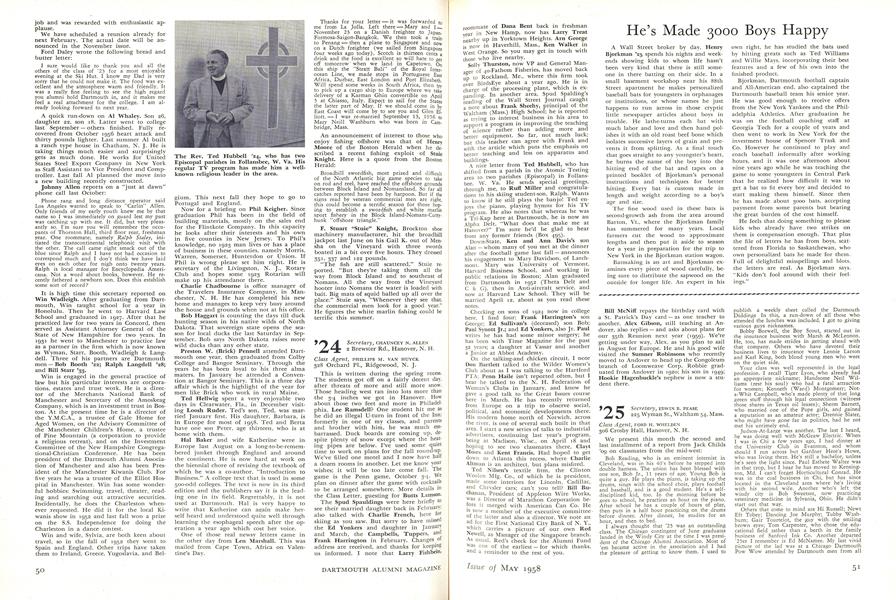

A Wall Street broker by day, Henry Bjorkman '25 spends his nights and weekends showing kids to whom life hasn't been very kind that there is still someone in there batting on their side. In a small basement workshop near his 88th Street apartment he makes personalized baseball bats for youngsters in orphanages or institutions, or whose names he just happens to run across in those cryptic little newspaper articles about boys in trouble. He lathe-turns each bat with much labor and love and then hand polishes it with an old roast beef bone which isolates successive layers of grain and prevents it from splitting. As a final touch that goes straight to any youngster's heart, he burns the name of the boy into the hitting end of the bat and tapes on a printed booklet of Bjorkman's personal instructions and techniques for better hitting. Every bat is custom made in length and weight according to a boy's age and size.

The fine wood used in these bats is second-growth ash from the area around Barton, Vt.. where the Bjorkman family has summered for many years. Local farmers cut the wood to approximate lengths and then put it aside to season for a year in preparation for the trip to New York in the Bjorkman station wagon.

Batmaking is an art and Bjorkman examines every piece of wood carefully, being sure to distribute the sapwood on the outside for longer life. An expert in his own right, he has studied the bats used by hitting greats such as Ted Williams and Willie Mays, incorporating their best features and a few of his own into the finished product.

Bjorkman, Dartmouth football captain and Ail-American end, also captained the Dartmouth baseball team his senior year. He was good enough to receive offers from the New York Yankees and the Philadelphia Athletics. After graduation he was on the football coaching staff at Georgia Tech for a couple of years and then went to work in New York for the investment house of Spencer Trask and Co. However he continued to play and coach baseball informally after working hours, and it was one afternoon about nine years ago while he was teaching the game to some youngsters in Central Park that he realized how difficult it was to get a bat to fit every boy and decided to start making them himself. Since then he has made about 3000 bats, accepting payment from some parents but bearing the great burden of the cost himself.

He feels that doing something to please kids who already have two strikes on them is compensation enough. That plus the file of letters he has from boys, scattered from Florida to Saskatchewan, who own personalized bats he made for them. Full of delightful misspellings and blots, the letters are real. As Bjorkman says, "Kids don't fool around with their feel ings."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThree Civil War Letters

May 1958 By WILLIAM D. HARTLEY '58 -

Feature

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1958 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleWhat Is "New" in the Program?

May 1958 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28

Article

-

Article

ArticleX-RAY MACHINE FOR THE HOSPITAL

November, 1914 -

Article

ArticleA Mission for Civil Rights

JUNE 1964 -

Article

ArticleONE STUDENT TYPE GONE

October 1943 By George H. Tilton III USNR -

Article

ArticleGetting In and Out of Hanover 60 Years Ago

DECEMBER 1967 By John R. Scotford '11 -

Article

ArticleSTUDENT CONTROL

April1935 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2003 By Peter Michael Gish '49