The World Salutes Dartmouth's Arctic Expert on His 80th Birthday

THERE is probably no name associated with Dartmouth College better known throughout the world than that of Vilhjalmur Stefansson. The College is honored through the name twice over, not only for the remarkable personality and historic figure that it represents, but for the great collection of books relating to polar regions which during a long life he has accumulated, and which are now part of the Dartmouth College Library.

I first met Stef when I was an undergraduate, just back from a geological expedition into an unexplored part of northern Canada. On return I was anxious to learn much more about those far places. With growing fascination in what I found to read in the Stefansson Collection, I spent much of my free time there. Stef's position in the Collection is not only that of steadiest user but, also, that of the quickest and most infallible source of information. Although the writing of a steady flow of books and articles and a flood of correspondence fill his 12-hour working day, he is always ready to answer questions on any aspect of the polar regions. His extemporaneous lecture on whatever the difficulty may involve could be published verbatim and his conclusion, complete with a critical bibliography, includes just about everything there is to be said about the matter, for and against. Many students, whose interest in the north was at first only general, have been stimulated by this direct and warm encouragement to take a personal, continuing and specialized concern in northern problems.

But this was not how Stef himself became interested in the north. Born of Icelandic parents in Manitoba, he was brought up on the Dakota prairies. After experience as a cowboy, he entered the University of North Dakota. There his exuberant spirit brought him into conflict with the administration and he was expelled. Soon after he entered the University of lowa, as a freshman again, but graduated at the end of a single year there by the simple expedient of passing final examinations in four years' worth of subjects whenever he felt ready to take one of them. Offered a theological scholarship, he first studied divinity at Harvard, but changed to anthropology. His regional interest in this subject was east central Africa. Shortly before leaving for Africa, however, he accepted a position as ethnologist with the Leffingwell-Mikkelsen Expedition which was intended to work in the western Canadian Arctic. The expedition proper went by ship from British Columbia north through the Pacific; but Stef elected to travel overland and down the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Sea, there to meet the rest. The expedition's ship got itself icebound before reaching him, leaving him provided for an Arctic winter with little more than the clothes he stood in and a thorough knowledge of the African anthropological literature.

Never one to waste an opportunity he moved in with a family of Eskimos (to the surprise and horror of his white acquaintances) and set about learning their language, habits, hunting and traveling techniques. He was forever lost to the African field from this time. The experiences of this trip, 1906-07, are delightfully told in Hunters of the Great North. He returned home by walking west from the Mackenzie delta across the Rocky Mountains, then by drifting on a raft down to Fort Yukon, Alaska, where he caught a river boat to Dawson City.

Once home he lost no time obtaining backing for another, more elaborate trip. Supported by the American Museum of Natural History and the Geological Survey of Canada, he was back in the Arctic in 1908 for a four-year stay. Traveling widely with Eskimos as an Eskimo, he was able to fill in or to correct considerable areas of the maps of the Canadian western Arctic. On this expedition he had a most extraordinary opportunity, the discovery of a group of some 700 Eskimos of whom about 500 had never before seen a white man. Plenty of explorers have found groups of primitive peoples, but probably none was at once a trained anthropologist, thoroughly familiar with his subjects philosophy and way of life, and at the same time able to converse perfectly with them from the first encounter. These exciting years are described in My Life with the Eskimo.

When Stef returned from this expedition, he found himself a famous man. Another larger expedition was organized and, since one of his objects was the discovery of new lands in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, this was supported by the Canadian Government. Stefansson's mode of travel was to support both men and dogs, whether on land or on ice, exclusively by hunting. Both Eskimos and Whites "knew" at this time that the farther north you went, on land or sea, the less game there was to be found. Seeing no real evidence to support this belief and a good deal to deny it, he staked his life on the opposite opinion and made a goday, 500-mile journey across the drifting ice pack north of Alaska to see if there might be islands there, where no ship had ever penetrated. The results were successful; enough game had everywhere been found to support the party comfortably; and, through deep-sea soundings and visually, there was now the negative certainty that in the large area covered by their journey no land would ever be found.

Later journeys north of Banks and Prince Patrick Islands resulted in the discovery of the last major land masses to be found in that region, very considerable corrections to the outlines of previously discovered islands, and the filling in of a number of coastal segments. All these long dog-sleds journeys were carried out with minimal equipment and an almost complete lack of cooperation from the majority of the expeditionary force, who thought that their commander's revolutionary ideas and plans, were little short of madness. During this period, he was a number of times reported dead, as he had remained away for periods far longer than the food he took with him could have lasted. The travels and memorable events of these years, 1913-18, are recorded in a classic of narrative adventure, The Friendly Arctic.

Ten winters and thirteen summers were the total of Stefansson's arctic experience. Although he contemplated more expeditions, he never found time for them in his later life as a scholar, lecturer and author. His new mission was to bring to the attention of the world the strategic position, the resources and the potentialities of the Arctic. This he did with a command of language and information which made him a foremost figure of the time, continuously in demand as a speaker and as an adviser. He traveled throughout the world describing the Arctic by the then unimaginable adjective "friendly.' Thoughtful men today allow that this was, among the very many, his greatest contribution—the removal of that fear which had for so long surrounded ideas about the Arctic. He had demonstrated by prolonged, personal example that by using proper knowledge and skill, men can deal advantageously in the Arctic (and, by extrapolation, in the Antarctic) with conditions which were otherwise forbidding.

It is impossible to list and to describe in a small space all the wide-ranging subjects that have received Stefansson's critical attention and been magnified by his thought. His is a vision which more than anything else sees the unity of knowledge, of the essential relations of geography and history. From this intellectual position, he has been able to make contributions not only to his first chosen field of anthropology, but also to the studies of physical, cultural and historical geography, of religion, of psychology, of linguistics, of medicine and nutrition, of history and of philosophy. Original thought is remarkable enough, but added to this Stef has a gift of lucid and imaginative expression which makes his works contributions to literature in their own right. Those who have not yet read any of this writing have a notable experience before them.

Stef has gathered over the years as a research tool a vast accumulation of polar books. Once the greatest polar library in the world, it is now exceeded in size by that of the Leningrad Arctic Institute, with which Mrs. Evelyn Stefansson, librarian of the Stefansson Collection, this summer arranged an exchange program. The Stefanssons's personal library was acquired for Dartmouth College in 1951 through their generosity and that of Mr. Albert Bradley '15. Since that time Dartmouth's interest in and contribution to polar matters has steadily grown.

It would be fitting indeed if the College which is honored by the presence of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and of his great library, should elaborate the unity of knowledge with a northward orientation that exists in his mind into an interdisciplinary program which would be as diversified but still single in its ability to include not only the problems of ordinary experience but those of the ends of the earth.

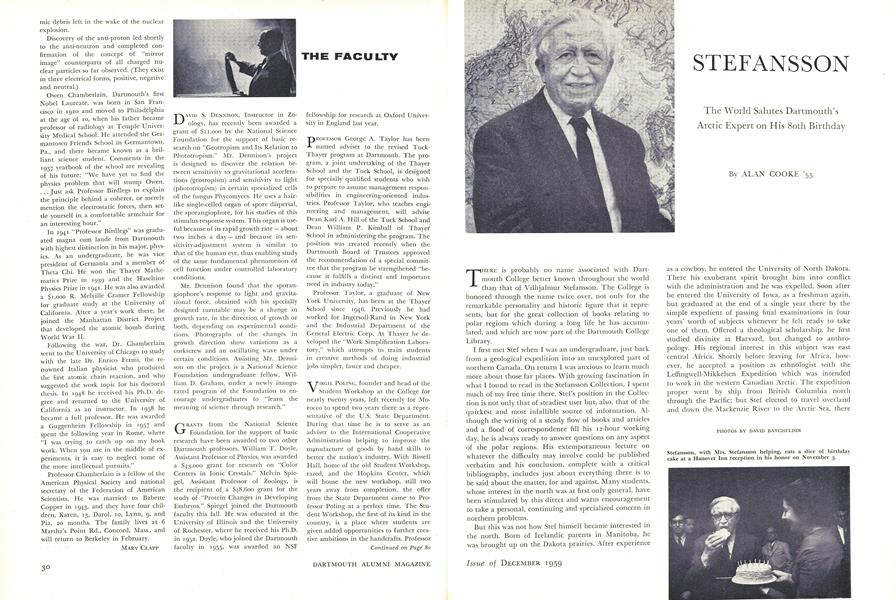

At his desk in Baker Library, Stefansson reads some of the 500 greetings that poured into Hanover from all over the world. Included were messages from the White House; Prime Minister Diefenbaker of Canada; Mikkelsen of Denmark, leader of the first arctic expedition Stefansson went on; Ambassador Thor Thors of Denmark; Governor Luis Marin of Puerto Rico; presidents of the American Geographic Society, National Geographic Society, and Geographical Society of Paris; Commander Finn Ronne and Dr. Paul Siple, antarctic expedition leaders; Commander Jim Calvert of the atomic submarine Skate; a party of 18 scientists now stationed at the South Pole; U. S. Senators and Congressmen; and many Dartmouth alumni who were students in Stefansson's arctic seminars.

Stefansson returns to the shelf one of the volumes in his famous collection on the polar regions, the finest of its kind in the western world and a boon to many visiting scholars.

Dr. Laurence Gould (r), president of Carleton College and director of the U. S. antarctic program for IGY, lectured at Dartmouth on November 3. Also on the program marking Stefansson's birthday was Trevor Lloyd (1) of McGill, former geography professor here.

Volume 1, Number 1 of a new Dartmouth publication "Polar Notes" is presented to Stefansson by Raymond Holden (left), editor of the first number, and Mrs. Stefansson, who wrote an article. Dedicated to the explorer, it had 80 pages to mark his birthday.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

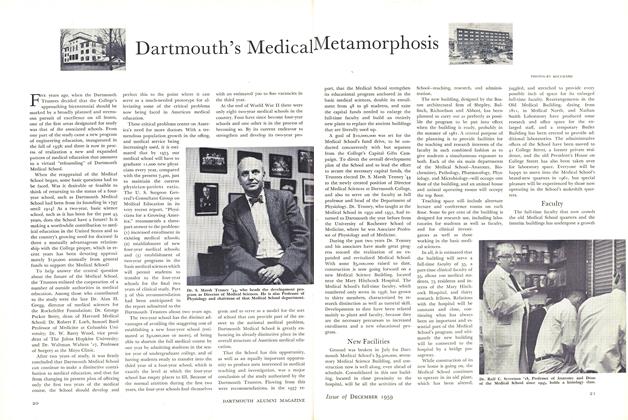

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Feature

FeatureStudents from Abroad

December 1959 By J.B.F. -

Feature

FeatureMary Baker Eddy and Dartmouth

December 1959 By JOHN B. STARR '61 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

December 1959 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

December 1959 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, WALDON B. HERSEY

ALAN COOKE '55

Features

-

Feature

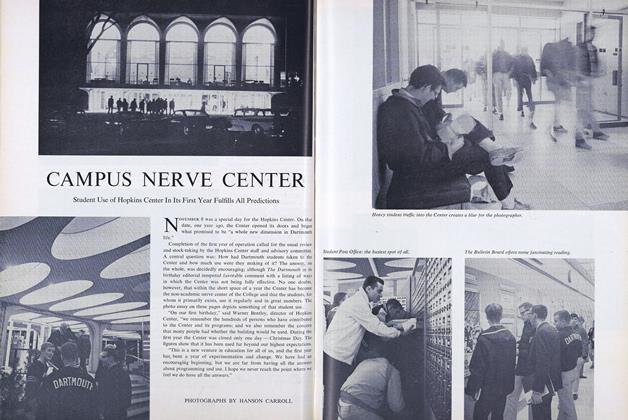

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

DECEMBER 1963 -

Feature

FeatureLife with Uncle

APRIL 1967 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMR. SCHOLASTIC

FEBRUARY 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureMy "Most Unforgettable Character"

February 1954 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Feature

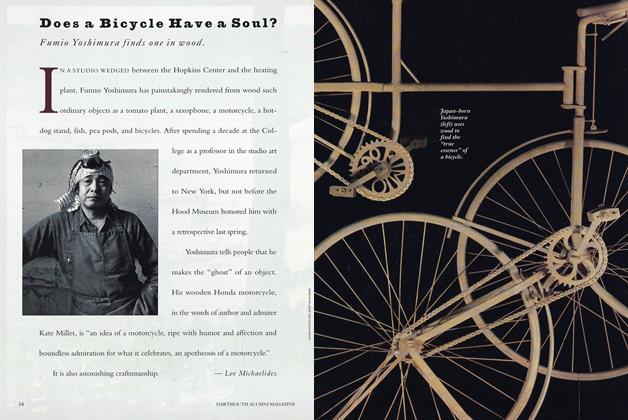

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides