A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

A BRIEF patch of dialogue in Absalom, Absalom! summarizes the problem of understanding the stories of William Faulkner and, by valid extension, the problem of understanding the South itself. Absalom, Absalom! consists of a long and terrible tale of brutal slavery, miscegenation, adultery, incest and murder told in a Harvard dormitory by Quentin Compson, a Southerner, to Shreve McCannon, his Canadian roommate. The date is 1910. After repeated expressions of horror and sarcastic disbelief Shreve finally cries out:

'Wait. Listen. I'm not trying to be funny, smart. I just want to understand it if I can and I dont know how to say it better. Be- cause it's something my people haven't got. Or if we have got it, it all happened long ago across the water and so now there aint anything to look at every day to remind us of it. We dont live among defeated grandfathers and freed slaves (or have I got it backward and was it your folks that are free and the niggers that lost?) and bullets in the dining room table and such, to be always reminding us to never forget. What is it? something you live and breathe in like air? a kind of vacuum filled with wraithlike and indomitable anger and pride and glory at and in happenings that occurred and ceased fifty years ago? a kind of entailed birthright father and son and father and son of never forgiving General Sherman, so that forevermore as long as your children's children produce children you wont be anything but a descendant of a long line of colonels killed in Pickett's charge at Manassas?

'Gettysburg,' Quentin said. 'You cant understand it. You would have to be born there.'

There are countless studies of the South by sociologists and historians and journalists—and these surely have some value. But just as surely their value is limited because they have only facts to offer us; and facts, while they are comfortable and solid, do not always produce the deepest kind of truth. For the profound revelation which will help us, and Shreve McCannon, to see with Quentin Compson's eyes we must turn to the poet, the creative imagination which can communicate directly the quality of experience, which can make us feel as well as think. And the poet of the South is William Faulkner: his books can give us the knowledge which, according to Quentin, comes only from southern birth.

For over thirty years now Faulkner has been writing a still unfinished series of criss-crossing, interrelated novels and stories about an imaginary part of Mississippi which he calls Yoknapatawpha County (from an old Indian name for an actual river near his home). In the back of Absalom, Absalom! he published a map of the region labeled as follows:

"JEFFERSON, YOKNAPATAWPHA CO., Mississippi.Area, 2400 Square Miles—Population, Whites, 6298; Negroes, 9313. WILLIAM FAULKNER, Sole Owner & Proprietor." This imaginary county and its capital, Jefferson, bear a rough resemblance to Lafayette County, Mississippi, and its county seat, Oxford, where Faulkner lives. But as the mythical world has grown in Faulkner's mind, it has come to represent for him the whole South, and its history the history of the South (remembering always that his ultimate subject is the more universal one of "the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself"). The present essay attempts to describe, with some inevitable distortions, the wonderfully vivid and complex life of Yoknapatawpha County.

The key to this world is its past. Of course every region has some sense of the past: New England, for example, remembers its Puritan heritage. With the passage of time, however, the urgent pressure, the immediacy of the New England past has tended to grow less. The past is still there, it still matters in the bones of the people; but there has been no shattering event to create an enduring sense of regional unity. The Civil War was such an event for the South. Since that catastrophe, as Faulkner tells us in Intruder in the Dust, there has been no passage of time: "For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it's still not yet two oclock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it's all in the balance, it hasn't happened yet. . . Thus the legend of a way of life in the South has been perpetuated by the losing of a war. On that July afternoon time stopped.

Time in Faulkner's novels is not a river but a lake—a stagnant lake with an inlet but no outlet. Events may be added but not subtracted, and all the life of the past is held in solution in that great lake, a fact which may help to explain the apparent chronological disorder of many of Faulkner's narratives. Nevertheless, although Faulkner has moved freely back and forth in the chronology of his stories, we can for present clarity reorder events to trace a continuous history.

As he tells it, this land, while it was still held by the Indians, was rich and beautiful and offered an abundant life to the man who would use it right. It was in fact almost another other Eden, in which man might have a second chance to live in harmony with his Creator. But when the White Man came to settle there, he repeated the ancient sin and put a curse on the land, a curse which is still operative. The sin contained three elements.

First, private ownership of the land. Ike McCaslin puts this case in "The Bear": "On the instant when Ikkemotubbe discovered, realised, that he could sell it for money, on that instant it ceased ever to have been his forever . . . and the man who bought it bought nothing. . . . [God] created man to be His overseer on the earth and to hold suzerainty over the earth and the animals on it in His name, not to hold for himself and His descendants inviolable title forever, generation after generation . . . but to hold the earth mutual and intact in the communal anonymity of brotherhood, and all the fee He asked was pity and humility and sufferance and endurance and the sweat of his face for bread."

Second, physical abuse of the land. After the Indian and the Frenchman and the Spaniard came the Anglo-Saxon pioneer, "the tall man, roaring with Protestant scripture and boiled whisky, Bible and jug in one hand and (like as not) a native tomahawk in the other, brawling, turbulent not through viciousness but simply because of his over-revved glands . . . innocent and gullible, without bowels for avarice or compassion or forethought either, changing the face of the earth: felling a tree which took two hundred years to grow, in order to extract from it a bear or a capful of wild honey . . . turning the earth into a howling waste. . . This pioneer was followed by the planter, who consolidated private ownership and grew cotton on the bare land despoiled of its forests and its game.

But these men did something worse—and this is the third part of the sin—they cursed the land with slavery. In the minds of some, even today, the black man's servitude may be traced to that passage in Genesis where God curses Ham for disrespect to Noah, his father: "Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren." And the Canaanites, or the sons of Ham, according to legend, are the black people of the earth. This legend is referred to by implication in Light in August when Joanna Burden's father exlains why her grandfather and her brother have been murdered in a Reconstruction quarrel over Negro voting rights: "Your grandfather and brother are lying there, murdered not by one white man but by the curse which God put on a whole race before your grandfather or your brother or me or you were even thought of. A race doomed and cursed to be forever and ever a part of the white race's doom and curse for its sins." And then the little girl has a vision in which we may observe that Calvinistic mixture of predestination and human responsibility so characteristic of Faulkner:

'I had seen and known Negroes since I could remember. I just looked at them as I did at rain, or furniture, or food or sleep. But after that I seemed to see them for the first time not as people, but as a thing, a shadow in which I lived, we lived, all white people, all other people. I thought of all the children coming forever and ever into the world, white, with the black shadow already falling upon them before they drew breath. And I seemed to see the black shadow in the shape of a cross. And it seemed like the white babies were struggling, even before they drew breath, to escape from the shadow that was not only upon them but beneath them too, flung out like their arms were flung out, as if they were nailed to the cross.

As a partial judgment for this enormous, compounded sin the Civil War destroyed the wealth and power of the planters and left them to feed on the persistent myth of a bygone Golden Age when Southern Chivalry was in its finest flower. It makes no difference whether there ever was such a Golden Age; the important thing is that the southern aristocrats believe it and that their actions and attitudes are conditioned by this belief. They live in a world of dreams.

There is, for instance, young Bayard Sartoris, who, returning from the war in 1918 and haunted by his brother's death in battle, can find no peace with himself. He drives his car like a maniac, seeking death; and when he succeeds only in killing instead his grandfather, he takes a suicidal job as a test pilot and kills himself that way. His widow tries to lift the Sartoris curse of violent and futile death from her son's head by changing the boy's name. Miss Jenny, also widowed by a Sartoris, asks her bitterly, "And do you think that'll do any good? Do you think you can change one of 'em with a name?" As the two women sit in a darkening room, "the dusk was peopled with ghosts of glamorous and old disastrous things. And if they were just glamorous enough, there was sure to be a Sartoris in them, and then they were sure to be disastrous. . ."

Or, to illustrate once more the presentness of the past, there is the Reverend Gail Hightower, an ineffectual, halfmad minister whose only reality is the death of his grandfather in the Civil War thirty years before he was born; who when he preached "couldn't get religion and that galloping cavalry and his dead grandfather shot from the galloping horse untangled from each other, even in the pulpit." It was "as though the seed which his grandfather had transmitted to him had been on the horse too that night and had been killed too and time had stopped there and then for the seed and nothing had happened in time since, not even him." He was "born about thirty years after the only day he seemed to have ever lived in—that day when his grandfather was shot from the galloping horse. . . ."

