"...the echoing horn no more shallrouse them from their lowly bed."

THOMAS GRAY

TRADITIONS, like habits, are varied in character. Some are worthy of continuance, gaining strength with age. Others develop slowly from innocent foibles to become glaring eccentricities which show up as chinks in the moral armor. In the case of the latter, appeals to reason are of no avail. Their strength has to be thinned by the tides of time until they wane with the passing of adolescence and finally disappear with maturity.

Thus it was with the habit, or tradition, of "horning" at Dartmouth. It remains as an old wives' tale in the minds of a hand- ful of octogenarians - and it remains re- corded in the histories of Chase, Lord, and Richardson. It will be set forth here as a chronicle of times that are gone.

Apparently it all started with President Wheelock, who used a conch shell to announce the call to chapel, an exercise which preceded the day's classroom activity. It was a raucous, indelicate noise eliciting the same irritated response that might be evoked by the hum of a mosquito or the scratchy sound of a hard piece of chalk on a math professor's blackboard.

Fortunately, one of Dartmouth's earliest benefactors, George Whitefield of England, presented to Moor's Charity School a bell which had a more dulcet sound than the conch. However, for some years a horn of unknown timbre, tone, pitch, and quality was also kept on hand to supplement the bell which would fail on occasion, particularly when the bellrope was severed.

The horn still persisted, for the student body, as the phonic call to assembly - like the beating of drums, the firing of cannon, or the sounding of sirens. It was a most impersonal means of expression, and at Dartmouth the ownership of a horn became a necessity, quite as desirable as an alarm clock, a college banner, or a Livy trot. A local merchant of great enterprise maintained a stock of tin horns, probably produced by James Roby who operated a tin shop close to where Putnam's drugstore now stands.

Horns were safety valves, to be popped when tensions had risen either within the individual, the dormitory family, or the complete college congregation. Waves of horn blowing would seize the campus with a din that would become almost unendurable. In 1835 the faculty attempted to bring about quiet by regulation, and President Asa Smith decreed that "students refrain and abstain from loud noise." As well try to suggest that the Connecticut cease to flow under Ledyard Bridge.

According to Josiah W. Barstow, 1846, tooting was still in full vogue during his entire undergraduate years, even when expulsion was threatened to any student caught with a horn in his hand, or even found in his room.

In July 1851 there was a tremendous celebration at St. Johnsbury to mark the opening of the Passumpsic Railroad. Several hundred students went north on the excursion train, and according to unexpurgated reports raised such "hell" with their horns that the faculty took up the matter for disciplinary action. This brought forth an outburst on the Plain on July 12 which lasted for several hours. The net result was the separation of eleven students, probably based on the formula of V X D (volume times duration) . From then on trumpeting was limited to times when the students wished to express dissatisfaction with the actions of their instructors.

It was a simple matter to interrupt recitations by tooting outside a classroom, and then scuttling to shelter. At night there might be a concerted action, often by men in disguise. A member of the faculty who had aroused undergraduate antagonism was likely to find his home surrounded in the dead of night by a horde of "masked barbarians" who would awaken the neighborhood with all the eerie noises which human ingenuity could produce, tearing down fences and carrying off gates, throwing snowballs in winter and less attractive missiles at other times. Investigations always followed, with severe penalties. But, somehow, permanent improvement could not be brought about.

Probably the most notorious horning episode occurred in February 1883. A popular member of the Class of 1885 announced that he was leaving Hanover because of alleged ill treatment at the hands of Professor John K. Lord. It was thereupon decreed that Johnny Lord should be "horned." The sophomore class made its way stealthily to the Greek Room in South Dartmouth Hall, and forty of them awaited the witching hour of 11 p.m. All wore disguises. Although the class's departing member said that Lord really had nothing to do with his leaving, the group decided to proceed with the program, and set out for the professor's residence. Horns blared, snowballs beat against the house, the doors were pounded, and fences broken. Professor Lord appeared scantily clad, causing a precipitous withdrawal. The pedagogue gave chase, fell into a snow-bank, and lost his shoe. But he had identified a few of the participants and reported them to President Bartlett.

Every member of the class was subsequently interviewed by the President, but he found none who would admit his involvement. He called upon the godly ones, and worked on their religious scruples by "appeals to reason, manhood and piety." Finally, after announcing that there wasn't a Christian in the class, he ordered it suspended in toto. He did this "for the present and future order of the College, for the peace and safety of the village, for the good of society and even the welfare and destiny of the young men themselves."

A class meeting followed and a few of the less determined began to falter. Twenty stalwarts voted to resign from college rather than submit. One went to Harvard to arrange for entrance and rooms, but was back in ten days crying, "I squeal. Rah for Dartmouth. Old Dartmouth is good enough for me."

Although Richard Hovey had been in his off-campus room on South Main Street through the whole ruckus, he was one of the first to be interviewed by the President, and of course was suspended with the rest. He wrote to his father that he would leave town forever, and would not complete his course under any conditions. He asked for a transfer to Johns Hopkins, but President Bartlett refused to grant the request until three months from the date of suspension. That would make it too late for entrance into any other institution that year. Hovey stated that if he had been financially independent he would have left anyway. But he stayed on, even though the affair, he says, "nearly broke my love for the college, left me tired, nervous and unhappy."

There are no published accounts of further horning episodes until we read comments about the aboriginal custom in President William Jewett Tucker's autobiography, My Generation. He stated that upon his arrival in Hanover in 1893 he found the need for reform in the matter of the continuance of "certain college customs which had become demoralizing and obstructive." He found that horning was the accredited method of disciplining the faculty, but realized that it could not be treated by punitive action. He believed it to be a fit subject for the exercise of college "sentiment." It was clearly inconsistent with the social progress of the College. He set before the students the innate cowardice of such demonstrations. He made it understood that the habit was out of place and that any who participated thus indicating that they had no conception of the real nature and purpose of the College - would be permanently separated.

Nonetheless, in February 1896 the curtain rose on the final act of our melodrama. An unpopular instructor was assailed by a mob in his office, and a two-hour riot ensued, complete with snowballs and the contents of a coal pile which was found nearby.

Horns appeared mysteriously from nowhere and the party got under way, gathering momentum as it progressed. Word was telegraphed to President Tucker, who was on a mid-west jaunt around the alumni circuit, and caught up with him midway between Washington and Chicago. He immediately cancelled all further engagements, returned to Hanover unexpectedly, and began a quiet and thorough investigation. It had been a class affair and every member was interrogated and asked about his participation. Seven self-convicted leaders were separated, with four more put "under severe censure."

Reports of the episode soon spread, and an unidentified alumni group wrote in protest: "We blew horns in college — look at us now — it's always been the custom since horns were blown at the Battle of Jericho, and always will be. The prestige of the college in the prep schools will be impaired. One of the victims is the grandson of a former trustee. Why don't they discipline the professor who started it all. He should have run away instead of standing his ground."

Despite such alumni dissatisfaction, the student body as a whole did not consider the action of the President unjust or uncalled-for. It was felt, however, that the penalties were unequal in their application, based on the public knowledge of the relative parts taken by different actors in the plot. The faculty was asked to reopen the investigation, to which it agreed. Class and mass meetings were held over a period of a week, with resolutions passed committing the student body to a formal abandonment of the custom.

Thereupon, each involved student was permitted to resume his place in the class. To the deep satisfaction of President

Tucker "college sentiment had finally taken the place of college authority." As an outcome of the largest meeting held by the students, a statement was issued which read in part: "Horning is a clumsy, ungentlemanly and unbecoming method of expressing grievance. It aggravates into violence and personal assault. It is a custom not in accord with student body sentiment - not in harmony with relations which should exist between the administration and the undergraduate group. Therefore, we discountenance and deprecate such disturbances, and will seek to establish other methods of communicating and redressing grievances."

With this the curtain fell slowly, with a happy ending, on a tragic plot that had seemed insoluble. A secret group of seniors was formed with the express purpose of "bringing into close touch and harmony the various branches of college activities, to preserve the customs and traditions of Dartmouth, to promote her welfare and to protect her name."

At the outset this "society" was secret and self-perpetuating, but later the mantle of mystery was thrown off, and it was granted to the upper classes to determine its membership. It represented "the conscience of the College at work." Its name was Palaeopitus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Disappearing Ivory Tower

December 1963 By SAMUEL B. GOULD -

Feature

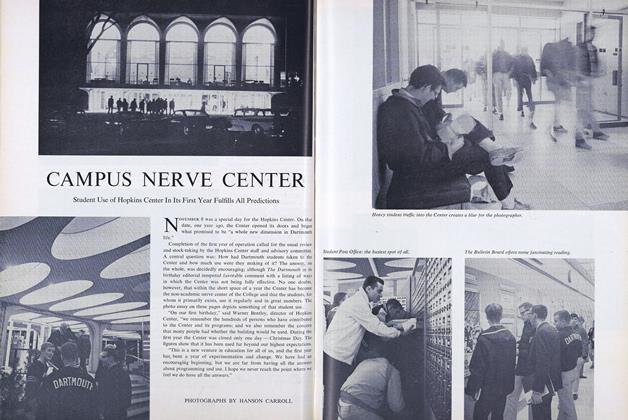

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

December 1963 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1963 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

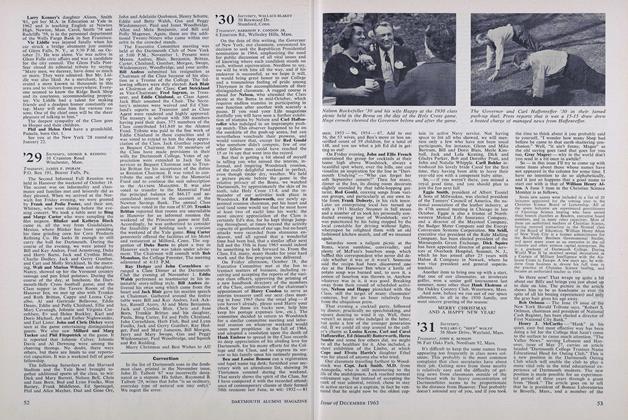

Class Notes1930

December 1963 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

December 1963 By JUDSON T. PIERSON, GEORGE N. FARRAND

HAROLD BRAMAN '21

-

Article

ArticleFor Whom the Bell Tolled

February 1962 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleAle Man

JANUARY 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleLens Artist

FEBRUARY 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleDeep Sea Explorer

JUNE 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleNephrologist

NOVEMBER 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureMovie Producer

DECEMBER 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21

Features

-

Feature

FeatureJOHN PFISTER

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

Featureclassnotes

JULY | AUGUST 2015 -

Cover Story

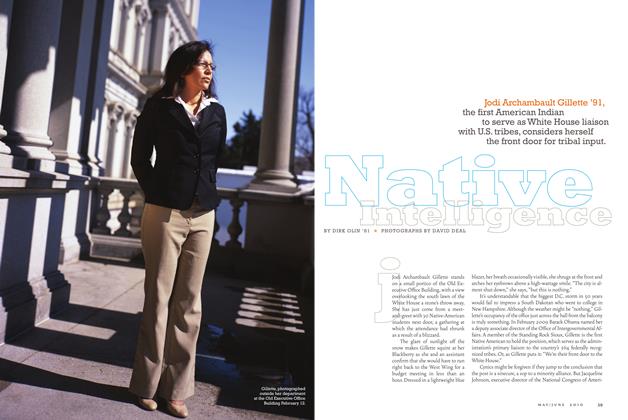

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

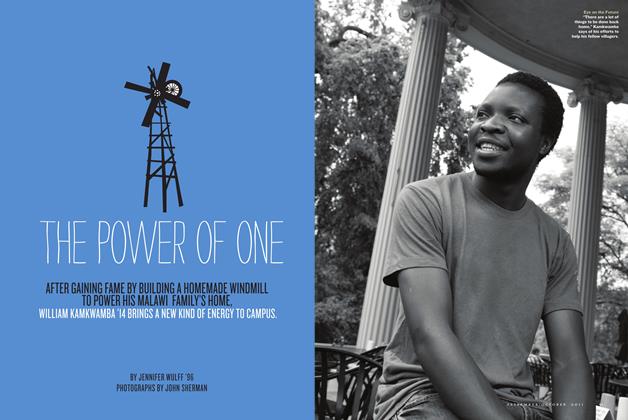

Cover StoryThe Power of One

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

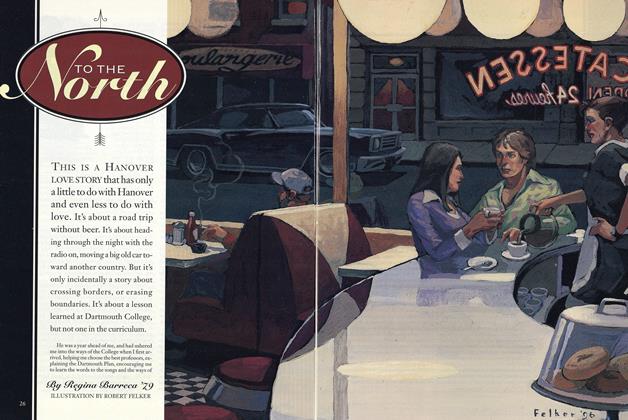

FeatureTo the North

JANUARY 1997 By Regina Barreca ’79 -

Feature

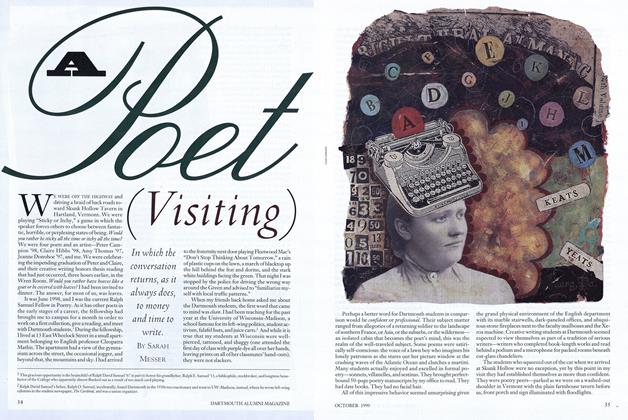

FeatureA Poet (Visiting)

OCTOBER 1999 By Sarah Messer