(not altogether organized or well thought out) (whoever he is)

MY MOTHER recently called me from Virginia to tell me she had been up in my former bedroom, rummaging through my boxes of notebooks and strange academic essays, and reading them, too. In one of the boxes, shoved far back beneath my four-poster bed, she had sniffed out a green Dartmouth folder containing a hand-drawn map of Cornish, New Hampshire. The map, sketched on a wrinkled sheet of legal paper, rested behind three yellowing articles dated 1990. They had been clipped from The Fortnightly, the now-defunct weekend magazine of The Dartmouth.

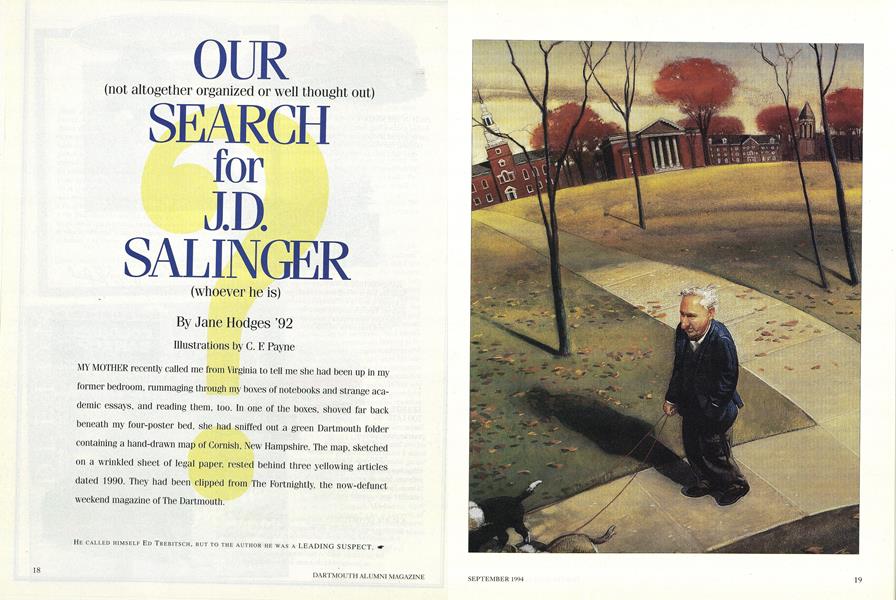

HE CALLED HIMSELF ED TREBITSCH, BUT TO THE AUTHOR HE WAS A LEADING SUSPECT.

"Why Janie," she said to me in the unconscious Atlanta lilt she reserves for expressions of wonder and motherly awe, "I just can't believe all that you've done!"

THE MAP had been a crucial clue in our effort. It represented only a tiny region of New Hampshire, a couple of rivers, bridges, routes, and zip codes all dashed down in a clandestine rush, like a war plan, to define the proximity of Salinger's hermithood to our own gentle cloister m the woods. Tucked inside the hills and dales and Green and White mountains of New England, the homes and gravestones of poets and writers waited for our kind like unbought books on clean Barnes & Noble bookshelves. Few of the artists who arrived at those quiet destinations began their lives in them. A native Manhattanite, Jerome David Salinger was born January 1, 1919, to Sol and Miriam Salinger. His father, a cheese importer, moved the family up in the world by moving them farther downtown, finally settling on the East Side in a building at 91st Street and Park Avenue. Salinger, whose poor academic record during his first year at private school inspired his parents to send him to Valley Forge Military Academy, made his way into campus culture as a sardonic and solitary lampoonist who would later cause great swooning and crushes at Ursinus College, and much great stinking in the literary world.

His first published work appeared in a 1940 issue 01 Story magazine, when Salinger was 21. A decade and many bylines later, The Catcher in the Rye made its way to the great American bookshelf. The novel, published after a ten-year gestation, ushered in the Rebel Without a Cause decade, with its Boy-God Holden Caulfield, heartthrob and cynic, the literary form of James "Don't Call me Chicken" Dean, and the precursor for today's dog-eyed heartpumper Jason Priestley or Dartmouth's new snack for young American estrogen, Andrew Billy Shue '89. Two years after the release of Rye, a fan-weary Salinger moved to Cornish.