The old order, then, is collapsing, sometimes by violence, sometimes by mere paralysis. It goes on vainly living by a glorious and outdated code, full of chivalry and honor and sterile bravery. As one member of the Sartoris family puts it, "There are worse things than being killed. Sometimes I think the finest thing that can happen to a man is to love something, a woman preferably, well, hard hard hard, then to die young because he believed what he could not help but believe, and was what he could not . . . help but be."

And what replaces the old order in power? A new generation of mindless, soulless men full of ambition, with only contempt for the code—or perhaps not even awareness of it. For them there is no past, only present opportunity. This new generation is personified in a back-country family named Snopes. (One critic has perceptively noted the suggestiveness of this name: snoot, snot, snout, snoop, Snopes.) Led by the epitome of pure Snopesism, Flem Snopes, this apparently inexhaustible tribe invades first the village, then the town and finally, entering politics, spreads over the state. As Faulkner presents the Snopeses they are both comic and terrible. They have names like Eck, Mink, Lump, St. Elmo, Admiral Dewey, Bilbo, and Vardaman. There is Montgomery Ward Snopes and Wallstreet Panic Snopes (he is the honest one who spoils the family record). There is even, ironically, Sartoris Snopes. The family activity ranges comprehensively from the idiot Ike Snopes' love affair with a cow through the dirty-picture business of Montgomery Ward to the high financial chicanery of Flem.

Flem Snopes is "a thick squat soft man of no establishable age between twenty and thirty, with a broad still face containing a tight seam of mouth stained slightly at the corners with tobacco, and eyes the color of stagnant water, and projecting from among the other features in startling and sudden paradox, a tiny predatory nose like the beak of a small hawk. It was as though the original nose had been left off by the original designer or craftsman, and the unfinished job taken over by someone of a radically different school or perhaps by some viciously maniacal humorist or perhaps by one who had had only time to clap into the center of the face a frantic and desperate warning." This creature, using such tools as a threat of barn burning, elaborately deceptive trading and his wife's infidelity (Flem is impotent) levers himself into the presidency of the Sartoris bank, a position he regards as an invitation to larceny. Flem's "idea and concept of a bank was that of the Elizabethan tavern or a frontier inn in the time of the opening of the American wilderness: you stopped there before dark for shelter from the wilderness; you were offered food and lodging for yourself and horse, and a bed (of sorts) to sleep in; if you waked the next morning with your purse rifled or your horse stolen or even your throat cut, you had none to blame but yourself since nobody had compelled you to pass that way nor insisted on your stopping."

This fantastic career comes to an end when Flem is shot by his embittered relative Mink Snopes. But Snopesism is not dead. As Gavin Stevens, a remnant of the old order who is an expert in what he calls Snopeslore, says, the coming of the Snopeses is like "an invasion of snakes or wildcats": you may dodge them for a while, but you can't stop them. Faulkner consistently characterizes the low cunning of these creatures by the use of animal imagery. One Snopes, for example, is described as having the "mentality of a child and the moral principles of a wolverine." And we know the Snopes' Progress will go on when Gavin Stevens at Flem's funeral suddenly sees three new but unmistakable Snopesfaces in the crowd: "he thought rapidly, in something like that second of simple panic when you are violently wakened They're like wolves come to look at the trap where anotherbigger wolf . . . died. . ."

Against this background of social and economic upheaval is enacted the tense, explosive drama of black and white relationships. The story of Joe Christmas serves to illustrate this side of Faulkner's single image. An orphan, so named because he was left at the door of an orphanage on Christmas night, Joe is never sure but thinks he has a trace of Negro blood, and he spends his life searching for a racial identity, trying alternately without success to live either white or black. When he is thirty years old, after wandering all over the country, he comes back to Jefferson and moves into a shack behind the old Burden place. There lives alone Joanna Burden, now forty-one, the woman who as a girl had the vision of white babies crucified on a black cross. For three years she and Joe Christmas secretly sleep together. Then when she begins to pray over him for their past sins and tries to reform him, he cuts her throat, sets the house on fire and runs out into the night. Captured, he escapes and in a nightmare chase is run to earth by a dedicated young man named Percy Grimm. Grimm corners Christmas in the kitchen of the Reverend Hightower, empties a .45 into him, and then with a butcher knife emasculates him. Faulkner describes the scene with unmistakable reference to crucifixion and ascension:

When the others reached the kitchen they saw the table flung aside now and Grimm stooping over the body. When they approached to see what he was about, they saw that the man was not dead yet, and when they saw what Grimm was doing one of the men gave a choked cry and stumbled back into the wall and began to vomit. Then Grimm too sprang back, flinging behind him the bloody butcher knife. 'Now you'll let white women alone, even in hell,' he said. But the man on the floor had not moved. He just lay there, with his eyes open and empty of everything save consciousness, and with something, a shadow, about his mouth. For a long moment he looked up at them with peaceful and unfathomable and unbearable eyes. Then his face, body, all, seemed to collapse, to fall in upon itself, and from out the slashed garments about his hips and loins the pent black blood seemed to rush like a released breath. It seemed to rush out of his pale body like the rush of sparks from a rising rocket; upon that black blast the man seemed to rise soaring into their memories forever and ever. They are not to lose it, in whatever peaceful valleys, beside whatever placid and reassuring streams of old age, in the mirroring faces of whatever children they will contemplate old disasters and newer hopes. It will be there, musing, quiet, steadfast, not fading and not particularly threatful, but of itself alone serene, of itself alone triumphant.

For the response of a southern mind to the pressure of such events we may return to the story with which we began. Despite Quentin's assertion that only a Southerner can understand, he has told his story to Shreve McCannon. At the end, the two boys, one from Alberta and one from Mississippi, sit there in the freezing room musing over their subject; finally Shreve says, "Now I want you to tell me just one thing more. Why do you hate the South?"

"'I dont hate it,' Quentin said, quickly, at once, immediately; 'I dont hate it,' he said. I dont hate it he thought, panting in the cold air, the iron New England dark; I dont. Idont! I dont hate it! I dont hate it!" Significantly we learn in another novel, The Sound and the Fury, that a few months later Quentin, tortured by a complex of personal, family and regional hatred and love, commits suicide.

Thus Faulkner's picture of the South is a grim one of a land which, in Irving Howe's phrase, is suspended between "an irretrievable past and an intolerable future." There has been some indication of hope in recent years. In books like Requiem for a Nun and A Fable (not one of the Yoknapatawpha series), though the old images of violence are still there, Faulkner has seemed to be more concerned with salvation than damnation. In no case, however, does he imply that salvation is accessible except through great pain and suffering, and the earlier, darker novels remain his most powerful and convincing works.

It may be argued by some that Faulkner takes as many liberties with history as Shakespeare and is therefore equally unreliable in telling us what has happened, or what is happening. But Faulkner, like Shakespeare, is not a historian; he is a poet who goes beyond history to dramatize for us conditions of mind and soul. Reading Faulkner, one is enabled to live the tragic experience of the South and achieve an intuitive knowledge obtainable in no other way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"What We Are After"

May 1960 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Feature

FeatureNATO in Trouble

May 1960 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31, -

Feature

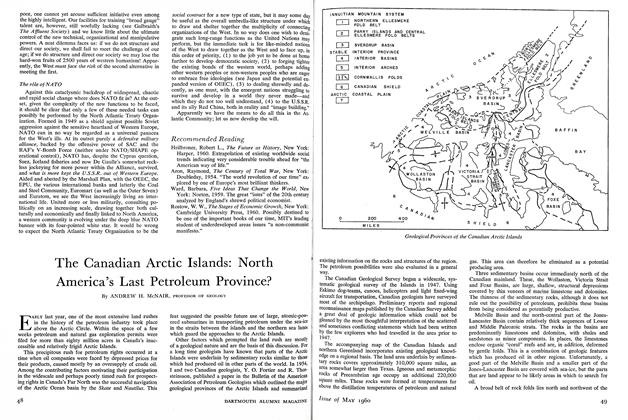

FeatureThe Canadian Arctic Islands: North America's Last Petroleum Province?

May 1960 By ANDREW H. McNAIR, -

Feature

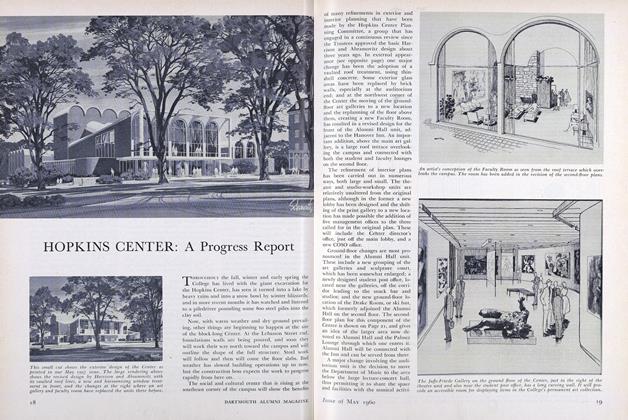

FeatureHOPKINS CENTER: A Progress Report

May 1960 -

Feature

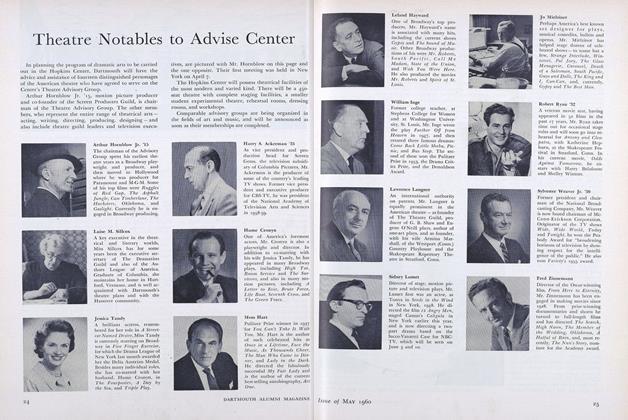

FeatureTheatre Notables to Advise Center

May 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureClassnotes

JAnuAry | FebruAry By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

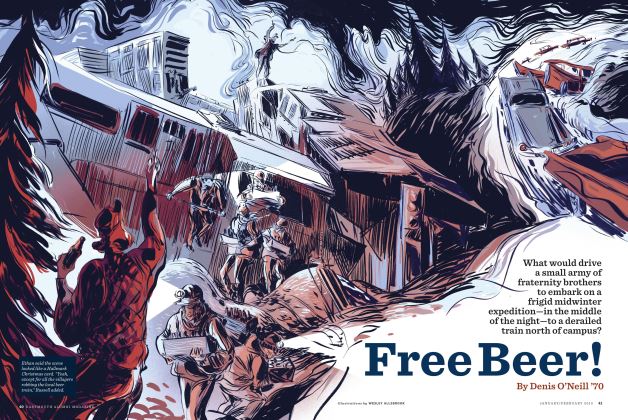

FeatureFree Beer!

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Denis O'Neill ’70 -

Feature

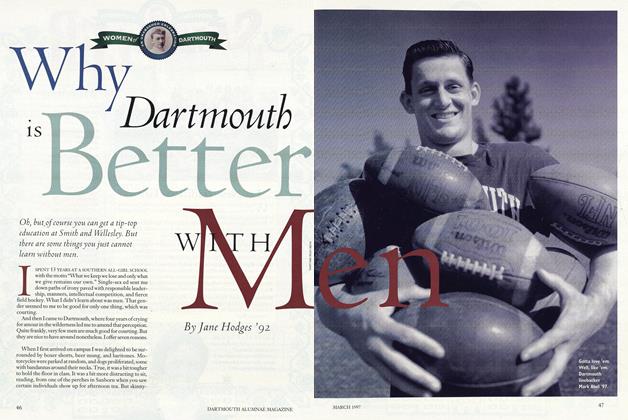

FeatureWhy Dartmouth is Better with Men

MARCH 1997 By Jane Hodges -

Feature

FeatureBeyond the Glory

Jan/Feb 2010 By SARAH TUETING ’98 -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Teri Allbright