FIVE years ago, when the Dartmouth Trustees decided that the College's approaching bicentennial should be marked by a broadly planned and strenuous pursuit of excellence on all fronts, one of the first areas designated for study was that of the associated schools. From one part of the study came a new program of engineering education, inaugurated in the fall of 1958; and there is now in process of realization a new and expanded pattern of medical education that amounts to a virtual "refounding" of Dartmouth Medical School.

When the reappraisal of the Medical School began, some basic questions had to be faced. Was it desirable or feasible to think of returning to the status of a four-year school, such as Dartmouth Medical School had been from its founding in 1797 until 1914? As a two-year, basic science school, such as it has been for the past 45 years, does the School have a future? Is it making a worthwhile contribution to medical education in the United States and to the country's growing need for doctors? Is there a mutually advantageous relationship with the College proper, which in recent years has been devoting approximately $150,000 annually from general funds to support the Medical School?

To help answer the central question about the future of the Medical School, the Trustees enlisted the cooperation of a number of outside authorities in medical education. Among those who contributed to the study were the late Dr. Alan H. Gregg, director of medical sciences for the Rockefeller Foundation; Dr. George Packer Berry, dean of Harvard Medical School; Dr. Robert F. Loeb, Samuel Bard Professor of Medicine at Columbia University; Dr. W. Barry Wood, vice president of The Johns Hopkins University; and Dr. Waltman Walters '17, Professor of Surgery at the Mayo Clinic. After two years of study, it was firmly concluded that Dartmouth Medical School

can continue to make a distinctive contribution to medical education, and that far from changing its present plan of offering only the first two years of the medical course, the School should develop and perfect this to the point where it can serve as a much-needed prototype for alleviating some of the critical problems now being faced in American medical education.

These critical problems center on America's need for more doctors. With a tremendous population growth in the offing, and medical service being increasingly used, it is estimated that by 1975 our medical school will have to graduate 11,000 new physicians every year, compared with the present 7,400, just to maintain the current physician-patient ratio. The U. S. Surgeon General's Consultant Group on Medical Education in its very recent report, "Physicians for a Growing America," recommends a three-part answer to the problem: (1) increased enrollment in existing medical schools; (2) establishment of new four-year medical schools; and (3) establishment of two-year programs in the basic medical sciences which will permit students to transfer to the four-year schools for the final two years of clinical study. Part 3 of this recommendation had been anticipated in the report submitted to the Dartmouth Trustees about two years ago.

The two-year school has the distinct advantages of avoiding the staggering cost of establishing a new four-year school (estimated at $40,000,000 or more), of being able to shorten the full medical course by one year by admitting students in the senior year of undergraduate college, and of having students ready to transfer into the third year of a four-year school, which is exactly the level at which the four-year school has empty places to fill. Because of the normal attrition during the first two years, the four-year schools find themselves with an estimated 700 to 800 vacancies in the third year.

At the end of World War II there were only eight two-year medical schools in the country. Four have since become four-year schools and one other is in the process of becoming so. By its current endeavor to strengthen and develop its two-year program and to serve as a model for the sort of school that can provide part of the answer to the national medical problem, Dartmouth Medical School is greatly enhancing its already distinctive place in the overall structure of American medical education.

That the School has this opportunity, as well as an equally important opportunity to produce men interested in medical teaching and investigation, was a major conclusion of the study authorized by the Dartmouth Trustees. Flowing from this were recommendations, in the 1957 report, that the Medical School strengthen its educational program anchored in the basic medical sciences, double its enrollment from 48 to 96 students, and raise the capital funds needed to enlarge the full-time faculty and build an entirely new plant to replace the ancient buildings that are literally used up.

