to the educational purposes and processes that bring us together.

BORROWING the terminology of medicine, we can surely say that a healthy college community is remarkable in both its anatomy and its physiology. Its indispensable part, the student body, is made up of several thousand individuals each of whom is in transformation as he begins to cross life's last great divide from dependence to independence, from immaturity to the outposts of maturity, from the ravenous animal appetites of youth to the restraints and cultivated tastes of civilized man, from a self-centered boy to a public-minded man; and with it all, hopefully, he is learning to think and like it.

As a body this sector of our community is given perilously little time to learn and grow from experience. It is never the same body for more than one academic year at the end of which its most experienced portion is dispersed and the body is reconstituted with freshmen who soon will be sophomores.

The other great body of our community, the faculty, of which all the rest of us are a part or a dependency, is perhaps an even less promising prospect for producing stable and predictable syntheses of common cause. Our nature and our business is otherwise. In our search for a truth which is personal it is our destiny to be a centrifugally oriented group of individuals. As teachers we each day face the challenging paradox that he alone teaches truly who in the same moment is himself learning. This, I take it, is the essence of creative teaching, perhaps the highest mission of creative thought simply because in whatever form such teaching occurs it, and it alone, transmits man's most precious heritage, the will to think.

A man thinks only as he thinks for himself. Thinking for yourself is like self-education, there is no other kind. Thinking can serve common causes but common causes cannot think. The primary aim in all higher education is enlargement of the life of the mind and to that end as to all ends we occasionally jeopardize other things, including the serenity supposed to go with having everyone "think" the same way. This does not automatically entitle our thinking to an "A" simply because it is different from everyone else's, but it does mean that a community of learning unlike most other communities makes independent thought itself a common cause. In such a community other causes are often harder won just because of that.

And yet, however far the encouragement to independence may go here or elsewhere, it always ultimately comes up against the problem of coming to terms with standards that limit independence and thereby define the very existence of a community. In an important sense a college is set apart and given independent existence simply because it enforces standards as to admission, good standing and, above all, the witness of its degree that what was required was performed. Other places, notably our major cities, have libraries, lectures, museums, playing fields, social life, even tutors for hire - all the visible ingredients of a college except one: institutional standards.

Whenever you and I, and I often do, find it hard to understand why one "measly" C—, or perhaps a glorious binge or two, should stand between a man and a Dartmouth degree, the timeless answer comes that a college without standards is soon no college at all. The stake of each of us in this community is grounded in the standards we honor.

The standards of a college community are nevertheless one of its most hard-won common causes. It is not merely the unhappy burden of enforcement that must fall to someone, be it teacher, dean or student committee. More basically this problem in common cause is one of fixing responsibility for judgments that touch the very existence of the community. The issues range from educational program to the personal bearing of each of us at his post of duty. In the need of both wisdom and answerability these issues are great with difficulty.

THE dimension of wisdom in any issue is rarely measured in general terms and we cannot probe that community need from this platform today; it must suffice here to record our awareness of its need in every community as well as in every life.

The problem of responsibility or, perhaps better, of answerability is critical in every community. The closer a community approaches pure democracy the more difficult is the problem of answerability simply because it too often becomes less and less clear in such a community who is answerable to whom for what. A community where no one is answerable is by definition an irresponsible one and an irresponsible community, like one without standards, is soon no community at all. Here is one of the ancient dilemmas of democracy.

American life at all points, as in most free societies, is becoming more democratic in that more people at least seem to have more say as to more things. As a general direction for a free and mature society this seems to me both inevitable and right. I am also sure, however, that this development has within it the seed of its own undoing unless it is accompanied by corresponding growth in the same community's resourcefulness in reconciling independence, answerability and the dilemmas of leadership within the democratic process.

The community of learning lives on the frontier of these problems. On the one hand such a community stakes its all on the forward thrust of the free mind, build our community around this

common cause even though on occasion it produces something akin to the France of Jean Cocteau's boast where "no one takes anyone else's word for anything." On the other hand, it is axiomatic that a community privileged to live on the frontiers of freedom is always up against a Janus-faced enemy; his scowl is tyranny; his smile, irresponsibility.

Variations of answerability in both form and substance are especially great in a community of learning. Here at Dartmouth under our venerable Charter - tested by twenty more years than the Nation's Constitution - twelve trustees are solely answerable for all that can be laid at Dartmouth's door at least in the eyes of the law. The rest of us are variously answerable with our heads or our reputations, depending upon the tenets of academic freedom and tenure for the teacher, the nature of our shortcomings and the sensitivity of our consciences. In between the outer boundaries of the irrepressible and the responsible three thousand students and some three hundred teachers and staff do the daily work of this community of learning and, I say to you, do it immensely well. And so it will be just so long as each of us is answerable in one form or another for nothing less than himself. This is the minimum standard of answerability in any community; it is not, and in a healthy community never can be, the maximum. Maximum responsibility is the companion of leadership.

