From Dartmouth's Baker Collection—

WHEN a man leaves his family, the letter becomes a valuable and important means of communication between him and his home. When a man leaves his family and goes to war, the letter becomes something more: it becomes his life, his link to the world he knows and loves, and his means of escaping from the unfamiliar scenes into which he has been thrust.

A letter from a man at war reveals much about his character, emotions, and philosophy. Through a war letter, we can see a man as he is - completely devoid of superfluous and disguised trappings. For all its evils, war is a great cleanser and equalizer; all men bare their true selves in time of national and personal conflict.

First of all, there was the Major. He wrote to his wife many years ago. He may have been sitting in a tent with a small candle or oil lamp flickering across the paper on which his quill pen was scratching. He may have been out in the warm summer's night, huddled close to the fire so as to receive its greatest light. It makes little difference now —as little as it did then - where or how the Major wrote. In writing to his wife, he was reestablishing the tenuous link to his home and he was telling her of the battle he soon must enter - the battle of Bull Run.

"My very Dear Sarah," he began. He may have paused, as do all letter-writers, collected his thoughts over the muted sound of cannon exploding in the distance, and then continued: "The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days, perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write you again, I feel impelled to write you a few lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more. Our movement may be one of a few days and full of pleasure and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. ... If it be necessary that I should fall on this battlefield ... I am ready. I have no misgivings about or lack of confidence in the cause in which I am engaged and my courage does not halt or falter.

"I know how strongly American civilization now leans on the triumph of the government and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and sufferings of the revolution. And willing I am, perfectly willing, to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain the government and to pay that debt. But, my dear wife, when I know that with my own joys I lay down nearly all of yours and replace them in this life with cares and sorrows, when after having eaten of the bitter fruit of orphanage myself I must offer it as the only sustenance to my dear little children, is it weak or dishonorable that while the banner of my purpose floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, underneath my unbounded love for you, my darling wife and children, should struggle in fierce though useless contest with my love of country?

"I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer Sabbath night when two thousand men are sleeping around me - many of them enjoying the last before that of death, and I am suspicious that death is creeping behind me with his fatal dart and communing with God, my country, and thee. I have sought most closely and diligently and often, in my breast, for a wrong motive in this hazarding the happiness of all those I loved and I could find none....

"Sarah my love, love for you is deathless. It seems to bind me with mighty cables that nothing but omnipotence can break. And yet, my love of country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battlefield. The memories of all those blissful moments I have spent with you come creeping over me and I feel most grateful to God and to you that I have enjoyed them so long. And how hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years when, God willing, we might still have lived and loved together and seen our sons grow up to honorable manhood around us.

"I know I have but few and small claims on Divine Providence but something whispers to me. Perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you and when my last breath escapes me on the battlefield it will whisper your name. Forgive my many faults and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless and how foolish I have often times been.... But O Sarah, if the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen among those they loved, I shall always be near you in the darkest night and in the gladdest days, amidst your happiest scenes and gloomiest hours always, always, and if there be a soft breeze upon your cheek, it shall be my breath. Or as the cool air cools your throbbing temples, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah, do not mourn me dead. Think I am gone and wait for me for we shall meet again."

He forecast his death and his prediction was true. Two days later, a bullet, or a piece of shrapnel, or some other death-dealing object took Major Sullivan Ballou from his wife Sarah and his small children. The letter, however, did not die with him. It went on its journey from Camp Clark to Rhode Island, bringing first elation, as the family saw the envelope from husband and father, and then sadness when they read the contents. The Major was dead; his family eventually grew, lived its life, and died. But the letter remained. The few scratched ink lines on flimsy paper that transported this man home to his family remained over the years gathering dust, turning yellow, but still containing the feelings, the emotions of one man as he entered the battle that was to claim him.

Today that letter rests in a modern steel file cabinet in the College Archives in Baker Library. We read in the glare of fluorescent lighting what was written in the soft glow of an oil lamp or camp fire. Few have any idea how the letter came from Rhode Island to Hanover; few seem to care. The small details in the life of this letter make little difference.

What is important, rather, is what it says. Major Ballou is equating his love of country and his love of family. When war comes to a country, the peaceful man must make a choice between principle and the calm, serene life. The Major made his choice and he died for it. He didn't want to die; he didn't even want to go to war. But his sense of duty prevailed and he fought for the cause in which he believed.

AND then there was the boy named Roger. Roger didn't look at war in the same light as Major Ballou. To Roger, war was a big game in which he could carry a gun and wear a uniform and have a duty. Roger was proud of this gun and uniform and of the army in which he fought. Roger had yet to see a battle from which men walked away with dirty and bloody uniforms - if they walked away at all.