The first year saw a still-sociable Salinger entertaining local teens in his home, reading Eastern philosophy, and courting Claire Douglas, the woman he would marry in 1955. Salinger also gave his last public interview that year, an undertaking conducted in innocence by Shirlie Blaney, one of the high schoolers Salinger invited to his home for regular afternoons of chips and soda, music and talk. Ms. Blaney wrote her Salinger story for her school paper only to have some bloodhound over at the Claremont Daily Eagle pick it up as a scoop. After that, Salinger erected a wooden fence around his home. Other than a few painful interviews with snoops and victimizers that amounted to little, Salinger spent the sixties and seventies tightening his circles, battening down his hatches, and acquiescing to Claire's request for a divorce.

New England, and especially the Upper Valley, have long hosted literary refugees who populate the granite hills with varying degrees of flintiness and Yankee spirit. In the Upper Valley alone, a wide cast of characters from all corners of the canon can be found: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn exiled himself to Cavendish, Vermont, until this past summer; Louise Erdrich 76 and husband Michael Dorris lived in Cornish for a decade, and Annie Proulx spent several years working at Dartmouth while readying herself for a world-class literary career. But what made Salinger's presence in the Upper Valley different was the odd way he welcomed his refugee role. After his divorce, after the Shirlie Blaney incident, after the wood- en fence went up around his home, the author became known to those who recognized him as a "very private person" whose very privacy must be kept inviolable. As with a shy child, too much attention made him duck behind his mother's skirts; or, rather, behind the closed doors of his jeep, his home, or the small cabin on his property where he was rumored to write for as many as 16 hours in a day. Over the years he has accumulated mystique, becoming part 800 Radley, part Elvis—part spook, part folk figure. In ignoring the world, Salinger-searching rationale went, Salinger asked for it to come find him. And find him the world did. Reporters have cornered him, students have hallucinated about him, and one novelist, W.P. Kinsella, even fictionalized him as a character in a baseball novel called Shoeless Joe.

Our search was hardly unique. The story has not changed over the decades: Searchers find Salinger, Salinger ignores them, they slink sheepishly away and cough up some copy or some new angle that disguises the fact they have little to report. If our search was different in any way, it had to do with our own personal investments in finding Salinger. I was operating under my peculiar catalogue of curiosities, which involved my knowledge that J.D. Salinger, like myself, was born under the sign of Capricorn, that great constellation of hardship governed by Saturn, the guy who ate his children. I wondered if, perhaps, there was something to the astrology of self-chosen repression, though I did not wonder all that much. My collaborator at The Dartmouth was a plain old foolish optimist, who believed that he could do whatever he wanted, and, because of that belief, often did. Others had taken our approach before and gotten sued for it—such as Ian Hamilton, whose unauthorized biography, In Search ofJ.D. Salinger, used the author's correspondence without the prickly author's permission. Being sued, of course, was not in our plan.

OUR SEARCH began like this: as a quest for a good story idea for The Dartmouth. Our days as student journalists were filled with ego and possibility, assignment and submission, expression and censure. We kept in mind attribution, grammar, deadlines. When we weren't struggling over the clunky AP wire in the corner of the news-room or some desktop-publishing program, we sat on greasy sofas in the office lounge, snacking and tossing about story ideas. It was in this way that I came to know my journalistic collaborator, one Joshua Wesoky '93, whom I found charming and outspoken and, prior to the revealing unfolding of most of his other personality traits, even slightly attractive in a brassy, leonine way.

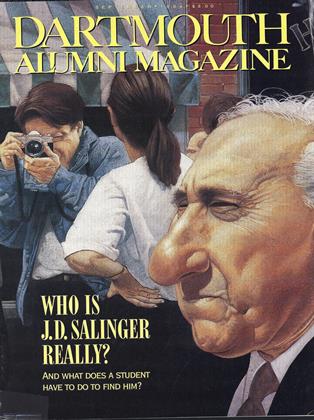

When the idea for the hunt struck us we were tossing stories ideas about, and an old man accompanied by two dogs with gigantic pom-poms around their necks walked by outside the lounge window; he was making his gait into the March wind at a slightly stooped angle. His head was balding down the middle, and his white hair hung in lank Einsteinian tufts that might have been wind-flattened or brilloed-down. He wore a short, lined jacket. He seemed to be in his seventies, and, both hands in his pockets, he looked like he might live alone, reclusively, in the woods or maybe on some Huck Finn-like river somewhere. He rounded the corner, heading for the Collis Center.

"That's J.D. Salinger!" someone shouted in my ear.

"Yeah, he asked me the time yesterday and smiled at me," someone else said, lying.

"The thing is, he won't talk to students," someone else said, inaccurately.

In a rare act of assertiveness I staked my claim: "I'll talk to him. I'll write a story about him! I've done some reading on this," I added, breaking some Girl Scout vow of honesty I had never taken.

"I'll write it with you!" Josh said, tousling his fashionably cut hair about his forehead with a sassy flip of the hand. "I've seen that man around—he shops at the book- store, and he eats at Collis!"

And so the deal was sealed.

The editor of The Fortnightly, Kara Skruck '91, stood up like a struck lightning rod. "You guys," she said. "This is going to be great. It's going to be great. When can I have it? When do you think you can get it in? Do you know one another? Let's have lunch."

And so we all did.

FINDING SALINGER, or confronting his authorial aura, was the first attempt I had ever made at making personal contact with a great writer living in New England. Thinking back on it now, though, getting authors to answer questions about their own writing was no special deal. Two years after the Salinger search, I interviewed Jamaica Kincaid face to face in her rambling Vermont home. I sat in her bright wood-paneled office from which she had transported herself and her readers to a lush Antigua of pain and memory, and I asked her cerebral questions about mother-daughter relationships in her novels. But the interview did not become the revealing communion I had longed for, an event in which the muse of Jamaica Kincaid would come dancing out before me like a ballerina twirling in an opened music box. Instead, there was only Ms. Kincaid, a hospitable and gracious woman with a formidable imagination and a large vocabulary to match. We drank tea and ate Oreos from a china platter, and she offered tidbits about growing up in Antigua, her family, the characters who surrounded her in her youth. It was all a kind favor to me, this interview, stately and very enjoyable, and at the end of it, when we had finished the Darjeeling and had dark black bits of demi-masticated cookie stuck in our teeth, she walked me to my car like any other hostess. I told her again how much I enjoyed her fiction, and she told me she liked my wool blazer. She gave me directions to the Manchester Center discount outlets, and before driving home to write about her I bought a lacy bra from the off-price Calvin Klein shop.

I had hoped for something different, though, at the time of the Salinger search, and that hope came down mostly to this: enlightenment about the male psyche. It makes perfect sense, looking back on it now, that Jamaica Kincaid, an unwitting representative of female subjectivity, was such an accessible subject, and that Salinger, an enigmatic male artist, or perhaps a cuckoo workaholic, was locked up in a fenced-in house protected by an early warning system with his little fictional friends.

Maybe I liked following these authors because I enjoyed reading their genre: I love a good novel about adolescence, that time of life during which we each discover the neuroses that make us tick, those insecurities for which we'll compensate with what we make of the rest of our lives. Like many others before me, and many others to come, I had relished reading the sarcastic but tortured observations of the original disillusioned preppie, Holden Caulfield Searching for J.D. Salinger put me on rewind to the repressed, departed recesses of my own adolescence, that private torture chamber in which I had lain, like Giles Corey shrinking beneath a mammoth wooden vise at the Salem witch trials, begging for the weight of my adulthood. Only this troubled fifties teen, a fictional character, could exist in that void between the material and mystical worlds.

I bought my first copy of The Catcher in the Rye when I was 12. Some puppy-lover who had broken my heart recommended it during one of the stiff conversations preceding my heartbreak. A morose young Honor Roller in a South of bad dermatologists, I would retreat to my room after school and read Linda Goodman s Love Signs while daydreaming about the heartbreaker, who attended my all-girls school's sibling school, Testosterone Central, and who, at that very moment, was probably not thinking about me at all. From him I first heard the book title. "So," my beloved soprano squeaked. "Have you read TheCatcher in the Rye yet?" I blushed on my end of the phone and closed the closet door all the way. "N-n-no," I reverently whispered, vowing to memorize it. The boy hung up and dumped me for a future debutante. But the book, I knew, would make me think of Us, of the Good Times—sweating buckets to J. Geils Band songs, drinking Dixie cups of flat Pepsi, peering tensely at our watches. It promised to provide a coded literary clue about how I had gone wrong in understanding the mythic creature of The Male and been left forever standing in his sneakered wake, beneath the blinding glare of a revolving disco ball, hiccoughing that last swill of Pepsi in unladylike disdain.

Of course, I did not tell my partner at The Dartmouth, Josh Wesoky, all that. He said he had read Catcher three times on various assignments from teachers in sixth, eighth, and tenth grades. I did not know what deeper meaning the book had for him, and he did not tell me.

We began our search shortly after lunch. We positioned ourselves behind pillars on the Hanover Inn verandah to watch old men walk by, hoping perhaps to spot the man with the pom-pommed dogs. On any given day in Hanover a Salinger-hunter might encounter a wide variety of older folks, all of them conceivably Salinger's age. Many of these sexagenerians, septuagenarians, and octogenarians sat for a spell on the Inn porch, or shopped for College souvenirs along Main Street. One of them might have even been J.D. Salinger himself. Josh took photo after photo of these men, clandestinely, and now and then Id stand in front of him, a fake subject in a real photo shoot.

AND SO our search began. I delegated the research to myself, haunting Baker Library s stacks. Meanwhile, my collaborator spread the word that we were writing the article, that it would soon be in print, and that Salinger was going to talk to us. We went to the Dartmouth Bookstore and sidled up to various employees, each of whom spoke to us off the record, telling us in utmost confidence that the mysterious man did occasionally pass through. And what did he look like—his facial features, physical condition, any hair? What kinds of books did he buy? we asked. They refused to tell us. There s sort of an unwritten rule that nobody ever points him out to anybody," John Wing, the bookstore's information assistant, told us. "We have a relationship that's good as it is...he's a very private person, you know." One employee told us on the sly that J. D. Salinger was a weekly shopper. Another told us, "He comes in occasionally basically during the day."

Josh and I walked behind the fiction racks to conspire. "Are you writing that down?" "I thought you were writing that down." "Oh right, make the woman do everything while you do all the talking. I took the pictures. He was right about that, so we went back to the interviews, and I made a note of everything we were told.

We proceeded to Baker Library, where Salinger is rumored to borrow books. The woman in Special Collections told us she had no file on J.D. Salinger's works, whereabouts, or hermithood. She leaned over the counter and looked deep into my pupils and said. He s a very private person, you know. Margaret Otto, the head librarian, and Sue Marcoulier, the circulation desk supervisor, declined to comment on Salinger's patronage. ' I haven't seen him in years," Ms. Otto said.

We retired to the '02 Room tables in frustration. There was nowhere left for us to go but to the source itself. Cornish, New Hampshire. I spread my pile of ancient xeroxed Newsweek stories across the table, and we examined the pictures and captions and descriptions of the Salinger place. One 1960 article described the site as a redwood "five-room house set on 100 acres...so far back in the woods that the mailman has equipped his Volkswagen with special brakes to facilitate travel in the winter snow." Another told us: "The house is remote enough to discourage all but the most persistent idol-hunters."

THE NEXT day we set off for Cornish, Josh with his camera, I with plenty of Diet Coke. I drove, and we hurtied south at a high speed, making my roommate Mary's Honda shimmy in the April wind. We took the Windsor exit and turned left toward the New Hampshire side of the river, driving into Cornish Flat, a town that sounded like a good approximation of the actual town we were seeking. We pulled in to Powers Country Store and began talking with the folks at the counter and shielding our eyes from all the fluorescent orange hunting stuff. "Is it true that J.D. Salinger lives in Cornish?" Josh asked. The man there confirmed that Salinger did indeed live in Cornish but added that he didn't have a box at the post office. His wife seemed less enthusiastic about our search. "I don't know why everyone looks for him," she said, giving us a full once-over. "I could see it if he had been out there publishing books for the past 20 years, but he hasn't been doing that." Then the husband cut in, looking at us with consoling eyes. "He's a very private person, you know," he said.

I was driving along at a good clip, hoping to get back in time for the climactic moments of the lecture on what Freud said about the relationships between Doras laryngitis and oral fixations when Josh suddenly sat up straight and shouted "Stop the car! Stop the car!" I slammed on the brakes and pulled a 180, veering onto the side of the road. Josh had been reading the copy of InSearch of J. D. Salinger we had been carrying around with us for weeks now. He beamed smugly "Well?" I said.

"J. D. Salinger is Polish...and 'Yatsevitch' is a Polish name!"

Aha! I thought. Of course! So...was 'Yatsevitch' some kind of allegorical name constructed to foil spies like us? J. D. Salinger, dressed as a Santa-like Cornish selectman, must have had a good laugh at our expense.

I whipped the steering wheel in the direction of Hanover and swung us back onto the road. "There's only one way to find out if it's him," I said, my nostrils flaring.

"We'll have to check the phone book!" we both shouted as I gunned the engine and slung us north on 1-91.

WE DID find Mr. Yatsevitch in the phone book. But his address was not in Cornish; it was in Cornish Flat. Cornish was where Salinger lived. Cornish Flat wasn't. We decided that we would drive off into the wild with no direction, up all the hills and back-roads overlooking the Connecticut River— which J.D. Salinger can supposedly see from his mountaintop hideaway.

On the way back to campus we locked the keys inside the Beretta while on an important refueling mission at Ben & Jerry's. We called the offices of the D to tell the owner of the car, and she said: "Where are you guys? Everyone's looking for you. Your story is due at five o'clock!" Our mouths fell open. My scoop of Heath Bar Crunch glopped onto the ground. We looked at our watches: It was already quarter past four. "OK," I said, and hung up.

THAT NIGHT, after dislodging the red Beretta door and hightailing it back to Robinson Hall, we wrote a story called "The Hunt for J. D. Salinger." Readers liked it, for we had led them to believe that we were still looking for J.D. Salinger, which we were, sort of, despite our having lost all hope of ever finding his home.

Had it not been for a longstanding appointment with Edward Trebitsch, the owner of the pom-pom dogs, we would have suffered shame at our lack of concrete material. The interview, which took place a few days after "The Hunt" appeared in print, revealed to us an idiosyncratic and crusty Yankee whose story was as interesting as, perhaps more so than, Salinger's. He appeared outside the Collis Center at the arranged time, with his two dogs, 80 (short for "Beauregard") and Mo (short for "Moses') in tow. He knelt down and gave them dog biscuits, told them to stay, and then walked right on into the building. We jumped off the steps and followed him..

I had seen Mr. Trebitsch many times before this meeting, as he had a ritual of parking his car by the Hopkins Center, walking the mutts around the Green several times, then depositing them as he did today at Collis. Inside the student center Mr. Trebitsch would read The Times, sip his coffee, then fold up the paper under his arm and go wandering about the large common room, looking for students of Chaucer and Shakespeare with opened red Riverside Editions in their laps. When he found such a subject, he would sit down with him or her and chat about his favorite story, Troilus and Criseyde.

Mr. Trebitsch made good on his promise by moving to Vermont, into a cabin on the Ompompanoosuc River, where he took up the cause of nudism. Like many others who flourished during the seventies, he also expressed his freedom of the flesh at Union Village Dam, a beautiful pond a mere 20 minutes from Hanover. In his spare time, as a fully clothed civilian, walking his dogs and doing his errands in Hanover, Mr. Trebitsch was known among students as J.D. Salinger. He reminisced for us about the last time someone approached him. The encounter took place outside of Hitchcock dormitory, on a warm

spring evening. Two tall boys approached him, Mr. Trebitsch said, and the chubby one spoke up first.

"Do you mind if I ask you a question? inquired Chubby.

"I do not," Mr. Trebitsch said, in his trademark monosyllables.

"Are you...are you J.D. Salinger?"

"I am not," Mr. Trebitsch said. "But my friends all tell me that J.D. Salinger is the kind of man who would deny that he really is J.D. Salinger."

The boys walked away, looking back at him once or twice and whispering.

After the interview we ran to the offices of The Dartmouth, where I found a handsome black-and-white shot of Mr. Trebitsch naked, up to his knees in river water, a tree branch covering his manhood. The photo had been taken in the seventies. Josh leaned over my shoulder and said, We have to prim that!" And so we did. We called our article, "Ed Trebitsch: Not the Man You Think He Is."

AND THEN, when we thought everything was over and done, things got spicy again. I got a note my Hinman Box from a Dartmouth administrator who had read our stories. "Jane and Joshua I know where Salinger lives,...lf you're interested, we'll talk." We were, and so we visited him in his office. The administrator had lived on the same rural road as Salinger; his children had gotten rides in the author's jeep, and he had been friendly to them—that is, until the day the administrator's daughter, who had reached the age at which one knows what it means to be famous, asked Salinger about his writing. After that, Salinger stopped giving children rides up the hill.

