A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE

Number I • November 1958

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

FOR a long time no one has seen a Fairy Godmother; vainly one rubs lamps and strokes the necks of bottles - no genie appears. Yet we keep on making wishes. And oddly, the wishes sometimes come true. I am making wishes for America - but only for what some would call a tiny, insignificant part of America, its theatre. Yet what could one wish for America greater than that its art should serve to make its life enjoyable? And what art so directly moves to make life enjoyable as the theatre does, and what art has been so clearly chosen by Americans for making life enjoyable as the theatre - with its offshoots, movies and television? So to wish for the American theatre may not be insignificant. Anyway - Five Wishes.

I wish the theatre would decentralize.

Who would have supposed, before World War II, that grand opera of high calibre would be easier to find in American cities outside New York than legitimate theatre of high calibre? But that is true today. In legit there is only one city; all the others are parasites on it. But the San Francisco Opera is not parasitic on the Metropolitan; a young singer with opera ambitions doesn't have to go to Europe and wait for a chance at New York any more. But a young actor has to go to New York; it's getting harder and harder to get into Hollywood without New York experience. Why should the young actor be so restricted? Why can't Detroit develop actors as well as automobiles? There are plays enough. There are actors enough. If there aren't theatres enough, we can make them. Why haven't we good theatres in every city of 20,000 or more, as Germany has? Let New York remain the theatrical capital, if it can maintain that position, but let it have some competition. If it ever gets that competition, it will be good for the New York theatre as well as for the competitor. When the Little Theatre movement began in the second decade of this century, it seemed that New York's grip on the theatre might be broken. But the Little Theatres seem to have mostly become unwilling to venture. They will do only Broadway plays in the Broadway manner. They use actors from the community, get many other services from the community, and in return give the community the New York successes of two or three years ago. This is disheartening, because the theatre in any society must make its audiences see visions and dream dreams, must startle it with unexpected vistas and unanticipated revelations. It must be fresh, somehow, somewhere. And the theatre which presents only warmedover Broadway does not really fulfill its function.

The academic theatre does fulfill its function - Dartmouth's is a prime instance. I think the American academic theatre is one of the hopes of the world theatre. It has already powerfully affected the world theatre — in the spread of arena staging, for instance. It is helping to make playwrights, scene designers, directors for the world theatre, for legitimate, TV, movies. In some parts of the country the academic theatre is the only theatre, and in many the best theatre available. But even the academic theatre is tempted by its community to limit itself to the easy imitation of Broadway; that is what undergraduates are apt to like. The academic theatre is also bound by its nature to the young and inexperienced, to the amateur, to haste and improvisation. Yet out of the academic theatre may come the rival Broadway needs. In Seattle, I understand, the University's theatres, which number three, completely overshadow the commercial theatres. Why doesn't Harvard try to take the same lead in Boston? Boston needs it.

I wish there were more theatre gamblers.

Nothing can be done, short of totalitarian socialism, to make show business secure. If you're in it, you're a gambler. I don't want totalitarian socialism, and I do want show business, so I must want gamblers. But the gamblers I plead for here are not those who gamble with their lives, like actors, or scene designers, or directors, but those who gamble with their money, like producers, or theatre owners, or just plain fastbuck chasers. These are all, I take it, at least a little reconciled in advance to losing their money if they have to. In New York, enough such people seem findable; they are known as angels, and they have lately begun to organize themselves into corporations, and to take the precautions corporations take against being wiped out. They spread the risks; they diversify; they research. Whatever they do, and however unangelic their activities, they can't beat the statistics: about two-thirds of all the shows produced lose money.

But the backer of a show, it seems to me, must have rewards other gamblers don't have: the reward of backing his artistic taste and judgment, the reward of employing interesting people in an interesting activity. Do those same rewards come to poker-players or horse-players? There must be a small fraction of the horse- or poker-players who would take a chance on a show, and only a small fraction would be needed at first. And they must be findable outside New York. Couldn't a Detroit poker-player let it be known that he was ready to read new or foreign plays with the aim of backing one or two for production in Detroit? Instead of buying shoes for his brother poker-players' babies, he'd buy them for actors', scene designers', and directors'. And he just might win. He might find a Journey's End, which came about almost in this way. And how many millions did Journey's End make?

