FREE SPEECH: A PHILOSOPHICAL ENQUIRY by Frederick Schauer '67, TU'68 Cambridge University Press, 1982. 237 pp. $34-50 cloth, $9.50 paper

The importance of free speech is rarely disputed in our country, but there is much dispute about why it is important and when it should be limited. Should we allow political groups to advocate terrorism or assassination? Should we allow hardcore pornography to be sold or advertised in public? Should we allow gossip columns to ruin reputations by printing malicious rumors about our private lives?

Such questions are usually answered by little more than emotional outbursts and simplistic slogans. For more reasonable answers, we need careful, dispassionate analysis of many complex details. A start twards fulfilling this need is made with clarity and insight by Frederick Schauer in Free Speech.

Schauer, a professor of law at the College of William and Mary, argues that we do and should have a right to free speech, but more importantly, he goes deeper to ask what this means. By his account, to say that we have a right to free speech is to say that more justification can be required for restricting free speech than for restricting other activities (such as bathing) to which we have no right. Such rights can vary in strength as well as in coverage.

In order to justify a right to free speech, Schauer then shows how speech is different from other activities in ways that warrant

greater protection. His argument for a right to free speech does not depend on principles of general liberty. Instead, he shows the strengths and weaknesses of traditional arguments from truth, from democracy, from the good life, from autonomy, from utility, and so on. Schauer shows that not all of these arguments apply to all speech, but they jointly make a strong case for free speech in a variety of circumstances. What unifies these arguments is a mistrust of the government's ability to distinguish true speech from false speech, harmful speech from harmless speech, etc.

The considerations in favor of a right to free speech also determine what counts as speech (silent marches? abstract art?), the kinds of restrictions from which we should be free (limits on the choice of texts in schools?), the strength of our right to free speech (when does it override public safety?), and other issues. Schauer argues that just as it is better for ten guilty men to go fee than for one innocent man to be punished, so it is less important to restrict all unacceptable speech than to avoid restricting acceptable speech.

Schauer concludes with applications of his theory to defamation, obscenity, treats to national security, and various styles of speech. He does not pretend to give decisive solutions to these problems, but his suggestions do cast much light on many details.

Not all of Schauer's theory is convincing. I doubt that his account of rights can be exended to human rights or moral rights, I also wonder whether there is more unity than he suggests behind the variety of arguments he discusses, and, if not whether the right to free speech is better seen as a group of distinct rights. In spite of such minor worries, those who want to learn about free speech could hardly do better than to read Schauer's book.

Dr. Sinnott-Armstrong is an assistant professorin the Colleges Department of Philosophy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe View from the Women's Locker Room

June 1983 By Agnes Kurtz -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

June 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

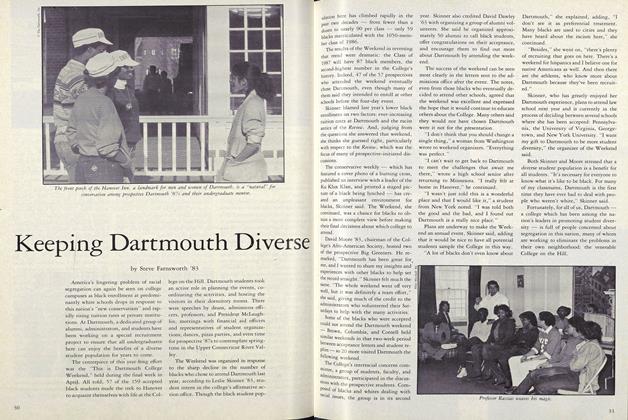

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

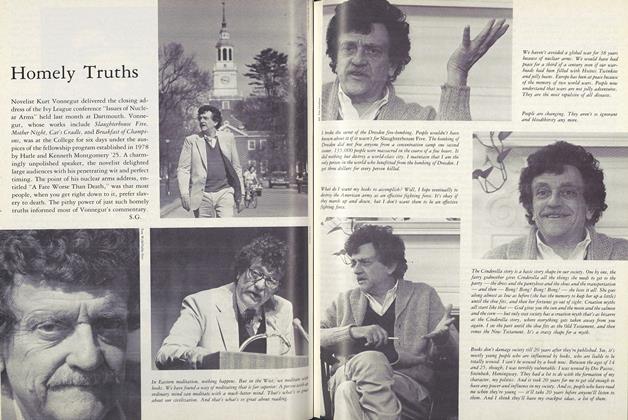

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G.

Walter Sinnott-Armstrong

Books

-

Books

BooksJohn C. Varney. '09 is the author of "First Wounds, A story in Five Chapters of Verse" published

June, 1926 -

Books

BooksOMAN SINCE 1856, DISRUPTIVE MODERNIZATION IN A TRADITIONAL ARAB SOCIETY.

DECEMBER 1967 By CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II -

Books

BooksThe Crookshaven Murder

MARCH, 1928 By F. L. C. -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN ITALY.

May 1953 By George C. Wood -

Books

BooksTHE BOOK OF AMERICAN CLOCKS

February 1951 By Harold G. Rugg '06 -

Books

BooksTHE MARKET FOR COLLEGE-TRAINED MANPOWER: A STUDY IN THE ECONOMICS OF CAREER CHOICE.

JANUARY 1972 By MARTIN SEGAL