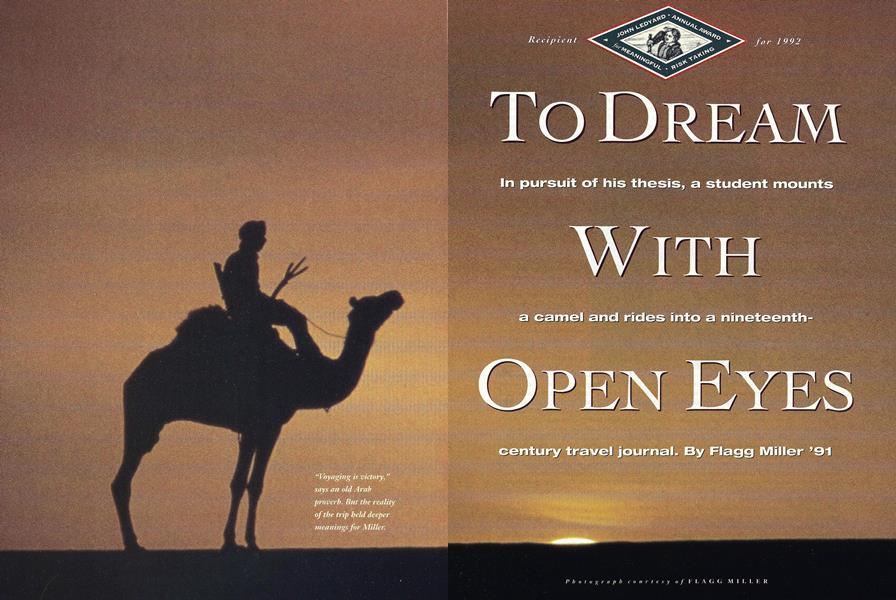

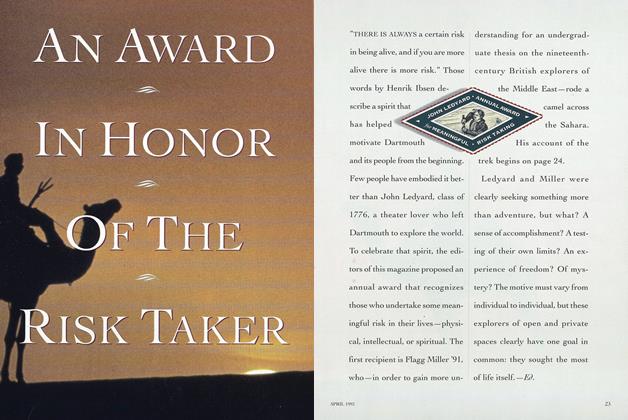

In pursuit of his thesis, a student mounts a camel and rides into a nineteenth- century travel journal.

THE GLINT OF THE STEEL BLADE flashed in the air. I stood frozen on a hot desert plain, staring as the sword swayed before me, wielded by a furious Bedouin. "Prepare to die!" he shrieked, shattering the stillness. My eyes darted to my companion, who was equally paralyzed.

"Well..." my friend said at last. "Give him the camel."

Helpless, I handed the Bedouin the reins to my mount. He sheathed his weapon and sprang into my saddle in almost one motion. He and the camel gradually vanished into the horizon's infernal glare. For the first time in 40 days of desert travel, I felt the heat of the Saharan sun reaching dangerous proportions. We were bereft of not just my camel but also our guide.

He was the one who took the camel.

A trip through the Sahara had long been a dream for me. Now it was a bad dream, but for years I had imagined myself in the sandy wastes, under the gigantic sun, with sinewy camel and gaunt-framed Bedouin. For my senior year at Dartmouth I had been working on a thesis on British explorers of the Middle Eastern deserts- Sir Richard F. Burton, Lawrence of Arabia—when I decided that a true understanding of the desert could come only by setting aside the thinking cap and putting on the turban. What exactly did Burton mean when he said that the desert was "a wild land inhabited by wilder men"?

A friend from San Diego, Bill Wheeler, had been planning a trip to the Sahara for years. Hoping to join him, I submitted a proposal to Dartmouth's center for international study, the Dickey Endowment. With its help, I soon found myself bound for Niger, about to step into the pages of my own travel journal.

Our point of departure was a century-old marketplace for caravans on the fringe of the Sahara. The bazaar is in the village of Agadez, inhabited by Tuareg men wearing dark robes, tasselled leather purses, enormous turbans, and long swords sheathed in oiled scabbards. Here were the descendents of a noble and fierce race of desert survivors, a Bedouin people whose dominions once stretched from Morocco to Chad. Having survived for centuries by braving the Sahara wilds, the Tuareg made their living by escorting treasureladen caravans for an exorbitant fee, or by ambushing them in the middle of the desert and leaving their victims to die of thirst. Although their way of life had been all but destroyed by modernization, their rugged spirit of self-dependence immediately won my respect, and I imagined myself identifying with them. And yet, as they walked around the busding medina, often arm in arm, now deep in counsel and now haggling furiously for camels and supplies, Bill and I got the feeling that we were utterly clueless.

Much of our uneasiness stemmed from the seemingly opaque languages hurled at us. While some of the Tuareg spoke Arabic—the rudiments of which I had picked up at Dartmouth—and occasionally French, most communicated in their own complicated tongue called Tamashek. I was often reduced to sign language and sheepish grinning. Moreover, our attempts to accomplish even the smallest task meant haggling with the inevitable band of curious and often heckling onlookers, some offering genuine assistance and others trying only to swindle us.

This babble was frustrating; we had so much to do before leaving on our trek. While we had brought canned foods and essential camping equipment from overseas, we needed to obtain the proper permits for travelling, find out what camel trappings were necessary and how to obtain them, purchase the endless variety of ropes, bags, containers, sleeping blankets, robes and turbans, and foodstuffs necessary for 40 days in the desert, and, most important of all, locate a reliable Bedouin guide and somehow buy four camels. Each task seemed to stretch itself out uncompromisingly over the long African days. As we discovered, the surest way to achieve travel capacity was to be self-sufficient, and so we made an effort to learn from the Bedouin how to tan our own leather, sew together camel harnesses, and make reliable burlap saddle bags.

Some things were best accomplished by the locals, however, and buying camels was one of them. First, we sent out word that we were looking for a guide, and after days of scoping and haggling with a variety of weather-beaten volunteers we placed our hopes in a young Tuareg named Balal. His agile stride and quiet, steady eyes spoke of much experience. To avoid our being rooked at the camel market, Balal would do our purchasing. Over the next week, Bill and I hovered discreedy behind the straw huts and tents on the outskirts of the market, eyeing the camels through our veiled turbans, communicating from afar by sign language, meeting secretly with Balal in dark straw huts, and venturing into the market only disguised as innocent, camera-clicking tourists rather than the shrewd prospectors we thought we were. At last we bought four majestic male camels, three for riding and one for water and baggage.

Who exactly fooled whom we will never know. As the week drew on, the locals began to conjecture about our mysterious creepings and purchases, and we were greatly chagrined to hear with increasing regularity the dreaded phrase screamed our way: "Oil est le chameau?" At least among some circles, the gig was definitely up.

It was with tremendous relief that we finally walked out of town after nearly two weeks in Agadez. How true the Arab proverb "Voyaging is victory!" We were at last on the high plains of Niger, bound for the Sahara. We travelled five to seven hours a day, stopping for several hours during midday to allow the camels to graze on whatever scrub they could find, and rest. The landscape during the first several weeks looked much like the American Southwest: vast plains of hard-packed earth, scattered vegetation, and huge mesas of rock. It was the frontier I had always imagined. Wells could be found every two or three days, and with the wells Tuareg, and animals. Gazelle, antelope, mountain goats, and ostriches could be seen occasionally from afar, and we even spotted the tracks of a leopard. Our greatest worry, however, was of encountering the notorious Al-Khasan, a brigand who was said to survive in the surrounding mountains by ambushing and robbing travellers. Whether by the hand of Al-Khasan or of another vagabond, several French tourists in Land Rovers were robbed and killed later that month. Guarding our camels at night with particular care, however, we passed through his territory unassaulted.

