5, DIRECTOR OF THE EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

THE American theatre is, of all our arts, the least permanent and most perishable. This characterizes not only the performance of a play and its disappearance after a long or brief run, but almost every phase of theatre activity. Once a play is finished nothing remains to recall it except some soiled programs trodden under the feet of the departing audience, the cold playscript which may or may not have been published, and the bare walls of an empty theatre. The actors disperse, never again to be recalled. The play, at least in one form, is completely dead and has vanished. The empty theatre has become a byword in our language signifying ghostliness.

There is a sentimental romance which weaves itself around all this, and it would be charming, except for the cold fact that a good part of this romance is the result of terrific waste and unorganized chaos. The professional theatre in this country has never been able to make up its mind whether it is a business or an art or both at once. If it is purely business, it is a horrible example of bad economy. If it is an art, it seldom rises to the high level of aspiration that any self-respecting art should attain. If it is both, it is a poor fusion of the two.

By its very nature the theatre is a cooperative art. The playwright is the beginning. His script is the springboard, the genesis of the whole process. Unlike a novel, or any other kind of literary work, his script is not the end but the beginning. His conceptions of scenes, characters and plot are filtered through the minds of the director and actors and are eventually seen only as related to the experiences of the whole theatre group. Even his description of a setting, so clear in his own mind, usually suffers a sea-change in relation to the physical limits of the stage, the mind and experience of the director, and the imagination of the scene designer. It is obvious, then, that if cooperation is not the keystone of the theatre arch, the whole process falls completely.

Granted cooperation is necessary, our theatre does everything it possibly can to make cooperation difficult. We furnish bare theatres into which the producer for each play must bring every single thing necessary to the production of a play. Even those devices common to all productions have been eliminated from the theatre and must be supplied by the incoming production. The very actors in each play have probably never acted together before and have been assembled because they conformed to desired "types." And they may never play together again after this production has closed. All the personnel of the production have their own private offices and separate business set-ups. To bring all these together to make a cooperative enterprise work is a major effort. The playwright may have two or three scripts in production and each of these may be in the hands of a different producer. The scene designer of one production may easily have three or four other shows to design for three or four different managements. The scene builders are probably building five or six other shows at the same time. Only the director and the actors, for the moment, give their single and wholehearted attention to the particular script in hand.

This is business with a capital "B," yet its very set-up and organization defy the attainment of any sort of "teamwork" so beloved by business and industry. If the theatre were business pure and simple, there would be a wholesale reorganization of its scattered parts into a cohesive unit. The trouble, however, is that the theatre is also art and it is the respect of business for art that permits this wasteful chaos. If business would let art alone perhaps art could find its own way out. But business won't let art alone, especially theatre art because there is too much money to be made in it. There is almost no investment that returns so much in the way of dividends as a "hit." And the "hit" has become an end in itself. It is rarely part of a process of growth toward the art of the theatre. The "hit" then becomes a dead-end road and not a milestone pointing toward an even greater goal beyond.

In its chaotic and diffused pattern of organization the theatre is unable to set up those safeguards of supply that are the life-blood of any art. At the moment it would seem to be senseless to do so. The supply is unlimited. Several thousand new playscripts are copyrighted yearly and all of these descend on New York City. A fair proportion of them are read by playbrokers and managers and a scant few ever get as far as the stage. In the same manner, actors in the thousands descend on New York and only a minor percentage ever get behind the door of a casting director's office. In every art the biblical verse "Many are called but few are chosen" represents the sad truth. But in this art form can we be sure that we have a good system for choosing the right ones? Of the plays endlessly written in the United States only a handful, to be sure, are worth a second glance. But is the handful that gets the second glance the right handful? Of the thousands of aspiring actors only a very few, we know, have greatness in them. But can we be sure, with our impermanent and wasteful organization, that the ones who do succeed in our theatre are really our very best? Isn't there always a lurking, gnawing feeling that perhaps somehow the one who might have been the greatest of all time has been discouraged and has been forced to find an outlet for his talent elsewhere? The theatre is a chancey thing at best and our system seems to have a built-in method for ignoring every means whereby we may save and foster our better talents.

Not too long ago, certainly within living memory, the situation in the American theatre was entirely different. In those days, of course, the theatre was not as socially or financially acceptable as it is now, and in general the theatre belonged almost exclusively to a group of people known as actors and managers. They lived a life apart from the normal community primarily because their working hours differed considerably from those outside the profession. The Victorian world retired early and late social hours were frowned upon except on rare occasions. Thrown back upon themselves, most of the theatre people practically lived within a theatre building and thus were forced to devote all their spare time to their profession. Even at the expense of seeming to exaggerate, it is pleasant to record that in those "good old days" there were many, many theatres, all of which had resident companies." In remote places throughout the breadth of this expanding country travelling troupes played to the delight of the theatre-starved population.