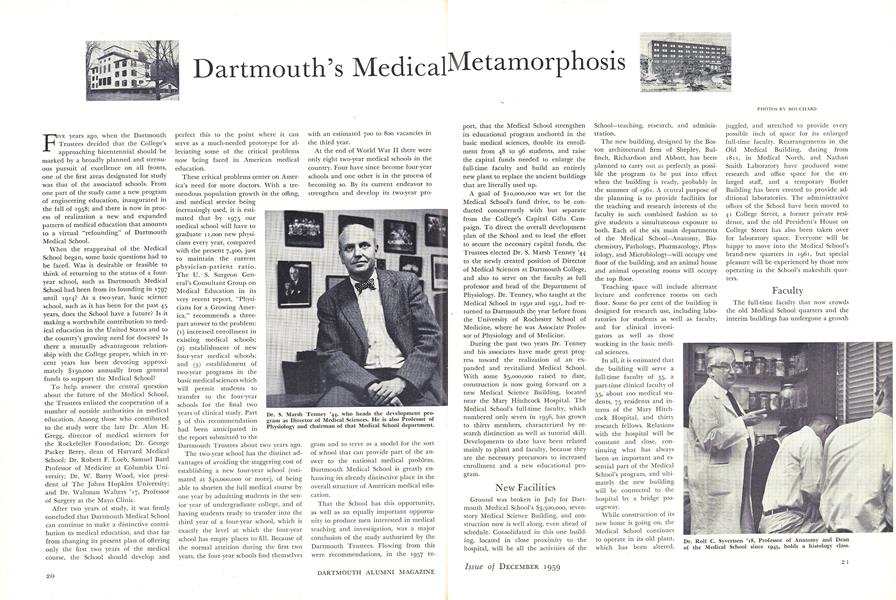

A goal of $10,000,000 was set for the Medical School's fund drive, to be conducted concurrently with but separate from the College's Capital Gifts Campaign. To direct the overall development plan of the School and to lead the effort to secure the necessary capital funds, the Trustees elected Dr. S. Marsh Tenney '44 to the newly created position of Director of Medical Sciences at Dartmouth College, and also to serve on the faculty as full professor and head of the Department of Physiology. Dr. Tenney, who taught at the Medical School in 1950 and 1951, had returned to Dartmouth the year before from the University of Rochester School of Medicine, where he was Associate Professor of Physiology and of Medicine.

During the past two years Dr. Tenney and his associates have made great progress toward the realization of an expanded and revitalized Medical School. With some $5,000,000 raised to date, construction is now going forward on a new Medical Science Building, located near the Mary Hitchcock Hospital. The Medical School's full-time faculty, which numbered only seven in 1956, has grown to thirty members, characterized by research distinction as well as tutorial skill. Developments to date have been related mainly to plant and faculty, because they are the necessary precursors to increased enrollment and a new educational program.

New Facilities

Ground was broken in July for Dartmouth Medical School's $3,500,000, sevenstory Medical Science Building, and construction now is well along, even ahead of schedule. Consolidated in this one building, located in close proximity to the hospital, will be all the activities of the School—teaching, research, and administration.

The new building, designed by the Boston architectural firm of Shepley, Buifinch, Richardson and Abbott, has been planned to carry out as perfectly as possible the program to be put into effect when the building is ready, probably in the summer of 1961. A central purpose of the planning is to provide facilities for the teaching and research interests of the faculty in such combined fashion as to give students a simultaneous exposure to both. Each of the six main departments of the Medical School—Anatomy, Biochemistry, Pathology, Pharmacology, Physiology, and Microbiology—will occupy one floor of the building, and an animal house and animal operating rooms will occupy the top floor.

Teaching space will include alternate lecture and conference rooms on each floor. Some 60 per cent of the building is designed for research use, including laboratories for students as well as faculty, and for clinical investigators as well as those working in the basic medical sciences.

In all, it is estimated that the building will serve a full-time faculty of 35, a part-time clinical faculty of 55, about 100 medical students, 75 residents and interns of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital, and thirty research fellows. Relations with the hospital will be constant and close, continuing what has always been an important and essential part of the Medical School's program, and ultimately the new building will be connected to the hospital by a bridge passageway.

While construction of its new home is going on, the Medical School continues to operate in its old plant, which has been altered, juggled, and stretched to provide every possible inch of space for its enlarged full-time faculty. Rearrangements in the Old Medical Building, dating from 1811, in Medical North, and Nathan Smith Laboratory have produced some research and office space for the enlarged staff, and a temporary Butler Building has been erected to provide additional laboratories. The administrative offices of the School have been moved to 41 College Street, a former private residence, and the old President's House on College Street has also been taken over for laboratory space. Everyone will be happy to move into the Medical School's brand-new quarters in 1961, but special pleasure will be experienced by those now operating in the School's makeshift quarters.

Faculty

The full-time faculty that now crowds the old Medical School quarters and the interim buildings has undergone a growth that is spectacular when compared with the full-time staff of just a few years ago. The faculty had long been staffed with only one full-time professor in each of the preclinical fields covered in the two-year course, but it also had a strong teaching resource in the part-time instruction given by more than fifty doctors making up the staffs of the Hitchcock Clinic and the Mary Hitchcock Hospital. This parttime clinical faculty will continue to play a vitally important part in the Medical School's new educational program, giving Dartmouth's medical students an unusual opportunity to experience some clinical application of their studies in the first two years.

New appointments to the faculty in the past three years have all contributed to the aim of enlarging, strengthening, and adding depth to the full-time staff teaching the basic medical sciences, which the School's revamped curriculum will emphasize. This staff now numbers thirty men and women, but its size needs to be explained by the fact that a number of its members are term appointees supported by outside research grants.

New appointments to the medical faculty since 1957 have been most numerous in the Departments of Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pharmacology. More recently this academic strengthening has been extended to Cytology, and further development is planned for Microbiology and Pathology.

The caliber of the medical faculty being recruited at Dartmouth is exemplified by the four new professors now heading departments of the School. Dr. Tenney, who doubles as the School's administrative head and as Professor of Physiology, has been a Markle Scholar in the Medical Sciences since 1954. He took his M.D. at Cornell and was formerly an associate professor at the University of Rochester Medical School, which he left in 1956 to come to Dartmouth. He is carrying on important research on the physiology of circulation and respiration, supported by grants from the National Heart Institute; and for the National Science Foundation he is engaged in studies related to respiration at high altitudes.

Dr. Manuel Morales, chairman of the Biochemistry Department since 1957, came to Dartmouth from the Naval Medical Research Institute in Bethesda, Md., where he was Chief of the Division of Physical Biochemistry. He took his Ph.D. degree at the University of California in 1942, and was assistant professor at the Institute of Biophysics, University of Chicago, before joining the Naval research unit. His work at the latter institute won him a national reputation in his field.

Dr. Robert E. Gosselin, head of the Department of Pharmacology, took his Ph.D. and M.D. degrees at the University of Rochester, where he later served as assistant professor, 1954-56. He was a scientist with the Rochester Atomic Energy Project, served two years with the U. S. Army Chemical Center, and presently is civilian consultant to the Army Chemical Corps. He is co-author of an authoritative book on household poisons, and serves as director of the Poison Information Center at the Mary Hitchcock Hospital.

Dr. Shinya Inoue, head of the Department of Cytology, was educated at Tokyo University and at Princeton where he received his Ph.D. He has taught at the University of Washington, Tokyo Metropolitan University, and Rochester. In 1955 he was a Scholar of the American Cancer Society. In collaboration with Dr. Lewis Hyde of the American Optical Company, Dr. Inoue has developed a powerful new research tool, a polarizing microscope twenty times more sensitive than previous devices, permitting the study of living cells and, for the first time, the photographing of muscle fiber fine structure.

A prime characteristic of the whole new medical faculty is its combination of research and teaching abilities. Taken in its entirety, the School's program of research in the basic medical sciences is by all odds the most impressive body of investigative work now being done at Dartmouth. Research and training grants total approximately $600,000 for the current year and are financing nearly forty different research projects, including studies dealing with heart and lung disease, the mechanism of cancerous growth, the causes of anemia and leukemia, the chemical changes responsible for rhythmic functions in single cells, and the elements that produce high blood pressure.

