WHEN the railroads monopolized transportation Hanover was a long way from anywhere. The journey to college was not to be taken lightly and unadvisedly but soberly, discreetly, and in the fear of God.

On Sunday, September 22, 1907, at 3:30 p.m., I boarded a Pullman on a Grand Trunk train leaving Chicago. With me were three other freshmen: Eugene Fuller, Ben Stout, and Sherwood Trask. A senior, Herbert H. Mitchell '08, kept a discreet eye on us, but somehow stayed out of sight most of the time. Monday morning we had an hour and a half in Toronto and that night two hours and a half in mysterious Montreal. At 3:30 Tuesday morning we were ejected from our berths at White River Junction where we waited until six when a train went up to the Norwich-Hanover station to get anyone who wanted to go to Boston. The train fare was $19 and the Pullman, which we occupied one and a half nights, $5.50.

We made better time going home. You could get the same Pullman on its return trip at the Junction at 4 in the afternoon, which would put you in Chicago at 9 the next night, or you could go down the valley, leaving just before noon, and catch a Pullman at Greenfield which arrived in Chicago in the late afternoon.

This hiatus of 30 to 40 hours between campus and home permitted a leisurely approach to the somewhat painful adjustment between the new personalities we were sprouting in Hanover and the old juvenile personalities we had to sink back into when we rejoined our families.

The most imposing feature of the trip down to New York was the ticket, which consisted of a contract and six coupons with a total length of over a foot. The Boston and Maine got you to White River where the Central Vermont took over to Windsor. There the B&M resumed as far as Brattleboro, where responsibility passed to the CV until you reached South Vernon Junction and you fell into the hands of the B&M once more and stayed with them as far as Spring-field where the New York, New Haven and Hartford assumed responsibility for getting you to New York. Fortunately, the engine and the train crew seemed unaware of the alternating ownership of the track and pushed on through to Spring-field, where you usually changed cars.

The real obstacle to getting down the valley were the junctions, of which there were six - White River, Claremont Junction, Bellows Falls, Brattleboro, Greenfield, and Springfield. In those days railroad protocol required a train to stop for at least twenty minutes at every junction. Even at that, by leaving Hanover before noon you could get to the bright lights of Broadway before bedtime.

The only real event on the way to Boston was the station at Concord, which was a perfect expression of all things Victorian. This was not only the transportation hub for New Hampshire, with six radiating lines, but it was also the seat of real power in the state. While governors came and went every two or four years the decisions that counted were made in the upper part of the station by the legal representative of the Boston and Maine, General Frank S. Streeter '74, a great hulk of a man with a perfect poker face and an enduring love of Dartmouth College.

Even places near at hand were practically far away. During my junior year I preached a dozen times at North Pomfret, Vt., which is 18 miles from Hanover by highway and rather less by air. But here was my procedure: Leave Hanover before noon on Saturday; eat lunch at the Junction House for fifty cents, which was served with one plate but a whole flock of little sauce dishes; take the 2 o'clock Central Vermont train to West Hartford; ride the mail stage to North Pomfret, with the driver dropping me off wherever I was to stay for the weekend. The return journey began after Christian Endeavor on Sunday night with a walk of four miles down the hill to West Hartford, where I flagged a late train by igniting a newspaper in its path. This got me to the Junction where I could have a room to myself for 75¢ or share a double for 50¢. All the rooms smelled of sour apples. The next morning I caught the 6 o'clock train to Hanover.

The most flexible way of getting around was by horse and buggy - or sleigh. Hanover boasted three livery stables: Hamp Howe's major establishment just off Main Street and two lesser places on Lebanon Street. Rates were set by the distance rather than by the hour. You could charter a rig for the Junction and back for $1.25. If you kept the horse out all night you were expected to feed it.

Driving a horse is a more subtle business than operating a motor car. Every horse had a personality and ways of its own. But once you had "worked the combination" you could relax, with the situation inviting good talk. Some of these trips were memorable. On a glorious fall day in 1908 Charles W. Cartland '09 and I drove over to Meriden, N. H. We decided to have supper at Kimball Union Academy, then a coeducational institution. While we were waiting in the parlor, girls would peek in the door, giggle, and run away. We were served in a private dining room by a self-conscious waiter. When we offered him a tip, he replied, "You pay in the office!" Once Billy Hint '12 and I left for North Hartland, Vt., after breakfast on Sunday morning and did not get back until just in time for chapel at 5.

Sleighing was wonderful, but had its problems. Once Fletcher Clark '12 and I took off for an evening affair at Sharon, Vt., going over the hills by way of Beaver Meadow. On the way back we went astray into a barnyard and had to wake up a very sleepy farmer to get directions. We were supposed to turn right at a pond, but it was not only frozen but snow-covered. Turning a horse and sleigh around in deep snow was something of a trick. While Fletcher held onto the horse, I picked up the sleigh and rotated the whole shebang 180 degrees.

Automobiles came late to Hanover. Some men were brought to town by car, or gotten in the spring, but the common idea was to get out of town before the temperature dropped or snow fell. The richest man in college was reputed to be Chase Keith Pevear '10, who had two claims to distinction: a suit made of green corduroy and a motorcycle that sounded like a juvenile patriot letting off firecrackers by the bunch on the Fourth of July. Not until 1908 or 1909 did a car actually winter in a shed out near St. Denis Church - and it probably was well drained and jacked up. The first respectable citizen to buy a car was Richard Wellington Husband, Professor of Greek.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFood for Alumni Thought

December 1967 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth-Talladega Alliance

December 1967 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

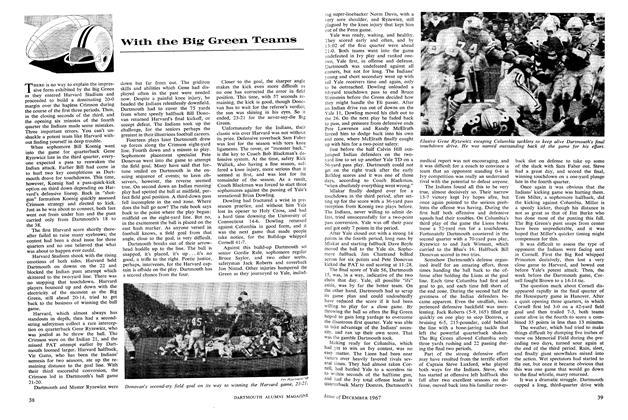

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1967 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1967 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE R. MINER, TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

December 1967 By EARL H. COTTON, LOUIS A. YOUNG JR.

John R. Scotford '11

-

Letters to the Editor

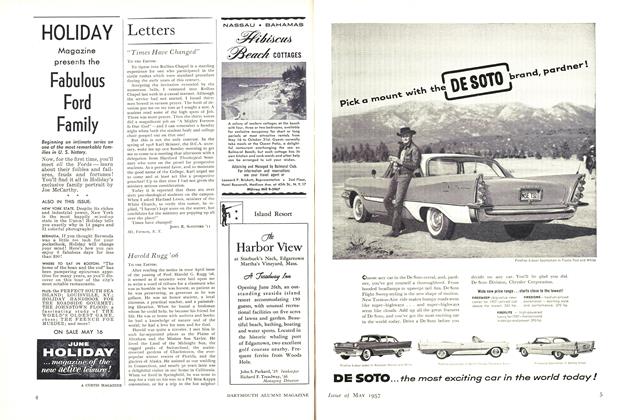

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY 1957 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

DECEMBER 1963 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JANUARY 1969 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1971 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1975 -

Article

Article"Where We Really Feel at Home"

FEBRUARY 1967 By John R. Scotford '11

Article

-

Article

ArticleTrustee Scholarships

October 1941 -

Article

ArticlePied

April 1975 -

Article

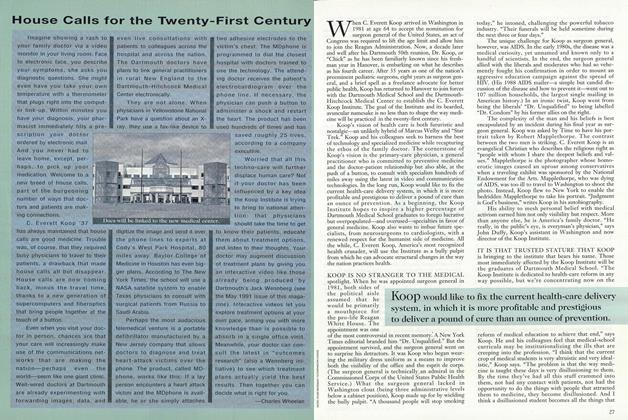

ArticleHouse Calls for the Twenty-First Century

NOVEMBER 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleAn Appreciation of Music

MAY 1931 By Donald E. Cobleigh -

Article

ArticleHOCKEY

APRIL 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleSTUDENT-ALUMNI CONTACTS

April 1934 By Thomas H. Lane '35