This is no dream or fable of a once glorious past. It really happened. In those days too aspiring young actors descended on the theatre, and by a wide dispersion of its activities that theatre was able to absorb almost all the proffered talent. An interested youngster could apply to the local troupe and if he seemed sufficiently persevering and talented was absorbed into the company. If he proved to be of exceptional ability he could hope to progress within the company. If he was very exceptional he could move on to a more important city, and beyond that he could hope to become an actor-manager and move about the country as a visiting star.

In those fabled days the theatre building itself was a treasure-house. Each theatre had from fifteen to twenty different sets of scenery which normally would cover all the usually required locales, whether it be a cathedral portal for The Two Orphans or a scenic view of the Ohio River complete with ice floes for Eliza to cross chased by bloodhounds in Uncle Tom's Cabin, or Life Among The Lowly. For lighting, each theatre had its own gas table for dimming or raising the level of illumination and no one ever thought of carrying any extra equipment.

This was an actor's theatre. The actor walked in and the theatre enveloped him with its panoply and he acted. No one in the audience cared whether the setting used to represent the Ohio River in Uncle Tom's Cabin served also for the river and prospect in the first scene of Engaged. The settings and costumes were merely to lend verisimilitude of a kind and, except in rare extravaganzas, no one minded if the setting wasn't utterly accurate.

The old theatre, then, was one where an aspiring actor could go and learn his trade. He met with a permanent resident company, many of whom had been with the theatre for years, and he received "on-the-job" training. Almost everything he needed was enclosed within the walls of the theatre building. A resident scene-painter painted the settings. A resident seamstress made and repaired the costumes. A property man kept all the props in shape and built new ones as they were needed. Even the advent of a touring star hardly altered the case. The star's manager came the preceding week and ran through a line rehearsal of the play, indicating in his own person where the star wished to stand at any given moment. The resident company knew that what was required of them was to keep out of the way or serve as conversational warm bodies in those scenes in which the star did not soliloquize. Even this did not alter the fact that each theatre reared its own coming generation, and in the main reared it well.

This venture into the past is not intended here to be anything more than factual. Nor is it well to pause over a past with misty eyes unless one can learn something from it. The spread of the late 19th century theatre throughout the length and breadth of the land gave employment to many more actors than we can today. And to people in other branches of the theatre, too, it was a good, hard school. With the advent of the motion picture the old Stock Company and the Repertory faded from the scene. Theatres all over the country were converted into cinemas as a practical use of valuable real estate. So far as the film people were concerned this merely cut down competition, but it is obvious now that with the demise of the Stock and the Repertory companies there was no longer a place to train actors. We are paying for this today.

In looking for a solution to the problems that beset the present-day theatre in the United States it might be well to turn to Europe and take a look at the Continental Theatre. The European theatre produces much the same type of play that our theatre does but has had to face the problem, which we have never really had, of working under a budget demanding great economy of production and personnel. In the main Europeans have solved this by making their theatres permanent and self-sustaining. The nurture and education of the European actor in his profession must command the profound respect of any thoughtful theatre-lover. Schools of the theatre, whether or not they are attached directly to a particular playhouse, are tied in very closely to the profession. The program of plays is varied and catholic and anyone who has the opportunity to go through this training emerges as a first-rate actor with a wide range of styles and parts at his command. As in the old American Repertory, such actors can look to advancement easily within their profession. This sort of arrangement makes sense and is economical as well.

On the other hand, the producer of an American play is virtually unhampered. He does not have to search for an experienced actor or even necessarily one with advanced training. He has this vast reservoir of talent flowing into New York every year and he can cast to type. In fact, the New York theatre frowns on casting anyone who might not be the exact counterpart of the role he is asked to play. Most American actors end up by playing themselves over and over again. And most American actors pride themselves that they hardly ever use any make-up when they act.

The United States too has schools of drama where everything practiced in the theatre is taught more than competently. But these schools, many of them located in our great colleges and universities, have little or no connection with the professional theatre. Yet these are the only places where one can go if he wants sincerely to make the theatre his profession and learn his job in a systematic way. The professional theatre needs such schools but it cannot cooperate with them even if it would. Because of its impermanence it cannot cooperate even with itself. Instead, it tries to compete within itself. Each production hopes to be a bigger hit than any other production, as though the theatre were merely offering a single product to be put out by competing businesses. This puts the theatre, which basically is an art, on the level of, say, the automobile industry where each production is competing against last year's model and against a rival company's similar product. But plays aren't this sort of thing at all. An audience doesn't select just one play as its sole choice, but generally can find enjoyment and merit in many of the plays of a season.

