THE SENIORS' VALEDICTORY

IN a few minutes, several hundred of us will receive Bachelor of Arts degrees, symbolic of a completed college education. Since only one of every ten male adults in this country can claim that particular attainment, the possessor of a college degree is still a marked man, looked upon with respect, and perhaps even with fear, by those who lack this higher education. It is still true that knowledge is power. The educated man bears a peculiar image, an aura of accomplishment compounded perhaps by arrogance, as those New England neighbors whom we have often blithely dismissed as "emmets" might tell us.

The image of the educated man is both more pervasive and more sharply defined than we might wish. We bear it ourselves as a mirror of our aspirations. Yet we, most of all, realize that the image is in large measure pretense. The surprise of the nation at the recent television scandals stemmed in large part, it seems to me, from the fact that particularly well educated men were involved.

But since each of us in the graduating class today takes a long step forward toward assuming this image, it behooves us to examine some of its characteristics. Three which seem worthy of examination this morning concern the nature of the educated choice, the breadth of educated tolerance, and the depth of community initiative expected of the educated man.

First, the educated man is imagined as one whose choices are a bit more conscious and a bit more rational by virtue of his education. He is pictured as aware of the impact of personal decision. If not a Prometheus keenly alert to his role in history, the educated man is at least supposed to know that there is a history, that he is in it, and that if he takes the proper action at the proper time, he might affect its course. Plainly put, this means that we are supposed to know what we. are doing. If one of us is going into medicine, for instance, he is thought to have clear and noble purposes set before him in adopting that profession.

In our four years of comparative solitude at Dartmouth, we have had ample opportunity to learn to use our reason, and to gain a knowledge of various moral criteria, so that we may understand the implications of decision. We have made important choices ourselves, yet the choices we have made thus far, many times, have been divorced from a context wherein our choice would have an appreciable and irrevocable effect upon our lives. The decision to go to Boston for the weekend, at the risk of writing a poor blue book on Monday morning, does not have the smack of finality found in the decision to embark upon a lifetime career. Choice in a responsible context has a peculiar bittersweet quality.

A second characteristic of the image of the educated man, it seems to me, is the expectation that an exposure to the varieties of human experience has brought an increased tolerance of other ways of doing things. Put plainly, this means that we are supposed to understand that there is no single easy answer. Whether through studying the vagaries of European history, the ambiguities of modern physics, or the varieties of English literature, we have encountered diversity. From this diversity, we may learn to have an open mind.

This is an expectation many of us may find it increasingly difficult to meet. Paradoxically, choice and decision imply exclusion, and often intolerance. If we choose to be Republicans, the value of commitment ends when we begin to hate all the Democrats. The capitalist has gotten himself into a narrow corner when he is unwilling to admit that there is any validity at all in the socialist approach. I suggest that it is worse to believe totally, blindly and with bias, than to maintain a reservoir of doubt.

A contemporary philosopher, Charles Frankel, has pointed out that although we do possess an idea of perfection, there is no such thing as a perfect idea. Yet those who would peddle the perfect idea are all about us. As increased knowledge makes us more aware of the immensity of the knowledge we lack, it is easy to be captured by the single easy answer, the perfect idea, the ready-made system.

We may, if that is our choice, leave the tools of thought behind us this morning, as well as the willingness to form judgments on the basis of more than a knowledge of who is on which side. Perhaps we never really had that habit in the first place. But I suggest that if we leave Dartmouth with only a degree, a job offer, and a five-year subscription to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, we may find that our capacity to care turns sour, and becomes instead the capacity to despise.

And finally, a third characteristic of the image which we acquire by virtue of our education is an air of authority in our public action. While a few extreme partisans of democracy might insist that men are equal even in their capacity for public leadership, most would admit that education does in fact better a man's capacity for achievement in the common interest. The same air of authority, that of power from knowledge, also betters a man's capacity to thwart that common interest.

Obviously, a majority of us will not enter public life as a fulltime pursuit, but the variety of opportunity is great, ranging from a positive attitude during a period of service in the armed forces, to service on a local school board, to the designing of a beautiful public building. Educated men have a unique dominion in the public realm. If it is unexercised, they can have little complaint. In fact, it is difficult if not hypocritical in a democratic nation to be an observant, critical citizen if one is not willing to partake, in even a small way, in the task of bettering our common government. The, .opportunities to make significant choices and to preserve tolerant attitudes are best maintained in a free society, which is neither the same as a free nation nor a phenomenon one generation can guarantee to the next. Abdication of community and national leadership is surely one of the most serious betrayals of the image of the educated man.

Certainly, this is not an exhaustive discussion of the characteristics attributed to or attributable to the educated man. We may also be viewed, both by others and by ourselves, as technically capable and materially prosperous because of our education. We cannot exclude the connotation of aloofness from the image of the man educated in the Ivy League.

Few could doubt today that we have sufficient opportunity to exercise the capacities for conscious decision, the inclination toward tolerance, and the talent for common leadership that we do possess. It takes the greatest sort of national tolerance to put up with insults from Cuba as well as the Soviet bloc. To change a society which still rewards nightclub proprietors more handsomely than teachers will require exemplary leadership.

For two-thirds of us, today marks the end of only a portion of our formal education. But for all of us it marks the end of our first taste of the liberal arts. For this beginning, as we say farewell, we thank Dartmouth.

The acceptance of a Bachelor of Arts degree is a major landmark in the assumption of the image of which I have spoken. We, best of all, know that our degree signifies a hope, not a promise. I suggest that to the extent that we turn this hope into a promise, we can fulfill the image of the educated man.

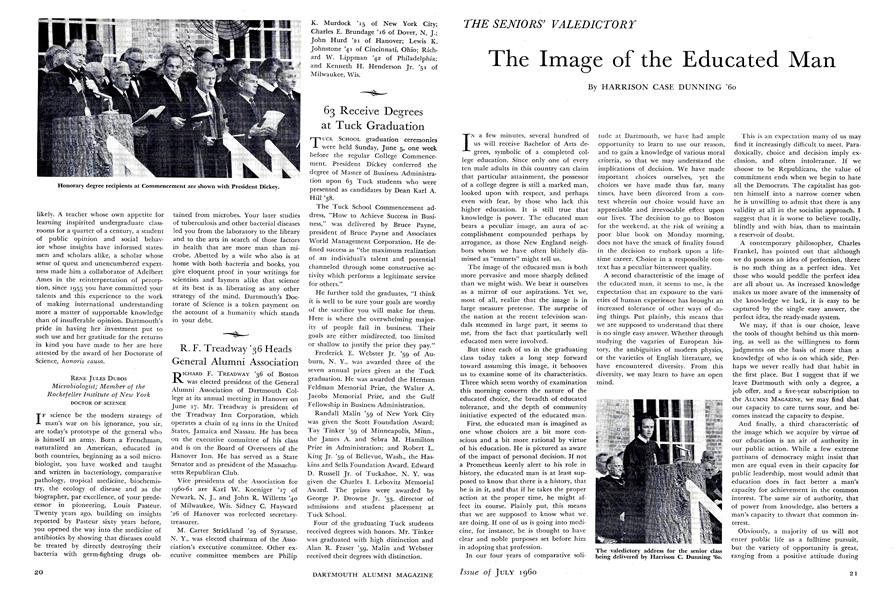

The valedictory address for the senior class being delivered by Harrison C. Dunning '60.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1960 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1960 -

Feature

Feature1960 Commencement

July 1960 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1960 -

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service ...

July 1960

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryTales of Dropouts And Bootouts Who Made Good Anyway.

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S FULFILLING OF THE SCRIPTURE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1972

JULY 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Woes of the Hoit Brothers

November 1968 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureNATIONAL SECURITY: Issues and Prospects

December 1960 By LOUIS MORTON -

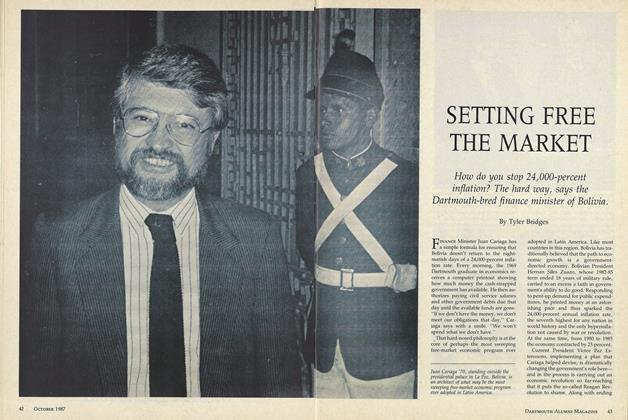

Feature

FeatureSETTING FREE THE MARKET

OCTOBER • 1987 By Tyler Bridges