PROFESSOR OF MUSIC

OUR age is said to be a social and political age and in scanning the horizon of our time, one can doubt very little that the prime phenomenon of socio-political occurrence is rivaled in importance in our ideas only by our concepts of the importance of science. Indeed, it has often been observed that Twentieth Century man treats science virtually as a religion, so that the socio-political make-up of the democratic and authoritarian states of our century is characteristically countered or supported by a kind of scientific mystique.

In this same century there has come to be a concept of art which treats art as a purely socio-political phenomenon and, in essence, reduces the status of art to that of a viable commodity. Webster says that a commodity is "that which affords convenience or advantage, especially in commerce." The size of the record industry, of the business of music entrepreneurs, yes - and the response of the rising generation of college students at Dartmouth and elsewhere seem, superficially at least, to verify such a commodity theory. In the 1930's under the impact of the Depression and the emphasis on mass media engendered by World War II there had grown up the cult of the "common man" and its art was an art of simplification. It was during this period that the "simplified" music of Shostakovitch and other mass-minded, politically-minded musicians had its heyday. All the arts including music were in crisis and it was a matter of survival under the cruel inroads of depression that creative men across the globe turned to writing folk-inspired, propaganda-like music to reach the only patron - the mass public - who could afford the artist's services.

With the return of comparative economic and political stability and the coming of the era of prosperity following World War II, however, a counter-revolution against the art of the common man occurred. Against the documentary and sociological specifications which had been drawn up for the arts by the precepts of so-called "socialist realism" and social action art, there came after 1945 to be a sense of the pure and abstract in art which dwelt on the highly speculative. The school of "abstract expressionism" in visual art of the last fifteen years has been matched by a speculative and abstract approach to the organization of sounds in music.

The division into camps of musical opinion of chief creative figures regarding problems of musical organization since World War II has brought into play diametrically opposed ideas of the nature of "order" to which a composer should subscribe. Thus, Igor Stravinsky, a composer whom one naturally tends to believe through the sheer fame of his achievement, takes a very opposing point of view on problems of order in music from the points of view adopted by many of the most impressive young creative men of music. Certainly, Stravinsky has said in many places that we must "bring order out of chaos . . . order and discipline" and he points out in his Poetics of Music, "to proceed by elimination — to know how to discard . . . that is a great technique of selection." But to allow Stravinsky, master though he be, to settle for us the problem is to neglect many impressive younger men who are leaders of the avant-garde whose opinions will most certainly affect the attitude of the general public toward music in due time and have already affected profoundly the whole creative climate of the last half of our century. To these avant-gardistes "order" can be a prejudicial and "loaded" word when taken too literally. To more conservative listeners it is unthinkable that any kind of "disorder" could be the root of a style in the arts and yet - choice of tone combinations and successions decided at times by some random, "irrational" method, as is sometimes the practice of young composers of the last decade, may be only a means of achieving a more subtle order than that used in more classic musical styles. Were it not for the large number of impressive talents who have subscribed to "irrational" concepts, we might dismiss the whole movement as a fad. Suffice to say that the existence of such an international gathering place of avant-gardistes as the Kranichsteiner Musikinstitut in Darmstadt in West Germany is in itself an astonishing proof of the widespread nature of this movement.

Of course, many listeners do in part subscribe to some kind of a utilitarian test of art which Robert Frost once aptly dubbed "trial by market." There is no doubt, for example, that musical expression like jazz and folk music addressed to a large public will continue to exist. However, the thoughtful connoisseur of even that "public" music also is not devoid of real suspicion of what is calculatedly "commercial."

With the elements of chance or calculated "disorder" such as is possible in music produced by a large mechanical synthesizer of sounds a real paradox results. We behold the production of music by automation methods but in such a way as to resist the standardization which is usually thought to be an unavoidable concomitant of automation.

The mention of automation brings up the question of how one applies such techniques to the field of music. The most convenient means of defining the process is to refer to a recent authoritative book, Experimental Music, written by Hiller and Isaacson, in which the following prolegomenal statements are made: "We shall limit our discussion arbitrarily to novel means of composition and sound production, and, moreover, we will stress the difference between attempts at rationalization of the laws of musical composition and attempts to substitute and make use of modern means of sound production to produce an aural effect. Thus, we will immediately exclude from consideration forms of composition involving either a composer writing music on paper in the traditional sense or experimentation with novel sound effects and timbres utilizing conventional musical instruments. In so doing, we are, of course, not at all implying that significant new music is not being written by these more traditional procedures; we are simply restricting our discussion to the most directly related material. Secondly, given this restriction of subject matter, it seems convenient to classify current research in experimental music into two basic categories: (1) We can group together experimental studies of the logic of musical composition. In terms of most recent work, this would refer most specifically to the use of automatic highspeed digital computers to produce musical output. For convenience, we may term such music computational music, in general, and the specific type produced with computers, computer music. (2) We can consider experiments involving primarily the production of musical sounds by means other than the use of conventional instruments played by performers. In this category, we refer to the production of musical sounds by electronic means and by the manipulation of magnetic recording tape in tape recorders and related devices. For our purposes, it is convenient to group all these experiments under the name of electronic, or synthetic, music. In this second group of experiments, principles have had to be formulated for 'composing' as well as for the actual technical production of sound, but the choice process for selecting materials to go into a 'composition' is still carried out entirely by the 'composer'."*

Later in the same chapter the authors identify two principal types of music in part or in whole synthetic: namely, musique concrete and electronische musik. The former type, developed by a group using facilities of the Radiodiffusion Francaise, utilizes "only sounds which originate in nature." The "natural sounds," however, are subjected to considerable alteration during the course of "composition" by means of several pieces of equipment. The latter type, that of electronische musik, is the sort prepared at the Nordwest Deutsche Rundfunk studios in Cologne and utilizes sources of synthetic rather than "natural" sound. It is further pointed out that, "In contrast to musique concrete, much of electronische musik sounds simple and almost primitive. Simple sine-wave tones [a type of fundamental tone constituting the large proportion of total sound of electronische musik], relative to which the most familiar instrumental equivalent is the recorder, lack harmonics and are, of course, neutral and unexciting in effect."

To return to our interrogation, "How Public Is Music?" - one can readily see that such serious developments in the art of music gravely modify the composer-audience relationship. The mere fact that the performer is eliminated in much experimental music relieves such music of the character of an "athletic event" which in part endears the renditions of virtuoso performers to the hearts of their listeners. Yet, as noted, the practitioners of experimental music do not contemplate the elimination of more established methods of creating or performing music. Indeed, one cannot easily foresee any cessation in production of such widely public music as that produced for the Broadway show by a Richard Rodgers or for a folkmusic ballet by an Aaron Copland.

Trying to dismiss the new experimentalists as "headline seekers" or merely bizarre "beatniks" is not apt to prove successful, however. Already in the past year the Rockefeller Foundation has granted $175,000 for the equipment and operation in New York of a studio for experimental music to be run by a commission of four composers: Otto Luening and Vladimir Ussachevsky of the Columbia University department of music and Milton Babbitt and Roger Sessions of the Princeton University department.

It was one of these composers, Milton Babbitt, in an article published in High Fidelity magazine in February 1958, who pointed out that much of the expert writing in music of our time, despite its great competence, has little or no appeal for the general public. It has become therefore in economic terms what might be termed a "negative commodity" or "negative utility," having no "practical" value. Babbitt calls on educational institutions to regard such music as a subject for research, with the same virtues as research in any science where some but by no means all that is produced will prove of value.

It would appear therefore that we live in not one world of music but in many worlds of music, in which one just now developing is the world of "research composition." To be sine the old musical values are not destroyed but a new dimension is added to them. There appears no indication that ultimately music will cease to be a matter of communication, but we must not use demagogic means for making it so. Even so accepted a composer as Beethoven wrote in his final years of life the so-called "last string quartets," often considered by critics as the epitome of his genius. The fact that these quartets appeal to only a very small fraction of the musical public is no discredit to the quartets or to their composer.

Or let us consider the case of the most potent influence on post-World War II composers - Anton Webern, born in 1883, famous as a Schoenberg pupil whose work was nothing more than a legend to contemporary music lovers outside of his native Austria and who was killed, according to report, accidentally by a bullet fired by an American soldier in 1945 near Salzburg. It was not until 1947 that the present writer heard important examples of Webern work and yet by 1957, no less a person than Igor Stravinsky, formerly regarded as an unmitigated opponent of the Schoenberg theories, declared Webern to be " 'just before music' (as man can be 'just before God')." Such eloquent testimony is hard to rebut.

But even more important than such testimony to Webern's greatness is the influence of his assumption with regard to sound. For example, in traditional theory of music we assume that a given tone like middle c on the piano can be made interchangeable with certain c's of other registers. Webern denied this interchangeability and in effect said that every tone and every tone quality has an individual life of its own and helps by token of that individuality to define the scope and limitations of the sound complex of which it is an element. Thus Webern's music, although produced on conventional instruments, causes to emanate from those instruments many unique sounds, terse and microcosmic. The transfer of such a concept of the self-sufficiency of each musical sound to the concept found behind experimental music using electronic methods apparently was achieved without delay in the minds of many creative musicians following the commercial issuance of tape recording equipment around 1945. Almost as if to enhance the affinity which has been established in latter-day creative musical thinking between the composer Webern and the experimentalist composers, Columbia Records about three years ago issued the complete works of the Austrian composer in an album which has had little prospect of "selling" in large quantities.

Some years ago Life held a symposium on uses of leisure time entitled "The Pursuit of Happiness." In this the philosopher, Theodore Meyer Greene, pointed out the strong evidence that truth in our time is complex and difficult of attainment and that this characteristic imbues even the art of this period. He then proceeded to show that the layman of the Twentieth Century is loath to accept this artistic complexity even though that same layman would never have presumed to say to Einstein regarding that scientist's writings, "Don't be so difficult." Undoubtedly some remonstrance will be forthcoming to prove that the artist-musician must communicate" and implying that there is an aesthetic obligation for the artist thus to communicate. Suffice to say it would be historically a Herculean task to prove that Bach was concerned primarily with lay audience reception when writing The Art of Fugue or that Beethoven had any such prime objective when writing his String Quartet, c sharp minor, Opus 131, masterpieces of musical writing though these two compositions be.

What then for the colleges and universities of our time are the inferences of the foregoing data? They reveal themselves as follows:

1. Music is not always to be conceived of as a commodity or as a "social document" although it at times partakes of the nature of these.

2. The study of music in a great many of its latter-day creative manifestations appears destined, in part at least, to become a new subject of subsidized research much as physics and chemistry found their way as new vigorous and valid subjects into such research status in educational institutions in the Nineteenth Century. Thus to the company of musicologists, music theorists and music historians who have been granted a "research status" among the company of scholars must be added since World War II the creative music experimentalist.

3. The public response to music is but a fraction of the means by which we test the truth of music and it appears that some placement of music with sciences like arithmetic, geometry and astronomy, as was the case when these four sciences constituted the Quadrivium of the medieval seven liberal arts, is before our very eyes again in "the process of becoming."

A Suggested, Discography

1. Examples of "conventionally performed" pre-electronic music. A. Webern: The Complete Works, Columbia Records, K4L-232 (4 records).

2. Example of "conventionally performed" work strongly influenced by electronic music. K. Stockhausen: Nr. 5Zeitmasse, Columbia Records, ML 5275.

3. Examples of music produced in part or entirely by electronic means. O. Luening and V. Ussachevsky, Rhapsodic Variations for Tape Recorder and Orchestra, Columbia Records, Louisville Series. O. Luening and V. Ussachevsky, A Poem of Cycles and Bells; Suite fromKing Lear, Composers Recordings, Inc., CRI-112. John Cage, Retrospective Concert, address George Avakian, Box 374, Radio City Station, New York 19, N. Y. $25.00.

4. Examples of Musique Concrete. P. Schaeffer, P. Henry, P. Arthuys, and M. Phillipot, Panorama of MusiqueConcrete, Vol. I, London DTL 93090; Vol. II, London DTL 93121.

* From Chapter 3, passim, of Experimental Music by Lejaren A. Hiller Jr., Asst. Prof, of Music, Univ. of Illinois, and Leonard M. Isaacson, Mathematician of Standard Oil Co. of California and formerly Research Associate, Univ. of Illinois. McGraw-Hill Book Co., N. Y., 1959.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFIFTY YEARS OF THE DOC

February 1960 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Feature

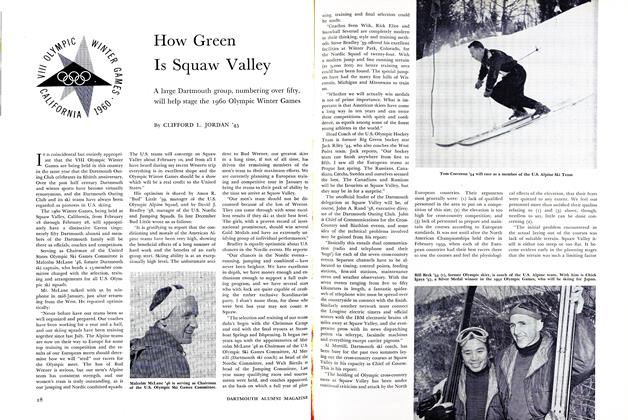

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Broadcasters and the Government

February 1960 By ELMER E. SMEAD -

Feature

FeatureIndividuality in Forest Trees

February 1960 By F. HERBERT BORMANN -

Feature

FeatureA Pioneer in Electronics

February 1960 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleOur Mark Twain

February 1960 By STEARNS MORSE,

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

MARCH 1964 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Makes Four Awards

JULY 1966 -

Feature

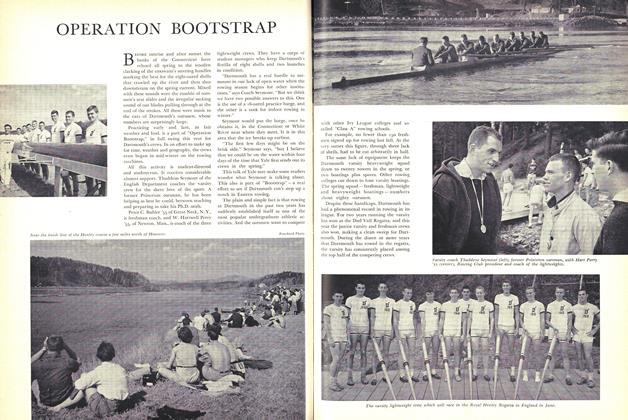

FeatureOPERATION BOOTSTRAP

June 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

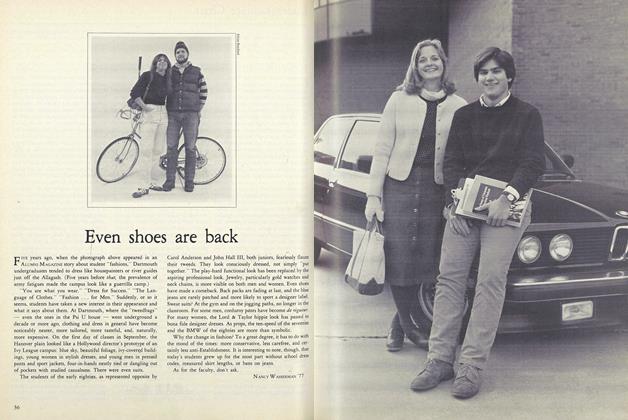

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

DECEMBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

JULY 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65