"The regiment to which I belong makes no advances as yet with the rest of our army," he told an aunt who seems to have been pestering him for the details of his new-found glory. "The cause of it, however, is said to be not that they have little confidence in us but because they have so great a need at headquarters, giving us the duty to do and the position of the regular U.S. troops. I confess it would seem to me to be the highest honor (Roger's italics) to advance, but I suppose they want good drilled troops about Washington to act as a reserve force. I suppose we shall remain until our army makes such advances and successes as places Washington safe beyond a doubt and then be advanced to conduct siege operations as heavy artillery. The company I belong to was detailed about a week ago to come here and do guard duty on the Virginia half of Long Bridge. It is three-quarters of a mile long and is mined so that it may be instantly destroyed. Our duty is to see that only a certain number of teams, cattle or troops pass over at a time and that everything goes no faster than a walk and also that no man smokes upon it. Besides, every man has to have a pass in the daytime or the countersign at night or he can't pass and is arrested." Here is the epitome of war for Roger - the countersign!

"When I was at your house and after, the rebels held this half of the bridge that we now guard," he continued. "They had all of Arlington Heights where our forts now are. I hear that there is some impatience that McClellan does not move faster. Give him his time, our patience, and our prayers. Let not the impatience come again from those who are not the actors in these trying scenes which must be historical. Let us all have the faith we soldiers have in what he has said: 'We are to have no more Bull Run fights, no more retreats and no more defeats.' I believe the morning sun of the fourth of July, 1862 shine upon the 'starry banner' floating from Fort Sumpter and from every Place throughout our land from whence it has been torn down."

Roger didn't know Major Ballou. He didn't even know that the Major died in the battle McClellan spoke of. Roger seems even not to know what the battle was about; he knows only that his general has said there would be no more of its kind; he knows that he is an "actor" in "these trying scenes"; and he has the satisfying knowledge that he is participating in the fashioning of history.

We don't know what happened to Roger; there are no more letters over his name. He may have stayed with his regiment and guarded that bridge and asked for the countersign for the rest of his army career, or he may eventually have gone into battle and experienced war as it really is. If he did go to war, we can be sure that he never became as resigned to it as did the gentleman by the name of I.C. Perkins.

MR. PERKINS was in the siege of Vicksburg and it is obvious that he was tired of the siege, of the battle, and of the whole war. The sound of exploding cannon bothered this soldier; it took him quite a while to get used to sleeping with artillery firing around him.

"We still hold our position only we have advanced our lines nearer to the enemy and planted siege guns nearer to the enemies forts. We now have them inside of their fortifications and we will try and keep them there until they surrender. The question might be asked why we do not take Vicksburg by storm at the point of the bayonet. Persons asking such questions would understand the reasons if they could be here and see how strongly Vicksburg is fortified. We could probably take the place by storm but not without losing from 10 to 15 thousand men. The enemy has done but very little firing during the past week. From all appearances they are getting short of ammunition as well as rations. Our line of battle extends from the Mississippi River on the north of Vicksburg to the Mississippi River on the south. And our gun boats and mortars [are] in front. If you could have been here and heard the roar and bellowing cannons from the commencement up to the present, you would probably by this time be able to sleep sound at the mouth of a 64-Ib. gun....

"Our camp is in range of the enemies forts, and our piquet lines are within short grape and canister range; and in some places on our lines... our men are close up under the enemies guns and the enemy dare not show their heads. Of late, the rebel General Johnston made an attempt to reinforce Pemberton but was repulsed by the Yankees, and it is reported that we took 2,000 prisoners from him. There has been but little firing during the past night but they are commencing again this morning. It is now six o'clock. Gun boats and all. It will probably take us some time after this siege is over to get used to go to sleep without the music of the cannons. Some of us did not go to sleep very early last night and some seemed to think that the reason why we could not sleep was because the cannonading had stopped and that everything was so still."

THERE are the three men who fight a war: the peaceful, home-loving man who fights for principle; the youth who goes to battle for the sounds and the glory and romance he feels is involved; and the man who thinks in terms of the professional - cold, tactical, interested only in doing what he has been assigned to do, getting it over with, and going on to the next job. There are others, of course, but these are the main types into which all men who fight a war can fall. Through the eyes of these three, war can be seen in its multifold aspects. Each man sees the same war; each man gives the war a different interpretation.

The world beyond the battlefield knew of the Civil War mainly through the letters of those actively involved in it. But there were other forms of communication not personal but still telling of the war. In the same Dartmouth file holding the yellowed letters of the three men, there lies a small piece of paper, a form of the American Telegraph Company, Boston and White Mountain Section. It was a telegram that brought war home to a Mrs. Dunbar - brought it home far more forcibly than any letter could have done. Dated Washington, December 32, 1862, and marked received in Manchester the next day, it tells a mother, very simply and bluntly: "Stephen Dunbar is dead will be at Manchester Wednesday."

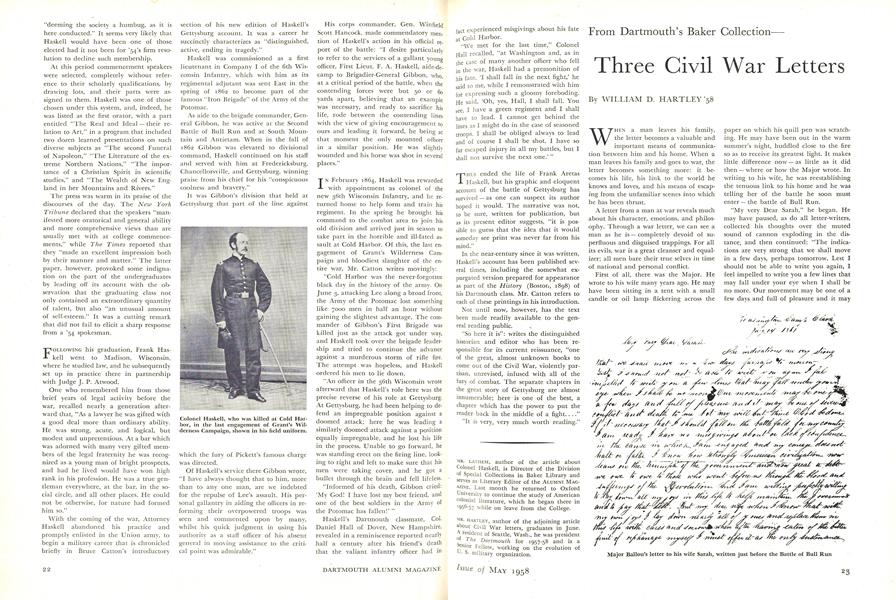

Major Ballou's letter to his wife Sarah, written just before the Battle of Bull Run

Letter written by I.C. Perkins, a soldier engaged in the siege of Vicksburg

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

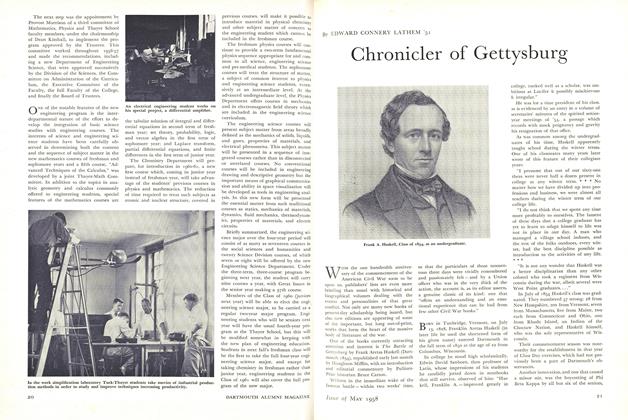

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1958 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

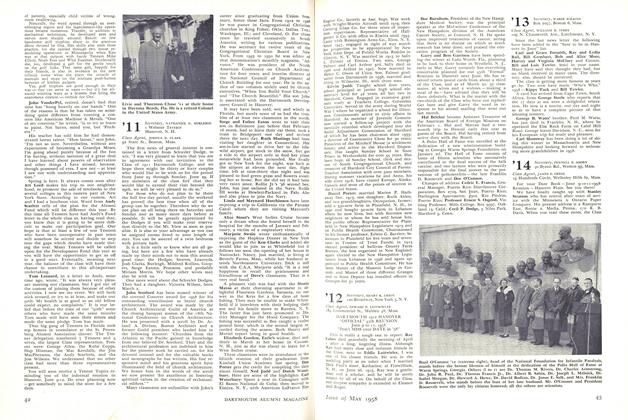

ArticleWhat Is "New" in the Program?

May 1958 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1958 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOED WEEK: A Taste of the Future?

MARCH 1969 -

Feature

FeatureLong Time Coming

July/Aug 2010 By COLIN CALLOWAY -

Feature

FeatureIndividuality in Forest Trees

February 1960 By F. HERBERT BORMANN -

Feature

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

FEBRUARY 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

JULY 1959 By JOHN E. BALDWIN '59 -

Feature

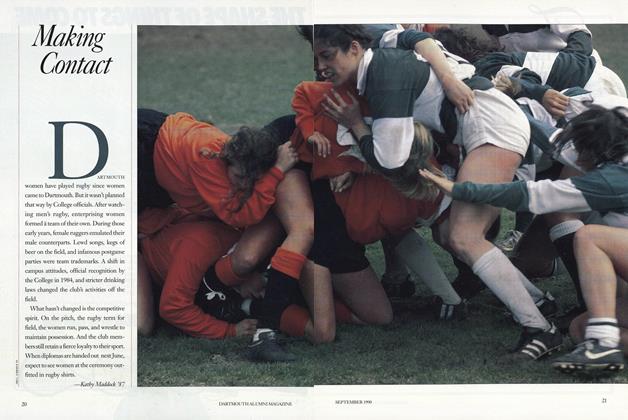

FeatureMaking Contact

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87