PROFESSOR OF AMERICAN HISTORY, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

I'M going to skip nimbly through an untouched topic. I wish to say something this morning about education. I know that has a forbidding sound, but not quite so forbidding as history, perhaps, and I shall try to make it, at least in spots, reasonably attractive. Now every educator knows that group predilections and group antipathies, rising largely from what the English psychologist Trotter called the herd instinct, offer a curious study. But he also noticed that in this field it is important to distinguish between the superficial and the fundamental. Oscar Wilde remarked of the young Bernard Shaw, "He has no enemies, but all his friends dislike him." Shaw would have said, quite correctly, that this did not matter; that it was important not that his friends like him, but that they esteem him. That is the position nations should take. Britain, Canada, the United States find much in each other to dislike, and always will, but the essential desideratum is that underneath their accords and discords should always lie a solid mutual esteem, an unconquerable trust - and that is a responsibility, in a large sense, of education.

Now some speakers were saying yesterday that Stalin had made the Anglo-Canadian-American alliance, which I am positive is a misinterpretation of what Sir Geoffrey Crowther said. Stalin contributed to it; he did not make it. AngloCanadian-American solidarity long antedated the last decade. The three nations fought side by side in the First World War, for aims far transcending national safety - aims stated by Lloyd George, Robert Borden and Woodrow Wilson. Between the wars they coined the phrase "the Atlantic Community." Long before the United States entered the Second World War we reaffirmed the old solidarity in the Atlantic Charter. It is true that when the Second World War ended many Americans hoped that Wendell Willkie s dream of One World could be realized, and in that dream were ready to show special cordiality to a Russia reclaimed from her old hostility. Many Britons shared that dream; to some of us Americans it seemed the British Labour Party was more partial, for a time, to Russia than to America. But the founuations of Anglo-Canadian-American solidarity were not really shaken. Winston Churchill said he could never understand why Russia threw away so tremendous a fund of good will. But even had she not done so, the closer ties, as I am sure Sir Geoffrey agrees, would have remained the Atlantic ties. Why? Because our solidarity is planted on an old, welltested, perdurable mutual trust. . . .

This fact permits me to set forth a syllogism, or at least a series of related theses, which run as follows:

First: The foundations of a good understanding must in the last analysis be intellectual and moral, not materialistic. I quite agree that the foundations must not be sentimental; they must be based on reality. But we are looking at the ultimate realities, when we say that the foundations must be intellectual and moral.

Second: The essence of this moral and ideal foundation is a common devotion to the protection and development of freedom for which we have fought side by side. This devotion emphasizes the fact that modern freedom is increasingly social rather than individual. It also emphasizes the development, the growth, of freedom far more than its mere defense.

Third: Freedom for the English-speaking peoples has a common history running back to Burke, to Locke, to Harrington and Sidney, back to the foundations of the British Constitution - and running forward to those principles which are expounded in the Court of the United States in the State of Arkansas, by a judge reared in the traditions of Anglo-American law - a history that both in its earlier and its latter days cannot be too much studied.

Fourth: Freedom for these peoples also has a manytrumpeted interpretation, an exposition written by a thousand pens; it lies in great literary productions of the Englishspeaking peoples - perhaps the noblest literature of the globe and one incomprehensible except to those who understand freedom.

Fifth: The most vital problem, therefore, in maintaining our solidarity is the problem of the consistent and planned education of the three peoples in the noblest part of their common history and their common literature. This means education in elementary school, high school and college; in newspapers, magazines and the mass media generally; in cheap editions of the best books scattered throughout the three nations; and education through the pulpit, the bar, and the editorial desk. It includes education by the frequent enunciation of basic principles on the part of great public leaders. . . .

How can we grasp the full meaning of freedom? There are but two royal roads. It is only by studying it in our common history and our common literature. Sir Oliver Franks, after his sojourn in Washington, spoke of "the frictions of association," by which he meant the frictions of partnership. Each nation would prefer to go it alone, as in the old days when Palmerston bore sway in London and Lewis Cass was a bumptious American Secretary of State. The British do not like having an American Administration modifying their policies, while the Americans dislike having the British limit their choice of action. How hard it was for the British to find an American made Admiral of the Atlantic! But these frictions of association can be regarded far more sanely and wisely by men steeped in the age-old trend of Anglo-Saxon development, in our secular devotion to freedom, than by the ignorant. Such education in itself chiefly explains the difference in attitude between an Elihu Root and a William Randolph Hearst. To impart it on a massive scale, or at least bring it within the reach of everybody—surely this is the greatest aim we can set ourselves. It is important to rectify bad tariff schedules. It is important to send British lecturers around on what Dylan Thomas called a middle-aged whisk through the middle western universities. It is important to keep American lecturers in England giving such instruction that no visiting Briton will ever commit the fearful blunder that the Prince of Wales made in Philadelphia in 1860, when he asked, "What is a Biddle?" It is important to know the proper pronunciation of "schedule" — something that General Eisenhower told Marshal Montgomery he had learned when he went to "school" [pronounced "shool"]. But how infinitely more important is the shared knowledge of the history out of which has grown the political and social principles we live and die by. How immeasurably more potent is a common saturation in the literary masterpieces which express the thought and emotion of our finest spirits.

It is true that the course of English-speaking history has often been capricious and uneven; that it abounds in discords and even fratricidal quarrels; that the record contains crimes, follies and misfortunes we would gladly blot away. But it is nevertheless on the whole a chronicle of an infinitely brave, toilsome and victorious upward climb. From all the confused effort, strain and turmoil, the shouting of crowds, the clangor of armies, the roar of wheels and whistles, the voices of leaders, emerges one impression given in equal degree by the history of no other people: the impression that in this smoky workshop was being forged the greatest treasure a race can possess, Character. . . .

What practical steps can we take to ensure a better education in our common history and common literature? How, for example, can we make sure the next generation of Americans and Britons will realize what a striking example of the larger freedom Canadian history offers in its record of the successful merger of British and Protestant Canada with French and Catholic Canada; not two separated and embittered peoples, but one well-fused nation, Canadians all? How can we get more Britons and Americans who know what gave Emerson and Carlisle their earnest friendship? For Americans, a minimum program would include at least these steps:

First: A widespread restoration of courses in British history in our high schools. A generation ago when I went to high school in the State of Illinois, a course in British history was required. From no course did I derive more. How sad it is that that course has died out in our American schools.

Second: The strengthening of departments of British and Commonwealth history in our universities and colleges. Nearly all of them offer courses, but in few fields is there now a greater dearth of distinguished teachers.

Third: The restoration of British and American classics in literature, from Chaucer down to Kipling and Howells, to their proper place in our secondary schools. A generation ago these classics were the core of liberal education. Every high school student knew Macbeth, II Penseroso, The Vicar ofWakefield, Silas Marner. Today we cannot be sure a high school graduate will know a single classic. Courses in contemporary reading - newspapers, magazines and current books - have too largely taken their place. A member of the Chicago school board exclaimed several years ago, "Thank God we have gotten rid of those fusty English classics." He little knew what he had gotten rid of.

Fourth: A more abundant offering of courses in Canadian or Imperial history in our colleges.

Fifth: Ever more diligent effort to make the best literature of Britain, Canada and the United States available at low prices throughout the English-speaking world, as in the Everyman Library, the World Classics, and various editions of pocket books.

Sixth: A keener appreciation among those who control the mass media of the importance of enunciating and illustrating the historic Anglo-American principles of freedom and democracy.

We can take encouragement from tokens of recent progress. The very wide American circulation of Penguin books, especially in colleges and universities; the fact that Sir William Haley's London Times Literary Supplement, so much the best organ of its type in the world, gives almost as much space to American as to British publications; the way in which the contributions of American scholars to British history and literary criticism are being repaid by British work in American fields - these give us special gratification.

Henry Hallam in his history of the Middle Ages asserts that the famous victories of Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt were not to be credited to superior tactics or greater valor. "These victories," he writes, "and the qualities that secured them must chiefly be ascribed to the freedom of our constitution." That was an irrefutable truth. An emphasis on character, and that character rooted in freedom; a devotion to principles of law and justice - these have won the Englishspeaking world all its past victories, and offer the promise of more to come. We can say with Wordsworth, "In our halls is hung armoury of the invincible knights of old" - and the more we understand that fact, illustrated by so many heroic events, and hallowed by such immortal literary monuments, the more unassailable will be the foundations of our unity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

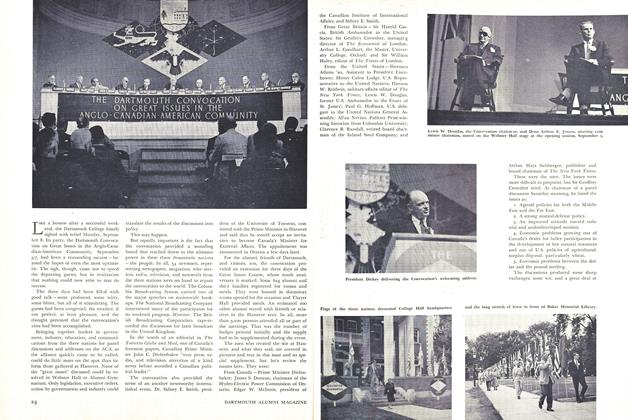

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

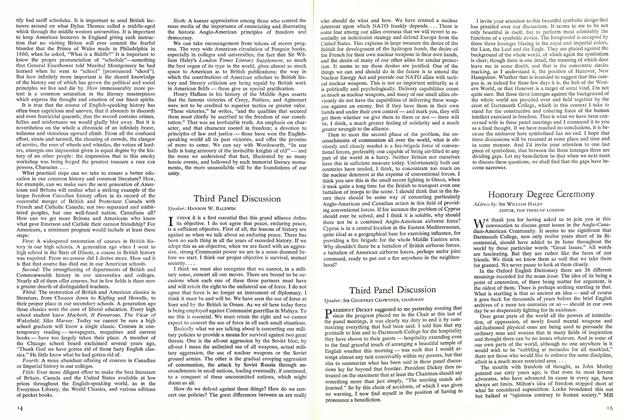

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA CITY VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS

JUNE 1963 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Feature

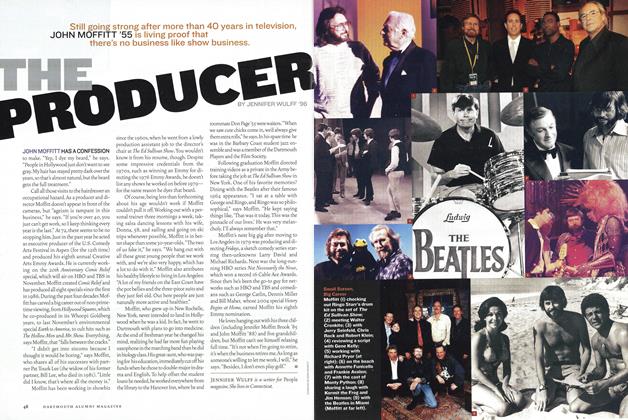

FeatureThe Producer

May/June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureOpening Assembly

October 1951 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

JULY 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65 -

FEATURE

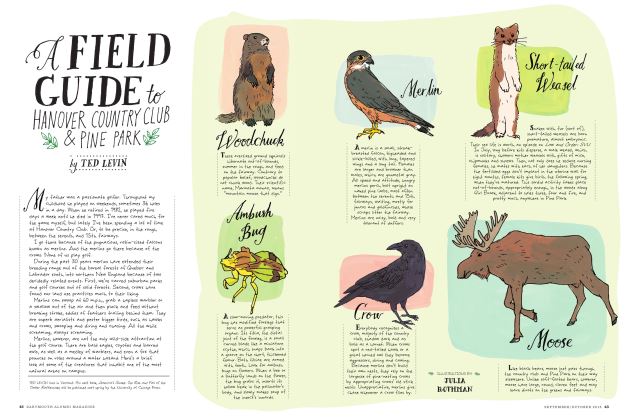

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By TED LEVIN