(From conclusions of Education and Military Leadership)

THE ROTC programs must be reshaped to meet the new security requirements of the nation in a nuclear age. They were originally designed to prepare large numbers of reserve officers who would be called to lead a citizen army mobilized in an emergency. But today our security requires forces-in-being at all times, commanded by career-minded professional officers. Finding the full number of these officers is one problem. Finding the right kind is even more difficult. These men must possess more than the traditional military skills; they need wisdom and intellect of high order, and must understand the qualities and complexities of our democratic society.

The Army, Navy, and Air Force are not alone in their search for such talents, however. Other professions have similar requirements, and are willing to meet them with a variety of attractive inducements, placing the services in a tight competitive position. The Air Force, for example, lacks enough trained pilots willing to stay in service to man critical units. The Army, likewise, needs more men than it is now getting for regular commissions in special scientific and technical fields.

The service academies alone cannot meet the demand for career officers. Only our colleges and universities provide an adequate pool of the varied skills and talents that are called for. The services are now attempting to utilize the ROTC programs, once designed for another purpose, for this new objective. Already the Army, for example, is commissioning each year more regular officers from the ROTC than from West Point. Both the Air Force and the Navy have increased the service obligation for most ROTC graduates in order to promote more careermindedness among their cadets and midshipmen.

Nevertheless, the incentives in the present ROTC programs are inadequate to the needs of the services. There remains a wide gap between the kind of talent needed and what the armed forces get. Few young men enter college clearly motivated toward careers in the public service in any capacity. Of these even fewer, and hardly the best, turn to the military profession. The vast majority join the ROTC only as an alternative to being drafted as enlisted men, with little intention of staying in beyond the obligated service.

What this amounts to is that pro-fessional officer requirements cannot be met through the operation of the open market of career opportunities. In this situation the federal government must take positive action to meet a critical manpower shortage. There are precedents in the ROTC programs themselves for increasing the incentives in order to encourage the best college graduates to enter active duty with the thought of making their careers in the military service. Since 1947 the Navy has operated a small, subsidized program under which carefully selected students, so-called "regulars," are educated at government expense, in return for an active duty obligation that is presently four years. The federal government should provide similar arrangements for the Army and Air Force. Unless the services can compete favorably on the campuses of the nation in the annual talent hunt they are not going to get their share of the most competent young men.

Federal support of this nature is not enough, however. The substance of the ROTC programs must be changed in order to provide an appropriate pre-professional experience for a military career. All too frequently ROTC instruction is unimaginative and less than first-rate. Classroom content must be minimized and military training accomplished in extracurricular drill and laboratories and in longer summer camp and cruise periods. The student must devote his on-campus time to a broad educational preparation for later training and specialized technical and professional schooling. After all, even West Point graduates receive the greater portion of their military training after commissioning.

The purposes of the subsidized ROTC programs should be to recruit, motivate, and educate potential career officers. As in other professional programs, they should include no more detailed training than that actually required to enable a rookie officer to get started on his first duty. This, for example, has been the trend for some time in engineering. As these changes are carried forward, it will be possible to lower enrollments in the programs and to reduce the total number of ROTC units, making for a more efficient and less costly effort.

The main thing is to make certain that the services get the talent that they desperately need. Given the security requirements of the nation on one hand, and the ever-increasing career opportunities now available to young men of ability on the other, the federal government should support pre-professional military education in the nation's colleges as well as in the service academies. Indeed, this is the one field in which the purpose and obligation of the federal government are clear, and in which it can properly provide aid without compromising the decentralized, pluralistic character of American higher education. Not to do so would be either to forfeit the strength of the armed forces at a dangerous time in history, or else to build that strength on less than the broad democratic base of our educational system.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

May 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

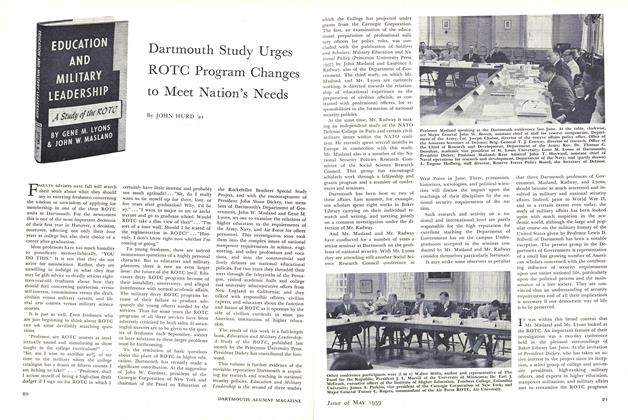

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

May 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

May 1959 -

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

May 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, JAMES LeR. LAFFERTY

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH PLAQUE RECEIVED BY EVANSTON HIGH SCHOOL

July 1918 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

March 1960 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Giving Adds $13 Million in Year

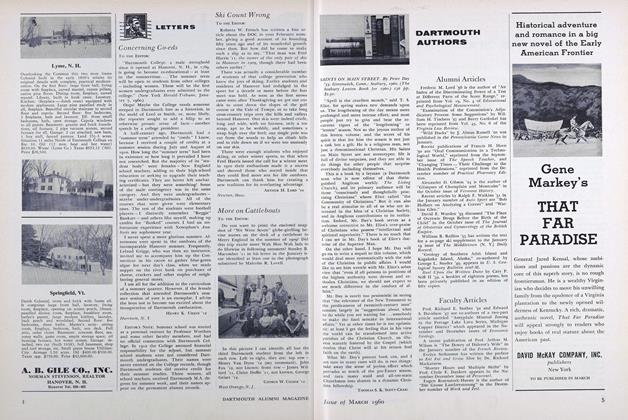

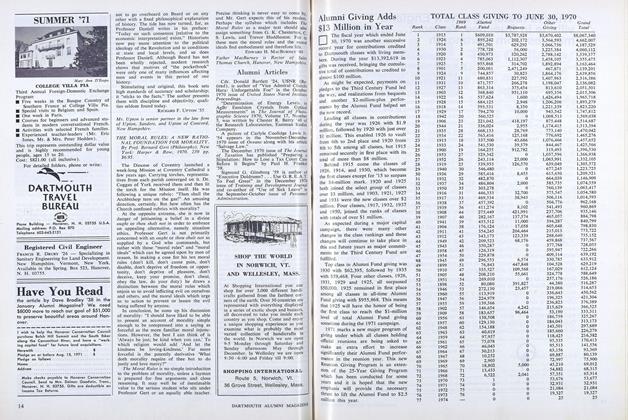

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleA New Librarian

April 1979 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in New York

March 1938 By Milburn McCarty '35 -

Article

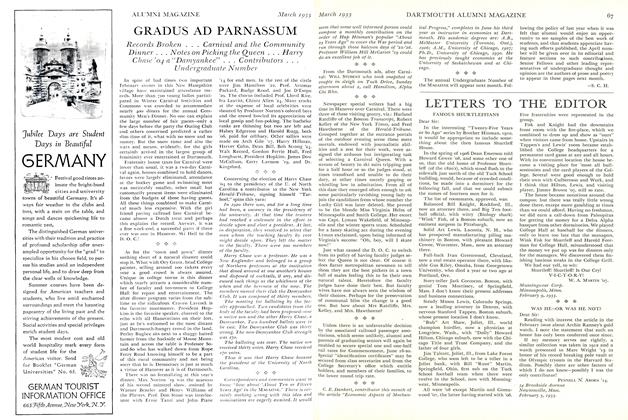

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

March 1933 By S. C. H