Mornings began early. I generally woke before dawn, my eyes and mouth covered with a layer of gritty sand, and wriggled out of my sleeping bag into the chilly night air. Warmth would come only with the first direct rays of the sun, and then too quickly for comfort. The first order of the day: find the camels. Left to graze at night, unleashed but hobbled, they would wander across the barren plains in search of food, sometimes shuffling five or six miles under the moonlight if pasturage was sparse. Knowing that they inevitably dashed for home, even if thousands of kilometers away, I could usually start off in the right direction, but it was crucial to locate their footprints and follow. Fine sand left excellent imprints, making my job easier, but hard-packed flint and, worst of all, volcanic rock made tracking a meticulous and exhausting chore. In such conditions I had to rely on the smallest clues, from overturned rocks to small droppings, and filled in the gaps with guesswork. Some days the camels simply could not be found, and our guide had to use his greatest powers of deduction to locate the fleeing animals and bring them home. Usually, however, after two or three hours' search I would overtake them in mid-flight, thread my lead-ropes through their nose rings, and lead them back to camp, where I would devour a breakfast of oats and coffee and then pack to travel.

After several weeks and several hundred miles, we noticed the rocky valley floors turning to sand, and the wells growing farther apart. We were entering the great Ten ere Desert, a sea of dunes indicated by an immense blank space covering the top quarter of our map of Niger. Huge mountains of sand, some 900 meters high, now replaced the rock buttes we had seen before. We felt dwarfed by the moonscape around us, dominated by the graceful curves of dune stretching to the sky. The services of our guide now proved essential, as he navigated through confusing patterns of crests and troughs, and during one bad sandstorm we congratulated ourselves on having brought our compass. Getting lost in the Sahara seemed much too easy, and the consequences lethal. Climbing the dunes with our camels and then descending all day under the silent but brutal heat of the sun fractured the mind and body

Every few days we would cross paths with a Bedouin transporting worldly goods by foot or by camel, and after an exhausting series of repeated handshakes, nodding, and verbal parlaying we would inquire about directions, grazing, and, most important, reliable sources of water. By and large, the reports were accurate, but on several occasions wells that were said to be dependable had run dry, forcing us to make good time to the next potential well. At times like these the desert seemed disturbingly silent, lonely, and merciless. Fortunately, however, we never experienced its total wrath, for we somehow managed, out of the hundreds of dry miles around us, to locate a meter-wide sunken shaft when we most needed it.

Arrival at the wells proved to be the most festive part of the trip. Bedouins, having finished treks of their own across the sands, would cluster with their families and animals around an impressive hole in the sand that would reach down to a deep, stagnant pool far below. The mouth of the well would writhe with the sinewy bodies of women and men who strained under the weight of the waterskin hauled up from the darkness. The water would finally emerge into the light with a quenching, musical splash amid high-pitched whoops of joy and rhythmic clapping. Parched camels, goats, and donkeys would jockey for position before the water troughs, biting, kicking, roaring, their eyes fall of wild excitement, clouds of dust rising from their feet.

We had been travelling for five weeks, gradu- ally making our life on the road more efficient and enjoyable, when relations with Balal began to sour. He had become more lethargic, and complained constantly about his daily wage. Bill and I thought we could deal with him, but things got progressively worse. Toward the end of the trip he announced that we did not have the proper papers for some of the areas we had travelled through, and could be in major trouble if the police found out. He spoke of our camels being impounded, our film being exposed, jail sentences, and general mistreatment by "very, very cruel gendarmes." Bill and I had checked every possible military outpost for necessary travel permits before leaving and had concluded that we were abiding by the rules, but Balal's insistence greatly worried us. Days were spent in deep consternation and paranoia. At the same time, Balal began questioning us about our camels: Would we sell them to him? For how little? Would we perhaps give him one as a bonus at the end of the trip? It was only on the last day of our journey that his method became fully and horribly apparent. Stopping us in the middle of a vast plain, he coldly explained that we could either give him a camel—or he would deliver us into the hands of the infamous police with a host of trumped-up charges and leave with his pay. Bill and I refused such blackmail, and moments later he unsheathed his sword.

We finished the trip in a great outpouring of nervous energy, mad bargaining, and high excitement. We managed to make it into Axlit, our destination. Over the next three days we thrashed out the details of the incident and of our entire trek with the police, and with our guide, who surprised us by showing up. We discovered that no permit had been necessary, we had crossed no illegal boundaries, and our guide had indeed been blackmailing us. It was ultimately decided, according to the age-old traditions of the Tuareg, that since no real harm had been done, and Balal had been our guide, that he would go free with full wages, sans camel, and we could also go free—but only upon paying everything Balal had asked for. Handing over our money that final day, our camels having been sold at market for half the price we paid, I marveled that I was not alone in being the snookered Westerner, and I could only laugh. My whole trek in the desert—from the moments of frustration and alienation to those of tremendous elation—had to be considered in its entirety. I had come to the Sahara, like T. E. Lawrence, in order to "dream with open eyes," and had learned that part of the wild thrill of adventure lay in struggling with an uncomfortable reality that did not often get translated in the travel journals I had read. The desert, I discovered, could be both a hospitable and a hostile place, depending on the moment, and, more importantly, my attitude. The shifting pattern of the arabesque dune had taught me much, and yet subtly revealed how much more I could learn. an

Flagg Miller '91

"I STAREDas the swordswayedbefore me.'Prepare todie!' heshrieked,shatteringthe stillness."

"WE HAD crossed noillegalboundaries,and ourguide hadindeedbeen blackmailing us."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

April 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

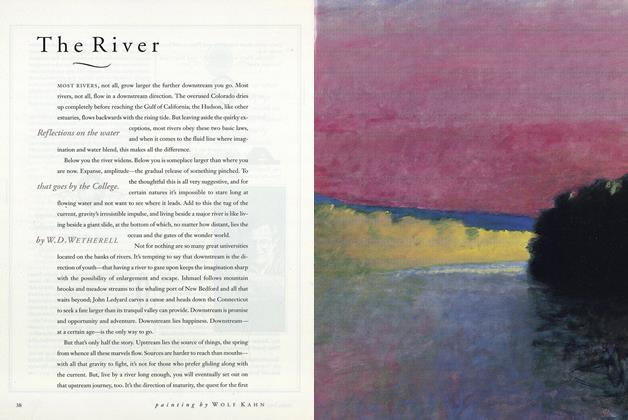

FeatureThe River

April 1992 By W. D. Wetherell -

Feature

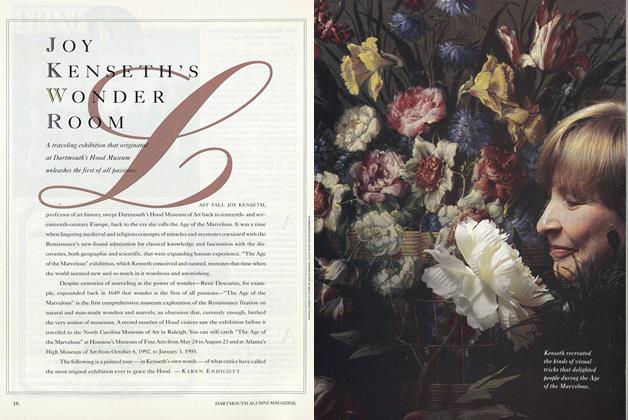

FeatureJoy Kenseth's Wonder Room

April 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

April 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe Imagination Unbound

April 1992 By Ulrike Rainer -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

Features

-

Feature

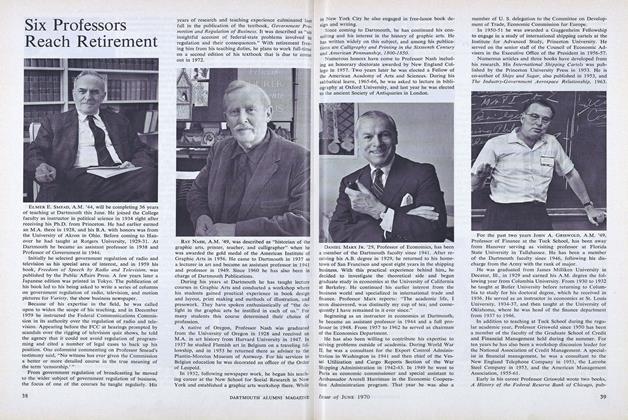

FeatureSix Professors Reach Retirement

JUNE 1970 -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

MAY 1996 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Alumni College August 15-26, 1971

JANUARY 1971 By A.T.G. -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

DECEMBER 1983 By Howard A. Vernon