We watched our informant's hands as he sketched Hanover, the Connecticut River, the bridge from Windsor to Cornish, the winding road that veered off from Route 12A, and then...then he ripped the sheet of legal paper from his pad and gave it to us. Now we knew where Salinger lived!

This time we asked Mary to come with us, and we drove straight to the place, stopping only once or twice along the way to take pictures of ourselves at various creeks and covered bridges. The map turned out to be accurate—there it was, the Salinger place, all those acres, all those birches, the subtle hum of what we imagined to be an early warning system buzzing in the air. Josh and I climbed out of the car, and looked all around. We glimpsed the Connecticut, a mountain we decided was Mt. Ascutney, and uphill we saw a blank green field leading to Salinger's side porch, a wooden balcony jutting out from the log-built home. We ran up the hill through the field and snapped a few photos of the balcony, then ran back down the field to the bottom of his driveway. Mary just waited at the bottom of the driveway, the car pointed downhill and idling.

We faced the house.

"You first," said Josh.

"No, you first," I said.

I think we were thinking, for the first time: What did we want from him, anyway? I just wanted to meet him because he was a writer, and because he was there, in that house, and because he didn't want to be met. Josh just wanted to meet him because he was famous, and Josh liked famous people. We heard the rattling of leaves and jumped as a dark bird flew from a branch above us, spreading its wings and lighting into the huge New England sky.

I imagined that at the top of the driveway, not 50 yards from where we stood, a door would open up to some vast and cavernous space, an endless staircase winding its way up to some tip-top chamber where Salinger's entire literary entourage might be sitting in their smoking jackets and dinner clothes looking like some big New Yorker caricature of an Upper East Side family gathering, and that before them would appear the kind of meal I had only had once, as a stroke of luck in France, with lots of Dom Perignon and smoked things in light sauces and glass after glass of perfect wine. After the meal, in Salinger's salon, literary tropes with corporeal bodies would linger indolently, slung on his hassocks and ottomans and chaises and just generally inhabiting his imagination. Then I would be shot for trespassing.

"No, you go ahead," I said to Josh. She honked the horn, and another bird flew out of the tree.

After that, it grew eerily quiet.

When we finished panicking, when we. were done sprinting to the car and yelling "Go!", and had roared away across the two covered bridges, through Windsor, and up 1-91 to the College, we wrote our last episode for The Fortnightly. We quoted everyone but our subject, and we called the story, only partly disingenuously, "The Search for J.D. Salinger Continues..."

FOUR YEARS later, my mother is pulling this map and the three articles from their box, which lies near my sixth-grade diary, a gigantic canister of old letters, and a handful of Disney postcards from the second boy who dumped me. They are in my hometown, in my old bedroom, tucked below the place I used to sleep, in a grass-green folder that has been there long enough to gather a great deal of dust.

She is wondering why I've put these things here, and with that kind of curiosity she opens them. I'm not sure she called to tell me what she'd found beneath my childhood bed, or what it really meant to her, but perhaps it makes her feel the way we felt in seeking Salinger. Like Salinger, these boxes from my childhood have become part of a place's memory, and the memory a part of a certain kind of time.

When Mr. Trebitsch died in 1992, executors of his will discovered he wanted to take Bo and Mo with him, so they could escort him in the next life as they had in the first. The dogs were put to sleep and buried in a plot next to his. If I think about it I can imagine them asleep in their boxes, their pom-poms and forepaws tucked up under their chins, their dreams the rabbit-catching dreams of pups. I imagine them doing what they always did tor the rest of us, making Mr. Trebitsch seem like J.D. Salinger, only elsewhere now. I imagine them coming to life in being remembered by others, standing up and wagging their tails, ready to do the work good characters do, the way I imagine the figure of my mother bent over the little curiosity boxes of my past, calling me up on the phone to find out just who her daughter had been four years ago, or further back in time.

He has accumulated mystique, becoming part Boo Radley, part Elvis—part spook, part folk figure.

One of them might havebeen Salinger himself. Joshtook photoafter photo of thesemen.

And then,when wethoughteverythingwas overand done,things gotspicy again.

