THE warming sun and soft greens of May, softball on the campus, students sunbathing by day and filling the library by night as term-paper deadlines and final exams approached - all added up to a familiar picture of Hanover in late spring. But beneath this calm surface was the nagging fact that Dartmouth College only two weeks before had gone through one of the most disruptive and unprecedented experiences in its history. Appearances to the contrary, the campus this spring was not the same.

Serving 30-day terms in six New Hampshire county jails, for instance, were 29 Dartmouth undergraduates, and ten others were awaiting trial. All had been among the 56 persons arrested by New Hampshire state police for contempt of court when they refused to obey the order of Superior Court Judge Martin F. Loughlin to vacate Parkhurst Hall, which had been seized on the afternoon of May 6 and held for 12 hours until the state troopers broke open the front door and escorted them out, under arrest.

The SDS-led occupation of the administration building took place the day after the Dartmouth faculty, reconsidering an earlier action, had voted to terminate ROTC at the College as soon as possible and not later than 1973. This was not what the anti-ROTC student group wanted. They and some members of the faculty had been agitating for an immediate end to ROTC, asserting that mili- tary units on the campus constituted College support of the Vietnam war and that the moral issue involved superseded any questions of contractual obligations, the rights of students who had elected ROTC, or the wishes of the great majority of the student body as expressed in a referendum conducted on April 28.

The faculty in its January 31 meeting had voted to phase out academic credit for ROTC over a three-year period, but had left the way open for a revised form of ROTC participation. Weeks of denunciation of the faculty decision followed, leading to a non-obstructive sit-in in Parkhurst Hall for three hours on April 22, a demand that ROTC be ended by September 1969, and a threat of "an act of civil disobedience" one week later if this demand were not met. Among the official moves to head off campus disorder, the faculty firmly underlined its commitment to the College policy of protecting freedom of expression and dissent but warning that student disruption of the orderly procedures of the College would not be tolerated and would be subject to disciplinary action.

The executive committee of the faculty voted to get a better fix on undergraduate thinking by means of a binding referendum on whether the ROTC question should be reopened and an advisory ballot on what should be done about ROTC if the question were to be taken up again by the faculty. A remarkable 88.4% of eligible students voted. Reconsideration of the faculty's January 31 action received 1907 "yes" and 599 "no" votes. In the advisory balloting, 2482 votes were cast: 889 or 35.8% for elimination of ROTC after present contract enrollees graduate, 753 or 30% for the faculty's action of January 31, 622 or 25 % for immediate elimination of ROTC, and 218 or 8.8% for retention of ROTC programs as they now stand.

This clear repudiation of the SDS position had no validity in the eyes of the militant anti-ROTC group, and the next day a second sit-in took place in the hallways of Parkhurst Hall, breaking up before midnight when the College surprised the sitters by allowing them to stay on. Two faculty meetings in the wake of the referendum resulted in the May 5 vote (131-60) to set 1973 as the terminal date for ROTC. This was at once denounced by SDS and its followers as "intolerable" and a meeting to discuss tactics was called for the afternoon of May 6. The threat of militant action on May 7 had been issued some days before, but under the exhortation of its leaders the anti-ROTC group moved to occupy Parkhurst Hall at once. It was 3 p.m. and less than 100 persons were initially involved. All personnel in the building were ordered to leave - President Dickey left on his own but Dean Seymour and Dean Dickerson were forced out - and the heavy oaken front doors were nailed shut.

The main objective of this drastic action, entailing a strong possibility of police intervention, was to create a situation and an issue that would polarize the campus and elicit widespread support for the anti-ROTC group. In this calculation the seizure of the building was a dud. The number inside fluctuated between 90 and 65 (the backdoor was guarded but not barricaded) and 200 to 300 with varying degrees of militancy milled around in front of the building. Hundreds more were there on the periphery as onlookers, but approval, much less support, of what the militants had done was markedly lacking.

The Injunction

At an April 26 FOCUS, sponsored by the Senior Symposia, President Dickey had warned that the campus was not a sanctuary from civil law and had advised students not to deceive themselves into thinking they could hide behind the administration or the faculty as to whether public authorities were brought to Dartmouth. "That responsibility starts with you," he asserted.

On other occasions in recent months he had described it as incredible that students, and some faculty, at Dartmouth and elsewhere could be so naive and unrealistic as to think that "anything goes" in trying to achieve their ends or that being on a college campus provides some sort of immunity from the laws that govern society at large, or some sort of special amnesty after those laws have been knowingly flouted.

In the face of previous threats of "civil disobedience" by the anti-ROTC group, College officers had consulted with state officials about procedures that might be put into effect if any campus situation made them necessary. Shortly after the seizure of Parkhurst Hall, petition for a court injunction went off to Superior Court Judge Martin F. Loughlin in Woodsville, N. H. About 8 p.m., five hours after the takeover of Parkhurst Hall, Grafton County Sheriff Herbert W. Ash read the injunction over a bullhorn and gave those inside one hour to vacate the building. At 9 p.m. he repeated the warning and extended the grace period to 10:45. The number of persons inside dwindled somewhat but most determined to ignore the court order, come what may.

Governor Peterson of New Hampshire meanwhile had come to Hanover to confer with President Dickey and other officials. When it became clear that the injunction would not be obeyed, Judge Loughlin ordered the sheriff to remove the occupants and make the necessary arrests. Governor Peterson went to the Lebanon Armory to address the state troopers assembled there and urged them to carry out the court order with restraint. A little after 3 a.m., with a detachment of Vermont state police providing reserve support, the New Hampshire troopers forced open the front doors of Parkhurst Hall and without the use of clubs or weapons brought the occupants out one by one. They encountered virtually no resistance.

The group arrested included 40 undergraduates, two faculty members, two staff employees, and twelve others. Among them were five women and two juveniles, later released in the custody of their parents. Taken first to the Lebanon Armory in two National Guard buses, those arrested were transferred to the Grafton County Jail in North Haverhill later in the morning and then released on $200 bail each.

Judge Loughlin heard the cases in the Woodsville court on May 9. Nine defendants were granted continuances until May 19 since they had not obtained legal counsel until that morning. For the other 45 charged with contempt of court Judge Loughlin handed down sentences of 30 days in jail and fines of $100 each.

Court Appeals Denied

For two weeks following the May 9 sentencing of those arrested for contempt of court, defense attorneys William Baker and Ridler W. Page '60, of Lebanon, made a series of appeals for either bail or habeas corpus that finally carried all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court. Out of these legal moves came a U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals order for new trials for five students who claimed they had not been in Parkhurst Hall, but in the cases of the other forty arrested persons the appeals were denied all along the judicial line.

Defense attorneys began with an appeal to the New Hampshire Supreme Court, Chief Justice Frank R. Kenison '29 presiding, for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds that those arrested and sentenced had not been given sufficient time in which to prepare a defense. This was denied on May 10. The next day, Judge Hugh Bownes of the U. S. District Court in Concord, N. H., denied a similar petition. Defense attorneys then turned to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, Boston, for the granting of bail pending a petition for habeas corpus before that court. Sitting at Wentworth-by- the-Sea, N. H., on May 13, the three- judge Circuit Court denied immediate bail but set May 16 for hearing the habeas corpus petition in Boston. At that hearing the Court released on bail the five students who claimed they had not been in Parkhurst Hall in defiance of Judge Loughlin's injunction, and took under advisement the habeas corpus appeal of behalf of the whole group of 45 represented by attorneys Baker and Page. Five days later, on May 21, the Circuit Court ordered new trials for the five students released on bail, but denied both habeas corpus and bail to the other forty. The New Hampshire District Court, acting on the decision of the Circuit Court, remanded the five cases to the Grafton County Superior Court. On the same day, May 23, Justice William Brennan of the U. S. Supreme Court denied the bail petition which had been filed by the defense attorneys, who had been joined by Boston attorney Allen R. Rosenberg. That made it pointless to try for a writ of certiorari from the Supreme Court since the 30-day jail sentences would be over before the petition could be prepared.

Meanwhile, in the by-now-complicated legal progression, Judge Loughlin of the Grafton County Superior Court had disqualified himself in the cases of five of the nine arrested persons whose trials had been postponed from May 9 to May 19. In the other four cases, he acquitted a student photographer and gave the other three (two of them students) the same sentence he had given earlier: 30 days in jail and $100 fines. Hearings in the five cases in which Judge Loughlin disqualified himself and in the five cases remanded to the Superior Court were scheduled to be held before Judge Richard Dunfey in Plymouth, N. H., on May 26 - and that is where legal matters stood when this was written.

The Aftermath on Campus

With 40 undergraduates jailed, the outer ring of dissidents found themselves with no clear idea of what to do next. A student gathering on the campus the morning of "the bust'' talked about a strike or some other form of protest, and then decided to meet again that night. Two hundred or more turned up for the evening meeting, at which a main theme was amnesty for the students who had seized Parkhurst Hall. In place of SDS (in nomenclature at least) direction of anti-ROTC activity appeared to be taken over by a May 7 Committee and a socalled Parkhurst Group. The meeting broke up for a march to President Dickey's house, but when he was found not to be at home the crowd moved on to Dean Seymour's house. The Dean finally appeared in pajamas and robe, asked the crowd to go home in consideration for his family, and pointed out that civil penalties for the arrested students were now in the hands of the state court, not of the College.

Despite a negligible turnout of pickets in front of Dartmouth Hall the next day or two, the idea of a student strike was revived at an anti-ROTC meeting on Sunday evening, May 11. Some 50 to 75 engaged in periodic picketing the next day, with no detriment to classes or other College activities, but with such small participation and no campus support, the effort to promote a strike gradually petered out.

An idea put forward at Sunday night's meeting by Morgan L. Allsup '69 was more productive. It was a proposal for an All-College Conference to discuss the questions involved in the Parkhurst Hall seizure and the College's policies regarding ROTC. With the help of several faculty members, Allsup's proposal reached the executive committee of the faculty, which gave its backing to the holding of such a conference on the afternoon of May 14. It was believed that the conference would provide an opportunity not only to answer some of the questions on student minds but also to fill in an information void with facts from those in a position to state them.

The conference, arranged by a student-faculty committee and held in Alumni Gymnasium, attracted more than 1500 persons. On hand to speak and answer questions were President Dickey, seven Trustees headed by board chairman Lloyd D. Brace '25 (others were F. William Andres '29, Thomas W. Braden '40, Harrison F. Dunning '30, Frank L. Harrington '24, Dr. Ralph W. Hunter '31, and Dudley W. Orr '29), College attorney David H. Bradley '58, Prof. Fred Berthold Jr. '45, Prof. F. David Roberts, and John D. W. Beck '69 as spokesman for the students opposing ROTC. Although two hours of discussion probably did not change many minds, the conference did serve to clarify things and replace misinformation with the facts. That evening a series of smaller meetings, with Trustees and College officers circulating and participating, was held around campus with greater effectiveness.

The College-wide gathering had one other positive effect. It balanced off the continuing protests and demands of the anti-ROTC group, restored the situation to reasoned discussion, and considerable lowered the tension on compus.

College Disciplinary Action

In the wake of the arrest and jailing of the group who occupied Parkhurst Hall, the question of what sort of disciplinary action would be taken by the College, as apart from the Court's action, quickly came to the fore in campus talk Discipline by the College is in the hands of the College Committee on Standing and Conduct, made up of four faculty members, four undergraduates, and two deans. Publicly expressed views as to what the Committee should do ranged from "kick 'em all out" to the full amnesty advocated by the anti-ROTC group. The latter group asserted that any penalties meted out by CCSC would constitute double jeopardy, since the Superior Court had already passed out stiff sentences.

CCSC refuted the double jeopardy argument, pointing out that violation of Judge Loughlin's court injunction was one thing and violation of the clearly stated College Policy on Freedom of Expression and Dissent was another. It announced that it would take up the cases of all 40 students arrested, as well as those of other students known to be involved in the Parkhurst Hall seizure; that it would hear each case individually with "due process" afforded, and that it would wait until the jailed students were released so each man could appear in his own defense. Its stance was spelled out clearly in a statement it released on May 12:

No member of the CCSC has any doubt that a most serious violation of the College Policy on Freedom of Expression and Dissent took place on May 6th when Parkhurst Hall was forcibly occupied. The Committee is on record as of January 7, 1969, "that all students are subject to these policies and that suspension or separation are appropriate penalties for future violations."

There are those who maintain that for the College to discipline students now being punished by a state court would constitute "double jeopardy." There are two answers to this argument. First, from a strictly legal point of view, double jeopardy applies only to double punishment by a single jurisdiction. The law is clear that two jurisdictions, each having a legitimate interest in the consequences of some violation of law may independently judge and administer punishment. The two violations, though connected, are separate in substance, and their jurisdiction is also separate, the one being that of the state courts over violation of its orders, and the other the jurisdiction of an administrative body of the College exercising institutional judicial power to enforce College regulations.

Second, if a disruptive action by students quires the College to call in police power restore its normal functions, does the Colleae then forfeit any legitimate power to punish those who have violated its regulations? We say no. If a man steals money from his employers, they are not enjoined from firing simPly because they have turned him over to the state for punishment.

if One of the greatest long-ran dangers of not enforcing regulations in the legitimate interests of this community is that other agencies are all too ready to enforce them for us if we do not. We do not wish to see this campus permanently enjoined.

The occupation of Parkhurst Hall involved a flagrant disregard of the rights of individuals; and as an effort at forcing agreement with certain demands by the use of threat and disruption, it was an equally flagrant disregard of the rights of the majority of this College, and of the democratic process in general. We regard these as very serious violations of the reasonable standards regulating discourse and disagreement embodied in College policy.

The CCSC has received a number of communications recommending amnesty for the individuals charged with these violations. Amnesty is defined as a pardon for an offense that has been established as fact. This state of affairs has not yet been reached. We are at this point unprepared to respond to those who advocate amnesty for individuals who have not yet even been summoned before us on such charges. We do have a choice of penalties which can be given for different degrees of guilt, but these choices are exercised after our own "due process." We are not a policy-making body, but we are clearly aware of the importance of our actions in setting precedents. We shall have the matter of leniency on our minds, but we also have a responsibility to uphold College policy. ...

Charges are being prepared against 40 students identified as participants-in the occupation of Parkhurst Hall. These students will be permitted to continue course work until their cases are heard by the CCSC. However, in the case of seniors, no student will be recommended for his baccalaureate degree before his case has been heard and acted upon. The cases will be reached with dispatch when the individuals charged can be heard. Each case will be heard on its individual merit in accordance with the standard procedures of the Committee.

At this writing, the CCSC had met several times to determine its procedures, but no student had yet been called before it. College Proctor John J. O'Connor meanwhile was preparing the cases against the 40 students arrested and against some others known to have been involved in the seizure of Parkhurst Hall. Alumni familiar with an earlier era when the President or Dean could arbitrarily expel a student, find it hard to understand the disciplinary delay. College regulations today provide for "due process" - indeed, court rulings elsewhere have ordered it - and students on trial have the right to appear before CCSC in their own defense, to have counsel if they wish, and to choose between an open or a closed hearing.

Where ROTC Stands

Six days after a hard-core minority had seized Parkhurst Hall in a last-ditch effort to force their anti-ROTC views on the College, the executive committee of the Dartmouth Board of Trustees voted approval of the faculty resolution calling for termination of ROTC programs at the College by 1973. In authorizing offi- cers of the College to implement the phase-out, the committee directed that the termination be carried out "in such a way as to meet commitments to students presently enrolled." The action of the executive committee will come before the full Board of Trustees this month for final approval, but the committee has already in effect acted for the Board.

The faculty resolution adopted May 5 by better than a 2-to-1 vote was as follows:

(1) The Committee on ROTC Affairs shall make arrangements to terminate existing ROTC programs as soon as possible, with the condition that these arrangements do not prevent students presently enrolled in those programs (including those members of the Class of 1973 who have already received Navy Regular and Army scholarships and have been admitted to the College) from completing their commissioning requirements. The only members of the Class of 1973 admitted to the programs shall be those students specified above. In no case shall ROTC programs on the camp us of Dartmouth College be terminated later than June 1973.

(2) The Committee on ROTC Affairs shall work out details by the end of the current academic year so that each of the military programs now present on the Dartmouth campus shall offer no more than two courses for credit and only one member of each unit shall have faculty status until the termination of the programs as specified above.

(3) The College shall assure through its own counseling service that Dartmouth students have full access to information on their military obligations, their eligibility for other officer recruitment programs, and alternatives to military service.

Prof. Gene M. Lyons, chairman of the Committee on ROTC Affairs, and Associate Provost William P. Davis Jr. went to Washington the week of May 19 to discuss ROTC questions with Defense Department officials and officers of the three services. Out of their talks came agreement that Professors Lyons and Davis would return to Washington later with some specific proposals from the College as to how the resolution voted by the faculty could be carried out.

Action regarding the presence of ROTC units on the Dartmouth campus is by no means limited to the College side. In view of the faculty vote and Trustee approval, Defense Department officials may elect to close out the Dartmouth ROTC units before the June 1973 terminal date.

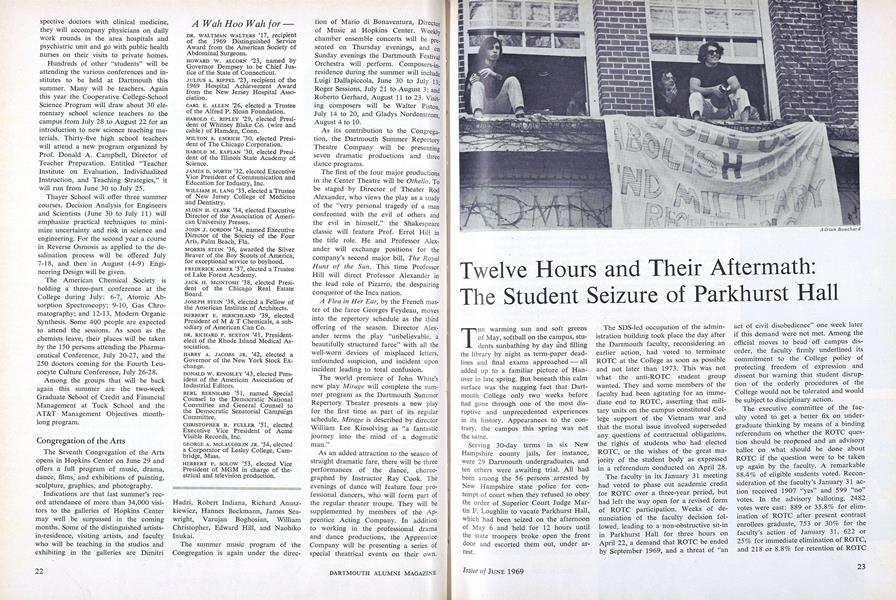

Above, President Dickey argues with astudent occupier outside his office before leaving Parkhurst Hall. Left, DeanThaddeus Seymour, reluctant to leave hisdomain, is forced out by students.

Above, President Dickey argues with astudent occupier outside his office before leaving Parkhurst Hall. Left, DeanThaddeus Seymour, reluctant to leave hisdomain, is forced out by students.

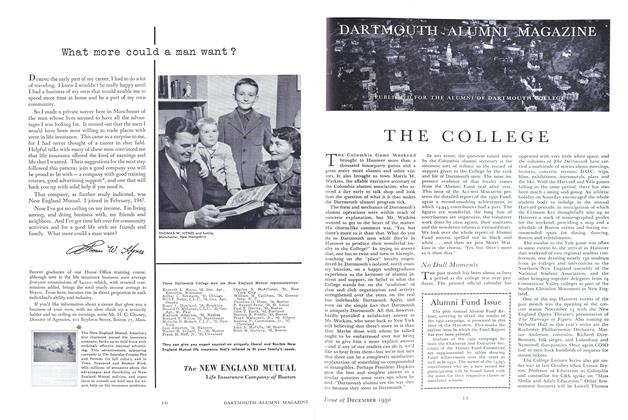

Students blockading Parkhurst's back door.

Sheriff Herbert W. Ash reads the court order by bullhorn to those inside Parkhurst.

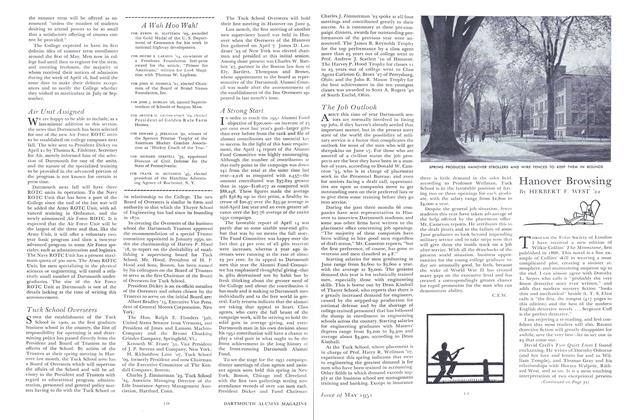

With the court order ignored, state troopers begin to move in to make the arrests.

State troopers bring out a student leader of the building takeover.

Among the Trustees at the All-College Conference were (l to r) Dudley W. Orr '29, Lloyd D. Brace '25, and F. William Andres '29.

Among the Trustees at the All-College Conference were (l to r) Dudley W. Orr '29, Lloyd D. Brace '25, and F. William Andres '29.

Among the Trustees at the All-College Conference were (l to r) Dudley W. Orr '29, Lloyd D. Brace '25, and F. William Andres '29.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

June 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1969 -

Feature

FeatureFOUR PROFESSORS WHO ARE RETIRING

June 1969 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

June 1969 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

June 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1969 By WILLIAM R. MEYER

C.E.W.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureREUNION WEEK

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Faculty

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

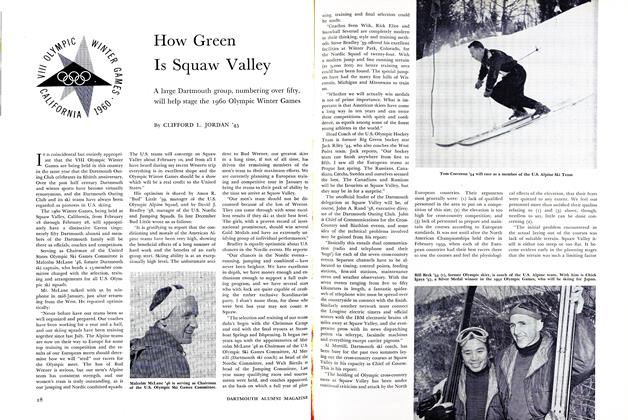

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGetting Things Right

MARCH 1995 By Donald Goss '53 -

Feature

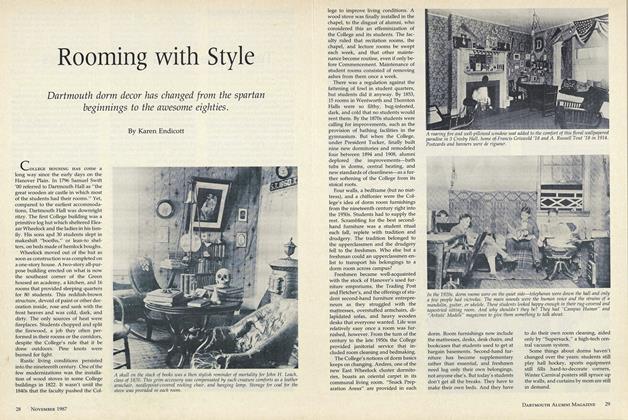

FeatureRooming with Style

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Karen Endicott