SINCE returning to the United States from Russia, I have been asked about the status of the Orthodox Church in the Soviet Union and of religion in general. Although I was only forty days in the Soviet Union as a member of an official delegation of students and teachers, I did manage to obtain a fair impression of contemporary religion in that country.

While we were in Moscow one of our most interesting trips was to the Kremlin where we toured several cathedrals and the state armory. Behind the formidable and centuries-old Kremlin walls are churches, cathedrals and government offices. The religious buildings are no longer open for services but are museums and the resting places of the Russian Tsars up to the time of Peter the Great. We learned that restoration of the Kremlin churches began around 1936 and was continued after the war. Most of the interiors were very ornate with handsomely painted images of saints, apostles and Jesus Christ. The exteriors were in blue and pink adorned with shining gold crosses.

Although the Soviet government insists that religion is for the superstitious and that only old people go to church, we found much evidence to the contrary. One incident in particular showed us that even respect for the long-departed Tsars had not disappeared. A middle-aged woman was seen to genuflect before the tomb of one of the Tsars in Archangelsk Cathedral and to cross her heart.

One day in Moscow a group of us knocked on the door of an Orthodox church near Moscow University and we were admitted. The church was elaborately decorated and on the walls and ceilings were several beautiful paintings of Biblical persons. Back of the altar on the ceiling there was a very impressive painting of Christ on a throne with cross in one hand and a Bible in the other. On his head was a crown. We also saw paintings of saints and of the resurrected Christ.

We had the opportunity to talk to a thirteen-year-old Russian boy. His mother worked in the church and we were particularly interested in finding out if he believed in God and accepted the teachings of his church. Our guide had done his best to convince us that only old people went to church in Russia and believed in God. We had in the same church heard from the sexton that students from Moscow University sometimes attended religious services out of curiosity.

I asked the youth, "How often do you come to church?" He answered, "Every day. My mother works here." When I asked him, if he believed in Jesus Christ, he answered, "Yes." It was quite evident to us that the boy had received some religious instruction at home. During the short interview our guide, Alexis, seemed quite ill at ease. He had insisted on interpreting while we were talking to the sexton. In several instances he attempted to put into his own words what the sexton had said and thus to distort the latter's words. This was obviously an attempt on his part to minimize religion's inroads in Russia.

It has often been asserted by the Marxists that religion is an opiate of the people and that with the passing of time it will die out. I found that most of the young people whom we met did not believe in God. Among these young people were several who were opposed to the regime. We did, however, meet many elderly and middle-aged people who were staunch believers and church-goers. We met some of these people at the monastery at Zagorsk, a town about one hour's ride from Moscow. The monastery was founded 600 years ago by St. Sergius. It is located behind high, medieval walls and consists of eleven cathedrals which date from 1422. The Godunov family is buried there and Patriarch Alexis has his summer home in the area.

We were given a guided tour of the monastery and after the priest had left us, we were free for several hours to roam about on our own. We noticed a number of people, some of them young people who were worshipping, chanting, and kissing relics. In front of the church several Russian people surrounded us upon finding out we were from the United States and asked us many questions. Of these questions at least two pertained to religion. They wanted to know if we were believers and if young people went to church in America. When I answered these two questions in the affirmative, the people around me literally became joyous. Some of us had pictures of churches in America to show. This elated the crowd very much. In fact one of the girls from Minnesota showed an elderly lady a picture post card of an Orthodox church in Minnesota. Upon seeing this picture she began to kiss Eleanor on the arms.

From the personal contacts that we had with both people and churches I believe it is safe to say that religion still lives in the Soviet Union. The regime has attempted to indoctrinate the young people in Marxism-Leninism, it has printed scores of anti-religious books and pamphlets, and it has encouraged harassing and ridiculing of young people who do believe in God. An example was related to us of a young Russian boy who wanted to study for the priesthood and who was tormented and harassed by both his classmates and teachers. He made up his mind, however, to be a priest and entered a seminary. From very reliable sources we learned that it is forbidden for soldiers in the Soviet army to wear crosses.

One evening at a carnival in Leningrad I had an excellent opportunity to talk to several young Soviet students about religion and politics. During our conversation I mentioned that I believed in God and that I went to church. Three or four girls with whom I was talking immediately began to laugh and proceeded to ridicule me and my beliefs. One asked me in jest, "Where is God? Is He up there?", pointing to the sky. When I showed my dislike of their anti-religious attitudes, they became apologetic. However, I realized that these young Russians were as sincere in their beliefs as I was in mine. What I found most challenging during my short visit in the Soviet Union was attempting to explain my personal ideas of God, religion, and the universe. Invariably the people to whom I would be talking would look at me oddly as if to say, "How can he believe this?" It was then apparent to me that the Soviet state had achieved partial success in inculcating atheism in the minds of youth.

Not far from the Hotel Astoria in Leningrad there is a magnificent cathedral which is now a museum. It is a large dome-shaped structure with marble columns and is being repaired. Before the 1917 Revolution it was a leading place of worship in Leningrad. Near the top of this impressive building are engraved several inscriptions. One of them reads, "God bless the Tsar." We were astonished to find such heresy plainly visible for all to read. But this was only one of the many paradoxes which we saw while in the Soviet Union. Another one was the golden crosses that crowned the Kremlin cathedrals. These symbols are vestiges of a rich, religious past which the regime has not after forty years been able to eradicate.

In the Soviet Union today it is illegal to sell icons. However, many Russians ignore this ban and apparently do a thriving business on the black market. While we were in the Crimea near the town of Yalta we met a Russian boy who was willing to give us an icon in exchange for some American clothes. Two of us went from our camp to Yalta in order to pick it up. We went to the young man's home where he brought out an icon of Christ. Although it seemed rather old it was in good condition. We gave him the clothes in exchange, and on the way back to our camp we carefully concealed the icon, since it would have been dangerous to carry it observed.

Outside of one of the numerous churches in Kiev I bought a small painting of Christ which was framed and enclosed in glass. An old man sold it to me for the equivalent of one dollar. Since this picture was a copy of an icon, it evidently was safe to sell it in public. In the same church we watched a crowded service. As usual the chanting was impressive and the priest wore a long, flowing beard. Most of the people in the crowd were women, but I noticed a few younger men. Our guide was with us and some of us heard him remark, "Personally, I prefer a ballet." His attitude throughout the trip was antagonistic to religion. We had the impression, however, that he knew more about the Orthodox church than he cared to reveal.

One of our tours in Kiev was to the famous monastery of caves. There were scores of Soviet citizens there, young and old. Upon purchasing a candle from a priest we descended into the lower levels of the monastery. There enclosed in glass coffins were the remains of medieval monks and holy men. Their mummies were wrapped in elaborate cloth and garments. Only the shriveled hands were visible. I noticed that a number of women, mostly elderly, were kissing the coffins. Several persons, men and women, kissed the saints' pictures over the coffins. The spectacle itself was impressive and definitely left one with the feeling that religious emotions still survived in an anti-religious state.

Before I went to the Soviet Union I often wondered just how much emphasis the Communist regime placed on Russia's rich historical past. The ornate, golden domes of the Orthodox churches and cathedrals in Kiev were proof enough that the Christian religion was far from dormant. Many of Kiev's churches had been damaged during the war. Practically all that we saw had been or were being restored. In one church the remains of Yuri Dolgoruki, the founder of Moscow in 1147, rested in an elaborate roped-off tomb. In Saint Sophia Cathedral the famous eleventh century monarch, Yaroslav the Wise, is buried. His tomb was prominently displayed. Even the Romanov burial places in Moscow and Leningrad attract both Soviet and foreign tourists. From what I observed during our tour of the Soviet Union, Russia's historical past is plainly present in her monuments and churches.

THE AUTHOR, who teaches Russian at Western High School, Washington, D. C., spent six weeks last summer in the Soviet Union as a member of an official exchange delegation, under the auspices of The Council on Student Travel. The places visited included Moscow, Leningrad, The Crimea, and Kiev.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

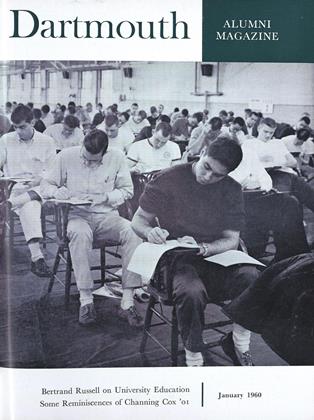

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureDemocracy's Influence on University Education

January 1960 By BERTRAND RUSSELL -

Feature

FeatureA Basic Classical Library

January 1960 By PROF. ROBIN ROBINSON '24 -

Article

ArticleA Famed Collection and How It Grew

January 1960 By EVELYN STEFANSSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

January 1960 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY