Dartmouth professors and alumni are speaking outon President Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative

These words, spoken by a little girl, are symbolic of things being said on both sides of the issue of President Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative - perhaps the most technologically complex and morally demanding question of our day.

Symbolic because they are persuasive words, partisan words, words that are meant to scare us and soothe us at the same time. Symbolic because they are part of a TV advertisement that uses for illustration no careful arguments or clear graphs, but an animated child's drawing in five bright colors.

Groups promoting "Star Wars" (or SDI) and those opposed to it are both making statements as manipulative as this one. Presumably, we will be touched by a little girl's summary of SDI or by the little boy in a competing ad frightened of "Space Wars," and after deciding who is more convincingly afraid, make up our minds: we will judge whether Congress should spend billions of dollars for research leading to deployment of a spacebased system designed to protect us from nuclear destruction.

One reason for these crayon-colored campaigns is the confused picture two years of scientific debate have created in the public mind. Dartmouth physics professor David Montgomery gave a talk on Star Wars at last spring's Academic Honors Dinner. He described the atmosphere since Reagan's first mention of SDI in March 1983: "A whirlwind of technical claims and counterclaims about Star Wars/ SDI swirls around in the media, and even the educated part of the public finds it difficult to know whom to believe. Groups with pre-conceived political agendas search for gurus with good scientific addresses who will help them to produce media-releases of a kind they like."

Realizing how important it is to get information to a voting public in a serious (but not completely daunting) manner, Montgomery and other members of the Dartmouth community have begun to focus energy on the war of laser-like words that will determine if we are to have lasers themselves. Sometimes the words are deceptively simple, sometimes falsely complex; at other times they are simply false.

Although people at Dartmouth (and around the country) are taking positions on both sides of the issue, there is a sense of underlying agreement that misconceptions are the biggest barricade in the national debate so far. "Depending on how you phrase survey questions on the subject," says Greg Fossedal '81, a leading pro-SDI publicist, "you can get any number of different answers from people."

Montgomery, a plasma physicist with an international reputation, came to Dartmouth from William and Mary in 1984. He is an articulate opponent of President Reagan's program. Joining him in opposition is fellow faculty member Jay Lawrence, a solid-state physicist who circulated a national petition at Dartmouth calling for a boycott of Star Wars research. Sixty-five percent of the College's physics and chemistry professors have signed the circular, a percentage very close to that at other top universities.

Earth sciences professor Robert Jastrow and Wall Street Journal editorial writer Fossedal are two of the biggest names on the pro-SDI billboard across the political fence. Jastrow, the founder of NASA's Institute for Space Studies, is the author of a book defending the cause to the average reader, and has been a sometimes devastating critic of the calculations of the anti-Star Wars Union of Concerned Scientists. Fossedal, 27, one of the founders of TheDartmouth Review, has been called "the foremost practitioner of conservative journalism" by The Washington Post and is widely said to have influenced (as well as briefed) President Reagan on SDI.

Attempting to create an organized public dialogue between these two camps (or at least hold the two sides accountable for their statements) is Professor of Engineering Arthur Kantrowitz, one of the early architects of the Space Program. Kantrowitz sponsored a "science court" at the College last May which put a Star Wars advocate and opponent "on trial."

The strange thing about the debate over whether a Star Wars missile defense would work is that conservatives, who usually bill themselves as cynical realists when it comes to dealing with the Soviet military threat, are suddenly cast in the role of starry-eyed idealists - not only supporting a system that many scientists feel can't be built, but envisioning a world rid of nuclear weapons forever.

Jastrow's book, How to Make NuclearWeapons Obsolete, is dedicated to "the men and women who want to see nuclear weapons disappear from the face of the earth." Fossedal, for his part, exclaims proudly: "I'm happy that we have the bold, forward-looking solution rather than the liberals. That's happening on more and more issues these days. The liberals are the establishment. We are the progressives."

What makes things look even more backwards is Reagan's "whole earth" notion - an idea that the U.S. would share Star Wars technology with the Soviet Union. Some liberals - become cynics - are crying that the President came up with the idea to pull the rug out from under the growing arms control and nuclear freeze movements. Others feel differently. Lawrence remarks: "I think the President is sincere, but I oppose SDI because I don't think it will work as an effective shield for populations in the way he envisioned it. The shared system would require treaties not only forbidding offensive countermeasures, but also reducing current offensive arsenals. Why, then, can't we have such treaties now?"

Whether Reagan's motives are political or private, inspired by the writings of Fossedal or the estimates of scientists like Jastrow, Star Wars has become such a significant item on the national agenda that if a Dartmouth freshman walks into Baker library and scrolls through microfiched magazine articles, he or she will find the topic more trumpeted than AIDS, terrorism, or even the budget deficit.

Despite all the fanfare, few Americans understand the President's proposals and what they mean in terms of dollars, defense, and scientific requirements. Says Kantrowitz: "In Jefferson's time people could understand all the technical questions. Now we have to delegate these to scientists, but we also need to check up on them."

What is "Star Wars" after all - besides a Spielberg movie - and why does the President say we need it so badly? Even if we can't know everything about a complicated issue, shouldn't we at least try to wrestle with as many aspects of it as we are able?

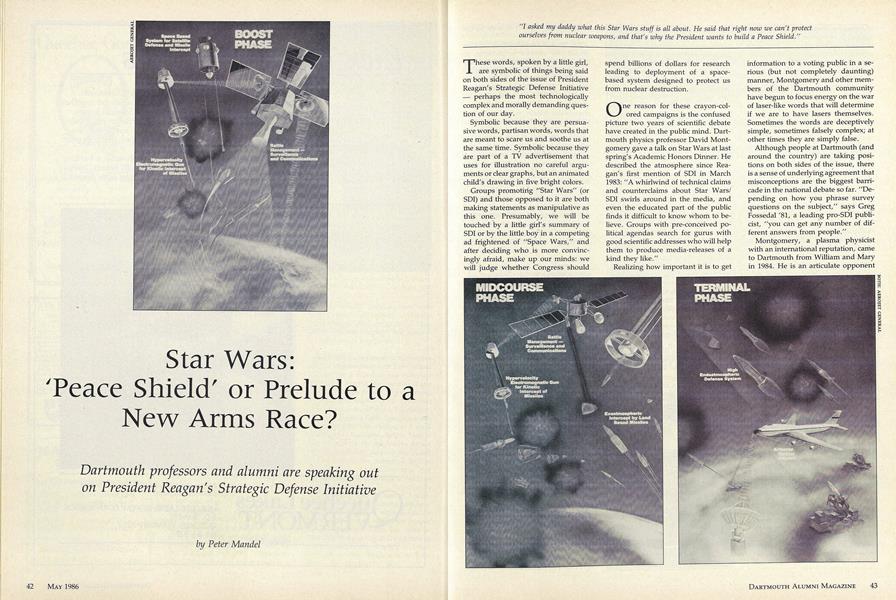

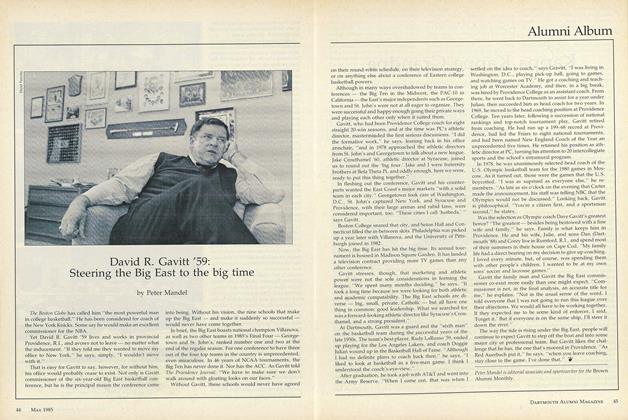

Briefly, a strategic defense system would use various technologies to knock Soviet ICBMs before they reached the United States. Most of the scenarios involve "battle satellites" stationed in orbit that would warn of an attack and fire either laser beams, particle beams, or homing devices at the missiles. Ideally, missiles would be pierced shortly after they took off - they are easiest to spot during "boost phase" and if struck, all of their warheads would be lost. However, SDI proponents envision a layered defense that would also pick off enemy warheads after they split off ("MIRVed") from the booster at the edge of space, and after they re-entered the atmosphere to head toward their targets. This would be considerably more difficult, as warheads are hard to find and even harder to distinguish from decoys that would surely accompany them.

Technical worries, like the decoy problem, pop up like so many jacks- in-the-box. Jastrow believes we have the technology now to put up an effective defense based on homing projectiles or "smart" bullets. However, in his book he calls advanced defense weapons like the laser and the neutral particle beam "exotic technologies." Montgomery, for once, agrees: "We do not have a laser gun or particle gun that would stop an incoming fleet of pick-up trucks, let alone a fleet of missiles."

Other sobering objections include the need for a computer program with at least 10 million lines of error-free code - something that has never been approached; the inability to test the system under wartime conditions; the prospect of lasers starting fires on earth; and the vulnerability of satellites to "space mines." Science guru Carl Sagan has pointed out that even if the shield were 90-percent effective it would still allow enough missiles through to do unacceptable damage.

Given these risks (among others), why the perceived need for a Star Wars defense? Proponents enjoy sinking their teeth into this question. After all, how many people - including staunch opponents of SDI - feel truly comfortable with the uneasy nuclear standoff we have oday?

Fossedal, who calls himself the "muse of the SDI movement, not the philosopher," sounds suddenly philosophical on this subject. "What most attracts me [to SDI] is that it's a morally superior doctrine - to defend people rather than threatening to blow them up." Jastrow's advocacy is rooted in two strongly held convictions: that the restraining fear of mutual assured destruction (MAD) has had "the stuffing knocked out of it" by the recent Soviet military buildup, and that the Soviets are hard at work on their own Star Wars program.

Jastrow says: "These guys have a first strike arsenal, we don't. We can hardly put a dent in their attack force; there is a false perception of symmetry in our arsenals. The perception that the decision on whether to go ahead with SDI rests with the U.S. is also false - the Soviets will have one whether or not we deploy.

"Even if the Soviets didn't have ten times the number of scientists working on this, even if they were not spending $40 billion on total strategic defense, I'd still be concerned about the erosion of mutual deterrence by their landbased missiles."

The debate over Star Wars is as much a strategic and political contest as it is a technical one. Philip Anderson, professor of physics at Princeton and one of a number of Nobel laureates to oppose the program, has remarked - rather rakishly - that most of the scientific issues that come up in talking about Star Wars require very little specialized knowledge.

Fossedal goes as far as to declare that it is not a scientific debate at all. Within it, he says, the most important weapons are ideas. There may be some disagreement on technical details, Fossedal admits, but he feels the larger score will be settled out of the laboratories: "The debate is political in that it has to do with the utility of defenses that people generally agree are plausible. Whether, if you have a certain degree of effectiveness [in stoppoing missiles], such a system should be deployed. Jastrow says yes, Sagan, no."

Lawrence believes the technical and political questions are best described as being "coupled." Given a technically realistic picture of what SDI can actually do, one must raise the political question whether it is likely to improve our security, or in fact lessen it by aggravating the arms race. Many people, including signers of the petition, believe the latter."

A good example of the strategic side of SDI is the old quandry of football coaches chalking their X's and O's: who has the natural advantage - crafty offense or flexible defense?

Montgomery speaks for the former: "To think that all possible avenues of weapons delivery can be anticipated and guarded against 24 hours every day seems to me to be the grossest delusion ... Anticipating all possible means of delivery is really only a technically soluble problem if your opponent lacks imagination." His colleague, Lawrence, adds: "If you make estimates on how well a Star Wars defense will work, you have to make assumptions about the offense. It's like planning for a shutout in the Super Bowl. By the time SDI is in place, those assumptions will no longer be valid. Offensive countermeasures are relatively cheap and quick compared with Star Wars."

In reply, Jastrow argues that, in the case of a large-scale nuclear confrontation, uncertainty is more paralyzing to the offense than the defense. "Contemplating a first strike, the Soviets must be sure they will cripple our retaliatory power. A Star Wars defense, even by conservative estimates, will insure that we have a means of retaliating and this will give Soviet planners some thought."

Jastrow peers across the line of scrimmage to make his point. "A prominent authority," he says, "has indicated that offensive adjustments to our defense will not be viable that is, Gorbachev. His side is telling him: 'Boss, defense is very effective.' If it weren't, the Soviets wouldn't study defense themselves and by their silence they would encourage us to go ahead and spend our money."

With so many words arching like missiles and aiming at each other like ABMs, one might wonder if there is anything at all the two sides can agree on. The surprising answer seems to be yes. One such occasion took place at Dartmouth last May 24 when Edward Gerry, a member of the Defense Technologies Study Team advising President Reagan, and Richard Garwin, a physicist and SDI critic, squared off in court - science court, that is.

Hemingway look-alike Arthur Kantrowitz and other key Dartmouth professors have long supported the idea of a science court or "scientific adversary procedure" as a way of edging us back to Jefferson's time and making scientific spokesmen once again accountable to the public and to other scientists. The process, which includes sorting out agreed and contested propositions and cross-examining, is meant to put the public back in the thick of science-related policy.

Last May, Kantrowitz was "absolutely flabbergasted" to find out how often his "adversaries" agreed. "We didn't expect so much agreement," he says. "As a matter of fact it was embarrassing. We had an open session in the afternoon and since we had spent the morning agreeing, there was almost nothing to talk about." Although Gerry and Garwin didn't leave the sessions arm in arm, they did get together on fifteen statements. Among them:

• No viable defensive system can allow space mines to be placed within lethal range of space assets. Countermea- sures are a fundamental problem to the success of a highperformance strategic defense. The SDI program is exploring possible solutions to all of the countermeasures issues which have been raised publicly and more.

While these are hardly breakthrough propositions, they are at least a start in bridging gulfs that break up the issue of Star Wars - the gulf between those who support it and those who oppose it; the gulf between high-tech pronouncements and public understanding; and, perhaps deepest of all, the gulf between a serious, clearheaded policy debate and an irresponsible public relations war.

"The only happy ending that I can see in this business," says Kantrowitz, "is a new openness. At this stage, anyone who says SDI will be successful- or will not be - is arrogant. I think the assertions that the system can be outfoxed or can't be are both misleading. If I have to bet my life, I will bet it on the free marketplace of ideas and research."

Since all of us will be wagering along with Kantrowitz, and along with Lawrence and Fossedal, Montgomery and Jastrow, we must choose to ignore what comes out of our TVs during commercials, and turn up the sound when we hear the gavel banging in a science court or a Senate hearing. As citizens in a democracy, it is one of our duties to be educated. It is also our only legitimate hope.

Earth sciences professor Robert Jastrow isone of several Dartmouth figures who havespoken out nationally on "Star Wars."

I asked my daddy what this Star Wars stuff is all about. He said that right now we can't protectourselves from nuclear weapons, and that's why the President wants to build a Peace Shield."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

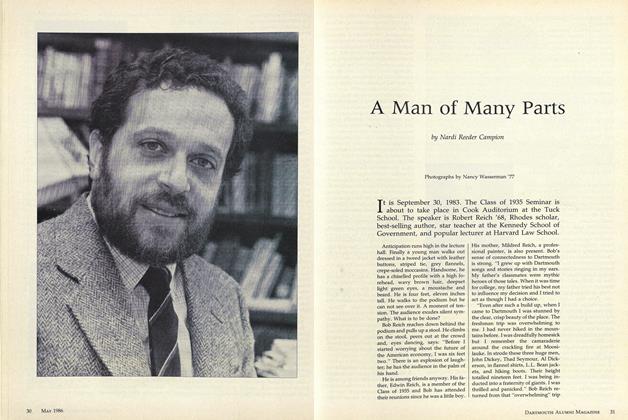

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

May 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleBack where it all began: Al McGuire at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Jim Kenyon -

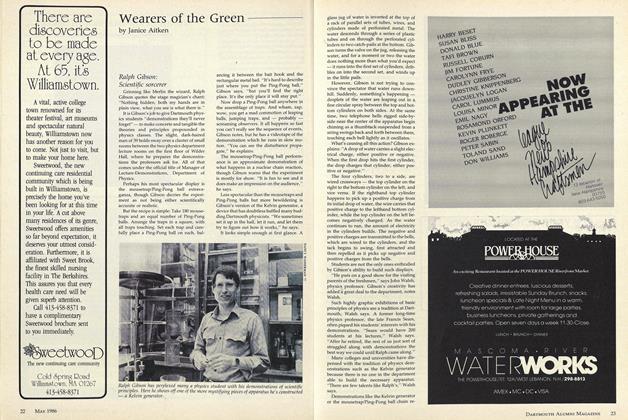

Article

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

May 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

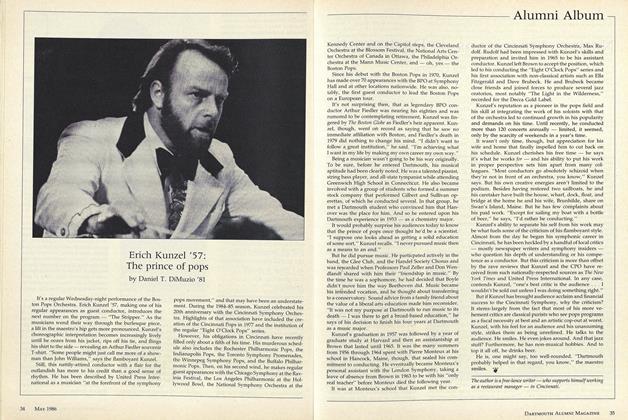

ArticleErich Kunzel '57: The prince of pops

May 1986 By Daniel T. DiMuzio '81 -

Article

ArticleRick Monahon '65 restores the past while enriching the future

May 1986 By WILLIAM MORGAN '66

Peter Mandel

Features

-

Feature

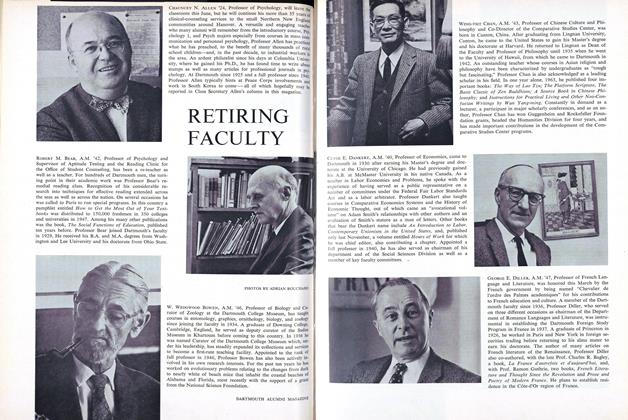

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1966 -

Feature

FeatureEnergy: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

April 1974 -

Feature

FeatureMatthew Wysocki Professor of Art 300 St. Nicks in D single collection

January 1975 -

Cover Story

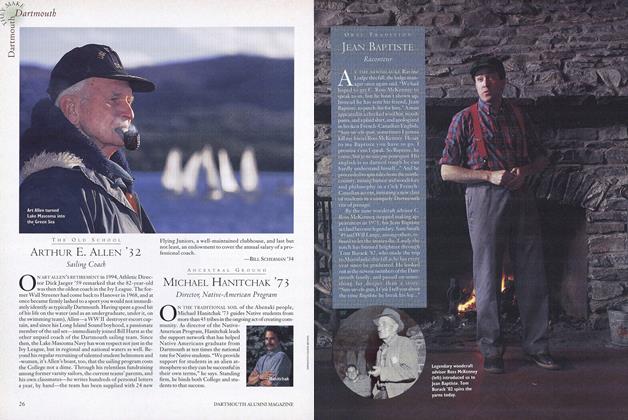

Cover StoryMicheal Hanitchak '73

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

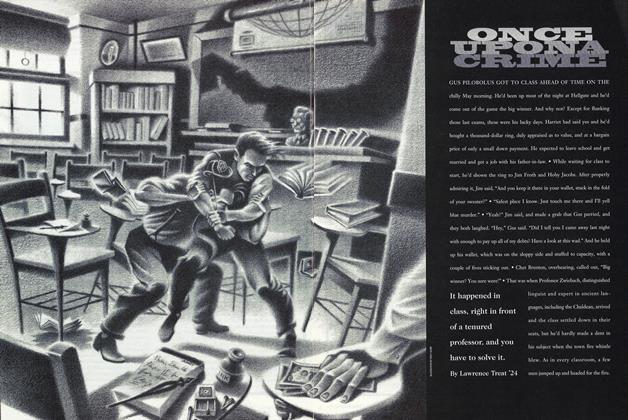

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

FEBRUARY 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

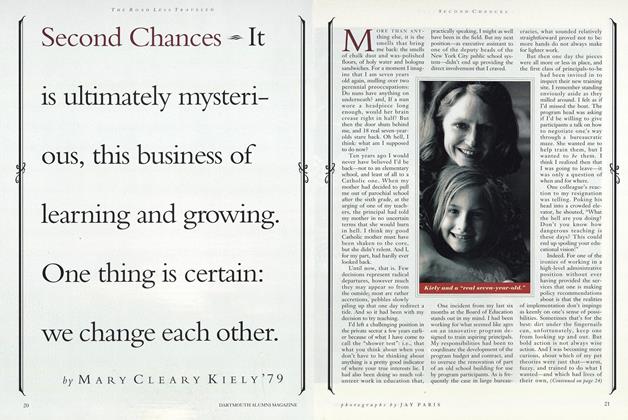

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79