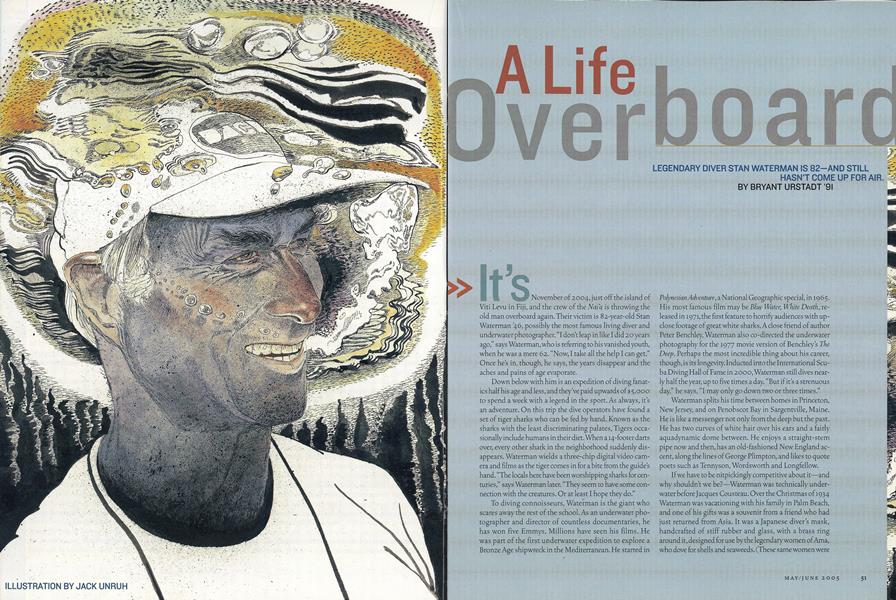

A Life Overboard

Legendary diver Stan Waterman is 82—and still hasn’t come up for air.

May/June 2005 BRYANT URSTADT ’91Legendary diver Stan Waterman is 82—and still hasn’t come up for air.

May/June 2005 BRYANT URSTADT ’91LEGENDARY DIVER STAN WATERMAN IS 82-AND STILL & HASN'T COME UP FOR AIR.

November of 2004, just off the island of Viti Levu in Fiji, and the crew of the Nai'a is throwing the old man overboard again. Their victim is 82-year-old Stan Waterman '46, possibly the most famous living diver and underwater photographer. "I don't leap in like I did 20 years ago," says Waterman, who is referring to his vanished youth, when he was a mere 62. "Now, I take all the help I can get." Once he's in, though, he says, the years disappear and the aches and pains of age evaporate.

Down below with him is an expedition of diving fanatics half his age and less, and they've paid upwards of $5,000 to spend a week with a legend in the sport. As always, it's an adventure. On this trip the dive operators have found a set of tiger sharks who can be fed,by hand. Known as the sharks with the least discriminating palates, Tigers occasionally include humans in their diet. When a 14-footer darts over, every other shark in the neighborhood suddenly disappears. Waterman wields a three-chip digital video camera and films as the tiger comes in for a bite from the guides hand. "The locals here have been worshipping sharks for centuries," says Waterman later. "They seem to have some connection with the creatures. Or at least I hope they do."

To diving connoisseurs, Waterman is the giant who scares away the rest of the school. As an underwater photographer and director of countless documentaries, he has won five Emmys, Millions have seen his films. He was part of the first underwater expedition to explore a; Bronze Age shipwreck in the Mediterranean. He starred in Polynesian Adventure, a National Geographic special, in 1965. His most famous film may be Blue Water, White Death, released in 1971, the first feature to horrify audiences with upclose footage of great white sharks. A close friend of author Peter Benchley, Waterman also the underwater photography for the 1977 movie version of Benchley's TheDeep. Perhaps the most incredible thing about his career, thoughts its longevity. Inducted into the International' Scuba Diving Hall of Fame in 2000, Waterman still dives nearly half the year, up to five times a day. "But if it's a strenuous day," he says, "I may only go down two or three times."

Waterman splits his time between homes in Princeton, New Jersey, and on Penobscot Bay,in Sargentville, Maine. He is like a messenger not only from the deep but the past. He has two curves of white hair over his ears and a fairly aquadynamic dome between. He enjoys a straight-stem pipe now and then, has an old-fashioned New England accent, along the lines of George Plimpton, and likes to quote poets such as Tennyson, Wordsworth and Longfellow.

If we have to be nitpickingly competitive about it—and why shouldn't we be?—Waterman was technically under- water before Jacques Cousteau. Over the Christmas of 1934 Waterman was vacationing with his family in Palm Beach, and one of his gifts was a souvenir from a friend who had just returned from Asia, It was a Japanese diver's mask, handcrafted of stiff rubber and glass, with a brass ring around it, designed for use by the legendary women of Ama, who dove for shells and seaweeds, (These same women were the inspiration, by the way, for the muchunderrated Bond girl Kissy Suzuki, who appeared in You Only Live Twice in 1967.) Waterman donned the mask and swam out along the breakwater off the beach. "I was 11 years old," says Waterman, "and I was hooked. It is still fresh in my memory." Cousteau, that laggard, didn't swim with goggles until two years later, off Toulon in 1936.

Waterman grew up in New Jersey, sum- mering in the same house by the water in Maine. His father was a successful cigar manufacturer and life was comfortable. The second World War only encouraged his diving. He joined the Navy and was stationed by the Panama Canal. In his squadron were a number of Californians who had spent years diving for lobster and abalone. They brought the latest fins and goggles. On leave, they all went spear-fishing together, cruising out to the grounds in motorcycles with sidecars.

During the war his parents died, and Waterman returned to the house in Maine. He went to Dartmouth on the G.I. Bill, majoring in English, focusing on Shakespeare. One of his teachers was Robert Frost, Class of 1896. "He was not a very good teacher," says Waterman. "There was not much interaction or conversation, but we were happy to sit around and let him ramble on." Waterman says he did learn a lot of poetry.

After college he turned to farming blue- berries. There wasn't much else to do with a house in Maine. "It was dull work," says Waterman. Still, there was a lot of water around, and Waterman couldn't help but wonder what lay below. When he heard that Aqua Lungs were available in the United States, he ordered one of the first.

The instructions that came with it just said, "Don't come up too fast," which partly explains why many of the other pioneers in the sport aren't around to reminisce. Relatively cautious, Waterman took it for a test drive in a nearby pond. It was a November day in 1952. Waterman put on a union suit, slithered into a latex dry suit, donned the Aqua Lung and walked like the Swamp Thing into the icy waters of Walker Pond. "I went under and sat on a rock," says Waterman. "There was no visibility, and nothing to see anyway, but it was just as exciting as if I'd seen a white shark." It was the first one in Maine, anyway, as far as Waterman knew, and there was nobody around to teach him how to use it. The setup included a canister of air and breather.

Soon he was diving freelance. He'd recover a mooring or unfoul a propeller for $25. For $125 he threaded cables around a sunken tug so it could be raised. Once he was flown by seaplane to dive into a lake to recover six expensive rifles lost when a canoe capsized.

It was a lot more interesting than blueberry farming, and Waterman dreamed of turning it into a business, running tours, maybe taking customers spearfishing in the Bahamas. In the winter of 1953 he read Cousteaus account of making the first movies 150-feet underwater in the Red Sea and took up the challenge. For that Waterman needed a boat with a wide stern, steady in the waves. Fortunately, he was surrounded by them. He took out a second mortgage on the home in Maine, bought a 40-foot lobster boat, which he dubbed Zingaro, and headed south to Nassau.

and audiences in towns such as Scarlet, Nebraska, would cram churches and town halls to plumb the mysteries of the deep. In one peak year Waterman did 162 dates across the country. He started at $125 per show and after a few years was up to $350 per date. By 1958 the blueberries had withered, and he was diving and filming full time. For three years Waterman led dive tours during the winters, shooting film of his adventures with a 16mm camera in a Plexiglas housing he built himself. He could shoot about a minute and a half before he needed to surface and reload. His first film was called Water World, and he began a lecture tour, showing up in small towns across the country with his films, narrating from onstage. Television was not yet widespread,

He started producing a film a year, with titles such as The Sea People, The Steel Reefs and The Call of the Rising Tide. In the films he clowned around, pretending to get caught reading Skin Diver in the head of a sunken wreck. Narration featured lines such as, "And what of the potato cod, those obese, corpulent clowns?" As television gained viewers, the networks began to buy the documentaries.

In the summer of 1959 Waterman accompanied an archaeological expedition off the city of Bodrum in Turkey, which found a merchant ship from the first century A. D. Amphorae were scattered along the sea floor. The team raised them by flipping them upside down and filling them with air from their breathers. When they surfaced, they shot out of the water like missiles. Later the divers came across the wreck of a ship nearly 3,500 years old and retrieved axe heads, dagger blades and pottery The result was 3,000 Years Under the Sea. An account of the filming appeared in these pages in December 1960.

In 1965 Waterman took his wife, Susy, and children Gordy, Susy-Dell and Gar '78 to Tahiti, where he made a film of the experience. National Geographic sponsoredit it, and the result ran as an hour-long special on PBS, with footage of the teenage Gordy hacking at a coconut with a machetel and paying close attention to dancing lessons given by a Polynesian girl in a grass skirt. "We had a modest kind of celebrity at that time," says Waterman. "I was always thrilled when someone recognized me."

In 1968 he co-directed the first big theater-release documentary feature on sharks, Blue Water, White Death, an adventure described in Peter Mathiessen's BlueMeridian. They worked with white tips off Madagascar, using the first shark cages, custom built for the shoot. The cages worked perfectly but Waterman left them anyway, hoping to get better shots in open water. "The adrenalin was running, and for some reason we thought we could get away with it," says Waterman. "It was very scary." The sharks bumped the swimmers but did not bite. They even bounced off the lenses of the cameras. Audiences went crazy with fear, kicking off the shark mania that continues today.

By then one of the major figures in his field, Waterman began regularly making documentaries for commercial television and was brought on to help film Benchley's The Deep, working with Nick Nolte and Jacqueline Bisset on the wreck of the Rhone n the British Virgin Islands. The Deep appeared to some critics to be a multi-million dollar excuse to film long takes of Bisset in a wet T-shirt, but the underwater scenes are superb and often harrowing. For 10 years in the 1970s and 1980s, Waterman went on to produce episodes of The American Sportsman with Benchley for ABC and ESPN.

When not in New Jersey or Maine, Wa- terman can be hard to find. This year he's slated to accompany dives in Palau, the Cayman Islands, the Galapagos, Indonesia and off the Truk Islands. "I'm slowing down," he says. But he doesn't seem to mean it. On this matter, he likes to quote Tennyson, as he did in a recent interview with Fathoms magazine, saying, "How dull it is to pause, to make an end, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use."

The Life Aquatic Waterman hasbeen on both sidesof the camera—asfilmmaker and star.

To diving connoisseurs, Waterman is the giant who scares As an underwater photographer and director of countless documentaries, he has won five Emmys. of the school.

BRYANT URSTADT wrote about hockey player Shaun Peet '98 in the Jan/Feh 2004 issue of DAM and about DOC director Andy Harvardin Jan/Feb 2005. He also writes for Harpers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

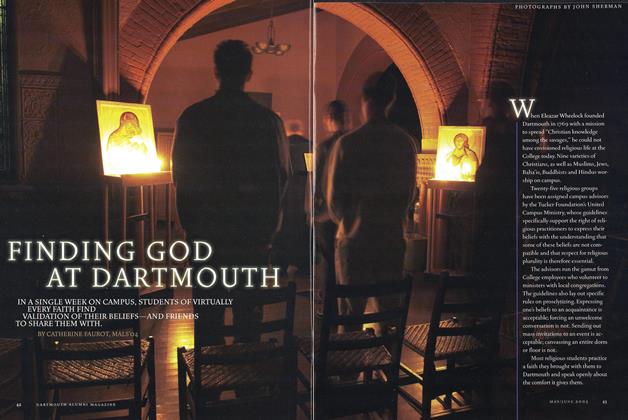

Cover Story

Cover StoryFinding God at Dartmouth

May | June 2005 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’04 -

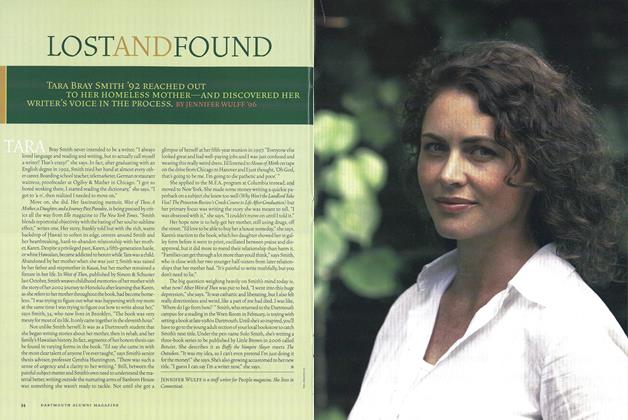

Feature

FeatureLost and Found

May | June 2005 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2005 By Olivia Britt '00 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May | June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR. -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May | June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96

BRYANT URSTADT ’91

-

Feature

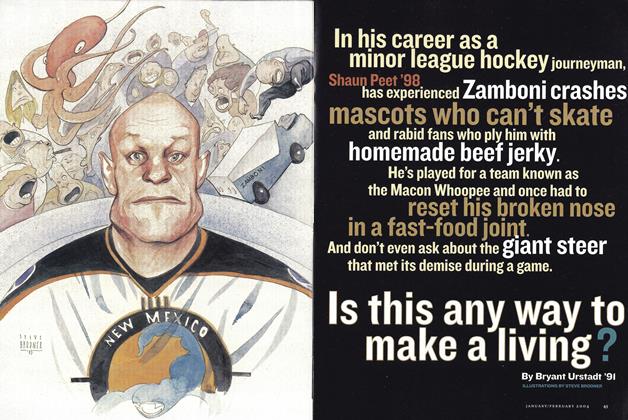

FeatureIs This Any Way to Make a Living?

Jan/Feb 2004 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

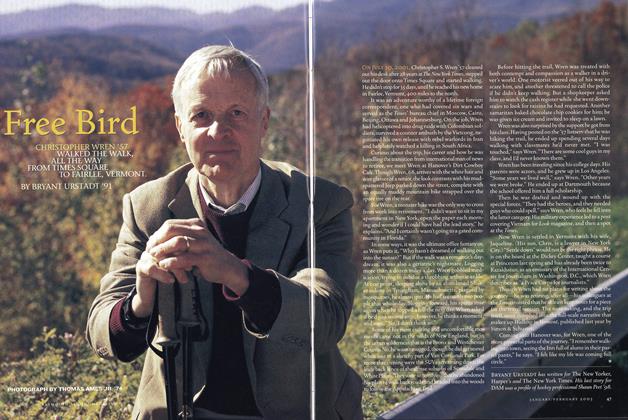

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureCold Warrior

Jan/Feb 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

Nov/Dec 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureOn the Money

Nov/Dec 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for Reunions

JULY 1964 -

Feature

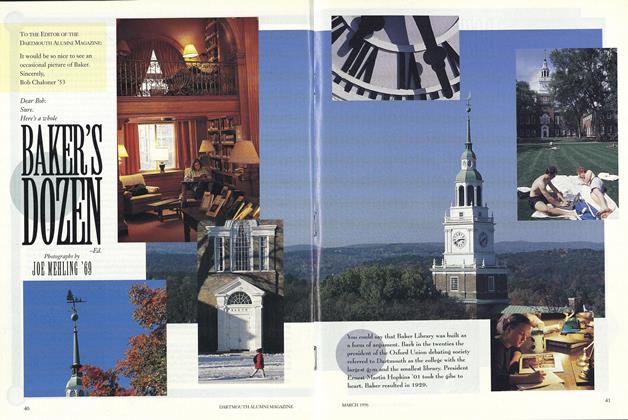

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

APRIL 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

Feature"Innocent Ardor and Delight": A Tribute to Richard Eberhart

SEPTEMBER 1984 By James Melville Cox -

FEATURE

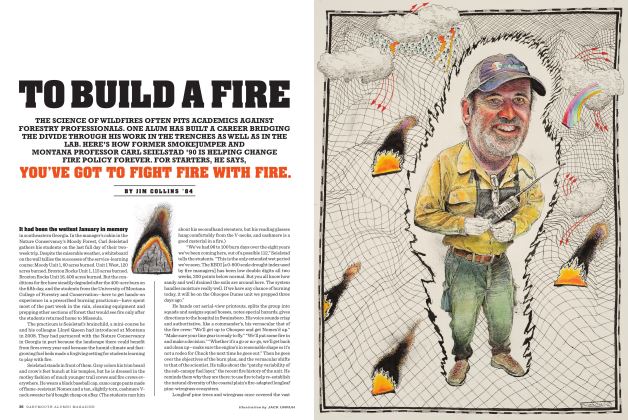

FEATURETo Build a Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

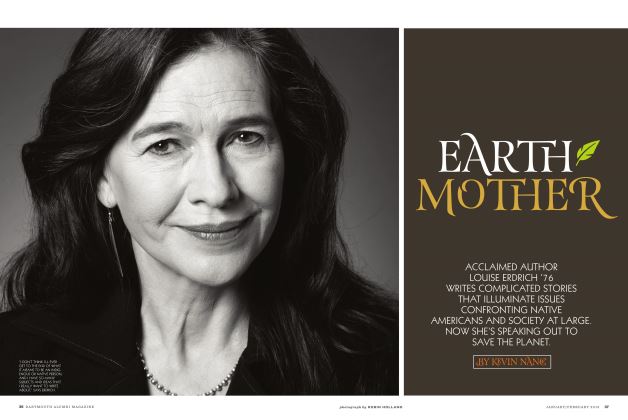

COVER STORY

COVER STORYEarth Mother

JAnuAry | FebruAry By KEVIN NANCE