1869-1901. ByLeonard D. White '14. New York: Macmillan, 1958. 406pp. $6.00.

The untimely death of Leonard D. White last February makes this the final volume of his studies in the administrative history of the Federal government. It has been a brilliant achievement which was recognized, following the publication of the third volume in the series, The Jacksonians, by the award of the Bancroft Prize, one of the outstanding prizes in the field of American history.

Like its predecessors, The Federalists, TheJeffersonians and The Jacksonians, The Republican Era is based on sound and meticulous scholarship. The author's deep understanding and grasp of his subject is not only evident in the organization of a vast amount of detail, but in his choice of illustrations, his interpretation of salient developments in our Federal administrative history, and in his comments upon, or pen portraits of, significant personalities. Nor is there lacking an occasional touch of humor.

The Republican Era covers the administrative history of the Federal government from 1869 to the advent of Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency in 1901. Administratively it was a difficult period. This was due in the first place to the almost utter collapse of presidential prestige and power during the presidency of Andrew Johnson when control of the government passed into the hands of Congress, and particularly into the hands of a reactionary and spoils-minded Senatorial oligarchy. The President became little more than a figurehead, and the administrative system the prey of the spoilsmen. The domination of this Senatorial oligarchy which found in Grant a pliant tool was finally broken by Hayes and Garfield who restored to the presidency something of its earlier prestige. Further progress was made by Cleveland and McKinley, but it was not until the days of Theodore Roosevelt that the potentialities of executive power were again realized in anything like the measure existing under Jackson and Lincoln.

A second problem in the administrative history of the era was the growing demand for a long overdue measure of civil service reform. In a number of interesting chapters the author discusses the origins of this reform movement, and the success of the reformers, culminating, after the assassination of Garfield by a disappointed office seeker, in the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Act in 1883. There followed a long, and sometimes bitter, struggle to prevent the repeal or emasculation of the act by spoilsminded Congressmen or department heads. In this struggle the power granted the President to extend the coverage of the classified competitive system established by the act played no small part. In the several government departments the progress of reform, discussed by the author in considerable detail, varied, but by the turn of the century it was becoming obvious that a new personnel system striving for political neutrality and emphasizing business administrative techniques and efficiency was gradually replacing the old political domination of the administrative machinery. By the turn of the century, too, public service ethics had improved greatly since the low ebb of the Grant regime. The Civil Service Act encouraged higher standards of official conduct, and for the rank and file of government employees it became less important to secure political support, at whatever cost, as a condition of steady employment. It was more important to earn a reputation for diligence and trustworthiness.

It is a tragedy that Leonard White could not have lived to carry his studies of our Federal administrative history on into the twentieth century when far-reaching transformations in policy and practice were to take place. But his four volumes as they stand constitute an invaluable contribution to the fields of American government and history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

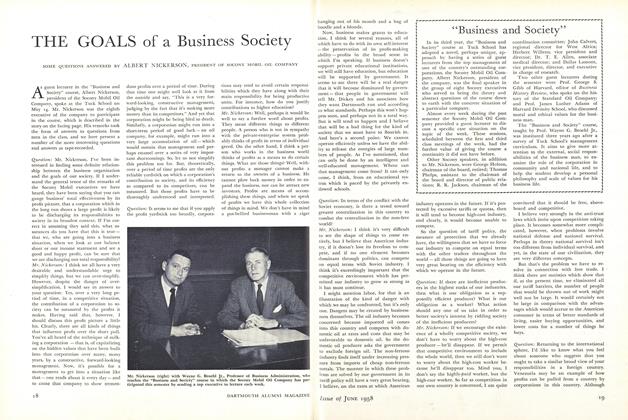

FeatureTHE GOALS of a Business Society

June 1958 By ALBERT NICKERSON, -

Feature

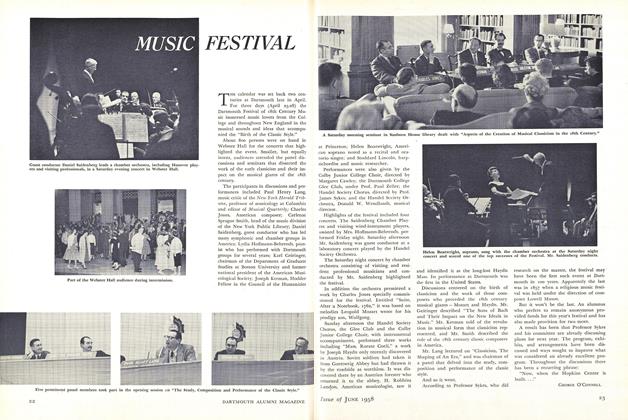

FeatureMUSIC FESTIVAL

June 1958 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

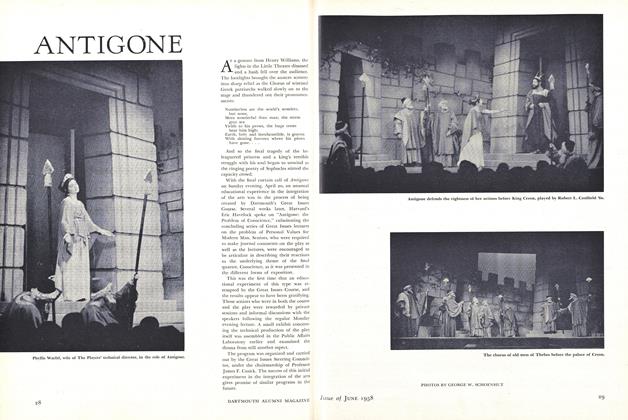

FeatureANTIGONE

June 1958 -

Feature

FeatureMAY: It's Marvelous

June 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910

June 1958 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, ANDREW J. SCARLETT, HERB WOLFF '10

W.R. WATERMAN

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE NEW ARGONAUTICA

December, 1928 -

Books

BooksTHE PSYCHOLOGY OF RADIO

January 1936 By C. N. Allen '24 -

Books

BooksBROTHERHOOD OF MEN

July 1949 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksFIRSTHAND REPORT: The Story of the Eisenhower Administration.

October 1961 By LANE DWINELL '28 -

Books

BooksHISTORY OF GRANVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS.

March 1955 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Books

BooksGAMBLING IN AMERICA

May 1952 By Virginia Close