DEW LINE: DISTANT EARLY WARNING, THE MIRACLE OF AMERICA'S FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE.

March 1958 EVELYN STEFANSSONDEW LINE: DISTANT EARLY WARNING, THE MIRACLE OF AMERICA'S FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE. EVELYN STEFANSSON March 1958

By Richard Morenus'17. New York: Rand McNally, 1957. 184pp.$3.95.

Geography has decreed that the presently powerful nations of the world form a wreath round the shores of the Polar Mediterranean Sea. With the development of longrange planes, the "short-way-is-north" gospel preached 30-odd years ago by one V. Stefansson has become a commonplace. Half a dozen commercial air routes criss-cross the top of the world and SAS passengers flying thrice weekly from Copenhagen to Tokyo scarcely bother to look up (or down) from their luxurious breakfasts as they cross the exact North Pole, the spot Peary labored for 30 years to reach.

The frightening truth that we were no longer separated from our most powerful competitor by two oceans and a continent, but by less than half a dozen flying hours to the North, finally penetrated Defense Department headquarters. (Their tardy realization may in part be explained by the curious circumstance that before World War II there was no regular course in geography at West Point!)

In 1952 at M.I.T.'s Lincoln Laboratory, spurred by a contract from the U. S. Air Force, some of our finest scientific minds were asked how best we could defend our country from atomic attack by high-speed bomber. Among the many factors considered, the most vital and immediate seemed to be that of early warning. This was the beginning of "Project 572," known to us as the DEW Line, the Distant Early Warning radar screen which now stretches across the base of the North American continent from Baffin Island to the Aleutians.

Into this virtually uninhabited land, where sea ice conditions permitted only a short latesummer navigation season, where the number of roads could easily be counted on one hand, where permafrost and muskeg spelled tragedy for the inexperienced, came the builders of the DEW Line. Sites must be selected, the few men with arctic training must educate enough Cheechakos to build and man the stations. The formidable logistics and imagination involved in shipping to the sites not only needed materials, machinery, spare parts and food but every piece of string and bit of paper that might possibly be needed, is staggering. And it had to be done on a timing schedule that would permit maximum construction during frost-free seasons.

Overland by long cat-trains of sledges, northward by sea with ice-breakers smashing a trail, down North over frozen river highways, by barge over the same rivers after break-up, by airlift and by monster snowtired trucks, the largest arctic expedition in history converged on the DEW Line sites.

Classified as secret, it was only in 1955 that the first discreet notices appeared in the newspapers. From time to time a new morsel of fact would be doled out to readers, but the full story was scattered in many papers over a two year period, with key pieces of information lacking.

Now Richard Morenus '17, tells us, for the first time in book form, the stranger-than-fiction story. Morenus is no newcomer to the Northland. Among his many books are several with northern backgrounds. With excellent support from both the U. S. and Royal Canadian air forces and from the Western Electric Company, who built the Line, .he visited the stations, talked with the men engaged in the venture and gives us a hearty account of what he discovered.

Some argue that the DEW Line is already obsolete, others that it is still the keystone of our defense. No matter what side you find yourself on, the tale of its building is fascinating history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe State of Our Purposes ... and Vice Versa

March 1958 -

Feature

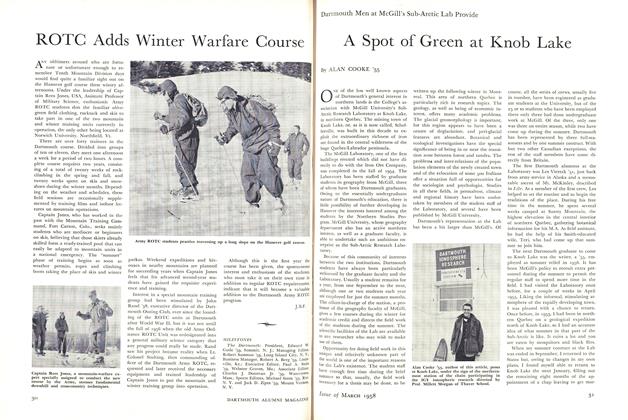

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Feature

FeatureA BIG NIGHT AT THE WALDORF

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Has Record Attendance

March 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1958 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Notes

March 1948 -

Books

BooksRed Man's Burden

March 1975 By BENEDICT E. HARDMAN '31 -

Books

BooksDOUBLE PLAY.

JUNE 1970 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

NOVEMBER 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksSELECTED POEMS.

MAY 1966 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

February 1921 By Wilbur M. Urban