Jane Hodges is a writer in New York. Her last story for thismagazine, "Procrastinator's Night," appeared in the Winter1993 issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

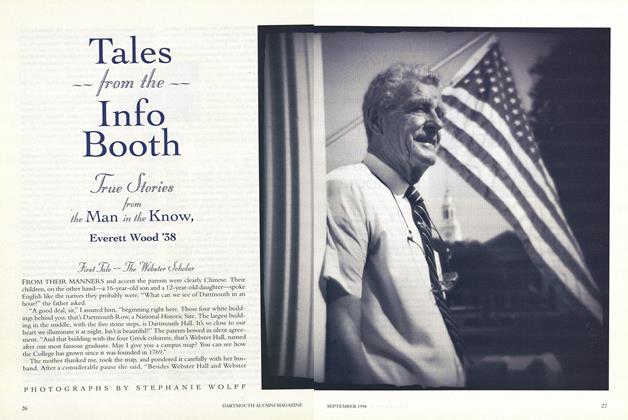

FeatureTales from the Info Booth

September 1994 -

Feature

FeatureThe Run

September 1994 By Stephen Madden -

Article

ArticleSEX AND THE DEVIL

September 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWhat the Soul Asks

September 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

September 1994 By Nihad Farooq -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

September 1994 By Ham Chase

Jane Hodges '92

-

Article

ArticleSeniors Interview Their Elderly Future Selves

MAY 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleWe asked 53 students: "Would You Send Your Child to Dartmouth?"

June 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleGreen Behind The Screen

September 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

Novembr 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

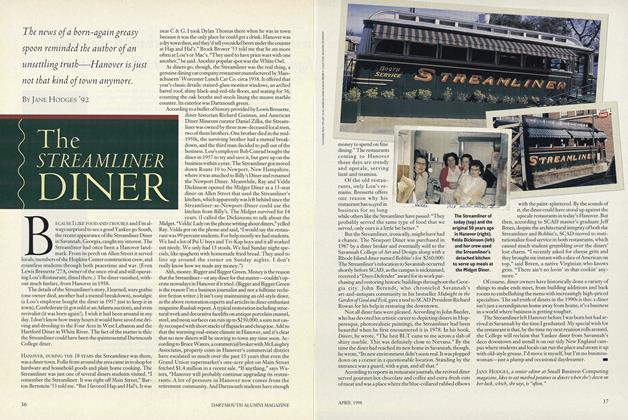

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

APRIL 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureIdea Entrepreneurs

April 2000 By JANE HODGES '92

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryTamara Northern

OCTOBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryArthur E. Allen '32

OCTOBER 1997 By Bill Scherman '34 -

Feature

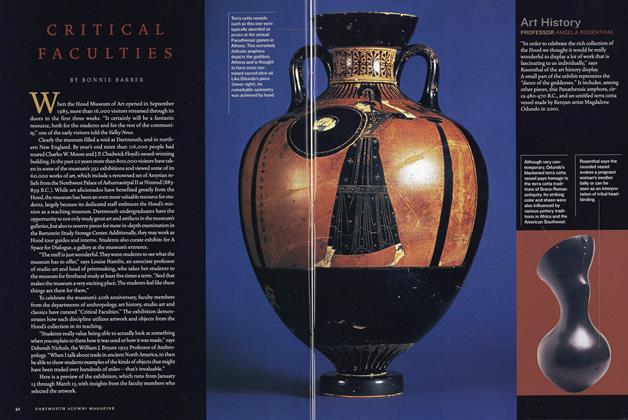

FeatureCritical Faculties

Jan/Feb 2005 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's "New" Curriculum

APRIL 1966 By JOHN HURD '21, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH EMERITUS -

Feature

FeatureWish You Were Here

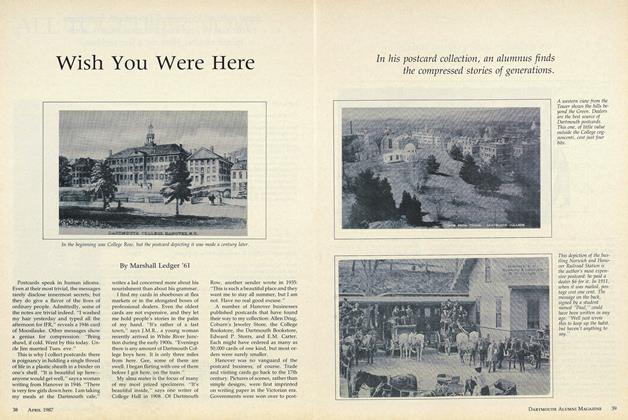

APRIL • 1987 By Marshall Ledger '61