The dilemmas of leadership within the democratic process are deep-rooted. Its absence is deplored and its conspicuous presence is as often resented except in those dire moments when we'd all just as soon be off-stage. And yet leadership by stealth can itself rob the democratic process of answerability. Students of the subject rightly tell us that leadership is importantly a function of response on the part of all of us and that in a democratic situation each of us plays a more personal role than we often realize in evoking the leadership we want and get. Leadership like virtue is better practiced than claimed, and little more can appropriately be done on this occasion than not to ignore the subject. In so far as it is the problem of the fellow on my job, and it is of course inevitably so, he can only promise to seek his part of the answer in the doing of each day through his personal identification with each element - colleagues, students, alumni, benefactors and trustees, all of whose purposes go into the common cause that binds Dartmouth together as a community of learning.

PARADOXICAL as it may be that a community of learning is built on the common cause of independent thought and baffling as the internal conflicts and contradictions of such a community often are both to its members and to outsiders, the great truth remains that these communities with all their built-in troubles and imperfections are the best hope our world has that it may itself someday be a community.

Today's world is one in many things, but it is assuredly still short of a community with enough sense of common cause in law to keep the peace. On a world basis we have barely begun the work of creating the understanding and building thereon the political institutions within which the enduring tension between independence and union can be creatively reconciled for nations as the nations at their best have done for individuals.

I cannot help but feel that recent years have been a terrifyingly sterile period on the front of achieving a minimum measure of international community. I think I understand the good reasons for this condition as well as the next fellow, but this does not make me less concerned that our preoccupation with the troubles of the day may short-change the morrow. The far-sighted proposals of the American government for the international control of national activities in outer space are a notable and reassuring exception. Let us make the most of these proposals both for their own purposes and as a possible detour route for getting back to earth with a creative instead of fearful perspective on the count-down into tomorrow.

Communities of learning the world over should be our best bet for pioneering such creative routes into tomorrow. If we leave this kind of forward work primarily to governments we shall at best, as the Pennsylvania Dutchman put it, be "backing up ahead" all the way. Our colleges and universities need a sense of forward mission; they cannot for long be true to themselves simply by "running scared."

We can all share the satisfaction of knowing that the new educational programs we move into here at Dartmouth today reflect the conviction of our fine faculty as to how this College can be most responsive to its opportunities; they are not a mere reflex response to someone else's challenge. As with any new effort we shall meet unexpected as well as foreseen difficulties in our new program, but even in such difficulties you who are here today as students will have the supreme educational experience of learning with rather than from fine teachers.

The love of truth and beauty and the willingness to search endlessly for better answers in man's relationship to both man and his Maker are the over-arching common cause that first brought teacher and student together here and now daily re-create the union of our community of learning. A community with such a soul enlarges a creative man; a community by whatever name without such a soul cannot but diminish him.

If this be the faith of this community, if you and I believe these things, we will be as one regardless of all else while still remaining free to be many in all else.

And now as we go forward into this pioneering Dartmouth year, welcoming the Class of 1962 into the fellowship of Dartmouth and each of its men into this community of learning as one of us, let us all remind each other:

Each of us is a citizen of this community and is expected to act as such; we are the stuff of an institution and what we are it will be; our business here is learning and that is up to each of us.

We'll be with each other all the way and good luck to us.

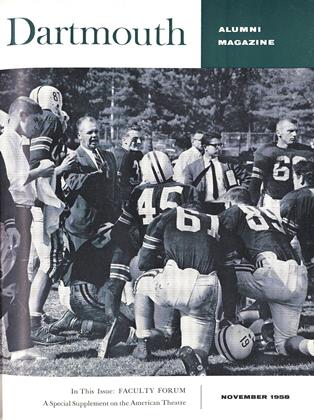

President Dickey delivering his address in the west wing of Alumni Gymnasium.

Another September address by President Dickey took place at the dedication of the ChoateRoad dormitories during the opening week of college. Mr. Dickey, seated right, listens tothe remarks being made by John F. Meek '33, Vice President and Treasurer of the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

November 1958 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

November 1958 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

November 1958 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

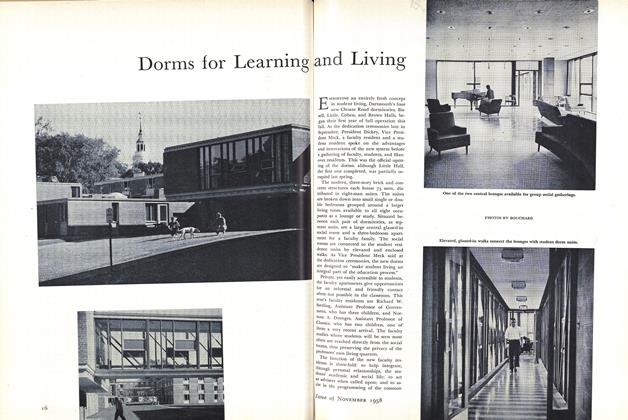

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

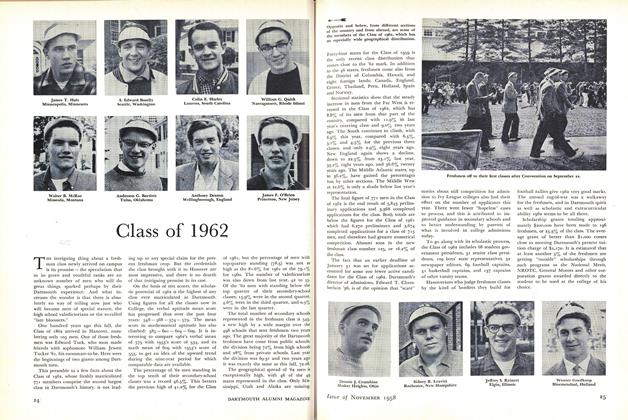

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958 -

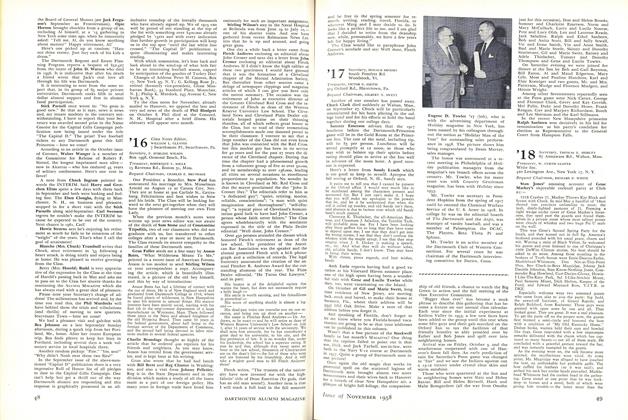

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1958 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ...

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Features

Features“His Life Was a Gift”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Cover Story

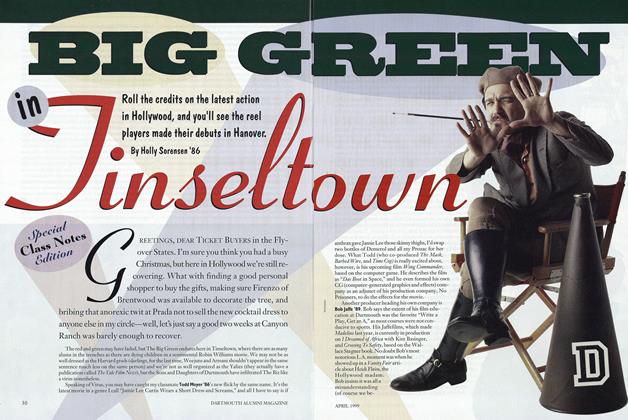

Cover StoryBig Green in Tinseltown

APRIL 1999 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ...

December 1987 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

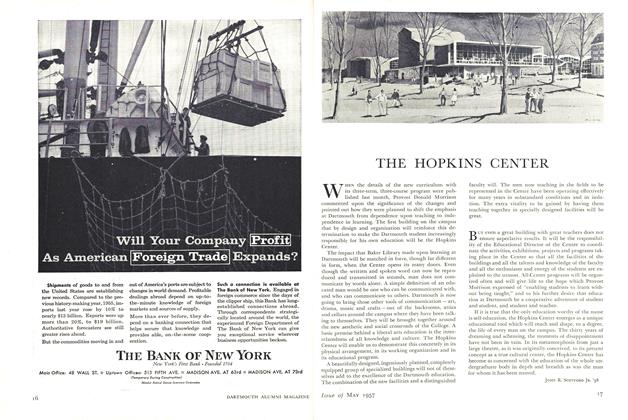

FeatureTHE HOPKINS CENTER

MAY 1957 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Feature

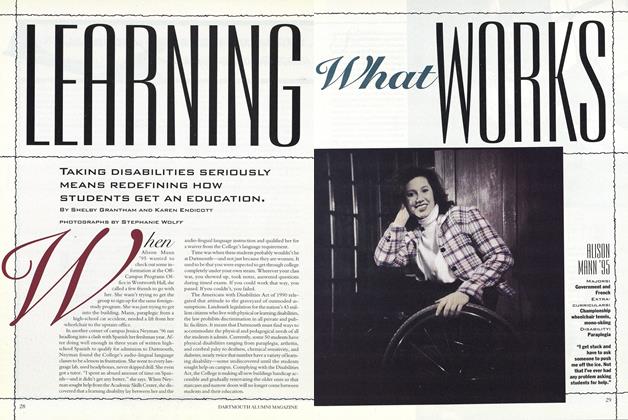

FeatureLEARNING WHAT WORKS

May 1995 By Shelby Grantham and Karen Endicott