In Europe, the majority of city and state theatres foster their audiences in all sorts of ways. They form the habit of theatre-going early by school matinees and also by the production of such a varied program of plays that every taste is supplied with its favorite fare. The theatre does this easily because it works under a permanent structure and organization. Our hit-or-miss system is working seemingly to discourage audiences from attendance. The European theatre tries hard never to "type" an actor, with the result that the actor is challenged by the variety of roles he is asked to play and seldom gets stale. We ask an actor to play a part and if the play becomes a hit he plays that role endlessly until the hit has run its course.

Possibly the most important contribution of the European theatre is the repertory of plays it serves its patrons. Along with the most modern plays from every country the continental theatre has a great stock-in-trade in the classics and these are carefully and lovingly produced. Actors benefit from the freedom and style that classical acting demands and the audiences are able to see these stage masterpieces in superb productions. The result is an educated theatre audience, sophisticated beyond anything that we in the United States can imagine. This can be done only by the setting up of a permanent organization for production. Compared with this, our theatre seems, and indeed is, fly-by-night. Every time we produce a play we have to start at the beginning and work on it from the ground up. In Europe they produce each play within a well-defined structure of experience and organization which eliminates more than half the back-breaking preparation.

At this point the reader might well ask: "Is there anything good about our theatre?" The answer is a resounding "Yes!" Despite all that has been said, we have for the most part an extremely serviceable theatre. Far better than we deserve. We have all the elements to make our theatre the best, or as good as the best, in the world —in spite of the loose organization. Our good actors and directors persist in doing good work despite setbacks that would frighten away less fervent spirits. Much of what is done on Broadway is excellent and is so regarded by the rest of the world. But there is surely something wrong with the American theatre when an American play that is a resounding international success can be seen only in a few token cities in the United States but can be seen in the local theatre of any European town or hamlet large enough to maintain a playhouse. One can only assume that those responsible for the American theatre have failed miserably in about three-quarters of their job.

What is the answer? Any straight answer has a terrifying look and any real solution will be uphill, back-breaking work. We have all the elements needed to make our theatre work, but we will have to restore habits of theatre-going to a people who, through long neglect, have forgotten how. We must play fair with our audiences wherever they may be. The road production must be as good as the original in New York and Chicago. For actor training it might be well to establish farms as the baseball teams do and farm out our actors before they hit the big leagues. Cities and towns throughout the country should get their citizens to take the lead and set up a local theatre with a permanent stock or repertory company under sincere and professional leadership. This is the European way, and earlier this was the American way, all through the 19th century. This was, in effect, our heritage which we sold for a mess of pottage.

But most of all, the theatre in New York should look closely at itself, to see where its great strength lies and then nurture it. It must broaden its repertory to include plays that are worth doing and not only those that look like surefire hits. It must become both responsible and reputable to the whole nation. It must, in short, build into itself a degree of permanence which will permit its devotees to find shelter and its audiences deep enjoyment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

November 1958 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

November 1958 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureA Community of Learning

November 1958 -

Feature

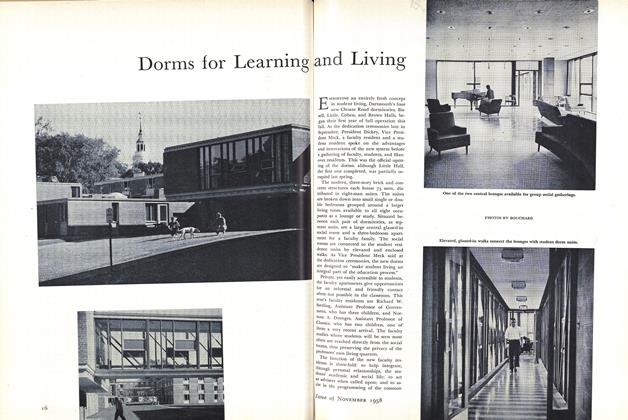

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

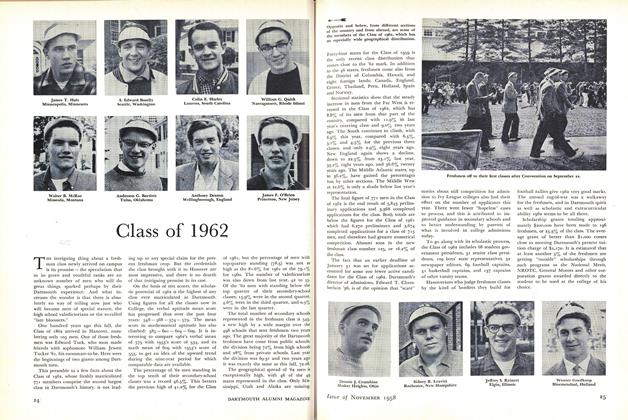

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1958 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ...

PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS

Features

-

Feature

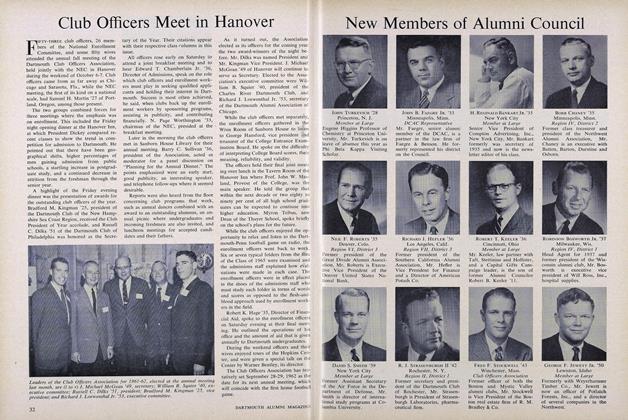

FeatureClub Officers Meet in Hanover

November 1961 -

Feature

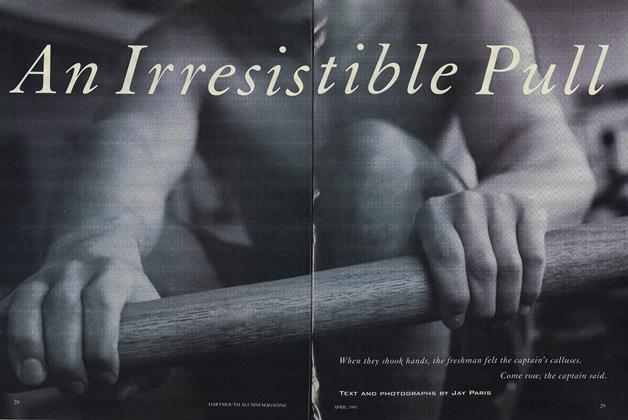

FeatureAn Irresistible Pull

April 1995 By Jay Paris -

Feature

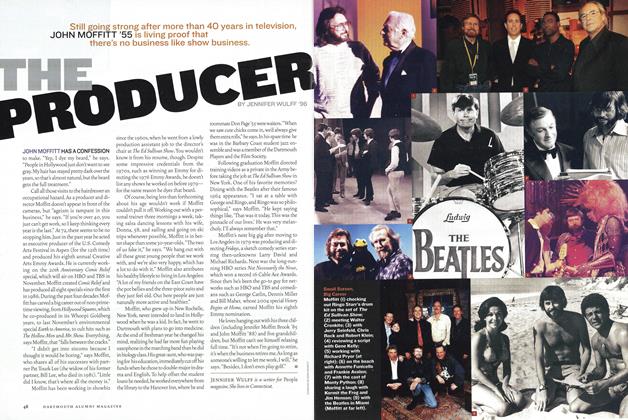

FeatureThe Producer

May/June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Cover Story

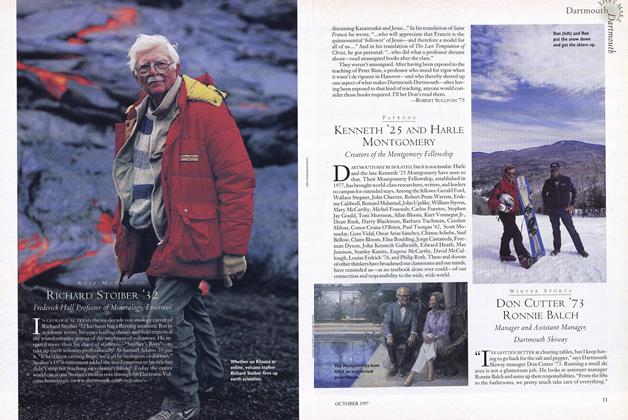

Cover StoryDon Cutter '73 Ronnie Balch

OCTOBER 1997 By Mark Schiffman '90 -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx