In his annual report to his colleagues, the outgoing clean of faculty assesses the College's competitive strength and advantage.

ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS are located along a continuum that ranges from the small teaching college on the one hand to the large research university on the other. This spectrum is not hierarchical. Different objectives, characteristics, and strengths tend to mark these institutions. To say that a University of California at Berkeley is better than a Swarthmore College is to express a preference for a certain type of institution and certain types and scales of activities rather than any clear assessment of intrinsic institutional quality. Each of these places and others like them are among the finest colleges and universities in the world. They define themselves differently and are valued by society for different reasons and for different strengths.

This continuum of higher education is not a one-dimensional measuring device, but rather it frames a set of descriptive qualities that tend to differentiate rather than to rank. A ranking requires that we impose a qualitative vertical dimension on the continuum. There may be a number of institutions at any point, and among these there is a sharp differentiation in terms of quality. Not every college is a Swarthmore. And few research universities are Berkeleys.

Those places situated on the teaching college end of the continuum are characterized by certain qualities. These include:

• an emphasis on teaching as an activity • a total commitment to undergraduate education • a curriculum, at least among the liberal arts colleges, that is marked by breadth of coverage, based on the idea that the liberal arts have an obligation to introduce students to the range of human knowledge and activity • a sense of faculty egalitarianism: all colleagues share in the same tasks and the same types of assignments; merit and accomplishment are recognized, but they tend not to be marked by differential treatment and status • faculty at the teaching colleges are campus-focused in their orientation • budgets tend to be "hard money budgets," dependent on more or less secure sources of revenue such as endowment income, regular gifts, and, most importantly, tuition and fees.

The American research university as it has evolved since World War II tends to be characterized by a different structure and mission, a different scale, and a somewhat different set of values. These include:

• an emphasis on research as an activity • a strong, if not a dominant, commitment to graduate education • selective depth and concentration in staffing the strength of research universities and surely of graduate education requires having concentrations of people sharing interests and engaging in the same fundamental forms of inquiry • research universities are marked by faculty meritocracy: there is not a sense of equivalent contributions but a clear understanding that the research accomplishments of some faculty are far more significant than others and that these faculty should be recognized and rewarded accordingly • faculty at research universities tend to be professionally focused as opposed to campus focused, engaging with colleagues in their discipline and field literally around the world perhaps even more than they professionally interact with colleagues on their own campus • the research universities have a fundamental need to sustain their enterprise through grant and contract revenue: their staffing and other long-term arrangements depend upon—indeed re- quire—this form of continued "soft money" support.

IF WE TRY TO FIX Dartmouth's current niche on this continuum, we immediately confront some of the historical ambivalence of this institution. Our own Planning Steering Committee report several years ago noted that "Dartmouth strives to blend the best features of the undergraduate College with those of a research university.

The movement of Dartmouth over the last half century has been toward the research end of the academic continuum. Beginning with the administration of John Sloan Dickey and continuing today, we have recruited research faculty who are more professionally focused and involved, and we have become much more competitive in seeking outside support for our research.

We have changed in structure and have expanded our objectives, but, importantly, we have done this without serious compromises in the scale and the culture that emphasizes our teaching purposes. It is unambiguously the case that we have over this half century also moved up along the vertical or qualitative continuum. We are not only descriptively different, but we are qualitatively better as a research institution—and as a teaching institution.

In recent years there has been an ongoing discussion within this community about Dartmouth aggressively seeking to be even more competitive with American research universities. Certainly we do well, even very well, in many comparative rankings. We have been more successful in getting grant support. We are very competitive in recruiting faculty. And we are attracting the very best students in the country. Nonetheless, we still lag in some rankings, notably the National Research Council's assessment of grad uate education. Seeking aggressively to improve these would require a major new infusion of resources and may entail actions that have important consequences. These need be understood at the outset.

Let us consider some of the ways in which Dartmouth is structurally different from the very top research universities in the United States. We know, of course, that the great public universities are significantly larger, indeed are of a different scale from ours. Berkeley grants over 800 Ph.D.s a year, and we award fewer than 50. But in many ways the other great private universities are also larger. Comparing Dartmouth with a selected group of private institutions, including all of the Ivy League schools, MIT, Stanford, Cal Tech, Northwestern, Chicago, and Johns Hopkins provides an important calibration.

The National Research Council report stated that faculty size correlates directly with perceived quality in reputational rankings. Dartmouth has a significantly smaller arts and sciences faculty than any of these other private institutions we are 25 percent smaller than the average for the group. Even more importantly, the profile of our faculty differs. In 1995-96,42 percent of our faculty were fall professors, by far the lowest percentage m this group. The actual number of full professors is also the smallest, half that of the group average. We have the smallest faculty size in our Ph.D. departments, only slightly more than half the average number m our counterpart departments in this group. The number of graduate students in our graduate departments is less than one-third ot the average found in comparison departments at these other institutions. Relative to the company we keep, we are a remarkably small school.

We need to consider the implications of these differences. Since no one is suggesting that we grow to match the scale of the comparison group, we must continue to seek to identify ways to compete with American research universities, and to compete aggres- sively, but selectively and successfully. In order to do this, we would need to be more explicit in our goals, more understanding of our limits, and even more prudent and strategic in our decisions. We would need to think about the desirability of additional selective expansion of the faculty, an expansion that would build upon research strength and upon research potential and opportunity more than the traditional factors that have shaped these allocations.

Dartmouth has long been on a path—a trajectory of change and of ongoing competition with the very best universities in this country to recruit students, to recruit faculty, and to generate support and resources. I believe that we need to continue to do this, but we can't pretend to be of a scale that we are not. We can't lose sight of our competitive strength and advantage as a research institution committed to teaching.

President Freedman said several years ago that we aspire to be the very best of what we already are. I fully support this formulation: Our commitment is to improve quality without fundamentally altering the nature of the place. It is the case that in recent years many of the leading universities in this country have begun to emphasize some of the values that we have—be it Stanford's program to generate new courses and faculty for teaching in the introductory courses or effort to get current senior faculty more involved in undergraduate teaching. Harvard and Columbia have recently recommitted themselves to some important undergraduate teaching initiatives.

It is obvious that the tremendous and rapid growth of the postwar era is over. Many are now asking universities to account for their activities and to rethink their core mission and purpose. We need to be very careful about undertaking culture changes here that would attempt to compete with models that are themselves already subject to modification. Dartmouth is gifted with a student body that is among the handful of the very, very best in this country. Our students are academically strong, they are committed, and they are eager to learn. And students like this did not come here simply by accident. For despite all of the other things that may make this an attractive institution for young people, it is the quality of the learning experience, the quality of the classroom and laboratory, the studio and library, the quality of the faculty, that will tell.

It is my hope that we will affirm and emphasize again that we have at this place research faculty who are involved in the work that is helping to define their fields and disciplines, and research faculty who are truly committed to strong and effective undergraduate teaching.

Historian JAMES WRIGHT became acting provost of Dartmouth thispast January. His term as dean of faculty expires in June.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

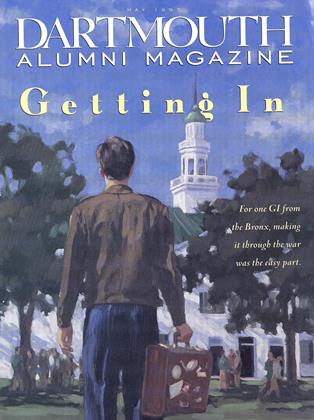

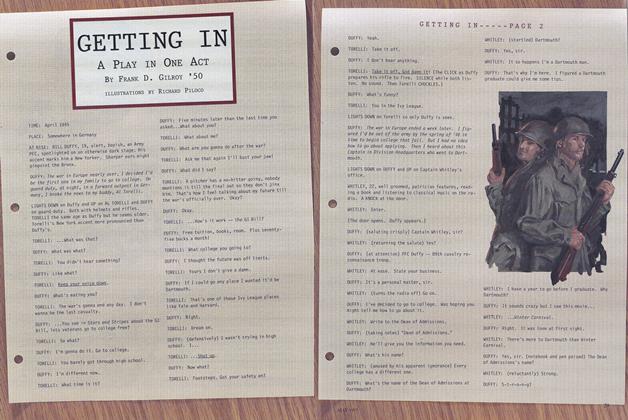

Cover StoryGETTING IN

May 1997 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureDon't Call Me A Pundit

May 1997 By DIANE CYR -

Article

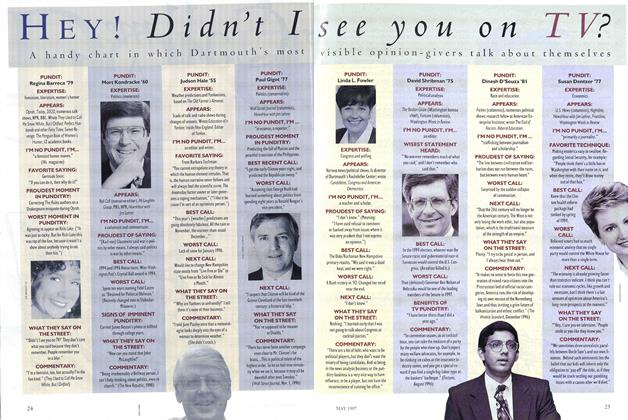

ArticleHey! Didn't I See You on TV?

May 1997 -

Article

ArticleCold Calculations

May 1997 By Christopher Kenneally 81 -

Article

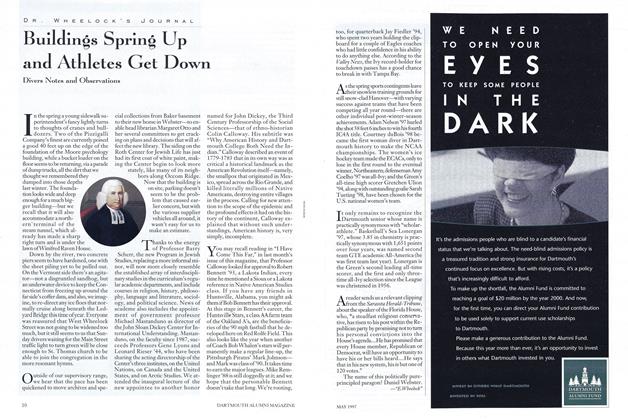

ArticleBuildings Spring Up and Athletes Get Down

May 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1997 By Jeffrey Boylan, Jim "Wazoo" Wasz

James Wright

-

Article

ArticleThe Best of Both Worlds

DECEMBER 1998 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleBuilding Community

APRIL 1999 By James Wright -

Article

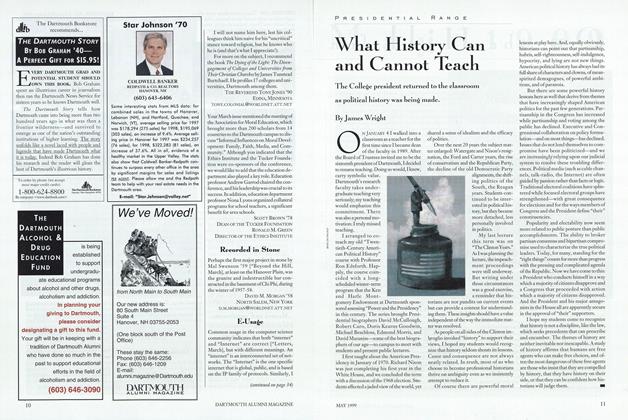

ArticleWhat History Can and Cannot Teach

MAY 1999 By James Wright -

Article

Article"Quite a Group"

Sept/Oct 2005 By JAMES WRIGHT -

Feature

FeatureBattle Scarred

Sep - Oct By JAMES WRIGHT -

notebook

notebookGood Neighbor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JAMES WRIGHT

Features

-

Cover Story

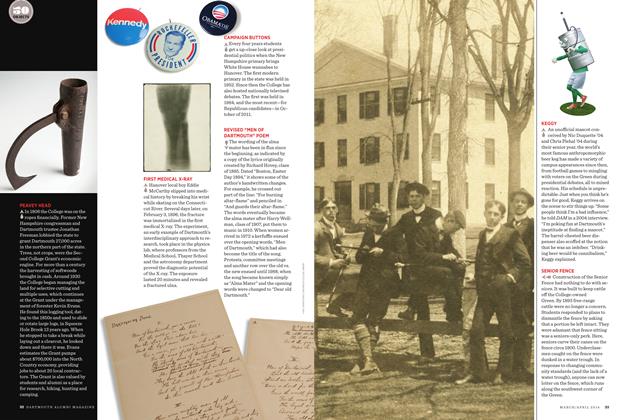

Cover StoryCAMPAIGN BUTTONS

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

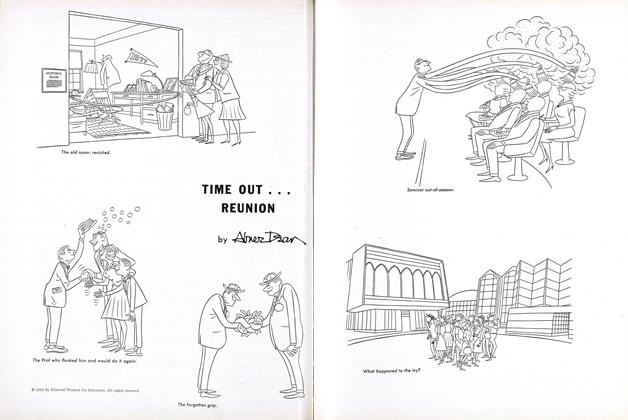

FeatureTIME OUT ... REUNION

JUNE 1963 By Abnez Dean -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

SEPTEMBER 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Cover Story

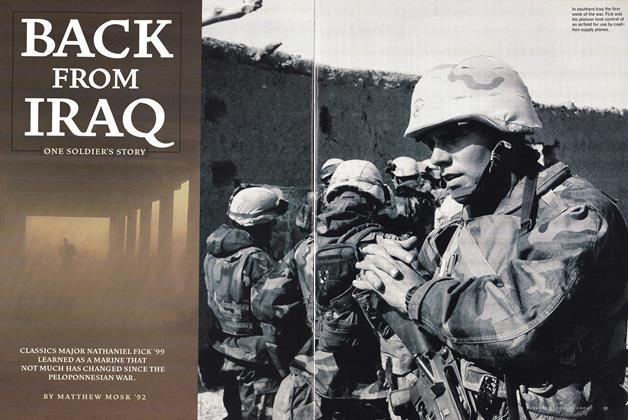

Cover StoryBack From Iraq

Jan/Feb 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureBlack in the White Academy

May 1975 By WARNER R.TRAYNHAM