Besides the big gamblers, the American theatre needs the penny-ante ones, the men and women who will support the theatre in advance of production with their subscriptions. The Theatre Guild in New York has always been a subscription theatre; though it has lost its other differences from other commercial producers, continuing subscription financing has given the Guild a stability the theatre generally lacks. The great community theatres of the country: Cleveland, Pasadena, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, are all of course subscription theatres. The subscriber to a theatre is not so committed that he cannot find fault with the management, but he is committed enough so that he should prefer finding that he got his money's worth to finding that he didn't. But I wish the subscriber were more often persuaded to participate by appeal to his gambling. Now he is told that he will save money. "For $25 you can have ten tickets, or $2.50 a seat. The public will have to pay $3.50. You save $10." That's a good argument, but the man who contemplates five shows a season with his wife should also be persuaded to gamble $25 more, or $50 in all, for which he will get ten tickets to the regular list — probably old Broadway hits - and a blanket ticket to the theatre's experiments. Then if any of the experiments proves successful enough to get into the regular list, he gets a pro rata share of the public's contribution to the play's run. It wouldn't be much, ever, but it would be something. The theatre could use its gamblers' income on classic and foreign and new plays. What that would do for the American theatre and eventually the American public is incalculable.

I wish we were not so respectful of critics.

In the history of any art - music, painting, literature, the theatre - the critics have been wrong as often as they have been right, and when they have been right the people at large have made them right, not their own talent or insight. Yet the critics go on exercising their steely authority. Everyone knows they can kill a Broadway play, or even an off-Broadway play; they can make or ruin careers. Part of their power, of course, derives from the unfortunate economic position of the theatre. High costs mean high box-office prices; theatre-goers can't afford to run the risk of being bored when they have to pay so much. Therefore they take Walter Kerr's word for it - he says it's a good play, and they won't buy anything Walter doesn't recommend. But part of the critics' power also derives from the artistic timidity of audiences. I think that timidity increases, oddly enough, with education. The untutored playgoer will proclaim his opinion without fearing whether it is orthodox; the educated one distrusts simple reactions, wants to complicate them, is not sure precisely how, except that he must not innocently enjoy or dislike as a child does. Here the critic helps him. He can agree or disagree, but he starts with the critic rather than with himself and the work.

Though I am sure this is regrettable, I don't know what can be done about it. I guess we need less criticism of the theatre than we get. I am sure that the theatre would gain if it were not regarded as news, having to be judged at first performances and reported upon as soon as possible. I am sure there is a lot of enjoyment available to audiences if they never read a word of criticism but just go to the theatre like children and try to have fun. So far as we can tell, that is the way Shakespeare's groundlings went to the theatre - and look what they got. We need in theatre audiences, I think, less mind and more enthusiasm.

I wish we had more classic actors.

Here the English theatre will help me show what I mean. Asked "Who are important English actors?" anyone would say, "Olivier," "Gielgud," "Edith Evans," "Ashcroft," "Red. grave," and so on, and every one of them would be important for what he or she had done in Shakespeare or other classic plays. But that is not the way American actors get distinction. American actors get distinction apparently by long runs, by being in something so popular that they have to do it over and over again for years and years. Then when they are distinguished enough they can limit their runs and, though they let the world know they can go on for years and years in the same part, they won't. Then they have reached the top. I wish actors tried for short runs in memorable parts. The actors who get most space in American stage history: Edwin Booth, Ada Rehan, Sothern and Marlowe, played in classic plays. Miss Cornell now can be depended upon to seek the classic play or the potentially classic, but who else is there?

No doubt the explanation lies not so much in the wishes of the actors as in the American attitude toward the stage. Americans do not now regard the theatre as a place where they may be enlightened and enriched in mind and spirit. They want simply to be entertained, to forget business or domesticity in laughter or easy sympathy with the immediately recognizable. But I think Americans were ready to elect the Barrymores to the position of The Classic Actors, the Royal Family, whose leadership would take the American theatre to the heights, and then the Barrymores showed they lacked the taste and stability the position demanded. Canada seems to be working toward the establishment of that kind of aristocracy of actors with its Stratford troupe. Such an aristocracy gives morale to the whole profession and a desirable tone to public opinion of the stage. If we had such an aristocracy, Americans might demand more of the theatre and of themselves in the theatre. The American Shakespeare Theatre Academy, training young actors in performing The Bard, deserves praise for its work to this end, but I would hope it would also train in Greek tragedy, using some of the more colloquial modern translations, and in monumental plays such as Faust or Peer Gynt. To build a part in these plays must give satisfactions to the actor unparalleled otherwise. And the audience for such plays will surely grow.

Someone may object, "Actors don't decide what plays shall appear. The mony-people decide. An actor can say, 'I am a Shakespearean actor,' but he will say it to the wind unless the money-people want to put on Shakespeare." This is true, but it is also true that an actor can himself become one of the money-people. The actors in England do it; Olivier and Gielgud manage companies and put on plays of their own choice. The actor-manager system has been used in America - George M. Cohan was an actor-manager; husband-wife teams like Harrison Grey Fiske and Mrs. Fiske, Guthrie McClintic and Katharine Cornell, have been actor-director-manager. The system has its faults, but the American theatre needs more of it.

1 wish our playwrights had a differentpicture of the nature of Man.

The picture of the American, male or female, which nonAmericans might get from American plays no doubt represents accurately enough what the American is and thinks ought to be. I take it this American is efficient, honest, reasonably domestic, thoroughly material in his values, rather anti-intellectual, generous, so easy-going in his codes of behavior that he would rather forgive than punish, hard-work- ing, distrustful of all emotion, and even more distrustful of all ideals. Some playwrights add to this fundamental American character. Tennessee Williams, for instance, adds drives of various kinds: sex drives, especially in women; power drives in both women and men; greeds; lusts; fears. The picture that results is the shallow, kindly American character twisted violently into a human weapon, directed against other characters. Arthur Miller, on the other hand, convinced that character is only the product of environment, leaves his people somewhat mindless; they are incapable of self-examination; they are shallow and kindly but they come to bad ends because the environment lacks the kind of organization that would direct them to happiness. Mr. Miller knows that there never has been and never could be such an environment, and man's tragedy is therefore, as it were, built-in. But his view of man makes him powerless to perceive and correct the causes of his tragedy, though they lie outside him. Mr. Williams sees the causes of man's tragedy as internal, rooted in his nature, and man perceives them, but doesn't want to correct them. They are as precious to him as life itself.

These two will do to illustrate why I wish for a more searching view of the nature of man in our playwrights. Fashionable though determinism, will-lessness, behavior as conditioned reflex, and so forth are as academic theories, and even assuming - what I am sure is not true - that they are the only proved and provable theories of human life, nevertheless, they damage the drama. Drama without will is like marriage without romance; it can work, can even be good, but it's so much better the other way. Among the plays of the modern period I think none excels in popularity and lasting appeal Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac, not only because it is written with brilliance and is supremely an actor's play, but also because it flies the banner of the will. To make the shallow, kindly American into a Cyrano is perhaps difficult; maybe the American's environment or his internal drives make him a victim rather than a master; but even so, let us pretend in the theatre that we are bigger, bolder, more dominant.

And we might be shown in the theatre that we are not merely animals. Thornton Wilder is the only living American dramatist I can think of now who shows a belief that man has a spirit transcending flesh. In the history of drama what great writers have ever viewed man as merely a creature of this world? Shakespeare did not; Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides did not; Goethe, Racine, Molière did not. Bernard Shaw thought the mass of men pretty poor stuff, but the heroes and saints showed what we could be, and would be if we obeyed the Life Force. Eugene O'Neill tried mightily to see into the relations of God and Man, he told us, and he seems to have ended in the bleak nihilism of The Iceman Cometh. But even nihilism is better than the still bleaker evasion of finding any meaning in the great issues of birth and death, beauty and ugliness, sin and virtue. Why do American dramatists say so little with this kind of meaning? Probably as a group living American dramatists are the second best in the world; only the French, with Anouilh, Beckett, de Montherlant, Ionesco, Sartre, and others, excel us, but they excel us because on the whole they have a wider and deeper vision into the nature of man, though certainly they are not cheerful about it. But in their view to understand man is not easy; he always carries about a mystery; at the edges he is dark, however bright for good or evil his center.

I fear our playwrights have adopted the easy confidence of the head-shrinkers, at least in their public pose, that they know all the answers. But the artists should never be scientists, should, I think, fear science. Art is long while science is short, because art is tentative while science is sure. Art has a history it treasures while science has a history it is ashamed of. Let our playwrights dream dreams, explore mysteries, get lost in the darkest recesses of the human soul. And the Man they will show us after their journey will be more impressive and - surprisingly - more convincing than any shown by science.

But my wishes are really for America. The land is full of talent, rich with energy, lovely in intelligence. America deserves arts as great as her destiny.

THE AUTHORS of these three articles on the American Theatre have all been students and devotees of the stage for many years. For biographical notes about them, see Page 3 of our November carrying this special supplement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

November 1958 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

November 1958 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureA Community of Learning

November 1958 -

Feature

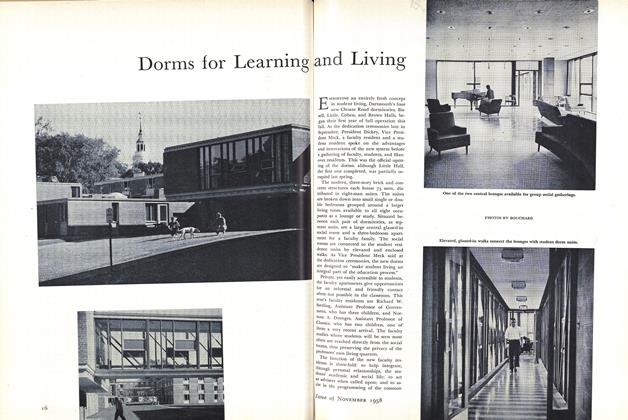

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

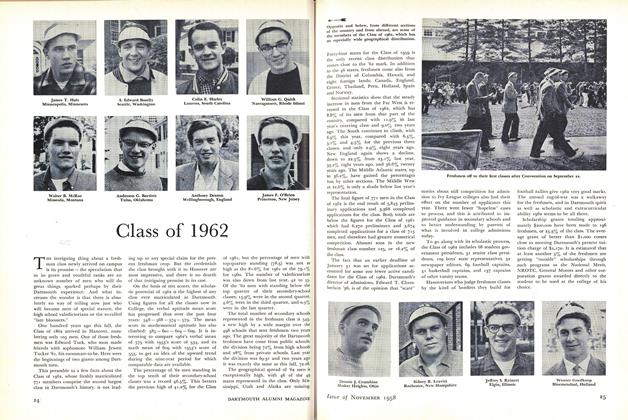

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1958 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ...

BENFIELD PRESSEY

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1981 -

Article

ArticleHollywood at Work

November 1938 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Article

ArticleMusic In the Center

February 1940 By Benfield Pressey -

Article

ArticleDavid Lambuth (1879-1948)

October 1948 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksTHE TITAN: VICTOR HUGO.

October 1955 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksSTUDIES IN THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE DRAMA.

MAY 1959 By BENFIELD PRESSEY

Features

-

Feature

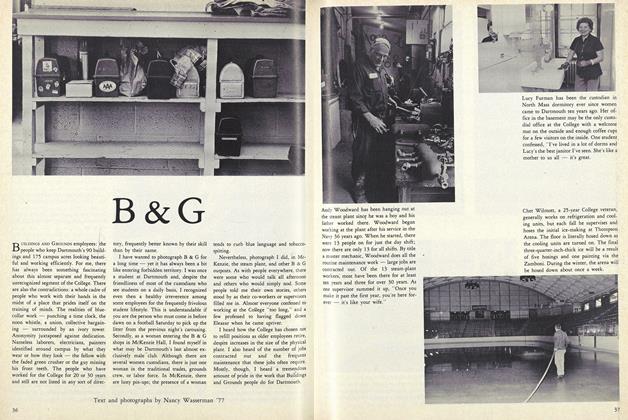

FeatureB & G

NOVEMBER 1981 -

Cover Story

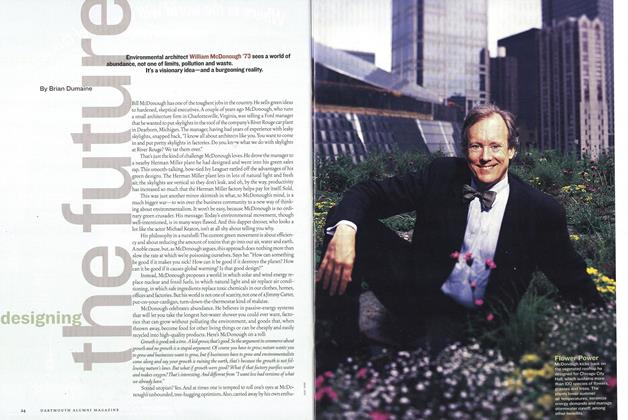

Cover StoryDesigning the Future

Sept/Oct 2002 By Brian Dumaine -

Feature

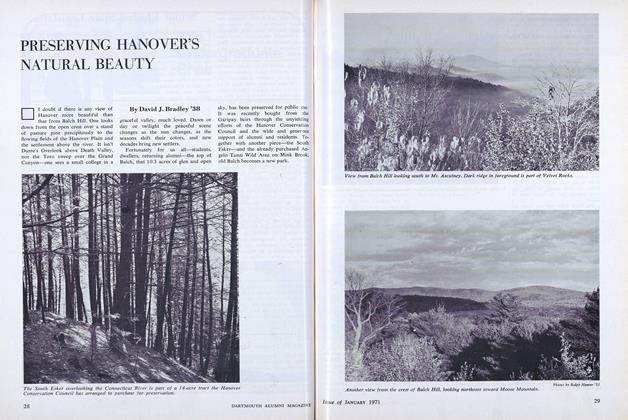

FeaturePRESERVING HANOVER'S NATURAL BEAUTY

JANUARY 1971 By David J. Bradley '38 -

Feature

FeatureRisky Business

Mar/Apr 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

APRIL 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureReport of Twenty-Sixth Alumni Fund

April 1941 By SUMNER B. EMERSON '17