In support of the investigative work of the basic-science faculty, the Medical School is receiving grants from such national organizations as the U. S. Public Health Service, the National Science Foundation, the American Heart Association, the American Cancer Society, the Research Corporation, and the American Trudeau Society. Additional support from state organizations comes from the Spaulding Trust and the New Hampshire heart and cancer societies.

Until about three years ago the Medical School itself had received no outside grants for basic research. Investigation was almost entirely confined to the clinical field and was being done through the agency of the Hitchcock Foundation, which pioneered in research related to the Medical School and now has merged its program with that of the School.

One striking example of the great change in the Medical School's investigative activity is the recent three-year grant of $230,000 from the Science Foundation to enable Dr. Inoue, in cytology, to carry out his study of the fine sttucture of living cells. With a staff of six, including his colleague Dr. Wayne Thornburg, who came from the University of Illinois this year, Dr. Inoue is investigating one of the fundamental problems of modern biology - the nature of cellular function. A substantial part of the grant will be used to provide two research instruments designed by Drs. Inoue and Thornburg. One is a high-resolution polarizing microscope, developed by Dr. Inoue to study the submicroscopic structure of living cells, and the other is an ultra-sensitive microspectrophotometer, invented by Dr. Thorn-burg to analyze the spectral characteristics of microscopic objects.

In all the other departments of the Medical School important research is being carried on. In Biochemistry, whose members have come to Dartmouth mainly from the Naval Medical Research Institute, Dr. Morales and seven associates are working on projects having to do with the physical chemistry responsible for contraction of muscle, and on other projects dealing with protein structure and function. The Physiology Department, with a staff of ten, has a major interest in heart and lung research, but is also conducting important work on nerve function and the physiology of endocrine glands. Other heart research is being done in the Department of Pharmacology. Dr. Gosselin, its chairman, in collaboration with Visiting Professor Jane Sands Robb, from the State University of New York, is interested in the rhythm function of cells, including those of the heart. In the Department of Pathology, Dr. Fairfield Goodale, who came from Harvard Medical School last year, is making investigative studies of the pathogenesis of fever; and Dr. Franklin G. Ebaugh '44 is doing research on leukemia and the causes of bone marrow failure.

Curriculum

The revised educational program to be put into effect by Dartmouth Medical School will, in essence, be a continuation of the two-year course that over the years has so thoroughly prepared students for subsequent clinical training in four-year medical schools, and it will still embody Dartmouth's traditional combination of a liberal arts education with specialization in the medical sciences. But this essential plan will be carried out in new and imaginative ways, and it will include several innovations that are perhaps unique in American medical education. In the field of the two-year schools, certainly, Dartmouth Medical School will offer a program of such excellence and vitality that it is bound to have wide influence and also become, hopefully, a model for two-year medical programs elsewhere.

Dartmouth undergraduates admitted to the Medical School will begin their studies, as they do now, at the end of the junior year. With a doubled enrollment, however, the School plans to break away from its all-Dartmouth student body and admit men who have qualified with three or four years of liberal arts and premedical education at other accredited institutions. Admission standards will be high, and the student body will be of outstanding quality.

The two-year course of study will concentrate on the basic medical sciences, taught with functional emphasis in which medicine is conceived to be part of the broader discipline of biology. The curriculum is being planned as a logical extension of the life sciences studied in a liberal arts curriculum, although a strong orientation toward the practice of medicine will be provided by the School's clinical faculty and its close relationship with the excellent 300-bed teaching hospital in the Mary Hitchcock Hospital. By the end of his second year the medical student will have had comprehensive courses in anatomy, histology, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, pathology, microbiology, physical diagnosis, and the nervous system, plus a correlation seminar combining many of these disciplines.

One striking innovation in the Medical School's new educational plan is a flexibility that will permit the student to make a choice, at any point, of becoming a practicing physician or of continuing with the basic sciences and becoming a medical teacher or investigator. Even greater than the nation's shortage of doctors is the shortage of medical teachers and researchers, and Dartmouth Medical School believes that one of the strong features of its pilot program is the promise it contains for helping to meet this need as well as that of more physicians. As the program develops, it is expected that the School will offer graduate work leading to the Ph.D. degree in the basic medical sciences. This opportunity definitely is open with the type of faculty the School is recruiting.

The greatest innovation in the curriculum will be an experiment in medical education involving six months of elective research for certain outstanding students. The students permitted to undertake this work with tutorial guidance will be those who perform with distinction in the basic sciences and demonstrate marked ability in deductive reasoning, imagination, and experimental precision. Each student so selected will participate intimately in the research project of a tutor, who may be from the science faculty of the College as well as from the Medical School faculty.

The elective research project will be a full-time one beginning in the winter term of the first year and continuing for one term in the second year. The extra time required will be gained by eliminating the first summer vacation and having the student begin medical school in late June. The second summer vacation will be an additional elective period for second-year students.

For the students not engaged in these investigative projects the research periods will be used for concentrated study in a given field. Here again the advantages of a tutorial system will come into play, only the student will be guided in intensive reading and study rather than in laboratory research. The object in either case will be the greatest possible development of the student's individual interest and motivation. Even those students who do not elect or qualify for special research projects will engage in a certain amount of investigative study during the two-year course, in order that they may gain some first-hand appreciation of this important aspect of modern medicine. Attention to the psychological side of medicine will not be neglected, and one of the latest appointments to the Medical School faculty is that of Dr. Robert J. Weiss of Columbia University as Professor of Psychiatry.

The educational program planned for the Medical School and the caliber and interests of the science faculty associated with it forecast a stimulating influence upon the science departments of the undergraduate College. And in the other direction, the liberal arts and cultural climate of the College, not to mention its own strengthened work in the basic sciences, will give the Medical School an enriching context within which to carry on its work. In the opinion of the Trustees' study group, this two-way gain clearly answers the question whether there is a mutually advantageous relationship between the Medical School and the parent College.

To the fullest extent possible, through the raising of new capital funds and through research and training grants, Dartmouth Medical School aims to finance its own way as it expands and puts into effect its new educational program. Of the $10,000,000 being sought by the School, approximately half will be used for construction and maintenance of the Medical Science Building and the other half for endowment of faculty salaries. The achievement of one-half of its fund goal has been made possible by major gifts from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Commonwealth Fund, the U. S. Public Health Service, the Ford Foundation, the James Foundation, the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, the John and Mary R. Markle Foundation, and the Spaulding Trusts, combined with many more gifts and pledges made by Medical School alumni, corporations and organizations. With the College's own Capital Gifts Campaign successfully concluded, the Dartmouth Development Office is now assuming direction of a more intensive effort to raise the balance of the needed funds. As it has been up to now, the campaign will be conducted among those foundations, corporations and individuals - doctors and non-doctors, alumni and non-alumni - who are believed to have an interest in the exciting future of Dartmouth Medical School.

Dr. S. Marsh Tenney '44, who heads the development pro- gram as Director of Medical Sciences. He is also Professor of Physiology and chairman of that Medical School department.

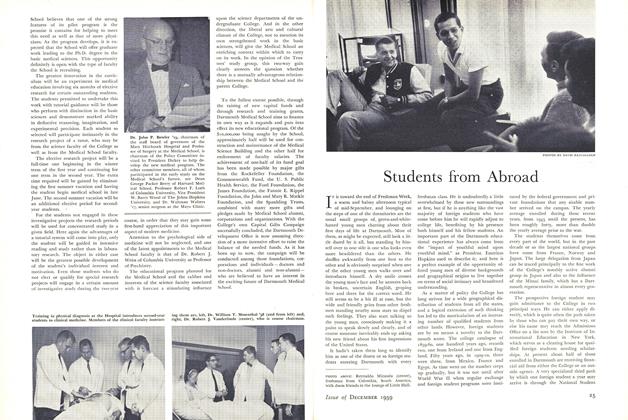

Dr. Rolf C. Syvertsen '18, Professor of Anatomy and Dean of the Medical School since 1945, holds a histology class.

Dr. Manuel Morales, Biochemistry chairman,is directing research on muscle contraction.

Dr. Shinya Inoue, Cytology chairman, has alarge grant for the study of living cells.

Dr. Robert E. Gosselin, Pharmacology chairman, is adviser to the Army Chemical Corps.

Dr. Fairfield Goodale, in Pathology, is doing research on the pathogenesis of fever.

Dr. John P. Bowler '15, chairman of the staff board of governors of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital and Professor of Surgery at the Medical School, is chairman of the Policy Committee invited by President Dickey to help develop the new medical program. The other committee members, all of whom participated in the early study on the Medical School's future, are Dean George Packer Berry of Harvard Medical School, Professor Robert F. Loeb of Columbia University, Vice President W. Barry Wood of The Johns Hopkins University, and Dr. Waltman Walters '17, senior surgeon at the Mayo Clinic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudents from Abroad

December 1959 By J.B.F. -

Feature

FeatureMary Baker Eddy and Dartmouth

December 1959 By JOHN B. STARR '61 -

Feature

FeatureSTEFANSSON

December 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

December 1959 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

December 1959 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, WALDON B. HERSEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

JUNE 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's 214th

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Doug Greenwood -

Feature

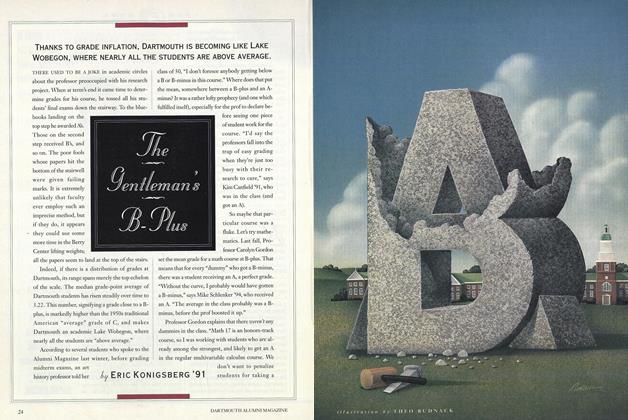

FeatureThe Gentleman's B-Plus

February 1992 By Eric Konigsberg '91 -

Feature

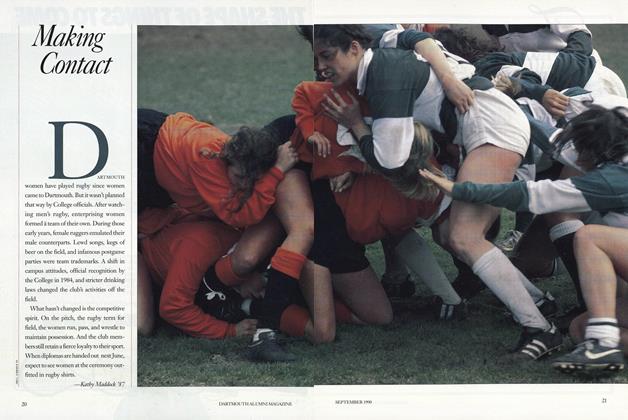

FeatureMaking Contact

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Feature

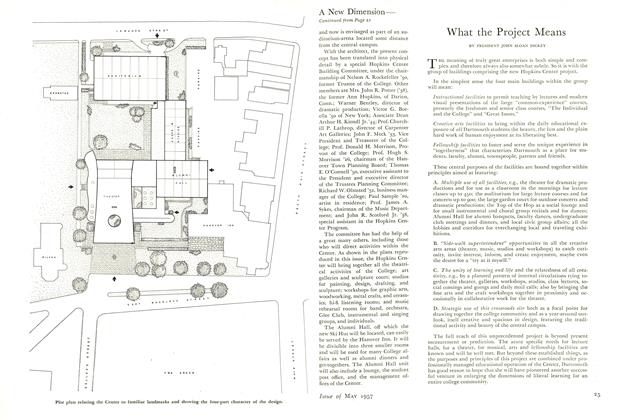

FeatureWhat the Project Means

MAY 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY